-

Titolo

-

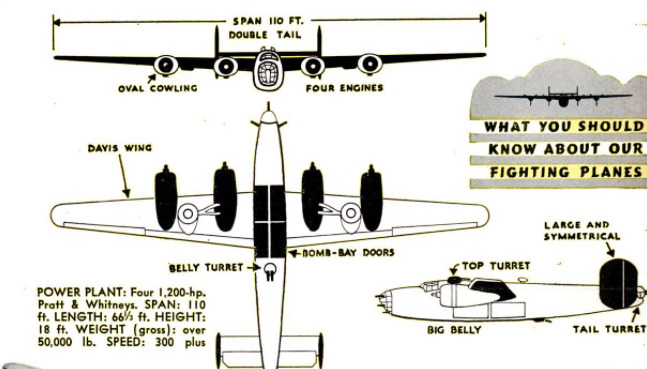

The Consolidated B-24 Bomber "Liberator"

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Title: The Liberator

-

Subtitle: Our Consolidated B-24 bomber carries a promise of deliverance to the world

-

extracted text

-

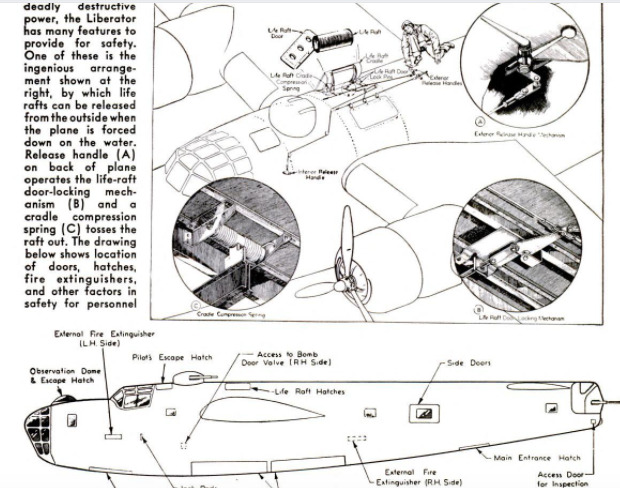

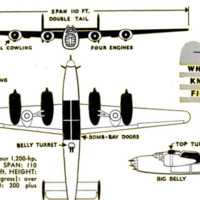

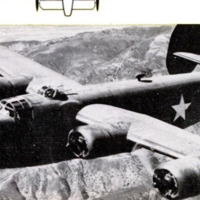

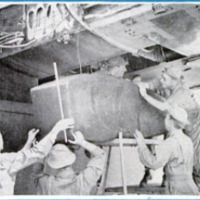

WHEN , Winston Churchill flew from

England to French Morocco for his

historic meeting with President Roosevelt

at Casablanca, he used a Consolidated Lib-

erator—the same plane, with the same .

American pilot, which had carried him to

Moscow for his conference with Stalin. The

fact is significant, for this long-range, high-

altitude precision bomber has come to mean

just what its name implies—a symbol of lib-

eration for the oppressed peoples of Europe

and of all other parts of the world where

the Axis has set its heel.

Who gave the Army’s B-24 her name may

never be known. Two years ago, Major

Reuben Fleet, then president of Consolidated

Aircraft Corporation,

wrote the Navy De-

partment saying that

here was a ship that

‘would liberate the world

from tyranny. Some

time later, an uniden-

tified Britisher dubbed

her “Miss Liberator.”

No one, not even her

makers at the Consoli-

dated plant in Califor-

nia, where she was

born, is proud of her

appearance. She looks

fat and awkward in-

deed, and sits squat on

an airfield, with husky

.50 caliber machine

guns sticking like pin-

feathers from her nose,

belly, back, sides, and tail. But don’t let her

seeming clumsiness fool you. She's one of

the deadliest and most devastating weapons

ever created by the hand of man; with that

quality her builders—and, more important,

the men who fly her—are tremendously sat-

isfied, for she carries a heavier bomb load

than any other ship of her class.

Sitting on a field, the Liberator bids for

confidence. You can't see all the features

that make her a much-feared aerial battle-

ship. She rests on three wheels as the en-

gines bark into action, when she rolls away

with a throaty roar for a 120-m.p.h. take-

off. Turbo-superchargers help carry her to

great heights, and with two engines shot

away she can maneuver normally. She's

more heavily armed than the Flying For-

tress, America’s first

gift to precision day-

light bombing.

The Liberator is as

truly tailor-made as the

finest suit in your

wardrobe. She rolls off

the Consolidated as-

sembly lines ready to

fly. But she can’t go

to the pilots in Libya

or the Aleutians or the

Solomons until her en-

gineer-tailors have

fitted her for the pre-

cise job and conditions

she will face.

If she’s bound for

cold country, shutters

must be installed on

the oil radiators, spe-

cial preservatives applied to the engines,

lighter oils and hydraulic fuels poured into

her tanks. For desert duty, special filters

are installed to keep sand out of her in-

duction and fuel systems. These modifica-

tions are made at several depots, and when

they're completed, the Liberator is ready

for the firing line.

During a brief battle career this four-

engine monster already has proved her dead-

ly efficiency. The British first used her to

stalk submarines. They equipped her with

depth bombs, and in a matter of weeks sank a

large number of German subs in the Bay of

Biscay alone. Almost before the camouflage

dried on her rounded belly, every Englishman

was convinced she was in truth a Liberator.

Improved Liberators began to reach

American battle lines in mid-1942. Almost

overnight, great stories of their hard-hitting

accuracy with bombs of all sizes began

clicking across the cables and radio. Bombs

from Liberators rained on Roumanian oil

fields last June. That was a pasting heard

around the world, for it announced that

Uncle Sam was about ready to tackle Eu-

rope with daylight raids, sending over in-

creasing numbers of precision bombardiers.

Soon the Liberators’ attacks increased in

both the Far and the Near East.

You'll have to skip around the map a bit

to follow their trail of destruction. Libera-

tors helped punish the Japs at Attu, Agattu,

and Kiska, stemming a northern advance

that might have doomed Alaska and threat-

ened the American mainland. Working

with Lockheed P-38 Lightnings, the Lib-

erators made sweep after sweep over Kis-

ka, sinking Japanese transports, destroyers,

and cruisers; wrecking important military

installations; kindling large fires and spread-

ing terror among the little brown enemy.

Punching holes in enemy installations and

ships from six miles up became common-

place.

Meanwhile, American airmen riding high

in Liberators swooped across Libya and be-

gan slugging Axis shipping in Suda Bay,

Crete. Other squadrons started dogging

Rommel, unloading hot cargoes on Tobruk,

strafing shipping with their bombs and ma-

chine guns, and making deadly passes at

German and Italian tanks. One returned to

its base carrying 200 bullet holes, but was

still flying and fighting when the enemy dis-

appeared.

In a matter of days, Liberators bombed

three Italian cruisers in the harbor at Py-

los, Greece; joined the Russian air force at

Sevastopol; smashed at Bengasi; laid more

than 50,000 pounds of steel eggs in a second

slap at Suda Bay; roared over France to

attack Lille, Saint Nazaire, and La Palisse;

smashed installations at Hong Kong; raided

the Linshi coal mines in China. Now they

are hitting at the Axis in Tunisia, delivering

supplies and fighting men to distant Allied

Pacific bases, striking the enemy wherever

he can be found.

Hitler never will forget that Lille affair.

It was on October 9, 1942, when 115 Libera-

tors and Fortresses made a tight-formation

attack. Five hundred fighters accompanied

them part way, then swung aside to shoot

up several airdromes, hoping to lure Ger-

man fighters away from the main attack.

The bombers smashed a plant engaged in

building 150 main-line locomotives a year,

downed 48 Focke-Wulf and Messerschmitt

fighters, damaged and probably destroyed

59 others. American losses? Two Libera-

tors, two Fortresses.

Though her guns are deadly, her wing is

the real secret of the Liberator’s success in

waging long-range aerial warfare. We've

got to go back a bit for that story.

In the fall of '38, the Air Corps, scanning

the coming clouds of war, wheedled from

Congress an appropriation

to raise our force of mili-

tary planes from 2,500 to

10,000. Of these only 100

were to be big bombers.

Lieut. Gen. H. H. Arnold,

Chief of the Air Forces, or-

dered 100 Fortresses, the

only big fellows then avail-

able, and induced Boeing

and Consolidated to make

them, one by Consolidated

for every two by Boeing.

Then the Federal lawmak-

ers whacked the appropria-

tion in half, Boeing got

the order, and Consolidated

sat out in the cold.

But Arnold had a substi-

tute plan ready. He called

Edgar N. Gott, Consoli-

dated vice-president, and asked, “Can you

fellows turn out a long-range land bomber,

and how soon?” “We can deliver a bomber

in nine months,” Gott answered promptly.

All he had to rely upon for the promise was

Consolidated’s experience in building the

Model 31 long-range twin-engine flying

boat. Bombers those days could scarcely

clip off 1,200 miles. Gott knew he'd have

to turn out one capable of reaching Ireland

or Hawaii, in order to meet the demands of

the changing pace of air war.

Nine months and 10 acres of blueprints

slipped by, and the B-24 arrived. Would

she deliver, as the Army demanded, 307

miles an hour top speed, reach a 30,000-

foot ceiling, cruise at 220 m.p.h. three miles

up, and maintain a three-mile altitude with

two engines out? Could she cruise 3,000

miles without refueling ?

Her slick aluminum skin shone brightly

in the California sunshine, her tail arched

gracefully from her plump belly, her wings

stuck out stiff and stark. She was slightly

on the heavy side, but on that warm Cali-

fornia morning she flew gracefully, and that

instant was recorded a series of firsts which

marked her an airplane to be reckoned with.

For the Liberator was the first heavy plane

to use tricycle landing gear, first to em-

ploy Hamilton hydromatic quick-feathering

three-blade propellers, one of the first to use

Model R-1830 1,200-hp. Pratt & Whitney

radial engines.

Not much was left of Model 31 when the

first Liberator flew, except for the all-im-

portant item of the wing. As for weight,

she originally was scheduled to tip the scales

for a gross weight of 39,000 pounds. Short-

ly this was upped by a large amount.

You've got to look closely at that wing

for the main reason why Miss Liberator not

only flies farther and faster than other

heavy bombers, but also can lift heavier

loads than her predecessors. David R.

Davis gave Miss Liberator her wing. Davis,

once partner of Donald Douglas, upset all

previous theories of wing design when he

sold Major Fleet on an idea he promised

would give him a swifter bomber than man

had yet conceived.

To know about wings, you've got to un-

derstand that the efficiency of a wing de-

pends upon its silhouette and its airfoil,

airfoil meaning a cross section which shows

the curvature of its surfaces. Precisely the

form taken by the Davis wing can't be told

in a few sentences. Nothing less than a

complex formula would convey the idea,

even to an aeronautical engineer.

Nubbin of the idea, though, is this: Davis

theorized that, contrary to the accepted

thought, a wing has a positive action as it

moves through the air, and its seemingly

passive action is due to the fact it is held

passive by the plane's controls. From this

he concluded that, were a wing not held

passive, it would revolve like a wheel

around a hub. He reasoned further that a

wheel, properly modified, could be applied to

airfoil design.” His wing, then, can be con-

sidered a modified circle, which may be

varied to carry heavier loads, fly faster, or

perform whatever mission it may be called

upon to fulfill,

Davis’ wing was submitted to the Cali-

fornia Institute of Technology wind tunnel,

and to their amazement the scientists found

that it tested, not 90 percent efficient, which

had been about the best for any other air-

foil, but hit the unbelievable figure of 100

percent! They could scarcely believe their

own calculations, and almost tore the tun-

nel down in an effort to learn whether their

structure had contributed to an erroneous

total. But the figure stood, and when it was

applied to the Model 31 flying boat, the boat

took off like a land plane after an almost

incredibly short run.

Exactly what that wing might contribute

to America’s war effort was not immediate-

ly apparent, because we were not at war

and were not building big bombers in large

numbers. In December, 1939, though, the

nation got a preview of earth-jarring events

to come, when the first B-24 was launched.

To engineers, that ship promised great

things in the field of long-range flying and

bombing enemy bases a long way from our

bases with fairly heavy loads of deadly ex-

plosives.

Here you've got to consider another set

of facts about airplanes to understand why

Consolidated engineers were and still are

jubilant. Because we're coming to a new

era of even larger bombers, we'll talk in big

terms. Most planes, remember, carry a use-

ful load about equal to their own weight. A

bomber weighing 40,000 pounds ordinarily

will carry 40,000 pounds of bombs, fuel, per-

sonnel, and equipment. Now, if the wing's

efficiency can be increased 20 percent,

which just about represents the Davis

wing's superiority over others, that ship will

pick up a 40-percent heavier load, or an ad-

ditional eight tons. Because the Davis

wing has been found especially good as a

load-lifter, we can justifiably look forward

to Liberators' big brothers some day carry-

ing bomb loads far heavier than we've en-

visioned in the past—and carrying them

right into the heart of Germany and Japan.

The Liberator line is a dogged breed, as

one would expect from a warplane that has

proved its valor by great deeds. One is re-

ported by the British to have flown 745,000

miles—30 times around the world—during

the past year. An adaptation, the C-87,

flew 2,200 miles from Newfoundland to

England in 400 minutes, spanning the At-

lantic at 330 miles an hour. Another C-87

flew Wendell Willkie from London to Mos-

cow to Cairo. General Arnold flew in a

| C-87 from Australia to San Francisco in

35 hours, 53 minutes, establishing a world’s

record for that long over-water flight.

| The C-87, called the “Express Liberator,”

is a cargo and personnel carrier. Except

for a few changes, it is the B-24. Bomb

bays have been removed and windows in-

stalled. A new nose replaces the bombar-

dier's plastic windows. Obstructions have

been taken out and doors cut in her sides.

Though a land plane, she's been flying

scheduled ocean runs since last August,

hurrying officers, ammunition, and repair

parts to advanced bases. She's helping the

B-24 perform her important job. The quali-

ties that make her so useful are the same

ones that fit her bomber sister to be the

Liberator in fact as well as in name,

-

Autore secondario

-

Andrew R. Boone (Article Writer)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1943-05

-

pagine

-

86-91, 210, 212

-

Diritti

-

Public Domain (Google Digitized)

-

Archived by

-

Matteo Ridolfi

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Schermata 2022-02-24 alle 16.02.03.png

Schermata 2022-02-24 alle 16.02.03.png Schermata 2022-02-24 alle 16.02.10.png

Schermata 2022-02-24 alle 16.02.10.png Schermata 2022-02-24 alle 16.02.16.png

Schermata 2022-02-24 alle 16.02.16.png Schermata 2022-02-24 alle 16.02.26.png

Schermata 2022-02-24 alle 16.02.26.png Schermata 2022-02-24 alle 16.02.32.png

Schermata 2022-02-24 alle 16.02.32.png Schermata 2022-02-24 alle 16.02.37.png

Schermata 2022-02-24 alle 16.02.37.png Schermata 2022-02-24 alle 16.02.44.png

Schermata 2022-02-24 alle 16.02.44.png Schermata 2022-02-24 alle 16.02.53.png

Schermata 2022-02-24 alle 16.02.53.png