-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

Aircraft carriers explained

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Title: The flat-top carries on

-

Subtitle: Test of battle shows its place in naval warfare

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

SHORTLY before her gallant end in the Far East, the U. S. aircraft

carrier Leaington experienced one of the strangest of wartime ad-

Ventures. Nine bombers, appearing out of thickening dusk, maneuvered as

for a normal landing. But all of the Lexington’s bombers were aboard and

accounted for. Suspicion turned to certainty when an American scout

plane in the air opened fire on the strangers. They were Japs, who had

mistaken our carrier for one of their own. Discovering their error, they

hastily turned tail. Some of the Lezington’s crew still think it would

have been fun to let them land.

Perhaps such a fantastic incident could happen only aboard a carrier—

a kind of ship that is rewriting the rules of naval strategy. Lightly armed

and armored, its real “artillery” consists of dive bombers, torpedo bombers,

and fighter escorts, which give it about 20 times the striking range of

the most powerful naval guns, For “armor” it depends mainly upon its

own fighting aircraft, Tested for the first time in this war, it has proved

capable of missions that its designers never dreamed of.

Originally, carriers were intended to supplement surface forces in major

fleet actions. A concession to the growing importance of air power, they

would remain safely guarded in the rear while their planes neutralized

enemy air forces and left the decision, as always, to the mighty battle

wagons of the sea.

It took Pearl Harbor to show us what else our carriers could do. All our

naval tradition called for attack—but with what? Every surviving battle-

ship of our Pacific Fleet lay temporarily disabled at Hawall. So we flung

against Japan our ace in the hole, our fleet of seven aircraft carriers.

Task forces of cruiser-escorted carriers raided Jap-occupied Marshall

and Gilbert Islands, Wake Island, and the Marcus Islands. Perhaps the

actual damage done had little more than nuisance value. Far more im-

portant, we were testing a bold new technique in naval warfare. We found

that our carrier forces could pinch-hit for capital ships. Moving swiftly

under cover of airplane reconnaissance, and of rain squalls and overcasts,

they could be projected anywhere upon the high seas—even deep into

regions supposedly controlled by the Japanese.

Then came blows that really hurt. American carrier raids on the Jap

bases of Salamaua and Lae, in New Guinea, sank 20 ships and delayed Nip-

ponese plans to advance southward for two months. At Tulagi Harbor in

the Solomon Islands, our carrier planes surprised another invasion fleet

and practically annihilated it.

In the Battle of the Coral Sea, the memorable radio flash “Scratch one flat-

top” announced the sinking of Japan's big new carrier Ryukaku—demolished

in a few minutes by 25 bomb and torpedo hits from U. S. carrier aircrat.

The Battle of Midway shattered a Japanese armada bent on seizing that

strategic island—*“unquestionably in preparation for an attack on Hawaii,

and, perhaps, even an assault on continental United States,” declares

Secretary of the Navy Knox. Working in close co-operation, the Navy's

carrier planes and the Army's Flying Fortresses sent four Jap carriers to

the bottom of the sea.

By the time that U. S. battleships reappeared in the news, during the

series of naval engagements off Guadalcanal Island, our carriers already

had definitely stemmed the tide of Japanese conquest. Naturally our

losses had been heavy—but so were the enemy's.

Of the 14 carriers, many built secretly,

that Japan now is believed to have possessed,

the U. S. Navy currently reports the follow-

ing disposition: six sunk, one probably sunk,

and seven damaged. Taking into account

the Navy's reputation for ultra-conservative

claims, the actual score may be considerably

higher. Perhaps this accounts for the dis-

astrous absence of Japanese carriers in the

major battle of Guadalcanal last mid-

November—a smashing American naval

victory—and in the battle of the Bismarck

Sea, last March, when an entire Jap convoy

of ten warships and twelve transports was

destroyed from the air.

As to our own carriers, we retain three of

our original seven, at this writing—the

33,000-ton Saratoga, sister ship of the lost

Lexington; the 20,000-ton Enterprise, sister

ship of the lost Yorktown and Hornet; and

the 14,500-ton Ranger, comparable in size

to the lost 14,700-ton Wasp. With our vastly

superior shipbuilding facilities, we have been

replacing our losses so rapidly that Japan

can never again hope to catch up with our

carrier strength.

If headline readers puzzle over how many

new carriers we are putting into the water,

they can hardly be blamed. For the Navy

is building or converting no less than four

distinct types.

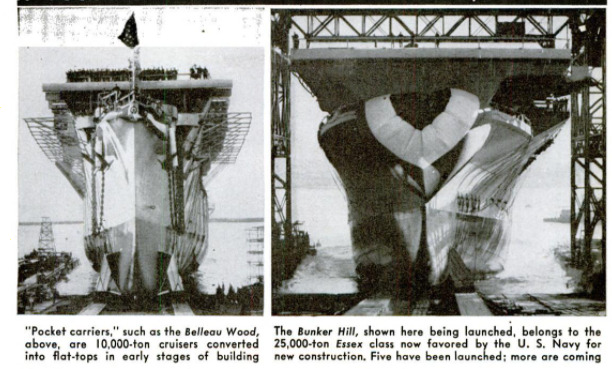

Big 25,000-ton vessels of the new Essex

class now represent the Navy's preference

for standard fighting carriers. Their excess

of displacement over the previous 20,000-

ton Hornet class may be used to increase

cruising range by adding fuel-storage ca-

pacity—an important advantage in operat-

ing far from home bases. Five of these

ships have already been launched—the

Essex, a new Lexington, the Bunker Hill,

a new Yorktown, and the Intrepid. By the

time these words are read, the first two will

probably have been completed; and the

second two should be at least near comple-

tion. Many more are building, in a vast

construction program that is altering our

carrier strength almost from day to day.

“Pocket carriers” of the Independence class,

combat ships converted from 10,000-ton

cruisers in early stages of construction, are

probably the most controversial type among

newcomers to our Navy. Critics declare that

we need cruisers too badly to transform

them into carriers. Limited size, they point

out, reduces the small ships’ usefulness as

carriers, and rough seas would make take-

offs and landings hazardous. Advocates of

the pocket carriers counter with the asser-

tion that carriers now perform scouting,

raiding, and fighting missions as well as

cruisers do. Japanese carriers just as small,

some equipped with anti-rolling gyro

stabilizers, have been successfully

operated. Limited size may be prefer-

able to “putting too many eggs in one

basket”; war lessons have not even

yet demonstrated the ideal dimensions

of a carrier, and we will be playing

safe by building small ones as well as

large ones. The midget craft can use

smaller and shallower harbors. Final-

Ily—and this is the compelling argu-

‘ment—we need quickly all the combat

carriers we can get, and the pocket

variety pan be rushed into service

while big ones, which take longer to

build, are still on the ways. Therefore,

former cruisers launched as aircraft

carriers include the Independence,

Princeton, Belleau Wood, Cowpens,

Monterey, and Cabot. At least the

first of these should now be ready,

with the others following in rapid

‘succession.

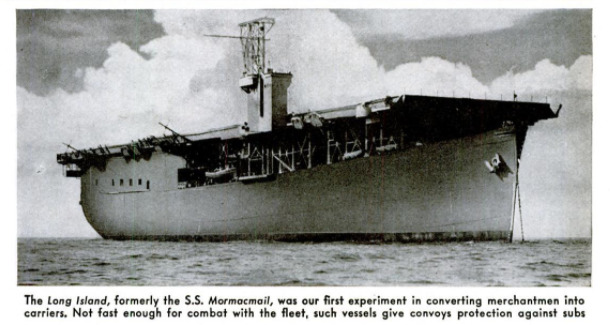

Following the Navy's successful ex-

periment in converting the former

merchantman Mormacmail into the

U. 8. carrier Long Island, in 1941, dozens of

similar vessels have been placed in operation,

according to Secretary Knox. Because of

their limited speed, none of these ships are

intended for combat duty. They serve ex-

cellently, however, to escort lumbering con-

voys, using thelr planes to spot and destroy

enemy submarines—and releasing fast de-

stroyers for other urgent missions. Con-

verted merchant ships, or aircraft carriers

built on the same lines, also may be used

as “ferries” to transport other planes than

their own. Uncrated, and ready for im-

mediate action, a cargo of short-range

fighter planes can be flown off the deck to

its destination. Modern aircraft engines,

approaching 2,000 horsepower, compensate

for the restricted length of the take-off run.

Successful experiments have also been re-

ported with catapulting mechanism of special

design. Scores of the “Woolworth carriers,”

as the British have nicknamed them, are in

production.

To teach personnel how to man the mighty

carrier fleet we are building, the Navy has

placed special training carriers into service.

Two of them, the Wolverine and the Sable,

have the distinction of being the world’s

only side-wheeler aircraft carriers. They

are operated on the Great Lakes, where

they once were excursion boats.

Suppose a raw recruit sets out to learn

everything from the ABC's to the fine points

in the design and tactics of aircraft carriers.

Here are some of the things he finds out:

Because of its dual function as a warship

and as a floating airport, a standard carrier

has a complement of 2,000 to 3,000 officers

and men—more than serve aboard any other

man-of-war. Its mighty power plant drives

it through the seas at higher speed than

that of any but a few of the most up-to-date

destroyers. The world’s largest carrier at

this writing—the 888-foot, 33,000-ton U.S. S.

Saratoga—greatly exceeds the length of a

battleship of our new North Carolina class,

and nearly matches it in tonnage. “Fire

power” of an

aircraft carrier depends largely upon the

number of planes it can operate. Large U. S.

carriers, including the Essez class, employ

about 80 planes apiece—considerably more

than the biggest carriers of foreign powers,

and about twice as many as our “pocket

carriers” and converted merchantmen.

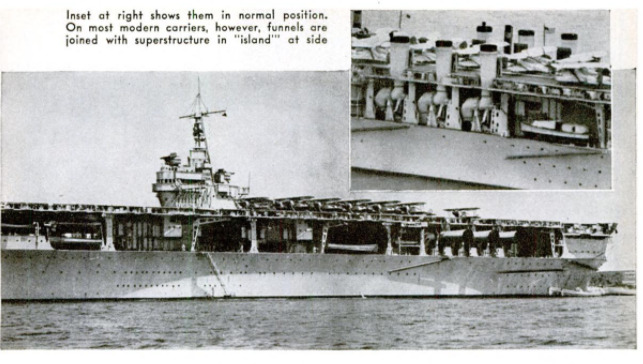

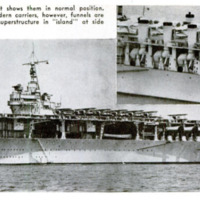

A novices first glimpse of an aircraft

carrier centers upon its most distinctive

feature—its great flat top, the flight deck

where its planes soar aloft and land. To

keep this space clear of obstructions and

free from turbulent, hot gases from the

funnels, curious expedients have been tried.

The USS. Ranger was built with three

stacks on each side, arranged to swivel 50

that they could be swung horizontally out-

board during flight-deck operations. Some

Japanese carriers employ variations of the

scheme. Most modern carriers, however,

combine the funnels with the superstructure

in an “island” at the side of the ship.

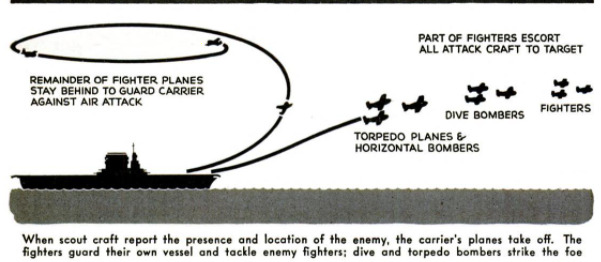

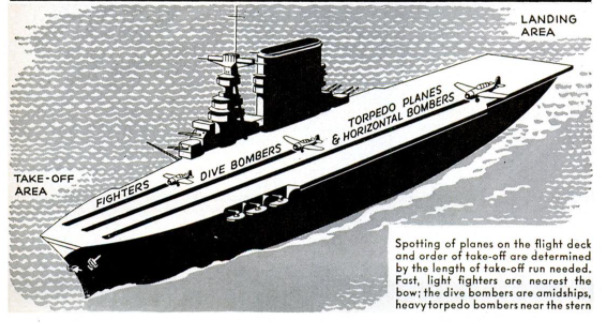

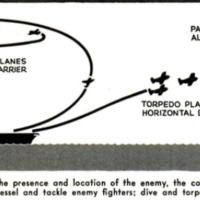

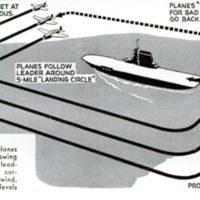

Before dawn, on sea duty, giant elevators

bring planes up to the flight deck from the

hangar deck below. The planes are spotted

on the deck in the order of the take-off run

they require—fighters nearest the bow; dive

bombers (which double as scouts) amid-

ships; torpedo bombers, armed with tor-

pedoes or with heavy bombs, toward the

stern. Heaviest of the carrier's planes, they

need most of the length of the deck to get

into the air.

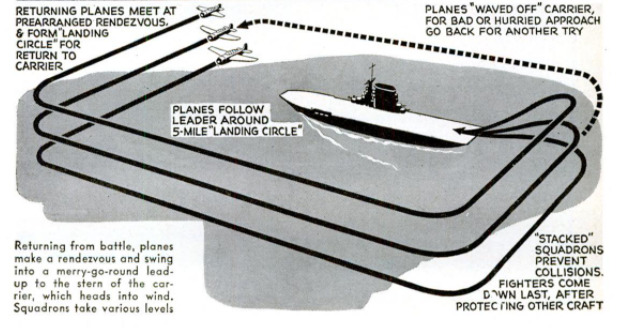

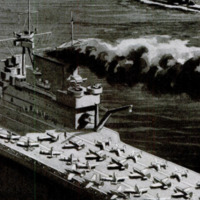

‘This is action, not a routine patrol, as

the commanding officer has explained to

squadron leaders the evening before. All

night long, the carrier's turbines have been

driving the high-speed ship toward the ob-

jective, which at 5 a.m. is 160 miles away—

direction, E.N.E. The planes are to attack

two cruisers in a harbor, and to destroy

shore installations.

Coffee in the ready room. Above the roar

of motors warming up, the “bull horn" or

ship's loudspeaker booms final orders. One

after another, the planes smoothly take off

and form into squadrons.

Over their low-powered interplane radios,

pilots converse as they approach and attack

the target, using fanciful nicknames to

identify their combat teams. Back in the

carrier's radio room, powerful amplifiers

pick up a running account of the fight.

“Margie to Jean, Cruisers sighted near

west cape.”

“Margie acknowledged. Will take nearest

cruiser.”

“OK. Jean. Far ship ours. Lona getting

fuel tanks.”

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Alden P. Armagnac (Article Writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1943-08

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

110-117, 212

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public Domain (Google Digitized)

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Matteo Ridolfi

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Popular Science Monthly, v. 143, n. 2, 1943

Popular Science Monthly, v. 143, n. 2, 1943

Schermata 2022-03-04 alle 15.03.32.png

Schermata 2022-03-04 alle 15.03.32.png Schermata 2022-03-04 alle 15.03.39.png

Schermata 2022-03-04 alle 15.03.39.png Schermata 2022-03-04 alle 15.03.47.png

Schermata 2022-03-04 alle 15.03.47.png Schermata 2022-03-04 alle 15.03.53.png

Schermata 2022-03-04 alle 15.03.53.png Schermata 2022-03-04 alle 15.04.02.png

Schermata 2022-03-04 alle 15.04.02.png Schermata 2022-03-04 alle 15.04.11.png

Schermata 2022-03-04 alle 15.04.11.png Schermata 2022-03-04 alle 15.04.18.png

Schermata 2022-03-04 alle 15.04.18.png Schermata 2022-03-04 alle 15.04.26.png

Schermata 2022-03-04 alle 15.04.26.png