-

Titolo

-

German "Gothas" plane

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Title: The armored flying "tank"

-

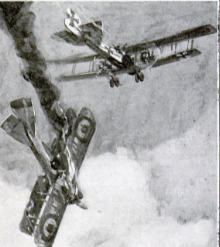

Caption: The big German Gothas carry 1200 pounds of bombs. Suppose the bombs were left just behind and just enough fuel carried for a two hours' flight. A lot of weight could be put in armor. We have indicated the armored portions by making them blacker. The wings are a lacework of ribs, so that a shot may pass through them without causing a complete collapse of the framing

-

extracted text

-

OVER the American sector, north

of Toul, a German biplane appears

—a giant with three cars. In the

central car sit a pilot and two observers;

in the side cars are the powerful engines.

Such huge, cumbersome machines are

usually employed for bombing—rarely for

combat. What an easy mark! Immedi-

ately two Americans start up, followed by

two others. At twelve thousand feet they

recognize the German for what he is—a

huge Friedrichshafen or Gotha. They

rush for him and pour in bullets. Nothing

happens. The bullets rattle off. The

German proceeds stolidly on his way.

Then Lufberry, the American “ace,”

leaps into the air. In his fast avion de

chasse he overtops the German. He

plunges down and fires as he dives.

Again and again he turns, climbs and

rains in bullets. The machine guns

manned by the two fighters in the German

machine vomit flame and lead. Suddenly

Lufberry is seen to lurch. Smoke shoots

up from his machine. He plunges. There

can be but one terrible end—death by

fire or death by a sickening fall. Lufberry

unbelts himself, rises, and leaps from his

machine. A bruised, almost unrecogniz-

able mass is picked up in a flower garden.

Thus the most famous American “ace”

meets a Homeric end fighting the first

steel-clad battle-airplane.

‘Why the Gothas Were Built

Now the idea of armoring an airplane

is not new. European powers had de-

cided that the weight required was pro-

hibitive. Why then did the Germans

succeed in solving the problem? Because

the Zeppelins failed. Zeppelins had been

successfully set on fire over London. A

substitute had to be found if bombing

was to be continued. And so the Germans

invented the Gotha biplanes—mammoth

machines driven by engines of unprec-

edented power, provided with fuel

tanks of enormous capacity for long

journeys, freighted with bombs weighing

hundreds of pounds. Their arc of fire was

not impeded in any direction. They could

even shoot at a lower enemy through a

tunnel. The British considered them

almost equal in speed to all but the most

recent small pursuit planes. True, they

were unwieldy; they could not perform

the gyrations of the smaller machines,

but they could fight off faster machines

armed only with fixed machine-guns

firing through the propeller.

The Gothas and the similar Friedrichs-

hafens and A.E.G.’s are intended to carry

much fuel for long raids and a great

weight of bombs. Suppose the bombs

were abandoned altogether? Suppose

that the radius of action, too, were re-

duced to that of a light, single-seated

fighter, so that only a little fuel—enough

for a two hour flight— need be carried?

And then suppose that the weight repre-

sented by bombs and excess fuel were

distributed in armor where it can do the

most good? That seems to be the under

lying idea of the new German battleplane.

Fully twelve hundred pounds of armor

can be hung on the machine’s vitals if the

principle is carried out. The essential

point is that in order to be immune to the

small fighting plane’s bullets the giant

Gotha requires but little more armor

for adequate protection than a moderately

sized machine.

‘The Merrimac of the Air

It is said that after Lufberry’s death

the German steel-clad flying tank was

brought down. Whether it was or not, its

appearance marks a new epoch in the

development of the military airplane,

comparable with. the revolution brought

about by the introduction of the

Merrimac in the Civil War. We must

cust about for a Monitor of tise alr. |

Size is in it-

self a kind of

protection; for

the larger the

machine, the

less are its

beams, ribs and

struts likely to

suffer from bul-

lets. Only a

small part of

the craft need

be encased in

steel. Since at

least every tenth bullet is explosive and

many more are burning torches, all

wooden and woven parts must be

chemically fire-proofed.

The latticed masts of American battle-

ships are so constructed that shots can

pass through them without necessarily

bringing them down. A similar principle

may be adopted in building wing frames.

Even now machine-gun bullets may rip

through the lace work of beams and ribs

of a wing without necessarily en-

dangering it. The whole tendency

in airplane construction is towards

such multiplication of ribs and

beams. Therefore armor need be

applied only to the fuel tanks (a

leaking or burning tank means a horrible

death by flames); to the controls (cables

leading to the rudders and ailerons must

not be cut); to the crew (a pilot killed

leaves the machine brainless);

to the guns (a sting-

less bee is no

more

help-

cartridges is the equivalent of an ex-

plosion in a powder magazine).

How are the fuel tanks to be de-

signed? The least possible amount

of material must be utilized and

yet the maximum volume OD-

tained by a shape approaching

a sphere’s. The larger the tanks

the better; for there is no pro-

portionate increase of weight

with increase of volume. An

empty 500-gallon tank does not

weigh a hundred times more

than a 5-gallon tank. Let the

steel be thick enough, and it

becomes bullet-proof without

other armoring.

The piping through which oil

and gasoline is conducted must

obviously pass through tubes of great

thickness; control cables must be en-

cased in armored tubes. Before the con-

trol wires emerge they are attached to

bullet-proof chains. The exposed part

of them must be shortened. The braces to

which they are fastened must also be

armored and joined to the rudder framing

at many

points. No

single hit

must disable

a control.

Like

the fuel

tanks,

the engines may be greatly increased in

volume and therefore in power without

proportionately increasing their

weight. Power depends on cubic

capacity of cylinders. Hence a big

engine may be armored, and yet its

weight will be proportionately no greater

than that of a smaller one. If the casing

is to be bullet proof its weight need not

be increased by more than three times.

Mail-Clad Knights of the Machine Gun

What of the crew? The pilot's is the

guiding brain. The gunners are the fight-

ers. Why not follow battleship practice?

Armor the cockpits—that is the first

thought that leaps to the mind. But

must we copy battleships? How different

are the conditions in the sky! The

single-seated one-hundred-and-fifty-mile-

an-hour fighter darts hither and thither

like a wasp at such close range that his

antagonist lives in the constant fear of

seeing him vanish only to bob up in some

new unexpected quarter. If the cockpits

are to be armored protection must be

provided on all sides. Do that and you

convert them into completely enclosed

turrets. But how can a man in a turret,

peering out of sighting slots, keep his eye

on an elusive wasp? And how can

guns be mounted in such a,

cramped quarters to

fire in all direc-

tions?

For the present, at least, turrets are out of

the question. ‘What then? A startling

plan suggests itsell: Armor the men in

the cockpit. The press reports of Luf-

berry’s encounter with the flying tank

state that the German crew were actually

clad in mail. The reason becomes more

and more obvious, The men have no

time to revolve a sighting slot, which, in

itself, limits their field of vision; they

have too many other things to do.

The suit of armor worn by each man

(a suit of far tougher steel than any

15th century armorer could have pro-

duced) must be a full suit. Remember

that the bullets may pour in

from any side. Body armor

~ is lighter by far than turret

= armor. Modern science will

make it far more flexible

than the medieval knight's

coat of mail. There is no

p- need for much muscular

| action in firing a machine

gun—scarcely as much as

was needed for poising a

lance. The mailed knight of

the Middle Ages was about

as awkward on foot as a penguin on a

beach. On a horse he was much like a

pilot in an airplane. He had only to

guide his horse and charge; the pilot has

only to steer his machine toward his

enemy. Armor the men in the machine,

and the task of aiming and firing a ma-

chine gun is not impeded. And so God-

irey of Bouillon, the Chevalier Bayard,

the crusaders whom we thought we

had buried for good when gunpowder was

invented are restored to us again—

knights of the machine gun skimming

over the clouds of a twentieth century

battlefield.

What next? We must evolve a

Monitor of the clouds to fight this sud-

denly created Merrimac. The armored fly-

ing machine must be met with the shell fire

of a small gun, something like the French

thirty-seven millimeter weapon. Such a

piece can be carried only on a machine as

big as the Gotha. Gone are the old wasp-

like tactics. Instead we see a more

stately maneuvering for favor-

able positions. The ranges in-

crease, Against shell fire ma-

chines cannot be armored heav-

ily enough, Once the nose-

spins, the-side-slipping, the tail-

dives, the dodging, the looping,

the “dead-leal” gyrations that

now characterize air fighting are

abandoned, victory must belong

to the more powerful gun, the

gun that can shoot accurately for

a considerable distance. Guns

have always won battles since

gunpowder was invented. It is

50 on land; it is 50 on the sea;

and it is 50 in the air. But ad-

mit this and once more the Zep-

pelin looms up as an efficient

possibility for long-range combat

against the sluggish, mammoth

cannon planes that are to play

the parts of aeriel Monitors. Be-

cause of their enormous lifting

capacity, because of their im-

mense size, Zeppelins can carry

a far more powerful battery

than any mammoth _steel-clad

flying machine, But if the Zep-

pelin_ reappears, why should not

its old enemy, the wasplike

single seated fighter also re-

appear? Why should it not be

sent against the Zeppelin as it was

sent against it so successfully over

London?

1t is a curious circle in which

we find ourselves revolving diz-

ally. The single seated wasp-like

fighter gives way to the armored

plane, the Merrimac of the air;

the armored plane gives way to

the cannon plane, the Monitor

capable of repulsing the aeriel

Merrimac; the cannon plane

gives way to the rigid, gas-in-

flated Zeppelin; the Zeppelin in

turn gives way to the small, elu-

sive, quick-maneuvering single-seated

plane. Surely the air navy of the future

must be a strange mixture of various types

of aircraft.

‘Who knows but it may become a hetero-

geneous collection of a few Zeppelins hid-

ing behind a vast army of flying machines,

differing in size as well as in construction

and armament!

-

Autore secondario

-

Waldemar Kaempffert, Carl Dienstbach (writers)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1918-07

-

pagine

-

37-40

-

Diritti

-

Public domain

-

Archived by

-

Filippo Valle