-

Titolo

-

Food from the wild

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Title: Food from the wild

-

Subtitle: Science ransacks nature to meet wartime food demands

-

extracted text

-

MEET a new kind of fishermen. Using

neither hooks, seines, oilskins, nor

rubber boots, they've caught a whop-

per which promises to change our diet.

President Roosevelt, himself no mean

wielder of rod and reel, arranged their fish-

ing party. It was with test tube and micro-

scope—and out of all the fish in the ocean

they found just the right one to meet a war

shortage. Their catch is the menhaden. If

you've never heard of it, you soon will. For

this prolific fish is the choice to pinch-hit

on the home front for the salmon going to

our overseas troops and our allies. It's

known off Jersey shores as the mossbunker,

heretofore regarded as a scrap fish.

That curious fishing expedition is but

one of the wartime activities of scientists

of the United States Fish and Wildlife Serv-

ice at the 3,000-acre Patuxent Wildlife

Refuge in eastern Maryland, You find them

carrying on, for the first time anywhere,

successful experiments in polygamist quail

breeding to speed propagation; they are giv-

ing the red fox and other prized fur-bearing

animals a new lease on life by their work

in disease prevention; they have figuratively

counted the noses of this nation’s big and

small game animals to the benefit of hunters

and depleted beef stocks; they have kept

a constant check on the flyways to protect

ducks, geese, and upland birds; they have

found new food for these birds and animals;

and, by a queer turn, they have brewed

poisons to take the place of poisons cut off

by the war that were our only means of

controlling the propagation of harmful and

destructive birds and animals.

Poison brewing became urgent soon after

the first torpedo of World War II exploded. |

Red squill, one of the most effective anti-

rodent poisons, came from the Mediter-

ranean area. Nux vomica, another death |

dealer, came from territory now overrun by

the Japanese. Thallium, perhaps the most |

deadly of all, came from Germany. Even

before the war, when these poisons were

easily obtained, the annual damage in this

country from rats alone amounted to $189,-

000,000. So the need for substitutes was |

great. |

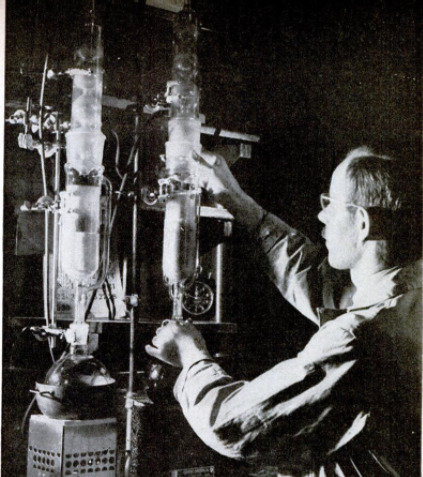

The Patuxent chemists tackled the job

with a pharmacological and chemical ap-

proach that revealed the poison principle of

the imported drugs. Then they attempted

to match it. Into their laboratory came hun-

dreds of native plants to be tested (or poison

content, Into thelr test tubes went scores

of chemical combinations Lo create syn-

thetic poisons. It wasn't long before they

had prepared 150 specimens. These were

rushed to the Fish and Wildlife Service

Iuboratories at Denver for actual tests in

killing. Findings showed the Patuxent chem-

ists had uncovered 10 American plants with

poisoning potentialities equaling those of

red squill and nux vomica. These plants, ex-

isting in great abundance, are Indian hemp,

calfkill, stagger grass, larkspur, American

hellebore, death camass, monkshood, Jim-

son weed, water hemlock, and poison hem.

lock, Poisons from these plants are ob-

tained by a simple process of distillation

and concentration.

When the war began making heavy in-

roads into our beef supply, the Government

again turned to Patuxent.” Experts there got

together data from all parts of the country,

announced there were 6,000,000 big-game

animals of which 600,000 could be taken

annually without endangering any of the

species. Thi represents 60,000,000 pounds

of meat & year for our dinner tables. Added

to this, the service estimated a possible

yearly Kill of 10,000,000 ducks and geese,

20,000,000 rabbits, 15,000,000 upland birds,

and 4,000,000 other small game.

Maintenance of this great potential food

supply was the tough problem. Present was

the danger of disease, shortages in wildlife

foods, and the elimination of certain species

by hunters. Research in disease prevention

and nutrition had been carried on by the

service for years, but under peacetime con-

ditions. New ways and means had to be

found. War made it virtually impossible to ob-

tain expensive test animals such as red fox and

mink. So the scientists turned to other sources,

and began breeding more ferrets, white mice,

and guinea pigs. They put hen eggs to an

amazing use. Kggs were placed in an incu-

bator until the embryo was well formed. In-

oculated with a virus or disease-producing bac-

teria, the embryo served as a living culture

medium within its own sterile package. It

took the place of living test animals in find-

ing protective and curative agents for dis-

eases of wildlife. Results of experiments

were passed on quickly to wildlife refuges,

naturalists, zoologists, and the nation’s fur

farmers.

Three thousand bobwhite quail were

raised at Patuxent last season, The main

objectives were to increase propagation and

to develop new quail foods that could be

supplied under war conditions. Both were

achieved. Quail are inveterate monoga-

mists. They were introduced to polygamist

breeding. Male birds were placed in pens

with three, six, and 12 females. The fer-

tility of the eggs fell off as much as 50 per-

cent as compared with normal mating, but

the increase In egg production spelled suc-

cess. The radical change in the quail's home

lie caused some disturbing incidents at first,

with an occasional death from fights caused

by jealousy. As the season wore on, how-

ever, most of the breeders accepted the new

setup.

The Patuxent scientists meticulously

charted a complete cycle in quail life—from

gE to chick to breeder to egg—keeping in-

dividual records of all birds raised. This

was important in developing the new diet

in which soybean meal, corn meal, and other

nourishing foods were used in place of ribo-

flavin concentrate, sardine fish meal, and

other things needed for the war.

Another task was the development of

natural foods for migratory fowl, About

half a mile from the main Patuxent labora-

tory is a series of 24 ponds, each 50 by 30

feet. There experts studied and experi

mented with aquatic and marsh plants.

Their findings may prevent the starvation

of great numbers of ducks and geese in

crowded breeding grounds.

With a million duck hunters in this coun-

try, it is imperative to have regulations

that will maintain the supply in sufficient

quantity to permit the annual forays to

‘marsh, lake shore, and river bank—in war

as well as in peace. These regulations are

not the vagrant thoughts of some official.

They are devised each year after long and

careful study by the Fish and Wildlife ex-

perts. The Patuxent Refuge is the clearing

house for all information used to establish

hunting and fishing laws. During migrating,

breeding, and wintering seasons, a constant

flow of reports comes from field personnel

and co-operating outdoorsmen.

The service's bird-banding system is a

source of information of the highest ac-

curacy. Of nearly 4,000,000 birds marked

with the numbered aluminum bands, 250,000

have been subsequently reported. This has

supplied a file of precise details on sex, age,

and migrating habits. Some ducks have

carried bands for 15 years, though the aver-

age bird is reported within two or three

years of banding. From the moment of

banding all information on the bird is tabu-

lated. Cards at the Patuxent refuge are

kept with the same care and, indeed, by the

same method as the Federal Bureau of In-

vestigation’s fingerprint system. The cards

are passed through a perforating machine

which notes number and other data. Later

it takes only a few seconds to locate the

cards by passing the file through a shuffling

machine. Wartime shortage of aluminum

has caused officials to cut down on banding,

but they are maintaining the status quo of

the system as far as possible.

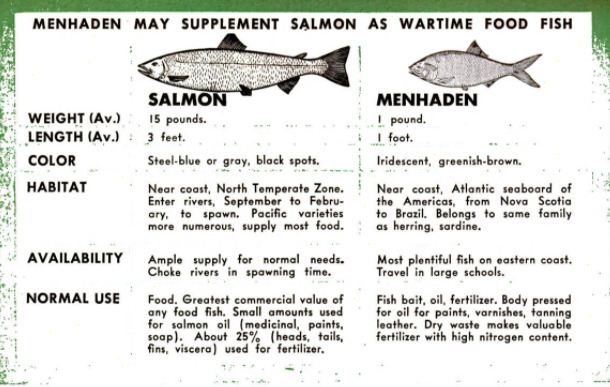

It was on July 21, 1942, that President

Roosevelt called on scientists of the Fish

and Wildlife Service to find a substitute

for salmon. What he hoped for was a fish-

ing expedition as successful as the one that

brought tuna—then unknown as a food fish

—to our dinner tables in the last war. What

he got was the menhaden, which not only

may surpass tuna as a tasty dish but vies

with salmon in food value and abundance.

Though its name is of American Indian

origin and its abundance has been known

for years, the menhaden has

never been sought for as food.

The millions of pounds taken

each year along the Atlantic

seaboard have been pressed

for oil and used to enrich the

soil. Much smaller than

either tuna or salmon —it

ranges from 12 to 16 inches

in length when mature—the

menhaden travels in great

silvery schools and is easily

captured with large nets.

In their survey, the Patuxent scientists

tested hundreds of American fish for edi-

bility and food value. For their purpose,

fish were hauled in off the rock-bound

coasts of Maine, the shores of Jersey, and

the palm-fringed Florida keys. Big fish and

little fish, deep-sea fish and estuary fish—

all were studied. Fish to be tested were first

canned at the Federal Fisheries Laboratories

at College Park, Md. At Patuxent, the

scientists removed the fish from the cans

and placed them in digestive racks—simply

glass retorts—which released the nitrogen

content as ammonium sulphate. The ammo-

nium sulphate was then placed in a Kjeldahl

distilling rack where the

‘ammonium was passed off as |

anitrate. By neutializing and |

measuring this nitrate, the |

chemists were able to calcu |

late the amount of protein in

each type of fish. They also

found that alewives, hake, |

and sea herring have a high |

food value and make very |

tasty dishes. So these, too, |

may soon find their way into |

our kitchens, —JACK O'BRINE,

-

Autore secondario

-

William W. Morris (Photographer)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1943-05

-

pagine

-

120-124

-

Diritti

-

Public Domain (Google Digitized)

-

Archived by

-

Matteo Ridolfi

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)