-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

Detroit Moves into Your Home Town for Help in Building Guns to Smash the Axis

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Detroit Moves into Your Home Town for Help in Building Guns to Smash the Axis. Shops by the Thousands throughout Industrial America Feed Part to the Great Arsenal City

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

HIS war has so speeded up

and complicated our lives that

we tend more and more to do

our thinking and talking in

shorthand, in catch phrases.

“Pearl Harbor,” for instance,

has become a national symbol

for initial frustration, humilia-

tion, and determination to exact

satisfaction. And since Pearl

Harbor we have come to talk of

“Detroit” as a symbol for what

a punster might call conversion

and national salvation.

The Detroit we speak of is, of

course, the entire automotive

manufacturing industry, con-

verted to war production. But

unless we are careful, we are

likely to think of it as one city

— especially since censorship

frowns on the identification of

towns where munitions are made.

Actually, if you live anywhere

in the Northern industrial area

from east of the Alleghenies to

the Mississippi basin, the odds

are that some segment of De-

troit is in your own home town—fabricating

some precision part for a complex item that

will become merely part of a complex fight-

ing machine.

The city of Detroit is the nerve center,

the command post, of a vast, far-flung or-

ganization of brains and skill. It has become

even more so since, a few months ago, the

Army Ordnance Department at Washington

split off all its offices having to do with

tanks and transport equipment and set up

the Tank Automotive Center in Detroit with

a military and civilian personnel of 4,000.

But the command post is not the best

place to watch a war, and neither is one of

the big spectacular war plants the best

place to understand production. Close to

Detroit, for instance, is the Detroit Tank

Arsenal, as exciting a war-industry sight as

you might hope to see. Here are acres

of machines making transmission gears.

Through other acres the overhead cranes

lightly swing great cast tur-

rets and welded hulls from

station to station, while

workmen machine their pre-

cision parts. And on the

final assembly line there

suddenly appears, as if by

magic, a host of other parts

—guns, engines, tracks, and

all the secret inner workings of the turret.

It is an exciting experience to watch these

great, complex engines of war take shape

and roar off to the proving grounds; but you

can’t understand a river by looking at its

mouth. It was with some such thought in

mind that I recently got on a train in Detroit

and rode two hours to take a close look at

what they were doing at the Olds Works of

General Motors.

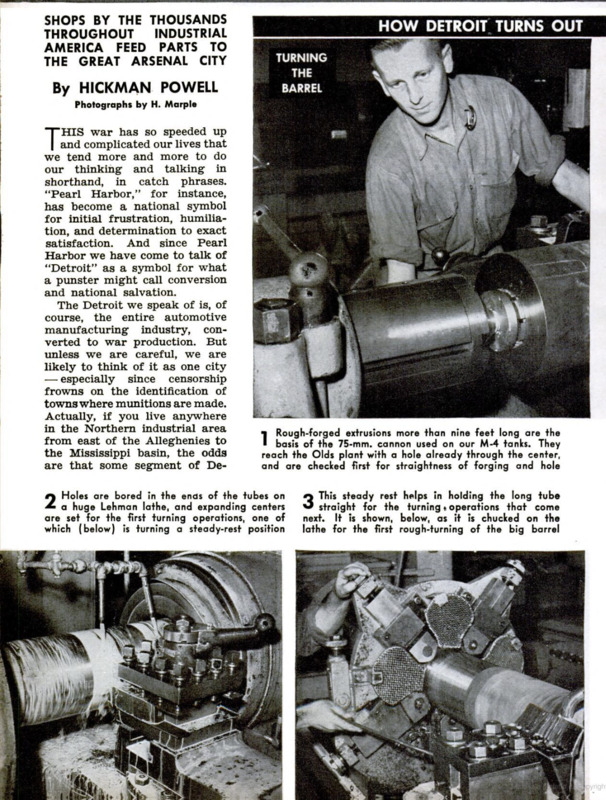

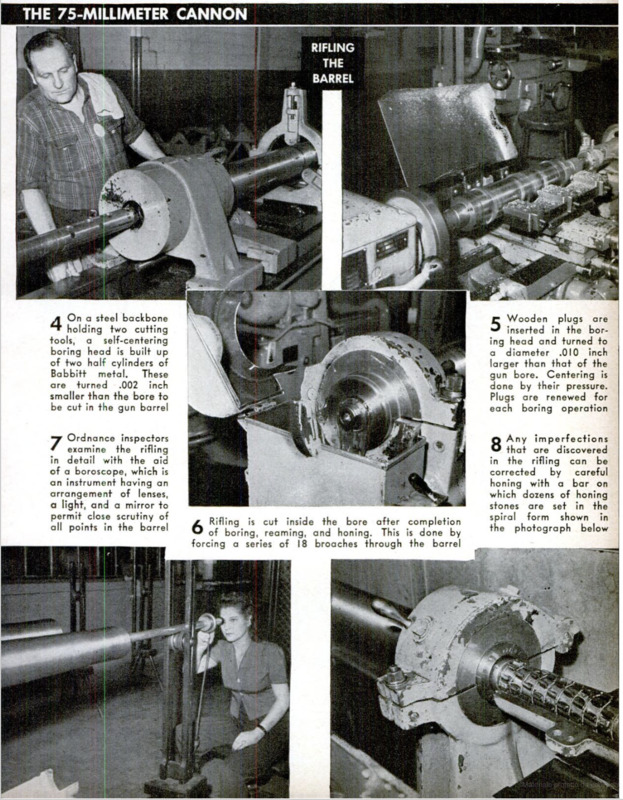

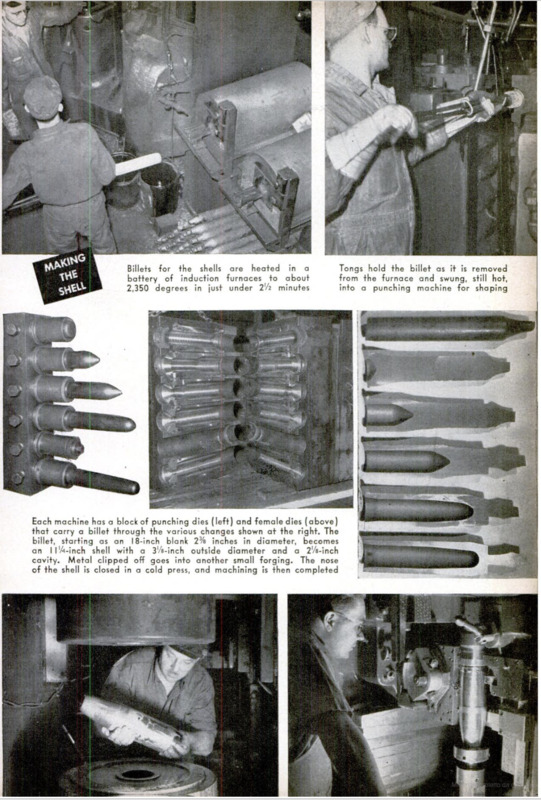

Olds is a specialist in weapons, in stings

for the hornet, and its various units cover

better than 100 acres. It makes shell casings

for the 75's and 105's by the millions. It

turns out a flood of 20-mm. cannon

for Mustangs and Spitfires, 37-mm.

cannon for Airacobras, and 75-mm.

guns for M-4 tanks. You get

some idea of the rate of production

from the continual, intermittent

roar of aircraft cannon in under-

ground testing tunnels.

Olds first got into war industry

in 1940, turning over its new No. 1

forge plant to the manufacture of

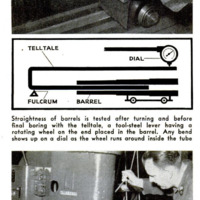

shells. As indicated in some of the

pictures accompanying this article,

this plant is itself something of a

marvel of mass production. Olds

was so successful that it is now op-

erating five great shell forges in

Michigan, Missouri, and Wisconsin,

turning out a fantastic number of

millions of projectiles. But forging

steel shells is a relatively simple

procedure. It was in the precision

work of making guns that Olds met

the real test.

In April, 1941, the Olds Works

first tackled the delicate art of the

gunsmith, and six months later, just

a few weeks before Pearl Harbor,

the first guns came off the assem-

bly line. They were the M-2 version

of the 20-mm. cannon, based on the

British Hispano Suiza, for installa-

tion in the leading edge of a pursuit

plane's wing. As automatic guns

£0, this is relatively simple, for it

needs no aiming mechanism; but

its 115 pounds of steel include 127

parts, each of which must be ma-

chined to the gnat's eyebrow. It

must fire a burst at an average of

600 rounds a minute, and never jam.

To machine that many parts in

mass production would have taken

a vast new plant if Olds had tackled

the job alone. Instead, the company

called in 500 representatives of out-

side shops, showed them blueprints,

specifications, and models of the

127 parts, and asked them what

they could make. The upshot was

that 124 of the 127 parts were

farmed out to other shops—many

of which had never tackled any-

thing so precise and complex be-

fore. Olds set up trouble-shooting

teams of technical and production

men and

sent them from plant to plant to teach

simplified methods for intricate jobs.

“Subcontracting is the auto industry's

middle name,” said S. E. Skinner, general

manager. “We at Olds have made it our

first name as well. Our results have been

excellent and our problems have been no

greater than those we normally encounter

in making automobiles.”

There were problems, of course, some of

them with their humorous aspects. One of

the most difficult subcontracts, involving a

tolerance of only one half of one thousandth

of an inch, was given to a thoroughly compe-

tent tool-making shop in Detroit. When the

parts were delivered, the inspectors found

them more than a thousandth off gauge.

Olds protested. The toolmakers insisted

they were right. But the next delivery

again was off. Belligerently Olds engineers

put the offending parts in a car, took along

their inspection gauges, and drove to De-

troit. Arriving at noon, they went to lunch

with the subcontractor, then returned to

the shop to demonstrate that the parts were

entirely off specifications. Much to their

amazement, when they applied the gauges,

the parts were practically perfect. During

the lunch hour they had lost the chill ac-

quired in transportation from plant to plant.

It was a part that will vary by three thou-

sandths merely from body heat.

Hardly had Olds got under way with |

20-mm. production before Pearl Harbor

changed everything. At Olds, as elsewhere,

automobile production lines were scrapped.

Olds took contracts for 37-mm, and 75-mm.

guns, converted some machinery, brought

in hundreds of new lathes, broaches, and

other precision machines. All its acres are

given over to the turning and assembly of

war's barking tubes of death. But still the

subcontracting technique holds true. On

each of its three major jobs, Olds itself man-

ufactures only three parts.

Take the 87, for instance. Olds makes the

barrel, the tube extension, and the lock

frame. The other parts are made by 68 sub-

contractors in shops scattered over 35 cities

and towns in 10 states of the East and

Middle West. And only 18 of those 68 sub-

contractors were doing business with Olds

in the days of automobile manufacture.

Multiply that by a few thousand times,

remembering that one type of gun is only

one small item among all the infinite variety

of jobs that go to make a plane, a tank, or

any of the other engines of war. The trun-

nion block of the 37-mm. gun, which must

be held within .0005 inch, is being made by a

company that used to make package ma-

chinery for the canning industry.

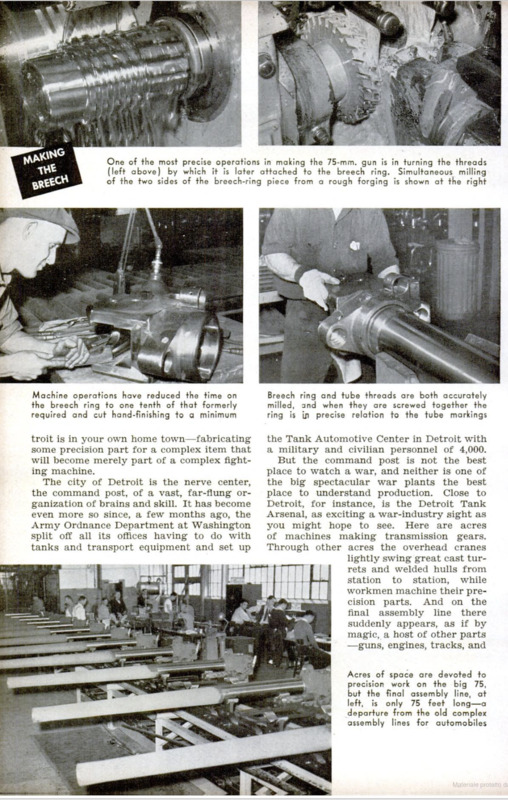

The acres of floor space at Olds devoted

to making 75-mm. guns had been, in 1941,

a vast assembly line, where men were

putting on wheels, tightening nuts, fitting

fenders—all the partly skilled jobs that auto-

mobile production involves. But today the

assembly line for the 75 gun is only 75 feet

long. Joe Smith, who in 1941 was tighten-

ing tire lugs, today is running a broaching

machine that cuts out the insides of a breech

ring in one tenth of the time it used to take.

Joe Doakes, who used to do rough sheet

metal work, today is doing the delicate ma-

chining of a powder chamber.

There always was precision work in mak-

ing the engines and running gear of auto-

mobiles, but today that precision work and

the number of precision workers have been

multiplied—not only in the main war plants,

but also in thousands of small-town parts

factories. And in the same way, techniques

of management, tricks of production, and

hidden secrets of metallurgy have been

spread through America at a rate we could

not have imagined five years ago.

And while production skills thus multiply

in the gun factory, at a building near by

hundreds of soldiers and sailors every three

weeks are learning the intricate skills of

maintaining the guns, taking them apart

and putting them together blindfolded—

just as thousands of other military men in

other schools are learning the intimacies of

airplane and tank engines and all the other

complex instruments of war. Before the

war America led the world in number of

skilled mechanics. We will have millions

more of better ones after the war.

Bill White, screwing on nuts, never knew

he could run a lathe. Farmer Jones's son

never knew he could doctor an airplane en-

gine. The small town manufacturer never

knew he could make as good a gun part as

the next fellow. The symbolic Detroit sus-

pected, but it did not really know, that it

could convert itself overnight into an in-

vincible armament industry—that it was a

method of organization, planning, and teach-

ing, able to lick any production job.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Hickman Powell (writer)

-

H. Marple (photographer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1943-07

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

104-108, 198, 200

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public Domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Matteo Ridolfi

-

Alberto Bordignon (Supervisor)

Popular Science Monthly, v. 143, n. 1, 1943

Popular Science Monthly, v. 143, n. 1, 1943