-

Titolo

-

Smoke Cover for Land Units Protection

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

"Smoke" Armor. The army finds a magical way to hide troops, ships, factories and even cities in chemical haze made from a formula by Dr. Irving Langmuir

-

extracted text

-

Plazes bombing by daylight, such as

American Army fiyers are doing with

deadly effectiveness in Europe, is absolutely

impossible for enemy airmen on at least nine

days out of ten in several of the most vital

defense areas of the United States. No bomb-

sight can pierce the vast artificial fog which

our Army's mew M-1 smoke generator

throws out as a screening blanket over mili-

tary objectives.

An armor of artificial haze or fog has so

proved its effectiveness in North Africa that

one German bomber pilot was heard com-

plaining by radio in mid-air to another that

he couldn't find his target “because of that

damned smoke.” On the field of combat

large-area smoke screening has made dive

bombing or torpedo bombing absolutely im-

possible where used over concentrations of

men or ships.

The use of smoke to blind an enemy in

warfare is an old story. But the Army's

M-1 mechanical smoke generator is some-

thing so new that several key principles

basic to its successful performance still are

military secrets. It may be told, however,

that with a few of our latest generators a

few hundred men or women operatives can

absolutely blot out areas as large as any of

America’s strategic canals, navy yards, air-

plane factories, or other military supply cen-

ters from the view of enemy airmen, on al-

most any day or night in which flying is

possible.

What nobody can see, nobody can bomb

with precision. The R.A.F. found that out

when trying to destroy the cruisers Scharn-

Horst and Gneisenau in the harbor at Brest.

For many a day British airmen dropped

their missiles hopefully toward these valu-

able targets. Those cruisers escaped. One

reason they got away was the Germans’ use

of a protective smoke screen all around them

—a screen now antiquated as compared with

America’s latest invention for the purpose.

Before Pearl Harbor, the Army set out to

improve American smoke-production meth-

ods as swiftly as possible. Smoke generators

now growing obsolete were already in use

for the screening of limited areas, but what

the Army Service Forces wanted was a de-

vice for screening many square miles, if

necessary.

One of the. most widely used methods for

production of smoke screens at that time

was the partial burning and distillation of

low-grade fuel oils in generators similar to

the orchard heaters and smudge pots used

in California fruit groves.

These oil smoke pots—the best we had—

produced a dark-gray smoke which was ef

fective in obscuring small areas, but their

use was expensive in men and material. The

smoke pots had to be serviced frequently,

almost every hour through the nighttime,

when they were used. They required many

men for operation, and provided little or no

protection if used during the daytime. The

smoke emitted was irritating to the noses

and throats of people in regions protected.

It stained their clothes and hampered their

work.

The job of developing and providing smoke

chemicals and devices is entrusted to the

Chemical Warfare Service under the Army

Service Forces.

No method of smoke projection existed

capable of the large-area daytime screening

which this Service sought. The problem of

finding one was put up to the National De-

fense Research Committee, headed by Presi-

dent James B. Conant of Harvard. This is

the committee, established in 1940, which

has enlisted about 6,000 scientists in 100

schools and 200 industrial laboratories for

war research service, and which in Januar,

1943, was wrestling with about 1,400 re-

search jobs for American armed forces.

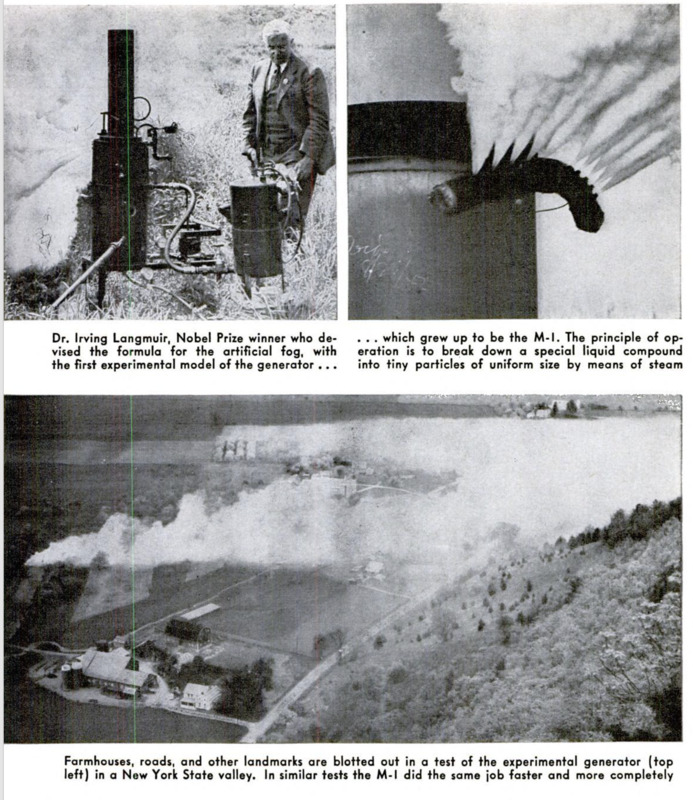

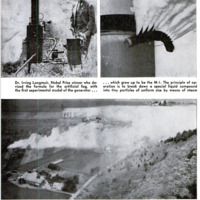

One of these scientists is the Nobel Prize

winner, Dr. Irving Langmuir, physicist at

the General Electric Company's research

laboratories, Schenectady, N. Y. Dr. Lang-

muir was one of the men asked by the

National Defense Research Committee to

seek the better smoke formula,

At the moment, Dr. Langmuir and an as-

sistant, Vincent Schaefer, were knee-deep in

a study dealing

with gas masks. Research into screening

smokes fitted into their thought and experi-

mentation. Dr. Langmuir approached the

problem of a smoke screen from the purely

scientific viewpoint of obscuring physical

objects by obstructing or diverting all rays

of light by which they could be seen.

He concluded that the effectiveness of any

smoke must depend on the size, density, and

color of the smoke particles. He concen-

trated on the ideal particle size. Having ar-

rived in his mind at that ideal size, he

turned the job of producing it over to his

assistant, Mr. Schaefer, who built a big

“smoke box” on an upper floor of the Gen-

eral Electric Laboratory. Soon from that

upper floor there poured out such smoke

that once the factory fire department came

rushing to the scene to douse a nonexistent

blaze.

Schaefer made five model devices before

he found one which apparently turned out

the proper smoke particle, a liquid globule

of microscopic proportions. He could mount

to the top of his smoke box after creation of

a smoke screen within it, and look down up-

on that layer of cloud as an airman today

looks down on the screens that are set up

over American military targets by special

smoke companies of the Chemical Warfare

Service. He tested its obscuring power

against various colors and shapes, with

screens of varying thicknesses and heights.

Then the National Defense Research Com-

mittee brought in the Standard Oil Develop-

ment Company's industrial production en-

gineers to build a model unit for producing

the Langmuir-Schaefer type of smoke screen

in quantity. These engineers designed and

produced within a month the first smoke-

generator unit, working on the job of break-

ing down a special liquid compound into

tiny particles of uniform size by use of

steam.

The unit produced was an odd-looking con-

traption—as most of its successors are to-

day, although new designs are now being

made. On the back of the M-1 generator are

three cubicle tanks, joined together to look

like one big box. These carry sufficient

smoke materials for long-time operation. In

the middle of the contraption is a small

gasoline motor, and at the front is a big

cylindrical boiler, with a number of little

vents on a horizontal pipe through which the

smoke clouds are ejected. The whole thing

looks a little like one of those horse-drawn

fire engines of the gay nineties, once it is

‘mounted, as it always is for mobility, upon

a four-wheel trailer. 1t is just a machine for

driving heated smoke compounds through

spray nozzles.

Its designers called the first unit “Junior,”

in affectionate irony, to distinguish it from

some other experimental smoke generators,

then in the making. “Junior” was a military

code word that now has lost all military

significance.

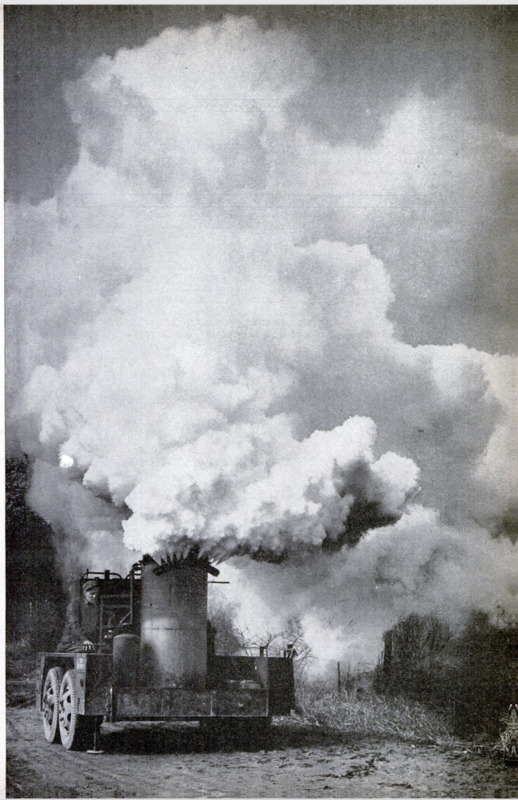

On June 2, 1942, they trundled Junior up

into the Schoharie Valley, a few miles away

from the General Electric plant at Schenec-

tady. On a cloudless, sunny morning, with

only a light wind blowing, the producing

scientists, industrial engineers, a collection

of Army and Navy officers, and some repre-

sentatives of the Canadian National Defense

Research Council went out to see the ma-

chine in action. The onlookers climbed to

the top of a steep cliff, about 600 feet high,

from which they looked down at some miles

of rolling farmlands and surrounding hills.

First they saw a few smokes emitted by

some other generators. These were not im-

pressive. Then “Junior” went to work. From

his one big boiler there came rolling out a

white mist which blotted from view several

miles of the valley within a few minutes.

Close to “Junior's” ten-lipped mouth this

haze was a billowing, swirling smoke cloud

—the kind of dense rolling smoke one might

see in the burning of a great pile of autumn

leaves, only whiter. As it spread out, how-

ever, it was the kind of fog one may see

hanging low over swamps on misty morn-

ings, obscuring all vegetation and wildlife.

Everybody who saw it knew they had

what they were after. If one such contrap-

tion could blot out miles of field and high-

way, and render invisible all distinguishing

marks of the countryside such as groves and

farmhouses, a few dozen could blot out cities.

The machine was taken to Edgewood

Arsenal, that center near Baltimore, Md,

where the Chemical Warfare Service manu-

factures much of the nation’s chemical

warfare equipment. It was tested again.

Officers found that they could walk through

the clouds of billowing fog without the dis-

comfort that came from the old smoke pots.

The haze that encircled them did not soil

their clothing. It was an atmosphere in

which they could continue to work. That

artificial fog had an amazingly high per-

sistency. In succeeding tests it was found

to hang together for as much as 20 miles

downwind, and to obscure all land for at

least half the distance.

Contracts were let for the manufacture of

these M-1 generators. As the machines

rolled from the production lines, they were

used in amphibious training operations on

Cape Cod, Mass. Their white mist quite

blanketed a shore line and stopped traffic on

surrounding roads for miles. A group of the

generators was tried at an Atlantic port

where important naval operations were

under way.

On 10 out of 11 days, this haze not only

hid all outlines of the earth beneath them

from watching flyers, but persons on the

ground in the area of operation found they

could continue their work with little handi-

cap. In November, 1942, when United

States forces made their landings in North

Africa, companies of smoke troops, armed

with these generators which had not been

in existence five months before, proved the

worth of the new device on foreign soil.

Later it was announced that a smoke screen

had been thrown over the Panama Canal as

a test, which effectively obscured that mili-

tary target for many miles.

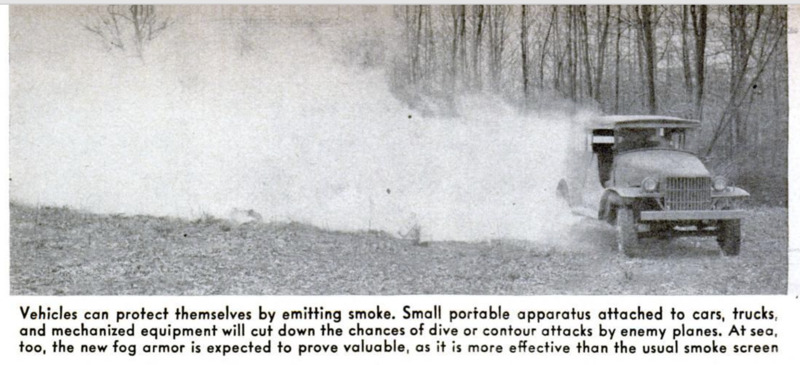

Today the tactics of large-area smoke

screening are being developed rapidly. Each

area to be obscured has to be treated ac-

cording to local conditions of wind, weather,

and terrain, which vary from day to day.

but which have certain averages. Generators

ordinarily are stationed at selected points to

‘windward of the places to be screened, and

are moved as the wind shifts.

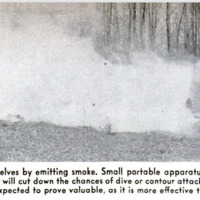

In case of air-raid alarms, smoke blankets

are started from the generators closest to

the most vital points for protection, the dis-

tance depending on how hard the wind is

blowing. A second line of generators then

starts to work some 400 or 500 yards to

windward. As their smoke reaches the vital

point and covers it, the generators originally

closest in will be moved back to positions

still farther to windward.

‘As soon as an unbroken smoke blanket

extends from the outermost generators to

the vital point, such as a factory, power

house, or dock line, the area of the blanket

will be gradually enlarged by moving gen-

erators constantly backward until finally the

‘eginning of the screen may be several miles

from the point which enemy aviators pre-

sumably are seeking.

The generators farthest back from most

vital targets will be located on broken lines,

50 that the smoke or haze does not neces.

sarily appear as artificial to an enemy bomb.

ing pilot, but may produce the illusion of a

Datura phenomenon.

‘Around a harbor, on lakes or rivers, the

generators may be placed on barges when

Decessary to get them upwind, and special

barges have been designed for the purpose.

This obscures shore lines.

It is easy to imagine the difficulty with

which a bombardier is faced when he finds

himself over a target covered with smoke for

‘many square miles. He must either drop his

‘bomb indiscriminately in the smoke with

faint hope that they will damage some im-

portant installation in the area, or he must

find a target that is uncovered in some other

area. That choice is not an easy one.

It a pilot has come several hundred miles

with & mission of bombing a power station

oF an oll refinery and knows that his target

is somewhere within the smoke, he may be

inclined to take a chance and hope that his

bombs will reach their objective. An al-

ternative target which may have been as-

signed may also be screened or it may be

protected by powerful antiaircraft artillery

defenses.

The American theory of bombing lays

great stress on accuracy. Our Air Force

believes our bombardiers can hit a reason-

‘able percentage of their targets. We believe

that point bombing is more profitable than

‘area bombing. Smoke properly placed makes

point bombing impossible.

In the daytime the screen is wide enough

and high enough to cover not only the vital

target, but also most aiming points or land-

marks by which a bombing plane flies

toward its goal. At night a dark-colored

screen not only obscures a target but also

camouflages all ita surrounding region. Gray

smoke, even in the moonlight, has all the

appearance of a body of water when seen

from high altitudes. A pilot or navigator,

‘seeing what looks like a large lake where he

expected to see land, may become confused

as to his position.

“The development of this new machine for

large-area smoke screening, capable of pro-

ducing 50 to 100 times as much smoke with

less cost and less human effort than any pre-

vious smoke apparatus, is one of the major

triumphs of American science in helping to

fight the nation's war.

By the aid of industry. the size of present

smoke generators should soon be cut down,

30 they will be easier to handle and consume

less cargo space when shipped overseas. The

3-1, now the Army's standard, is far heavier

than future machines will be. A model which

is only a small fraction of its size has beer.

developed, and should soon be in production.

Used today exclusively by soldiers, these

generators are so simple to operate and

maintain and require so little heavy labor

that there is no reason why they should not

be operated within the zone of the interior

by limited-service troops or by women. Their

operation by WAACS has been considered,

to release fighting men in some areas for

other duties.

-

Autore secondario

-

Alden H. Waitt (writer)

-

Allen Raymond (writer)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1943-07

-

pagine

-

62-63, 194-196

-

Diritti

-

Public Domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by

-

Matteo Ridolfi

-

Alberto Bordignon (Supervisor)