-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

The Bulldozer Grows Wings

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

The Bulldozer Grows Wings

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

WHEN United States troops invaded

North Africa, they included a small

group of soldiers the like of whom

the world had never seen. They carried

mechanized equipment which six months

before had been merely a gleam in an en-

gineer's eye. They were the first two com-

panies of Airborne Aviation Engineers, of

‘Whom there are now many more.

Within nine days these two companies of

airborne technicians with their novel equip-

ment helped to capture and repair a bombed

enemy airfield within a few miles of the

West African coast, and to prepare two new

fields in desert country a thousand miles

‘eastward on the Tunisian battlefront, along

Which our Flying Fortresses and fighter

planes went roaring into action.

The organization of these airborne avia-

tion engineers was a distinctly American

contribution to the art of warfare. They

were the brain child of Brigadier General

Stuart C. Godfrey, Alr Engineer, Directorate

of Base Services, Army Air Forces, The Gen-

eral, a graduate of West Point in 1009, com-

manded an engineer regiment in France in

World War I; and between military assign-

‘ments in peacetime wrestled with engineer-

ing Jobs on rivers and harbors {rom Panama

to Muscle Shoals. Aside from his engineer-

ing talents, he writes verse; he wrote the

Iyrics for the Army Engineers’ Fight Song,

for which his wife composed the music.

In the spring of 1042, the General was

‘pondering the dictum of General Henry H.

(“Hap”) Arnold, that air power is u three-

legged stool, of Which the three legs are

pilots, planes, and airfields. Without the

flelds, pilots and planes cannot operate. The.

effective range of bombers and fighters is

not entirely determined by their flying speed

and fuel capacity, but by the proximity of

thelr bases to the enemy.

In global warfare, and particularly In

island-to-island warfare in the Southwest

Pacific, the General ruminated, aviation en-

gineers should not be confined to the ground,

but be able to fly up fast to distant fronts

for construction, repair, and maintenance of

flelds; just us fast ax airborne infantry or

paratroops could seize a base for them, or

even faster In some situntions. The major

obstacle to this engineer's dream was the

size of all standard types of earthmoving

‘machinery. It was far too large to be flown

in airplanes. The major problem, therefore,

was to design such machinery on a much

smaller scale.

On May 14, 1042, the General wrote a let-

ter to the Chief of Engineers, U.S.A. asking

for help in implementing this idea. On June

8 a conference was held in hia office in

‘Washington, at which two men were as-

signed to develop plans for the new equip-

ment, and a table of organization for air-

borne engineer battalions who could use it.

These two men were Lieutenant Colonel

Elsworth Davis of the Engineer Board, the

Army Engineers research organization, and

Lieutenant Colonel H. G. Woodbury of the

Aviation Engineers.

With the enthusiastic help of manufactur-

ers scattered throughout the country, earth

‘moving machinery tailored to airplane meas.

‘urements was designed, built, and placed in

the hands of troops within four months.

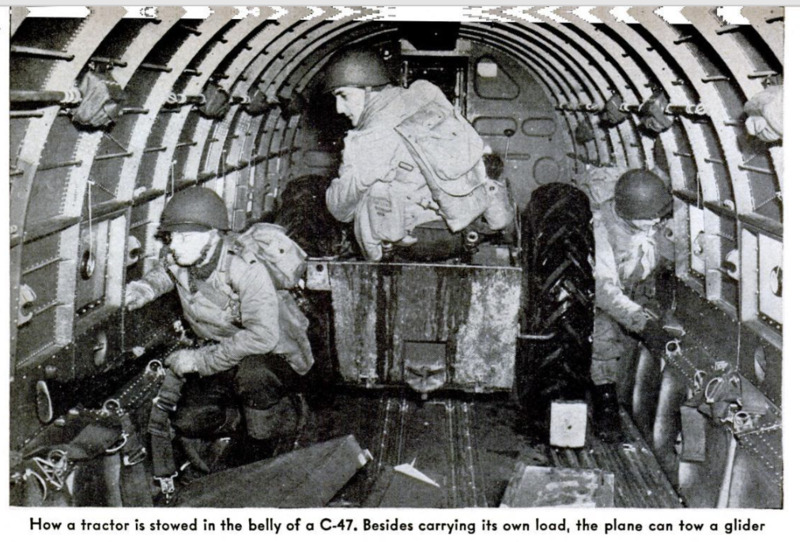

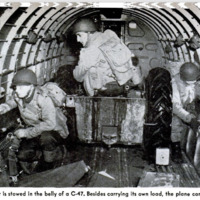

The C47 transport plane was then the only

available plane for carrying such oquip-

ment. A capacious cargo carrier, this plane

has a side door about seven feet wide by five

feet high, and had already proved useful in

carrying paratroops or nirborne infantry

with Jeeps or other heavy equipment.

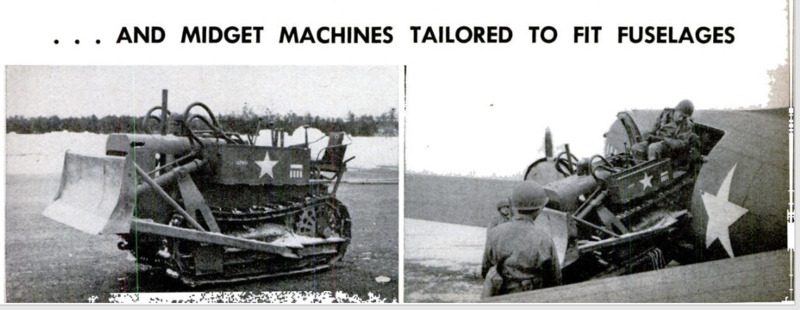

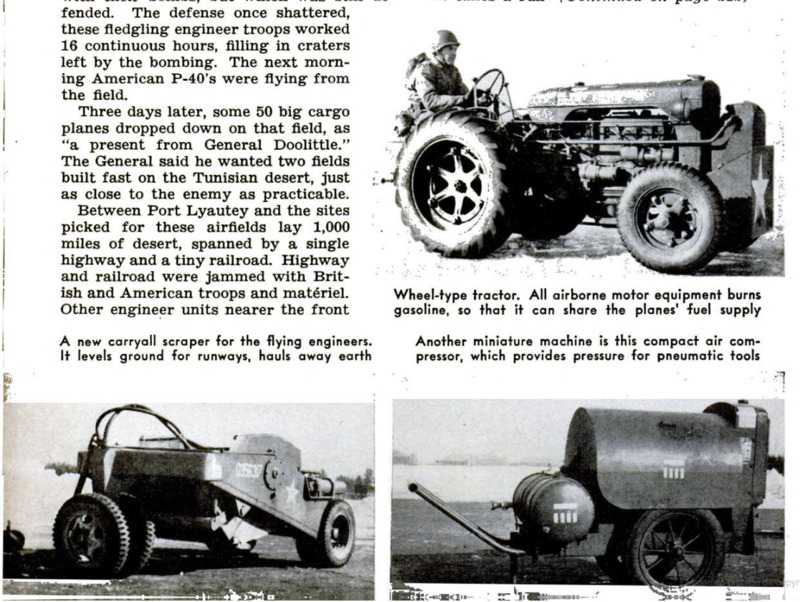

Small-uize bulldozers, scrapers, tractors,

graders, rollers, and asphalt heaters and dis-

tributors were bull to the limitations of that

airplane.

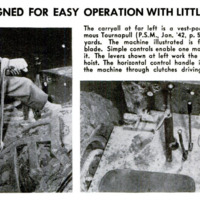

‘The bulldozer, as Its name implies, is an

instrument to push aside obstacles such as

dirt, stones, and trees, and to level the land

over which it travels. It consists of a tractor

with a blade like that of a mowplow. A

standard bulldozer, such as is used by Army.

engineers in general, weighs about 10 ton

and has a 10-foot blade. The new miniature

bulldozer, adapted for America’s airborne

aviation engineers from a model used by the

U. 8. Forestry Service, welghs only about

21; tons, has a blade slightly more than six

feet lon, and can easily be driven on a

ramp through the door of a cargo plane.

‘Standard bulldozers have commonly used

Diesel engines for fuel economy. The alr-

borne models are powered by gasoline en-

ines, so that the fuel will be the same as in

other Army mechanized equipment.

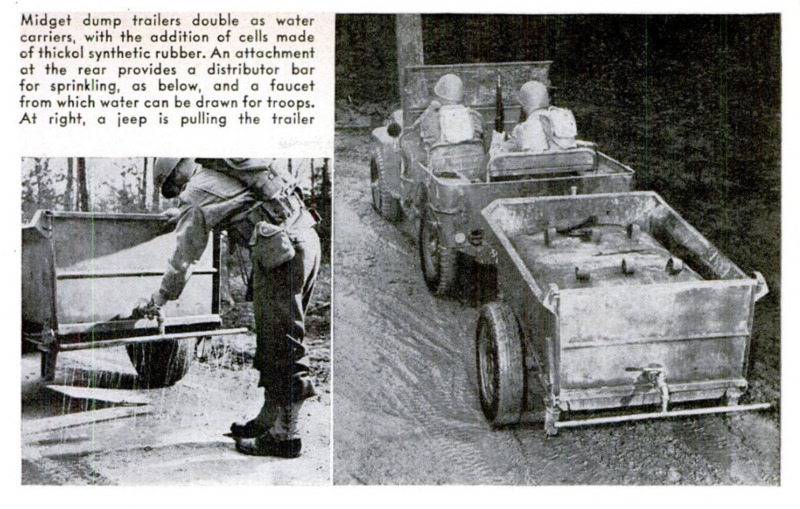

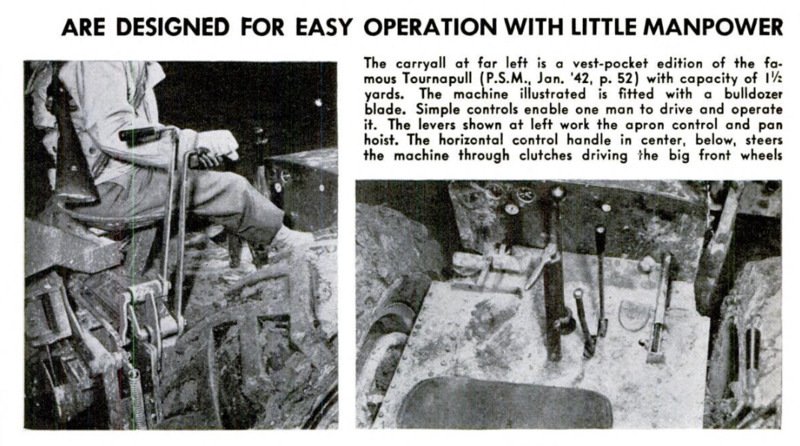

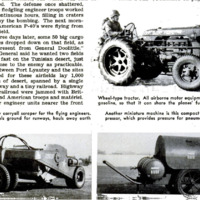

A new carryall scraper was designed,

which Is & combination blade and dump

cart, used to level elevations in any terrain

where a runway is being built, and to fil

In depressions. Standard scrapers for the

grounding engineers have been of eight-

yard capacity. They can dig up and haul

away eight cublc yards of earth. The min-

lature scrapers for the airborne engineers

are of 1 3/4 -yards capacity. Other new equip-

ment included a grader small enough to be

pulled by a jeep, and an asphalt heater little

larger than some office desks. There was

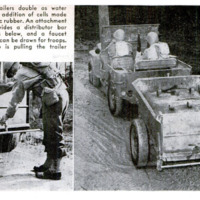

also a new-type roller, just a hollow metal

drum to be filled with water or sand on the

scene of operations, Empty, this drum

weighs about a ton. Filled, it weighs more

than three tons. A novelty in this Army-

designed roller is its attachable “sheep’s-

foot” studs. These studs can be fitted to

the roller on metal bands; as the roller re-

volves, they can tamp and compact an eight-

inch layer of earth. Specially designed water

purifiers and lighting units were also pro-

duced.

The first table of organization for the air-

borne aviation engineers was submitted by

Lieutenant Colonel Woodbury on July 9,

1942, and on August 18 the Adjutant Gen-

eral directed the First Air Force to activate

the First Provisional Airborne Engineer

Aviation Battalion at Westover Field, Mass.,

with a cadre, or skeleton organization, com-

posed of 100 volunteers from existing avia-

tion-engineer units. To help train this com-

. mand, and to carry equipment for it, the

Troop Carrier Command provided several

C-47 planes.

On August 29, Major General Jimmie Doo-

little, who was to command American air

forces in the initial African invasion, said

that if these new-type engineers could be

prepared in time he wanted them. A com-

mitment was made to have two companies

ready. As fast as the equipment rolled from

the factory assembly lines, it was flown to

Westover Field, and on October 8, just four

months from the initial planning conference

in General Godfrey's office, these two com-

panies, completely trained and equipped,

left Westover Field for an embarkation port.

On November 8, the first company of Air-

borne Aviation Engineers were part of a

combat team which landed on a hostile

coast near Port Lyautey, Morocco. They

rolled their toy equipment inland, and with-

in a few hours suffered their first casualties

while helping to storm an inland airfield

which U. S. Navy flyers had rendered useless

with their bombs, but which was still de-

fended. The defense once shattered, |

these fledgling engineer troops worked

16 continuous hours, filling in craters |

left by the bombing. The next morn- |

ing American P-40's were flying from |

the field. |

Three days later, some 50 big cargo "

planes dropped down on that field, as k

“a present from General Doolittle.” ;

The General said he wanted two fields |

built fast on the Tunisian desert, just ; of

as close to the enemy as practicable. \

Between Port Lyautey and the sites )

picked for these airfields lay 1,000 |

miles of desert, spanned by a single |

highway and a tiny railroad. Highway |

and railroad were jammed with Brit-

ish and American troops and matériel.

Other engineer units nearer the front

were wrestling with other jobs. The new

airborne aviation engineers flew the 1,000

miles to the front, and within three days

had a field ready for bomber operation. On

the fourth day they completed a field for

our fighter planes.

It takes a run-

way about a mile long, of level, hard-packed

earth, steel mats, or asphalt to make an

effective landing strip for our Flying For-

tresses. One somewhat smaller will serve our

fighter planes. On one of these jobs, the air-

borne engineers had some help from Arab

labor, paid in American cigarettes,

These two fields were a source of grief

to the Nazi forces in Tunisia, and to con-

voys coming up to supply them. Then came

Rommel’s short-lived attack, which over-

ran one field temporarily. When American

troops recaptured the field, they got a

chuckle. Our Aviation Engineers had been

forced to withdraw too fast to destroy all

their heavy equipment, but had camouflaged

it so well that the Nazi forces failed to

find it.

As now organized, each Airborne Avia-

tion Engineer battalion consists of a head-

quarters company and three construction

companies, with a strength of about 600 men

and officers. A lieutenant colonel commands

each battalion, and with him are seven staff

officers.

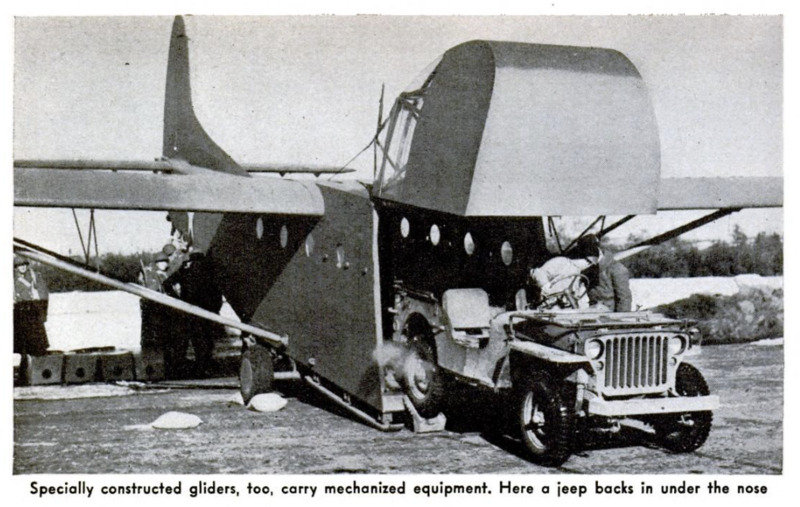

Each construction company has seven

tractors, three scrapers, two graders, a roll-

er, five jeeps, two trucks, and so much other

miscellaneous equipment that it takes be-

tween 15 and 20 of the big C-47 planes to

transport it. All the equipment is adapt-

able for use in gliders. Inasmuch as the en-

gineers must fight as well as work, they are

loaded with fire power: rifles, tommy guns,

pistols, carbines, and .50 caliber machine

guns with which to fight off dive-bombing

cad machine-gunning attacks from the air.

It takes five months to train one of these

companies; aside from their technical train-

ing, emphasis is placed on physical tough-

ening.

Obviously, the light equipment carried by

the airborne aviation engineers is not suited

to carry the main load of building the Army's

airfields. The standard-size, heavy equip-

ment being used by our aviation engineer

battalions around the world will always do

the bulk of the work. But the airborne unit

is now of proved value as a weapon of op-

portunity, adding flexibility and speed to

our forces in some situations. It bears about

the same relation to the heavy equipment

as does a light, quickly thrown ponton

bridge to the heavy, fixed bridge which is to

replace the ponton bridge later.

The airborne units will not be charged

with building or repairing elaborate ground

installations, or attempting elaborate cam-

ouflage work, though they are schooled in

rudimentary camouflage for self-protection.

Their job is to provide quickly the minimum

landing facilities necessary to allow planes

to operate.

In the case of captured fields, they may

fill bomb craters; neutralize contaminated

areas; help combat engineers remove booby

traps, mine fields, and other obstacles; con-

struct dispersal areas, and repair access

roads and all kinds of utilities. The portable

steel landing mats which are now being

shipped by the millions of square feet to our

airfields all over the world are too bulky

for much use by these airborne aviation

engineers, except in small quantities for

patching and special jobs.

Essentially, these new troops are pioneers,

adding to the speed of air war, the speediest

war there is. Their ranks are open for tough,

skilled men who are looking for plenty of

action,

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1943-06

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

66-70, 212, 214

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public Domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Matteo Ridolfi

-

Alberto Bordignon (Supervisor)

Popular Science Monthly, v. 142, n. 6, 1943

Popular Science Monthly, v. 142, n. 6, 1943