-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

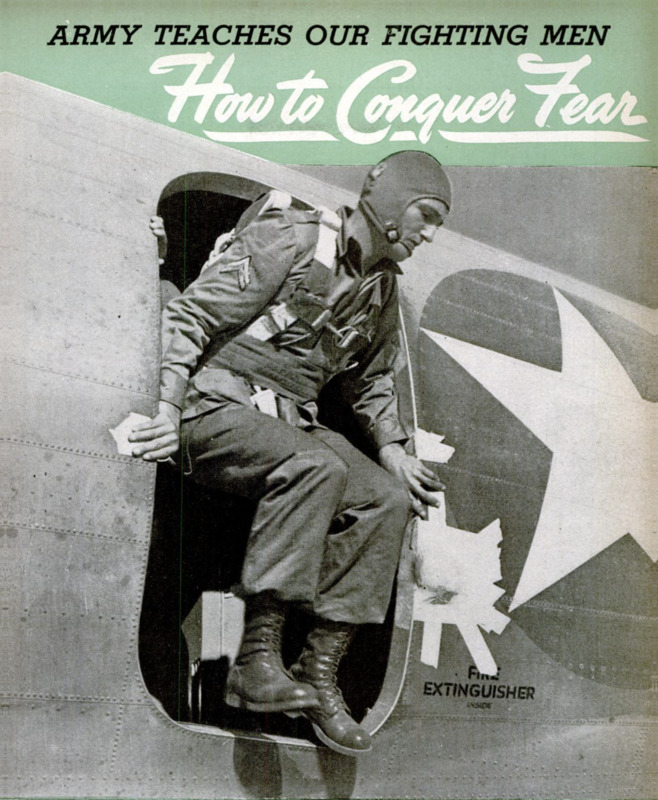

Army Teaches Our Fighting Men How to Conquer Fear

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Army Teaches Our Fighting Men How to Conquer Fear

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

WAR is a frightening occupation for

our soldiers. On every front they

must be prepared not only to take what the

enemy has in the way of terror, but to dish

it out in bigger and stronger doses. It's a

fearsome job for young men whose nearest

approach to violence once was to shout,

“Kill the umpire!”

But great camouflaged transports are

carrying these young men in increasing

numbers to the war zones. Many already

have passed months in battle sectors where

all the furies of modern warfare rage.

Blasting, strafing dive-bombers have howled

out of a foreign sun to slice the air over

their foxholes. Unholy screams of wings

and motors and bombs have torn at their

eardrums. Shattered rocks and flying stone

have added to the threat of shrapnel. They

have known lack of food and water, the

tenseness of the zero hour, the sight of

friends and comrades being killed and

wounded before their eyes.

These former bookkeepers, clerks, farm-

ers, and factory hands are being exposed

to all the horrors of war. It makes little

difference what outfit they're with—in-

fantry, tanks, tank-busters, air forces, para-

troops, engineers—they feel the fury of it.

Some have cracked under the terrific strain.

Authentic reports show that nearly one

third of the first casualties shipped back

were mental and nervous cases. But the

fight goes on, with veterans, replacements,

and fresh troops carrying the battle to the

enemy.

Army officers are confident that our men

have the stuff needed for victory. Some of

that confidence stems from the belief that

our soldiers have the finest and most mod-

ern equipment in the world; some comes

from the knowledge that they are excel-

lently trained, know how to use their weap-

ons; some springs from proof of their great

physical stamina, and some comes from the

historical fact that American soldiers have

yet to lose a war. But a factor not to be

overlooked is the Army's remarkable new

program to combat fear and mental in-

stability. For this is responsible to a large

degree for our success in turning millions

of civilians into first-class fighting men.

From induction centers to training camps

to battle areas, our soldiers are feeling the

effects of the program. It's helping them to

withstand the pressure of Army life on

minds, nerves, and emotions. It's assisting

them to be competent, dependable, coura-

geous; and it's untangling minds that have

become twisted by the stresses of war. This

is the first time that such an effort has been

made on a large scale.

Employed only in rudimentary form late

in World War I, the process was started

last year with the creation of a neuro-

psychiatric branch in the Surgeon General's

Office in Washington. Then followed the

opening of a unique school in Lawsen Gen-

eral Hospital, Atlanta, Ga., in which in 196

hours of classes young Medical Corps offi-

cers are being fitted for the special service.

Selected with great care by Col. Roy D.

Halloran, chief of the wranch, and ranking

Medical Corps psychiatrists, they are as-

signed after graduation to one of the nine

Army commands in this country. Later,

when they are sent abroad, they work under

the direction of the mew neuropsychiatric

centers established in the European and

South Pacific theaters.

Personnel and morale officers, chaplains,

and field officers assist the psychiatrists in

the program. Never before has there been

such co-ordination of effort to improve sol-

diering and make it more palatable. The

psychiatrists not only watch and help in-

dividual soldiers, but they seek to create

conditions wherein the stresses are mini-

mized. They help devise means of relaxation

and entertainment. They live with the

troops, experience their difficulties, and help

to solve them. Colonel Halloran says of

them: “They are specially trained medical

confidants, with a real desire and ability to

help.”

But even more than that, these new

friends of our soldiers stand as a safeguard

against one of the worst tragedies of battle

—the thousands of war-induced mental

cases that usually occur. For from the

gateway to the Army, where an average of

seven out of every 100 men up for induc-

tion are screened out as mentally unstable,

to the point of embarkation, those Who

show tendencies to crack are sent back to

their homes. In peaceful surroundings,

those rejected men can live

normal lives and prove an

asset rather than a liability

to our war effort.

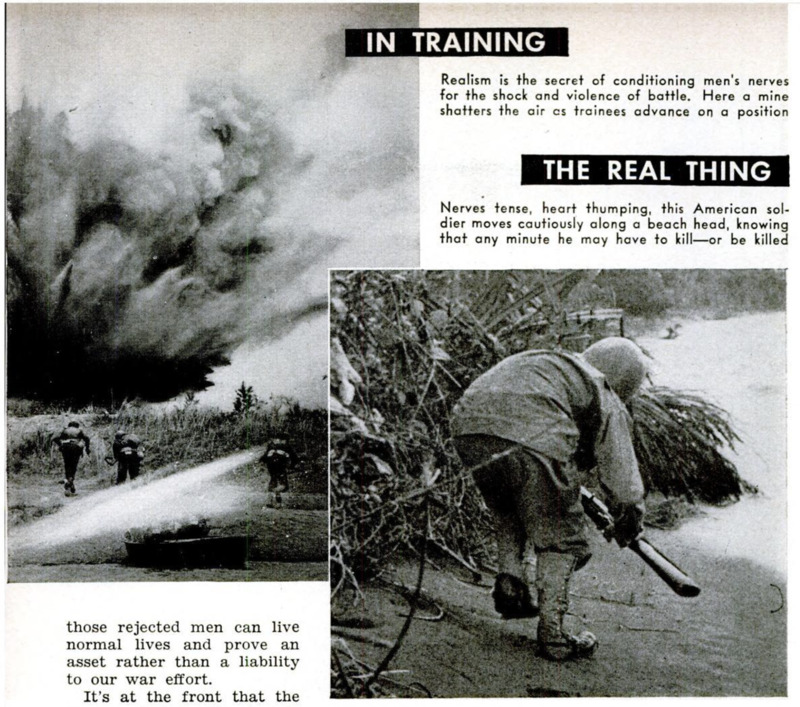

It's at the front that the

supreme test for the Army's

program comes. That's the scene for the

all-out fight against fear. By that time the

soldier has learned many things about the

science of war and wants to use that

knowledge to blast the enemy. But his

eagerness is mixed with dread and fright.

The first time he goes into battle, he's apt

to be downright scared. His throat becomes

dry; his stomach feels like flipping, and his

heart does a dance macabre under his khaki

tunic. And that may be true every time he

gets within striking distance of the enemy

But he must learn to control his fear.

Experience has shown that fewer sol-

diers go to pieces in outfits with good mo-

rale, in winning outfits, and in well-trained

outfits. It's the psychiatrists’ job to main-

tain confidence. They know that men under

fire or about to go under fire want facts,

not psychiatric patter. So their tactic is

to discuss fear frankly, stressing the fact

that to be scared is a normal reaction

shared by veterans and green troops alike—

not a sign of cowardice.

Fear, as demoralizing and uncomfortable

as it may be, actually is the body's prepara-

tion for action. The heart beats faster,

pumping blood to the arms, legs, and brain

where oxygen is needed. Quickened breath-

ing is the part cf the lungs. Blood pressure

goes up, and adrenalin, nature's “shot in

the arm,” pours liberally into the blood

stream. Sugar is released as fuel for the

human fighting machine.

That's the normal reaction during the

frightening moments just before an attack.

Sometimes the soldier feels stunned and

paralyzed, and has difficulty getting started

into battle. But the Army's program of

training and discipline comes to his aid,

and it becomes second nature to obey com-

mands and carry out his own job. That's

why there is so much importance attached

to keeping fear under cantrol—conquering it.

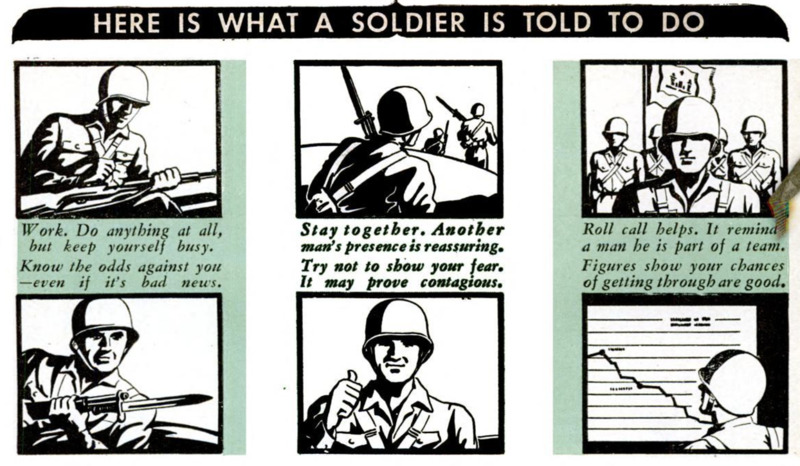

The Army has six ways to fight fear. For

men facing that greatest period of tense-

ness—just before the zero hour—the slogan

is: “Work—do anything—but keep busy.”

Action relieves stress on minds and nerves.

Troops under fire should keep in contact

with comrades, if that is at all possible.

Just the presence of another r:an mot far

off helps quiet fear.

Calling the roll is helpful. It reminds the

men that they are part of a close-knit or-

ganization, not facing the dangers alone.

Great reassurance comes with knowledge

that every man is in his place, despite the

smoke and din of battle, and resistance to

fright mounts.

Another important remedy against fear,

strange as it seems, is to keep soldiers in-

formed of the odds confronting them. Offi-

cers are urged to keep in mind that knowl-

edge is power over fear. Men posted on the

dangers, the kind of weapons they're up

against, and the size of the enemy's force

are far less susceptible to fear.

Soldiers are taught that to be afraid

doesn’t mean they must act afraid. Since

fear is contagious when it is expressed by

action, men who become panicky must be

removed from the sight of other men. It

is the soldier's responsibility to control

signs of his own fear if he can, so as to

spare his comrades. Fighting men have

learned that the very effort often reduces

fear and brings calmness.

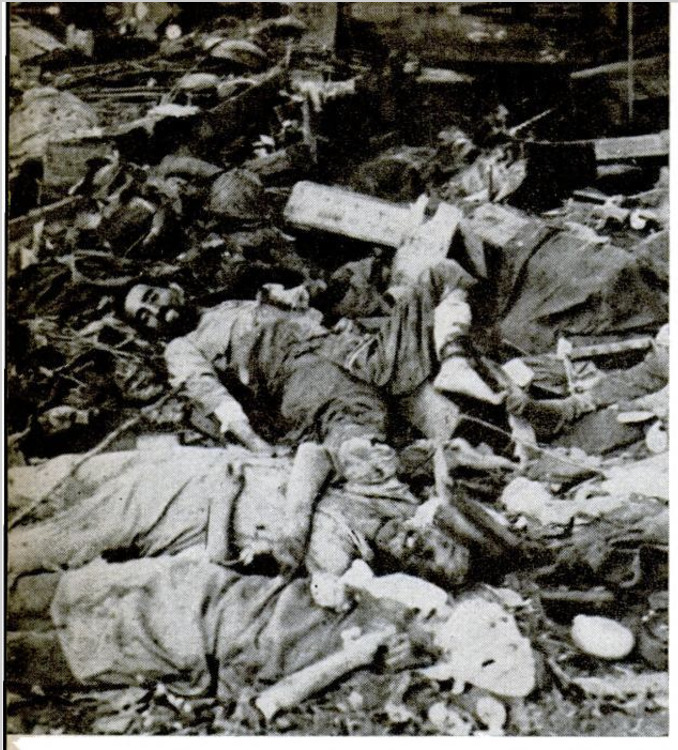

Soldiers are acquainted with statistics

on the percentage of casualties in action.

That is reassuring. For, according to fig-

ures on even the bitterest fights, compara-

tively few men are killed, and the chances

that any one man will be among the fatally

wounded in any one battle are relatively

small.

The Army knows that courage and fear

are not opposites—that they may be pos-

sessed by a soldier at the same time. But

the soldier who has courage need not worry

about his feeling of fright. He'll keep that

under control. In the words of the National

Research Council: “None but the brave can

afford fear.”

In talks that I have had with some of

our wounded soldiers brought back from the

war zones for treatment in the Army's great

Walter Reed Hospital, in Washington, it

was interesting to note how few admitted

having experienced fear. One chap, who has

been decorated with the Silver Star for dis-

tinguished service in North Africa, summed

it up by saying: “Hell, we were too busy to

get scared.” His ritation said that, although

painfully wounded, he had pushed forward,

causing enemy gunners to fire upon him and

reveal their position, bringing about their

defeat.

This 22-year-old veteran said, however,

that he and his comrades experienced a few

“uneasy moments” ns they were waiting

orders to start the invasion. He said they

showed it In funny ways. For instance, one

soldier cleaned and recleaned his rifle. An-

other looked at his watch every few seconds,

and a third couldn't seem to satisfy himself

that his gun was loaded, checking it a dozen

or so times.

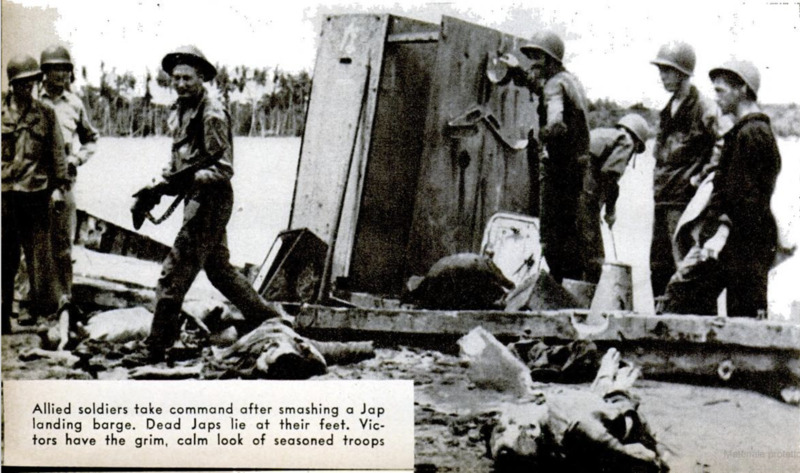

Our young hero and his comrades may

have been scared stiff, but they had learned

that secret trademark of a good soldier—

fear control. The magnificent thing I ran

onto was the universal eagerness of the

wounded to get back in the fight. They

seemed to resent the fact that the boys with

whom they went overseas were stil in the

thick of things, while they were forced to

“loaf in & hospital.” The Army's program

has sold them on the idea that Army life,

despite its hazards, is not so frightening.

That “salesmanship” is significant. For

the success of neuropsychiatry is measured

by the number of soldiers kept in the Army

not by the number eliminated. Is axio-

matic that many of war's greatest exploits

are achieved by veterans who have returned

to the fight after their wounds have healed.

Other valuable contributions have been

chalked up by men whose first maladjust-

ments might have wrecked their Army

careers had they not been corrected. Take

the case of fellows who develop Jitters while

on training maneuvers. These same soldiers

have been transformed into first-rate cooks,

‘mechanics, and bullders who have a vital

part to play in winning the war.

Those who are being shipped back from

North Africa and the South Pacific as

mental and nervous cases benefit greatly

from the program. The neuropsychiatrists

Who treat them are experienced in straight-

ening minds. They know that these casual-

ties are not insane—that with proper treat.

ment they will respond in a locale that has

Done of the dangers and fury of the fighting

fronts. The trouble in most cases is that

these men came from obscure little grooves

in civil life, and their minds slipped when

they came ‘up against the rigors of war.

Most of them will be able to return to the

lite they lett.

As in the case of men awaiting the zero

hour, the psychiatrists recommend that the

‘meurotics be kept busy. So at Walter Reed

and the other great Army hospitals you find

them deeply engrossed in occupational ther-

apy. Some make belts, ship models, chess.

men; others knit or embroider. A few

skilled in the arts are kept occupied with

paintbrush and clay. With their hands busy,

their minds have less chance of groping and

strength of thought and direction seeps

back.

Looking ahead to the period immediately

after the war, the neuropsychiatrists appear

slated for work equally as important as that

In which they are now engaged. For they

alone know the things about the returning

soldiers that will make it possible to fit them

back into civilian life. As they now are

helping soldiers out of unhappy situations

into niches that make soldiering endurable,

they will be able to guide the veterans to

happier ground. Having come from civilian

lice themselves, the psychiatrists will them-

Selves return to it, and there continue to give

advice and aid to the men whom they helped

to lick fear and the enemy.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Jack O'Brine (writer)

-

Signal corps photo (photos)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1943-08

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

49-53

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public Domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Matteo Ridolfi

-

Alberto Bordignon (Supervisor)

Popular Science Monthly, v. 143, n. 2, 1943

Popular Science Monthly, v. 143, n. 2, 1943