-

Titolo

-

U. S. bomber flyer's deposition

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

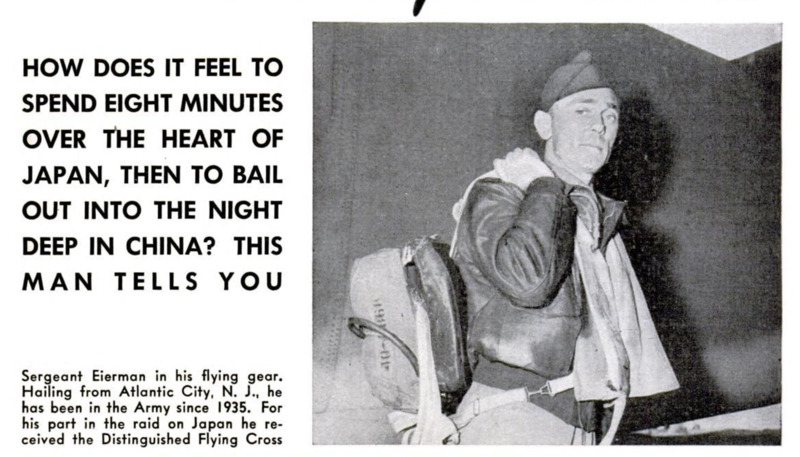

I Helped Bomb Japan. How does it feel to spend eight minutes over the heart of Japan, then to bail out into the night deep in China? This man tells you

-

extracted text

-

I FLEW on the Japan

raid, and it was the

biggest show I've ever

had a part in. I'd call

it a thoroughly successful operation. I know

that one bad break forced a change in the

plan, and later led to the loss of our planes

and a few of our men. But every plane went

where it was supposed to go, found its tar-

gets, and planted its bombs right where

they were supposed to fall.

I have been in the Army since 1935, when

I enlisted in the infantry. I transferred to

the Air Corps in 1936 and trained at Wheeler

Field as an engineer-gunner. Early in 1939

I was sent back to California and assigned

to my outfit, the 89th Reconnaissance

Squadron. All the men on the Japan raid,

by the way, came either from the 89th or

the 17th Bombardment Group.

Early in 1941 we got our B-25 bombers,

North American Mitchells. In February,

1042, word went around that volunteers

were wanted for “P.” That was our code

‘word for a special mis-

sion somewhere out-

side the country.

There were more

volunteers than they could use, so we drew

lots, both officers and men. My name was

the first drawn in our squadron.

‘We did our main training at Eglin Field,

Florida. There we worked and worked on

short take-offs with markings on the run-

ways. We also had gunnery and bombing

practice, and did long navigation missions

of eight and 10 hours, practicing celestial

navigation out over the Gulf.

Of course, the boys had some theories

about the nature of our mission. One was

that we were going to blast a big submarine

base in the Caribbean. But that was settled

when we went to the West Coast and got

charts that showed pretty clearly that we

were somehow going to China by way of

Japan.

We removed our lower turrets to install

extra gas tanks, and also had tanks in the

bomb bay and the crawlway leading to the

rear of the plane. After a final checkup we

went to the West Coast, then flew to a

rendezvous where our planes were loaded on

the flight deck of the aircraft carrier Hornet.

At 8:30 the next morning we sailed out

to sea, where we met up with cruisers and

destroyers which went along with us.

The weather almost all the way across

was dreary, misty, and rainy. Occasionally

we'd see the sun, but most of the days were

pretty bad; that was excellent for us. For

the first part of the trip it was a pleasant

life, We ate and lived with the chief petty

officers, and the food was swell. On a typical

day we could get up when we felt like it and

get breakfast until eight o'clock. Then we'd

go on deck and check up on our planes, ad-

just them, and go over equipment. To keep

in practice, we flew kites and fired at them

with the top-turret guns of our planes.

Every day General Doolittle held a meet-

ing with a lecture of some kind, on gunnery,

navigation, first aid, or bombardment. One

day a naval officer who had been an attaché

in Tokio talked about the terrain of Japan

and told us ways to tell a Chinese from a

Japanese, There wasn't time to learn any

language, but we memorized a Chinese

phrase, “Meg Wa Bing,” meaning “Ameri-

can Soldier.”

Our planes made the whole trip lashed to

the top deck. We had them dispersed around

so they covered the entire deck. It was

understood that if we were attacked we

would take off immediately and try to land

wherever we could—first at Hawaii and

later at Midway. If there wasn't time for

that we were to push our planes overboard

so that the carrier could get her own fight-

ers in action.

After we got west into the danger zone,

we had general quarters every day before

dawn and before sunset. After sunset gen-

eral quarters we'd have supper and in the

evening there wasn't much to do except talk

or play the old Navy game of acey-deucey.

We had been turning the engines of our

planes over every other day to keep them

tuned up, and now we refueled the planes

completely on the afternoon of April 17. We

understood that the plan was for us to take

off in the late afternoon either on the 18th

or 19th, when we would be about 400 miles

from Japan. We were to hit there around

dusk or a little after, and General Doolittle

was to go over about an hour ahead with

incendiaries to light up one main target so

that the rest of us could get our bearings

on that.

But it just didn’t work out that way. On

the morning of the 18th we suddenly sighted

a small vessel. It could have been a fishing

boat or a patrol boat, but we never knew.

One of our cruisers fired two salvos at it.

The first was just over, and after the second

there wasn't any more target to shoot at.

But there was no way to tell whether the

boat had got off a radio message, so the

decision was made to begin our raid im-

mediately, and the order, “Stand by to

launch your ships” came over the carrier's

loudspeaker system.

We had no chance to eat breakfast, and

most of us took off with empty stomachs.

The Navy did rustle some sandwiches for us,

though, and we took them along. Each man

also was issued a pint bottle of whisky for

emergency use.

We reported on deck and went directly

to our 16 planes, which were now grouped as

closely as possible at the back of the deck.

There were 80 of us in the plane crews—

five to each ship.

We knew we were going on a tough job.

At the plane our pilot, Maj. John A. Hilger,

told us we probably just didn’t have enough

gas.

“The way things are now, we have about

enough to get us within 200 miles of the

China Coast, and that's all,” he explained.

“If anyone wants to withdraw, he can do it

now. We can replace him from the men who

are going to be left aboard.

Nothing will ever be said

about it, and it won't be held

against you. It's your right.

It's up to you." Not a man

withdrew, although I don’t

suppose any of them felt any

better than I did.

The first ship was ready to take off about

8:20 a.m., and we all stood around, watching

and sweating it out. We had done plenty of

practicing—on land—but this was going to

be the first real take-off from a carrier with

one of our big bombers. To make it worse,

the sea was kicking up nasty and the

carrier was rolling and pitching.

But General Doolittle went first. He just

set the brakes, gunned his engines, got his

signal from the carrier's control officer, and

took off. He used only about 200 of the

300 feet of runway he had, and just seemed

to jump the plane off into the air. Every-

body felt better after seeing that.

The toughest thing about the take-off, by

the way, wasn't the run itself; it was the

fact that our bombers had less than six feet

clearance between the right wing tip and the

“island”—the big bridge structure of the

carrier. That was the worst hazard. After

four or five ships got off, one plane started

without lowering the wing flaps. It ran

right off the end of the deck and seemed to

drop, but the pilot managed to keep off the

water and gained altitude slowly. He was

all right.

Finally our turn came, and there were

two other ships left to go. It felt like a

normal take-off except for the very short

run. The rolling and pitching was so bad

that it took 15 men to hold the plane steady.

The biggest thing I remember about that

take-off was that I saw the carrier take

water over her bow just as we were heading

down to it. Major Hilger and the copilot,

Lieut. Jack A. Sims, were in their regular

places and I was crouching directly behind

and between them. Lieut. J. H. Macia, the

navigator-bombardier, was in his navigator's

place, and Sergeant Bain, our radio oper-

ator-gunner, was at the radio desk.

We got off, circled the ship once to check

our compass, course, and drift, then started

off. There was no flight formation. Each

ship was on its own, with orders for its own

targets. All the way to Japan we never

went above 50 or 60 fect, and much of the

time we were down around 15 or 20. We saw

one amphibian patrol plane about 400 miles

from the mainland, but it was at 3,000 feet

and never saw us at all.

Nearer Japan, we passed several small

boats and the people stood on deck and

waved to us. They seemed to get quite a

kick out of seeing “their” planes patrolling

s0 close to them. We tried out our machine

guns and the nose gun jammed and couldn't

be cleared. But the pilot ordered me to stay

in the nose and be ready to drop the bombs

if anything happened to Lieutenant Macia.

We approached land skimming the waves

at 20 feet. I guess we had all been hungry

and no one realized it. But just as we came

in over land. Sergeant Bain started eating

a sandwich—1I remembered that later.

By then we were all thinking about our

bombs. Our ships carried some demolition

and some incendiary bombs. We had a

special load of four 500-pound incendiary

clusters—that is, each cluster contained 128

four-pound incendiary bombs. Before the

take-off we had watched a little ceremony

on board, when the carrier's captain went

up and attached some Japanese medals to

the first bomb that was going to be dropped

from General Doolittle's plane.

We came in Over Japan just above the

treetops. Tt didn't look na’ cluttered and

crowded as wo had expected. It was like a

rural district anywhere, with green fields

nd open country. It Waa a brilliant. sun

shiny day by now, without a cloud in the sky.

Our target was Nagoya, u big industrial

center, ike Pittsburgh in the U.S. We hit

there about 1 pm. after circling from the

buy %0-as to come back and make our run

from the inland. We knew Tokio must have

caught it nearly an hour before, yet no ono

heered ready for us. Wo had no trouble

locating our targets, which were zigaagged

on either aide of a very prominent straight

Canal leading to the bay. There was no

AA ‘fire, and not another plane in the sky.

“The first target was u bg army barracks

near the Nagoya Castle, an ancient. land-

mark. We were now at 1.500 foct and doing.

200 miles an hour; that had been arranged

in advance 80 we could uso the improvised

“20-cent” bombaight. We did not carry the

regular Norden ‘hombeight for fear one

might fall into the enemy's hands

We let our first cluster go on the barracks

and Just then somo flak began to come up.

They weren't too close— black puffs that

looked like 37.millimeter stuff, Tho funniest

reaction was from Sergeant Bain. I heard

him on the plane's intercom phone, saying,

“Major Hilger, sir, those guys are shooting

at ual” He waa talking in an indigaant

Carolina drawl, and he sounded just ux

though he figured those fellows wera break-

ing the law.

“The Japs couldn't seem to got our speed

and aliitude right. Some of the stuff was

50 far off It. didn't seem that they were

really trying. I saw only one mark on the

plane—a little hole near the running light

On the left wing tip.

Our second target was a big arsenal or

some kind of army depot. Now, I hadn't

seen the first bomb land, but I sure saw this

one; it went right down on the target,

dispersed beautifully around it and hit

particularly hard around one corner.

The third target was an oil-storage ware-

house. I saw that one and it seemed like

a perfect hit. The AA fire slowed down

then; I suppose we had run out of the area

where the guns were. But it started up

harder than ever as we approached the

fourth and last target, the Mitsubishi air-

craft works. That was a beautiful hit, too. T

could see the bombs strike and flames burst

up all over it. Of course we couldn't stick

around long enough to check up on exactly

how much damage we had done. I saw a

funny thing there, too. As we passed over,

a cleaning woman rushed out of one door

and shook a mop at us!

Major Hilger suddenly called out: “Look,

they've got a ball game on over there. I

wonder what the score is.” It was a baseball

game, sure enough, and a big crowd was in

a wild scramble getting out of there fast.

With our bombs gone we went down to low

altitude again and came out over the bay.

We had one more target—oil tanks on the

waterfront to be blasted with .50 caliber

machine-gun incendiary bullets. Sergeant

Bain, in the top turret, cut lose at them, then

climbed down. I looked at him and burst

out laughing. His left fist was clenched

tight and his fingers were oozing peanut

butter and jelly from that sandwich he had

started to eat as we swept in over Japan.

The whole raid had taken us about eight

minutes, and he had never let go.

* Well, with the excitement over for a

minute, anyway, we felt a little let down.

We did see one plane back of us over the

city and it suddenly disappeared in a big

cloud of AA fire. We know mone of our

planes was shot down, so I've always sup-

posed some Jap ship came along and caught

it; they have a bomber, I think the Mitsu-

bishi 97, which is said to look something

like a B-25.

‘We turned south to run down the coast |

before heading for China. And now our

main worry was about our gas supply. But

when we turned west again over the China

Sea, we ran into fog patches and squalls, and

the storm we were getting into kicked up a

35-mile-an-hour tail wind to help us along.

That made us feel better, although no’.

exactly good. It was still a_hit-or-miss

proposition. If the tail wind held, we knew |

we could probably make the China coast.

But what then? We were flying low to save |

fuel, but running into increasingly bad

patches of fog. That forced us up to 500 feet,

and kept us flying blind most of the time.

By dark we were completely blind, with |

no way of estimating drift or sighting on a

star. We had to go up to 7,000 feet to clear

a mountain range we knew was just back of

the coast. And farther inland we knew we'd

hit even higher mountains. Finally, with less

than an hour's fuel left, the pilot told us we

were going to have to bail out. I remember

we had a long discussion on whether to take

our musette bags or not. I took mine, and

also salvaged my pint of whisky.

It's funny what you'll think of at a time |

like that. I was bitterly regretting having

to leave the 15 cartons of cigarettes 1 had

bought aboard the carrier at 60 cents a

carton. Bain felt even worse. He preferred

cigars, and when he went out he had to

leave the first box of 10-cent cigars he had

ever been able to buy in his life, and he

never got to smoke even one of them.

Sergeant Bain jumped out first, and then I |

went through the bottom escape hatch. That

hatch looked awfully deep and black as I |

went out and I hesitated a minute, wonder-

ing whether to go head first or feet first. I |

finally went feet first and got a good bump

in the head. The next thing I knew I was

in the air and my chute was open. I shined

my flashlight and there was nothing below

me but air and fog. I never felt anything

50 lonesome; I really had the blues,

Just above the earth my light showed

water, and I thought it was the ocean. But

it was a rice paddy with a stream running

through it. 1 lit running, on both knees, and

got out of that parachute in nothing flat.

T pulled myself together and walked about

two miles to a tiny settlement, but found

that all the doors were barred and no one

would answer my knocking. It was raining

and I was wet and cold and miserable.

After what seemed like hours I found a

man and his wife and persuaded them (by

sign language) that they had nothing to

fear. They took me to their home, next to

a big Chinese temple, and called out the

whole family. A very old man took charge

then, but we still couldn't understand a

word of each other's language. They gave

me a place to sleep and offered me food, but

1 played safe and stuck to my own canteen

and emergency rations.

The next day a young boy not over 14—

guided me about 10 miles to a larger town

where a Chinese officer took me to a military

headquarters. I saw a flat map of the world

hanging on the wall, and pointed to the U.S.

and then to myself. They beamed and under-

stood that, all right. Later Lieutenant Macia

showed up, and the Chinese made signs to

show us there were three more. Our entire

crew was reassembled. Bain was the last to

come in. He had been knocked out landing

with his parachute and spent the night on a

mountain top.

We were all taken then to a big military

post where we had our first real meal in

China, with fried eggs, sweet sauce, bamboo

and bean sprouts, salt bread, and tea. We

thought it was a banquet, but it was nothing

compared to the luncheon General Ku later

gave us at Third War Area Headquarters:

They had 50 dishes, including a special treat

for us—the American dish, chop suey!

Later we were sent by train and bus to

a big air base built for the U. S. Army.

From there, one of our C-47 transport ships

flew us to Chungking. There we were told

that we had been awarded the Distinguished

Flying Cross. And at another luncheon

Mme. Chiang Kai-shek presented us with

the Chinese Army and Navy Air Force

Medal.

From China I was transferred to India

and from there later ordered back to the

United States. And the first thing I did

when I landed back in the good old U. S. A.

was to go out and mow down a couple Of

American T-bone steaks.

-

Autore secondario

-

Jacob Eierman (writer)

-

Fred Rodewald (illustrator)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1943-07

-

pagine

-

64-68

-

Diritti

-

Public Domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by

-

Matteo Ridolfi

-

Alberto Bordignon (Supervisor)

-

Copertura territoriale

-

Japan