-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

The making of U. S. bombers

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

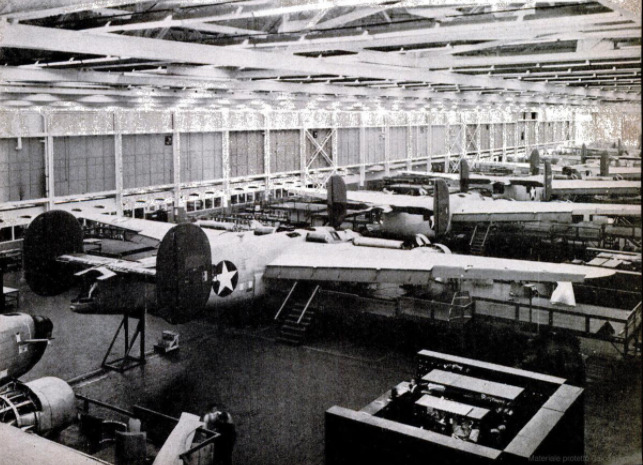

Title: Look out Hitler, here come the flood!

-

Subtitle: Liberator bombers rolling off assembly lines show how mass production will swamp the Axis

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

I HAVE just spent two days trying to ab-

sorb a quick glimpse of a fantastic fu-

ture. My feet hurt from walking so far;

my eyes ache from straining to see so many

complex things; I feel somewhere between

a state of brain fag and bewilderment, from

trying simply to appreciate the immensity

of an act of industrial imagination and faith

so vast that it is beyond the possibility of

quick human comprehension. I have been

visiting the Willow Run bomber plant,

created in the open country of Michigan

by the Ford Motor Company and the Army

Air Forces.

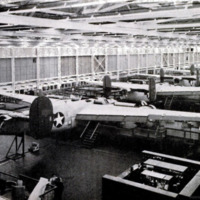

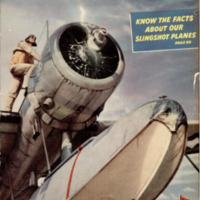

Willow Run is America’s big all-out at-

tempt to apply the technique of automobile

mass production to the rapid manufacture

of a four-engine bomber—the Liberator, the

Consolidated B-24. Less than two years

ago this vast site was a woodlot among the

fields; most of its thousands of workers

were untrained grocery clerks, farm hands,

stenographers, and home girls. Today,

after passing through all the preliminary

acres of fabrication, you come to four long

assembly-line conveyors, which eventually

merge into two closely packed moving rows

of bombing planes on the verge of comple-

tion. These are not just airplanes, mind

you. The long-distance bomber is the most

complex precision machine ever devised by

man.

How often these assembly lines move—

how frequently planes roll out to join their

predecessors on the plant's great flying field

—no one is permitted to say. In any case,

a figure that is true today would be false a

month from now. But it is possible to say

that Willow Run is running. The river is

rising. Mr. Hitler, here comes the flood!

Those thousand-plane bombing raids over

Germany were mere dress rehearsals, All

the books and articles and talk about air

power and bombing the Axis to its knees—

they were mere advance scriptwriting for

this mechanical drama which now begins to

move. Mystery and secrecy and rumors

have surrounded it. There were whispers

from those who said it couldn't be done, and

from those who said it should have been

done faster. True, there have been monu-

mental difficulties and delays. After all,

Rome was not built in a day. But now that

the curtain lifts a little, it is possible to as-

sure Mussolini that Rome could be de-

stroyed in a few hours.

While Hitler's divisions drove through

France, less than three years ago, Presi-

dent Roosevelt called for an increase of air-

plane production capacity to 50,000 planes

a year. Practically everyone thought he

was talking big, taking a random shot at

the moon. Airplane building was then lit-

tle beyond the handicraft stage, for the sim-

ple reason that big orders for big planes

had been practically nonexistent. But then

the aircraft industry proceeded to work

miracles; and today the President's auda-

cious production aim is a reality, almost a

commonplace. The aircraft industry ac-

complished this by speeding up the natural

development of its already tested methods

of production.

To this miracle Willow Run contributed

very little. This plant is something extra,

added on top of all the rest. It is an at-

tempt, starting from scratch, to encompass

the natural industrial evolution of 20 years

all in one big gulp. In place of the air-

plane craftsman’s method of cut, bend, and

fit—by which fighting planes are still pro-

duced—it seeks to sweep in the principle

of interchangeable parts.

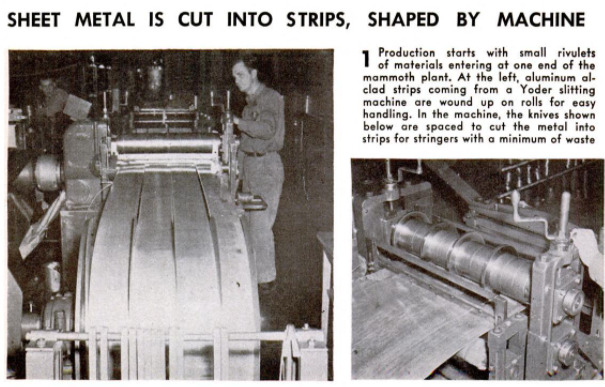

‘Willow Run has been making “parts” for

a long time. This does not sound very im-

pressive, until you discover that in Willow

Run language a “part” may be something

no more simple than a center wing section,

60 feet across—the structural element on

which are assembled the four engines, the

fuselage, the landing gear, and a complex

infinity of hydraulic and electrical controls.

Counting 700,000 rivets, there are 1,250,

000 separate parts in a B-24. You enter the

plant at the manufacturing end, where the

raw sheet duralumin comes in and is cut,

stamped, and molded into these integral

units. As you move on, into the great

acreage devoted to subassemblies, the parts

become more complex. For each part there

is a jig or fixture (the terms seem to be

used * somewhat _ interchangeably, though

most of the Willow Run installations are

properly fixtures) into which the original

parts are fitted and assembled into a precise

pattern. No matter how big or complex, a

“part” thus made will mate precisely with

its adjoining parts, on the assembly line.

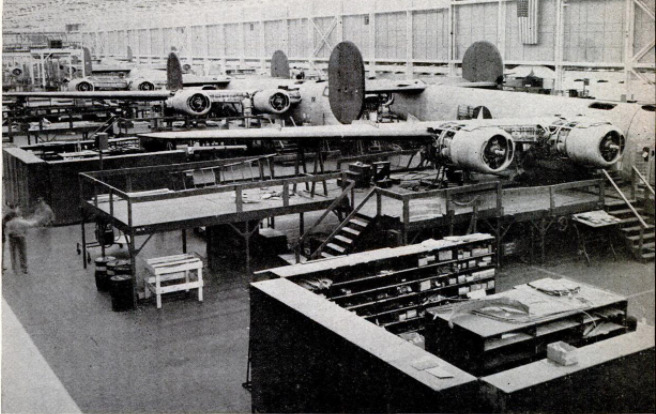

Far down the plant, the final assembly

begins to take shape. The 60-foot center

wing section, in crude form, is placed in a

conveyor system, suspended by its ends.

There is not just one of these conveyors;

there are four of them side by side, each

carrying a row of center wing sections on

from station to station, gaining additional

complexity at each stop. At one such sta-

tion, for instance, the wing section en-

counters an Ingersoll milling machine which

simultaneously carries out on it 26 different

machining operations—doing in less than an

hour a complex lot of metalworking which

formerly took days. That is what happens

at just one station.

At last, after the wing section has ac.

quired its landing wheels, the four conveyor

lines are drawn together into two final as-

sembly lines pulled by underground cables.

This makes room for the planes to take on

their outer wing sections and attain their

full spread of 110 feet.

Elements of mass production have been

introduced in all military-airplane plants.

At Willow Run, planned originally for mass

production, the Ford organization has in-

troduced speed-up changes which fall into

four main categories. They can best be

made clear by taking them up one at a

time.

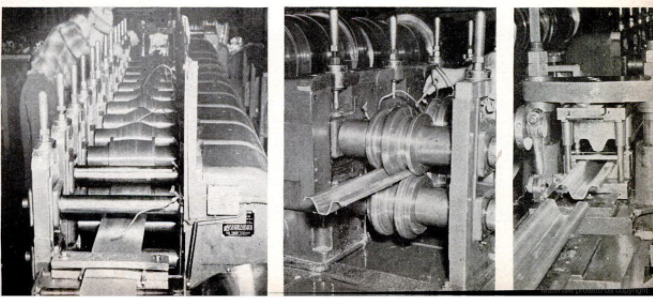

1. The use of great, heavy presses with

hard steel dies, such as are used for stamp-

ing out automobile bodies, for drawing,

bending, cutting, and forming various du-

ralumin parts.

The big Ford presses stamp out parts like

50 many biscuits, but it required great in-

genuity to make this possible. Special

steels had been developed for automobile

stamping, and the special properties of air-

plane metal were quite different. Its cold

flow is such that it tends to wrinkle and

fold; dies had to be devised to allow for

this. There were those who thought it im-

possible, but it has been done.

Outstanding in the press work are the

complicated frameworks for such parts as

the pilot's and bombardier’s transparent en-

closures. A single stamping in one case

now forms a piece formerly made with 33

parts. This was accomplished by using a

softer, thicker grade of metal, which would

draw better. The extra weight was counter-

balanced by elimination of rivets and over-

lapping joints.

2. Better tooling than the airplane indus-

try ever before could afford. In small avia-

tion contracting the tooling cost was always

the most dangerous item. At Willow Run

no expense was spared to get the best tool

for each operation; and the jigs and fixtures

are more accessible and more heavily con-

structed than ever before. For assembling

stringers, for instance, it had been custom-

ary to use loftboards—great tables bearing

full-scale drawings, which made workmen

dependent on ink or pencil marks for their

dimensions. At Willow Run every such op-

eration has its own steel bench or frame-

work, with dimensions unalterably and pre-

cisely fixed in tool steel.

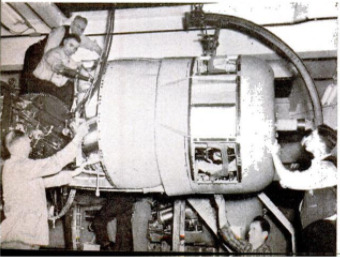

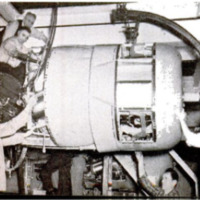

3. The plane is broken down into smaller

parts for subassembly than ever before.

The jigs and fixtures are so constructed

that “detailed installations can be made

long before the final assembly line has

been reached.

When an airplane fuselage is built as a

unit, for instance, its interior is a very

crowded place in Which to work. In the

forward section of a fuselage, a half dozen

workers would find themselves crowded and

interfering with each other. But when that

section is constructed as four separate pan-

els—top, bottom, right, and left, then two

dozen men can work on the interiors of these

panels simultaneously with plenty of room.

4. The final big

factor is that Willow Run, no matter how

Dig, is still only one part of the Ford empire.

When forgings and castings are needed in

a hurry, they can be whipped out quickly,

at the River Rouge plant without any wait-

ing. When special problems arise, specialists,

laboratories, and instruments are available.

Those are the advantages of Willow Run

as it moves in to stack its productive ca-

pacity alongside that of the established air-

craft industry. Its great disadvantage has

been inexperienced manpower. Generally

speaking, it has been necessary to train the

thousands of workers right from the funda-

mentals up. The plant's apprentice school

was started long before the factory was

complete, and employee attendance at school

today exceeds 8,000 student hours a week.

‘The crucial shortage is in experienced pro-

duction men, men Who know how to organ-

ize the sequence of operations and get them

moving. While Willow Run was getting

ready to start, many such men were

snapped up by other plants and other indus-

tries. However, despite rumors and criti-

cisms to the contrary, it can be stated at

this writing that Willow Run is running on

schedule; in quantity and in quality its out-

put is up to the standard set for it in ad-

vance. By its very nature, mass production

takes a long time to get started; but when

it moves, it moves fast!

Up to now, Willow Run's capacity for

making parts far exceeds its final assembly

output. For one thing, the place was origi-

nally projected as a parts plant, for making

subassemblies to be shipped to final plants

in Texas and Oklahoma. Planes are mov-

ing in this way now in great trailers de-

signed for the purpose—vans big enough to

enclose a 60-foot center wing section. Two

of these road freighters, 73 feet over all for

tractor and trailer, carry all but the engines

of one B-24. They are moving monuments

to the way some production planners were

thinking in the days before the rubber and

gasoline shortages.

That way of thinking seems to be on the

way out. The final assembly line is taking

more and more “parts.” The river is high

on the banks of the tributaries upstream.

Farther down it's about time for the flood.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Hickman Powell (Article Writer)

-

Ford Motor Company (Photos)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1943-05

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

78-85,202

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public Domain (Google Digitized)

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Matteo Ridolfi

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Popular Science Monthly, v. 142, n. 5, 1943

Popular Science Monthly, v. 142, n. 5, 1943