-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

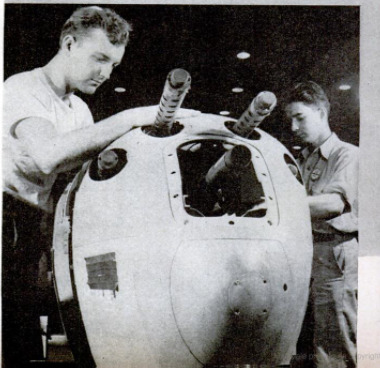

New guns for planes

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Flying gun carriers

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

TOMORROW'S decisive air battles

will be won by toughly armored fly-

ing gun carriers packing a weight of

fire power far greater than that of the

most gun-bristling fighter planes of

today.

Aircraft designers and builders of all

the major powers are engaged in a

breakneck industrial race, trying to

satisfy the armed forces’ insatiable de-

mands for stronger, better-protected planes,

and heavier, more destructive guns to

mount in them. Some types of planes al-

ready are firing projectiles powerful enough

to smash light tanks and motor transport.

Bigger guns are being tried out experiment-

ally, and some students of ordnance predict

the emergence of an air-cruiser type armed

with guns of three-inch caliber or larger,

possibly embodying rocket principles or

some other means of fire capable of over-

coming the serious problem of recoil.

In short, the science of aircraft arma-

ment, born in the First World War and

more or less stagnant in the 20 years that

followed, is now moving ahead again at full

speed under the insistent pressure of a big-

ger and tougher war.

Even in this air-minded day, few

Americans realize how greatly air-

plane fire power has been boosted.

The one-place fighter plane offers a

good basis of comparison. By 1918,

in the closing period of the war, both

sides had settled on a main fighter

type armed with two rifle-caliber

machine guns attached to the fuse-

lage and fitted with synchronizers

enabling them to fire through the

propeller arc without damaging the

blades.

With that armament a pilot who

managed to line up an enemy in his

sights for a reasonable burst-—say

five seconds—could pepper the foe

with about 166 bullets having a to-

tal weight of four pounds. Just be-

fore the outbreak of this war the

most heavily armed fighter plane in

service was the British Hurricane,

with eight .303 caliber machine guns

firing from the wings. The same

five-second burst from these ships

delivered around 800 bullets, weigh-

ing 20 pounds—or 400 percent more weight.

One of the most heavily gunned planes on

fighter duty in Europe today is the Royal

Air Force's Spitfire IX, which goes into ac-

tion with four .303 caliber machine guns

and two 20-mm. automatic cannon spitting

lead, steel, high explosive, and destruction.

In five seconds the ship can fire 400 ma-

chine-gun bullets and 120 20-mm. armor-

piercing or high-explosive shells. The total

weight of the blast runs around 45 pounds

more than eleven times that of the 1918

plane.

That kind of development in fire power is

the logical outcome of a corresponding de-

velopment in the armor protection of the

bombers which are the fighter's natural

enemy and prey. The rise of air warfare

has brought about a repetition in this field

of the long-standing race between ordnance

and armor plate in naval design. As usual,

gun power seems to have the edge, yet the

ability of some new bombers, especially the

American heavy types, to absorb punish-

ment and shoot back has proved a painful

shock to many an overconfident Axis fight-

er pilot.

The first military aircraft were not armed

at all. The top commanders in 1914 re-

garded their planes as observation devices,

somewhat more mobile than captive bal-

loons but no more aggressive. Individual

pilots took the initiative by carrying car-

bines, pistols, or shotguns aloft and potting

away at enemy ships that ventured within

range.

The next step was to mount a light ma-

chine gun on the ship, and the simplest ar-

rangement was to have the gun on a swivel

to be operated by the gunner in a two-place

plane. But single-seater ships had far

greater speed and maneuverability, so it

was clear that the ideal fighter would be

one in which the pilot could do his own

shooting, aiming the entire plane at the

target and firing the fixed gun by

remote control.

A gun bolted to the center of the

upper wing could fire above the pro-

peller arc, but it created wind re-

sistance and forced the pilot to stand

up if he had to clear a jam or change

ammunition pans. This arrangement.

was superseded by the development

of the first practical synchronizer

by Anthony Fokker, Dutch aircraft

‘manufacturer.

Fokker's device consisted of a

cam mechanism placed between the

airplane engine and the machine

gun's action. It was a tricky, cranky

gadget, but when lined up and ad-

justed with loving care it worked,

by restricting the gun's discharge

to the brief instants when the pro-

peller blades were in a horizontal

position and out of the line of fire.

The Germans had the inside track

on Fokker's invention and enjoyed a

brief advantage—until British and

French engineers duplicated the de-

vice.

Both sides continued to experi-

ment with new ideas in aircraft

weapons, but the synchronizer was

the only development that really

made itself felt in actual combat. All efforts

to mount heavier guns, for example, were

inconclusive. The British started work on

an automatic one-pounder cannon, but the

war was over before much progress had

been made with the design. In 1917 the

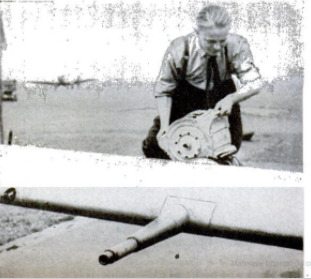

French Hispano-Suiza company brought

out a short-barreled 37-mm. gun mounted

in the notch of a V-type engine and firing

through a hollow propeller hub.

This gun was a single-shot type, and thus

completely lacking in true air fire power,

but its mount was exceedingly well thought

out, and variations of it are used today in

cannon-firing planes.

The Germans, meanwhile, had worked on

a Becker 20-mm. gun with a 12-shot

magazine. It never was very success-

ful, and after the war the owner sold

out his patents to the Swiss Oerlikon

firm. What happened later is an inter-

esting example of how military designs

circulate. Oerlikon continued to de-

velop the design, and later sold patent

rights to Hispano-Suiza. The French

firm, in turn, passed its designs on to

the British. Later the United States

took it over, modified and improved the

design, and is now using a so-called

Hispano 20-mm. in some versions of

the P-38 Lightning and P-39 Airacobra

fighter planes. The Germans also have

a short-barreled Oerlikon FF model,

but are known to be replacing it with

a high-velocity Mauser 20-mm. gun.

Our own ordnance experts carried on

numerous experiments during World

War I, one of them involving the Davis

“no-recoll” gun, an unconventional

weapon of about 2%-inch bore. It was

recognized that the element of recoil

was one of the biggest limitations to

the firing of powerful guns from air-

craft. The Davis gun tried to solve

this by discharging a dummy slug or

a load of shot backwards from its

elongated breech at the instant the ac-

tual projectile was fired from the muz-

zle, so that the counteracting forces

balanced each other and eliminated re-

coil at the gun's mount.

Army ordnance even considered using

a five-inch gun of this type, but after

thorough tests the Davis gun was dis-

carded, mainly because it could not be

aimed quickly and because the breech

discharge was found to be just about

as dangerous to near-by friendly air-

craft as its projectile was to the enemy.

Later a light 75-mm. mountain howitz-

er was prepared for plane mounting, but

was never test-fired.

America’s greatest progress, how-

ever, was made in the development of

specialized aircraft machine guns, and

the pioneer work was carried out by

our “gun wizard,” the late J. M. Brown-

ing, probably the world's greatest de-

signer of automatic weapons.

Browning, the designer of the entire

family of machine guns used by the

U. 8." armed forces, first concentrated

on a 30 caliber aircraft machine gun,

and produced a 22-pound, air-cooled

weapon with a rate of fire of 1,200

shots a minute. It snaps out 150-grain

bullets (about 47 to the pound) with a

muzzle velocity of 2,750 feet a second.

The same Browning design in a .303

caliber ver-

sion is now the standard British aircraft

machine gun.

But U.S. airmen now favor the larger

Browning 50 caliber air-cooled gun, and

say flatly that it is the finest large-caliber

aircraft machine gun in the world, Weigh-

ing less than three times as much as its

little brother, it throws four times as much

lead per second, and throws it with a heav-

fer punch. The muzzle velocity of its 800-

grain (nine to the pound) bullets is 2,900

feet a second, and after they have traveled

1,800 feet in less than three quarters of a

second they still have a striking velocity

of 1,950 feet compared with the .30 cali-

ber's 1,500 feet. The .50's rate of fire ranges

from 700 to 850 shots a minute, depending

on whether it is firing free or is slowed

down by synchronization with the propeller.

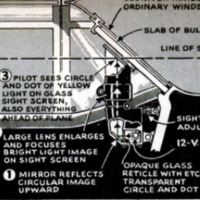

A synchronized Browning is fired by a

mechanical trigger motor attached to its

receiver and connected through a solenoid

and semiflexible tube with an impulse gen-

erator which is part of the airplane engine.

This is really a form of high-speed semi-

automatic fire, since the trigger motor ac-

tuates the trigger for each shot. This de-

vice, produced by Army Air Force engi-

neers, is a vast improvement over the often

unreliable hydraulic, rocker, and flexible-

shaft synchronizers used in 1918.

Nevertheless, modern practice tends in-

creasingly toward the use of wing guns to

avoid any synchronizer and to take advan-

tage of the gun's full rate of fire. The wing-

mounted gun is fired by a remote-controlled

solenoid, and continues to fire as long as the

trigger is depressed and the ammunition

holds out. Occasional trouble with belt-fed

ammunition has been eliminated by the

U.S. development of a disintegrating me-

tallic-link belt. Each cartridge, acting as a

pin, joins two metal links. When an empty

cartridge case is extracted and ejected, the

empty links that held it to the rest of the

belt fall apart and tumble out with it.

The development of more efficient armor

naturally stimulated the demand for harder-

hitting guns. The United States was well

abreast of the trend and by the time the

present war started had an excellent 37-

mm. cannon ready for production. This gun,

with a bore of about 11; inches, is recoil-

operated and fires 1%-pound high-explosive

shells at a rate of 125 to 150 a minute. The

shells have supersensitive nose fuses which

will burst the charge on contact with the

lightest airplane fabric. Armor-piercing

shells of about two pounds also are fired.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Arthur Grahame (Article Writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1943-09

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

82-87, 212

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public Domain (Google Books)

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Matteo Ridolfi

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Popular Science Monthly, v. 143, n. 3, 1943

Popular Science Monthly, v. 143, n. 3, 1943