-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

Messengers of battle

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Title: Messengers of battle

-

Subtitle: It takes signaling as much as guns to make combat teams invincible

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

MODERN war is fought not only

to the chatter of machine guns,

but also to the chatter of teletype

machines. The jingle of a field-tele-

phone bell and the high-pitched,

staccato beeping of a radio code set

are as significant in their way as the

rumble of trucks or the barking

cough of a mortar shell.

For communications have become

the lifeblood of military operations.

An army which had every other

item of equipment for war, yet

lacked wire and radio communica-

tions, would be no better in the fast-

moving warfare of 1943 than a

blind, stupefied giant, stumbling

bravely but hopelessly to defeat and

destruction.

The task of maintaining com-

munications for the U.S. Army is

primarily the job of the Signal Corps;

within that Army the Corps’ func-

tion is roughly that of the nervous

system of a champion athlete. Our

Signal Corps, with its equipment

and men, provides the means by

which information is gathered and

transmitted from every part of the

Army's vast organism to its guid-

ing brain. Then back along the

same channels go orders and in-

structions. Without this interchange

of reflexes and reactions the Army

would not be a living mechanism.

Communications make it a co-ordi-

nated striking force instead of a

disorganized conglomeration of men

and machines working blindly in the

dark. The Signal Corps uses every meth-

od of communication, from the basic device

of having one man walk over to another

and tell him something, right up through

to the most precise and complex develop-

ments of advanced radio technology—de-

velopments which are still held as closely

restricted military secrets.

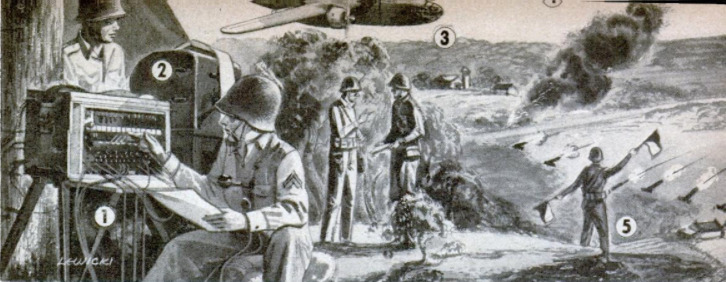

In between these extremes the Army em-

ploys messengers in vehicles (anything

from a motorcycle or a jeep to an airplane);

wire communication (telephone, telegraph,

and teletype) to the fullest possible ex-

tent; radio transmitters and receivers by

the tens of thousands. Older methods are

by no means forgotten; signal flags and

lights, flares and rockets, cloth panels, all

have their uses at times.

Naturally enough, how-

ever, the most striking Sig-

nal Corps developments |

since 1917-18 have been in.

the field of radio, and here

progress has been excep-

tionally fast in the last few

years. Army experts, work-

ing closely with U. 8. manu-

facturers, have designed and

perfected a whole series of |

special military radios, un-

surpassed by any such

equipment in the world.

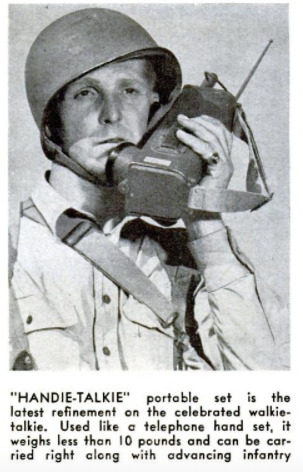

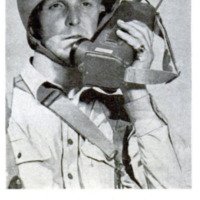

Among these is the amaz-

ing “handie-talkie” port-

able set, the latest refine-

ment of the walkie-talkie.

There also is a whole

series of new frequency-modulation radios

of medium range, developed primarily for,

artillery use. These sets may be used by

forward observers to order and direct field-

artillery fire. Other types are employed by

commanding officers to keep in touch with

the batteries in their command net. Voice

transmission has obvious advantages of

speed and flexibility over code for these

uses. FM transmission cuts through static

and local interference.

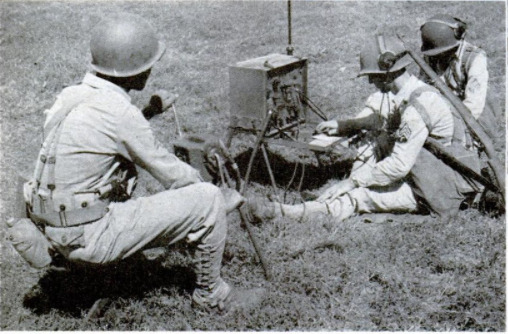

One of these sets designed for artillery

observers is mounted on a jeep, drawing

power from the car's electrical system

through a converter. But the radio often

must go up where even the jeep cannot fol-

low, so the set can be unshipped and car-

ried forward by hand, using battery power.

One husky man can haul it along, although

it is a rugged outfit weighing about 100

pounds. Another, more elaborate artillery

radio set, mounted in an officers’ command

car, can work a number of prearranged fre-

quency channels and is operated by push

buttons, much like those of a home radio.

Because of the global scope of U. s. mili-

tary operations, all this new Signal Corps

equipment has to be designed to function

equally well in the deserts of North Africa,

the bitter climate of Iceland, or the steam-

ing jungles of the South Pacific. For this

reason, all experimental models are put

through a brutal series of laboratory tests

—in steam rooms, refrigerator chambers,

blasts of sand or dust, showers of water.

After that come field tests, with the equip-

ment mounted in jeeps, trucks, or tanks,

pounding up and down over the worst test

courses the officers can devise.

The outfits that stand up—or that can be

redesigned and rebuilt to stand up—are

ready for anything. But even the best

equipment is subject to breakage, damage,

or failure in the field. The Signal Corps

pays special attention to field maintenance,

and has even planned and built a mobile

repair-shop truck, mounted in a bus body

and accompanied by a 1 1/2-ton cargo truck

towing a trailer.

Skilled technicians can make any type of

repair or adjustment in this shop unit,

which normally carries a crew of eight men

and two drivers. To protect the delicate

meters used, the workshop truck can be

closed up and air-conditioned.

The spectacular development of radio

communication in battle should not blind

us to the continuing importance of older

methods. If there is one thing above all

else that a good signal officer worries about,

dreams of, and battles to maintain, it is ef-

fective wire communication. And the wire-

communication system of 1943 is a vastly

different proposition from that of 1918.

The special advantages of wire over radio

are obvious. As one Signal Corps officer

expressed it:

“With radio, you get the sets, issue them,

and hope for the best. They're wonderful,

of course; we couldn't do without them. But

when you've got a good wire circuit in,

you're not kidding. It gives you direct, in-

stant, and private communication. The

enemy normally can’t pick it up with in-

tercept equipment or triangulate on the

sending source. Atmospheric interference

can’t blot your messages out. Yes, wire

may be hard to maintain, but it's awfully

easy to talk over.”

Wire-laying methods have been greatly

improved. Long experience has shown that

wire lines laid directly along a road are too

easily broken or damaged. Where the dis-

tances are not too great and considerations

of speed mot too pressing, the wire crew

tries to get away from roads altogether

and lay its lines across

country. Any truck

can serve as a wire

carrier, and when the

going gets too tough

even for the hardy

jeep, the crew goes it

on foot.

Where possible,

double circuits are

provided between im-

portant points. To

achieve this, a wire

crew may work its

way over rugged

country, then back

over a somewhat dif-

ferent route, laying

the second line, while

Army business al-

ready is flowing over

the first.

Probably the Army's

one favorite method

of communication is

neither the radio nor

telephone, but the

teletypewriter, which

gives direct private

connection, provides

an identical permanent record of every mes-

sage at both ends, and thus comes as close

as any human device can to eliminating the

possibilities of error.

A good field commander, however, isn’t

likely to waste much time arguing one

method against another. He is a glutton

for communications, and wants all he can

get of every type. His dream of perfect

happiness in this respect is to have all lines

of communication, from radio to carrier

pigeons, laid out in parallel and functioning

with faultless efficiency. It's never been like

that in any battle operation, but you can't

blame a man for wishing.

So far as it can, nevertheless, the Army

tries to back one communication line up

with another, and to give double or triple

protection for vital messages.

In a typical divisional front there will be

teletype, telephone, and radio circuits from

Army to Division HQ, and where possible,

teletypewriter from the rear to the front

echelons of the division itself. Telegraph

lines are laid to the infantry and artillery

commands, and from regiment to battalion

HQ. Phone circuits are laid to the regi-

ments and divisional artillery, and from the

regiments to battalions. The usual arrange-

ment in setting up wire circuits is that the

higher unit takes the responsibility of lay-

ing its wire to the lower (and more ad-

vanced) unit. Telephone exchanges range

from the divisional board, with 60 or 80

connections, to the

regimental field ex-

change, with 12 drops,

and the small battal-

ion board with six.

Radio nets from the

division HQ include

infantry regiments,

artillery battalions,

cavalry reconnais-

sance units, and any

special supporting

troops, such as can-

non company, anti-

tank company, engi-

neers, military police

company, or the like.

Infantry regiments

have radio nets to

their battalions, and

the battalion will have

handie-talkie radio

circuits to its com-

panies.

The total communi-

cations equipment of

a modern division is

a massive setup. The

signal Corps has the

responsibility of in-

stalling and operating all communications

equipment from the top command down

through the regimental echelon. More ad-

vanced units operate their own communica-

tions, but with equipment developed, tested,

and procured for them by the Signal Corps.

No one should get the idea, however, that

Signal Corps men do all their work far be-

hind the battle line. On the contrary, their

service is extremely hazardous; few mili-

tary objectives can expect to receive more

attention from the enemy than communica-

tions crews and installations. The World

War record of the Corps speaks for itself.

Out of a little more than 34,000 officers and

men in the AEF’s Signal Corps, 301 were

killed and 1,721 wounded or gassed. Only

the infantry had a higher percentage of

casualties.

In this war, Signal Corps men are seeing

even more vigorous action. The Corps is

now training members of the Women’s

Army Auxiliary Corps to replace enlisted

men as radio operators and mechanics at

certain Air Forces installations; the men

will thus be freed for front-line duties.

Americans have good reason to take

pride in their Army Signal Corps. This

branch of military service was originated

by us and copied by all the other armies

of the world. Signals—banners or horns

—had been used by armies since the dawn

of history, of course, yet little was done

to organize signaling as a specialized tech-

nique until nearly a generation after the

invention of the telegraph.

The world's first real Signal Corps was

founded in 1860, shortly before the Civil

‘War, when the U. S. Army granted the ap-

pointment and title of Signal Officer to a

young Army surgeon, Major (later Brig-

adier General) Albert J. Myer.

Since then the Corps has continued to

serve the nation in peace and war. Among

its peacetime services was the establish-

ment of the first national weather observa-

tion and forecasting service. No phase of

war has developed more strikingly in mod-

ern times than war communications, and

the Signal Corps has kept pace with that

growth. Its men are serving again now,

true to their terse combat motto: “Get the

message through.”

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

John H. Walker (Article Writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1943-06

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

49-53

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public Domain (Google Digitized)

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Matteo Ridolfi

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Popular Science Monthly, v. 142, n. 6, 1943

Popular Science Monthly, v. 142, n. 6, 1943