-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

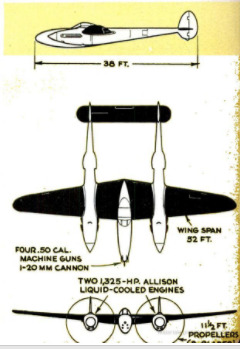

The new P-38 "Lockheed Lightning"

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Title: German pilots renamed it "Gabelschwanz Teufel" (fork-tailed devil)

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

THE U.S. Army prosaically called its

new fighter-interceptor “P-38." Lock-

heed Aircraft engineers and test pilots

called it “Lightning,” and that name

stuck with the combat pilots who flew it.

And now the Germans have a word of

their own for this twin-engine, twin-

boom aerial destroyer. Nazi pilots shot

down and captured in recent operations

bitterly referred to it as that “Gabel-

schwanz-teufel!”—fork-tailed devil!

But under any name at all, it's a lot of

combat airplane—one of the fastest,

highest-flying, hardest-hitting ships ever

turned out. For all-around versatility

and power the P-38 is in a class by

itself. It has been used successfully as

a fighter, interceptor, bomber escort,

bomb carrier, low-level strafer and tank-

buster, long-distance reconnaissance ship,

and high-altitude photographic plane.

Performance on most of the major bat-

tle fronts has shown the Lightning to be

equally effective flying from hastily

carved-out jungle fields in the far Pacific,

from cramped and rocky fields in the

Aleutian Islands, from the sandy wastes

of North Africa, and from the mist-bound

runways of England. One of its most im-

portant services was to make possible

American daylight bombing raids over

Germany. The Lightnings provided fight-

er escort at high altitude hundreds of

miles from the home bases, fending off

enemy attacks over the target area for as

much as an hour, then accompanying the

bombers on the dangerous return

flight and seeing them in to a safe

landing.

P-38's didn't swing into action as

soon as the United States was plunged

into the war. Our enemies unques-

tionably knew that we had a ship of

this unconventional design in the

works, but they couldn't know much

about its performance and fighting

characteristics. Wise military strate-

gy in a case like that dictates that

the new weapon be withheld from

action until it can be assembled at

the proper places in quantities large

enough to take maximum advantage

of its surprise punch.

Squadrons of Lightnings were

organized first in the Pacific area,

then others were sent to England,

and finally the plane emerged in

North Africa as our main fighter

type for that theater. The ship has

been a thumping success in all three

theaters of war.

Probably the first official combat

involving P-38's was in the Aleutians,

when the fork-tailed ships suddenly

popped out of a cloud and shot down

two Japanese K-97 four-engined fly-

ing boats and two escort fighters.

Even more significant than the vic-

tory itself was the fact that this

combat dispelled a notion that the

Lightning was a high-altitude ship,

unable to perform at lower levels.

There isn’t any high altitude to speak

of in the fog-shrouded Aleutians.

Even more spectacular in result

was the Lightnings’ first battle with

the Japanese in New Guinea. Twelve,

of the P-38’s ran into a much larger

enemy group, including some seven

“Val” dive bombers and an escort of

25 or 30 fighter planes—‘Zekes,”

‘““Haps,” and “Oscars.” (Zeke and Hap are

the two current versions of the well-publi-

cized Jap Zero fighter; Oscar is another

fighter plane, the Nakajima 97.) The Light-

ning pilots shot down 15 enemy craft and

damaged several others which probably

didn’t get back to their bases. None of our

pilots were injured and only one of the

planes was damaged.

The P-38 had another brilliant debut in

North Africa, one squadron destroying 15

enemy planes in the first day's operations

over the Gabés-Sfax area of Tunisia. Later

the planes went on important ground-straf-

ing missions and knocked out 11 tanks in

two days, along with much enemy transport,

including trucks, armored cars, and motor-

cycles.

The Lightning has fought it out there on

even terms with the very hottest enemy fight-

er planes, among them the German Messer-

schmitt 109, 110, and 210, and the Focke-

‘Wulf 190. American

pilots swear by their

ship, and vow it is

the best pursuit job

in action there.

This actual battle

experience has

served to dispel some

of the doubts airmen

and Army men felt

about the P-38 de-

sign when it first

became known. To

sum these doubts up:

Wasn't it too big—

“just too much air-

plane for one man?”

Wouldn't it lack fight-

er-plane maneuver-

ability? Would that

open-work twin-boom

construction have the

strength to stand up

and take the punish-

ment of military oper-

ations? And wouldn't

that same construc-

tion make it impossi-

ble for a pilot to get

out safely in a para-

chute if the occasion

arose?

The answers have

come along fast under

war conditions. The

P-38 is beyond any

doubt a first-class one-

man fighter ship. As

for its maneuverabili-

ty, some of the Amer-

ican pilots in North

Africa were so en-

thusiastic they told correspondents they

could turn inside a Spitfire. Their testi-

mony naturally must be taken with at least

a grain or two of salt; other factors being

approximately equal, the smaller and lighter

airplane always should have greater ma-

neuverability than the larger and heavier

one. And the huskiness, power, and long

range built into the Lightning must have

required some slight sacrifice of other

characteristics, Nevertheless, the battle

performance of this P-38 against Germany's

best ships is proof that it has maneuver-

ability enough to play in the big league of

air warfare.

The question of parachuting from the

ship was tricky, but it has turned out that

the trick can be done. A pilot can bail out

either by flipping the ship over on its back

and dropping from the open hatch, or by

putting it into a stall and stepping back

and down nto the space back of the cockpit

and between the twin booms. This may

sound complicated, but it is not a simple op-

eration to bail out of any hot ship, and the

baller always must follow a prescribed tech-

nique to avoid the fast-moving tail and

elevator surfaces.

There remained the question of the ship's

strength, and a big part of that was whether

the twin-motor arrangement wasn't a real

weakness—just two things to get hit or go

wrong. The growing list of Lightnings that

have come in all right on one engine has

set that point at rest; in fact, the climbing

powers of the ship with an engine out of

action have been a delightful surprise to

more than one hard-pressed pilot.

As for the structural strength of the plane,

startling proofs of that came in recently

from battle areas half the world apart. Over

New Guinea Lieut, Kenneth C. Sparks, of

Blackwell, Okla, got into a tight dogfight

with a Zero, and here is what he reported:

“Our right wing-tips hit, spinning the

Zero around so that its propeller struck the

trailing edge of my wing. He went down

smoking and I kept on going.”

Lieutenant Sparks admitted it was a

tough jolt, but he was unhurt and his plane

showed no damage except for a slight

chewing up of that wing.

Around the same time, a group of Light-

nings went out on a strafe in Tunisia, and

pressed their attack home on one enemy air-

field at such a low altitude that one of the

ships knocked over a telephone pole. Capt.

Mark Morne, of Hinsdale, IIL, in charge of

the operation, reported laconically:

“Fortunately the accident only dented a

wing of the piane, and he returned safely.”

Airplane designers don't advise using their

ships for disrupting enemy communications

in quite such a direct manner, but it doesn't

hurt pilot morale to know that you can get

away with it if the occasion should arise.

Nothing very much like the P-38 had been

tried out up until 1937, when the Army

called in the nation's plane makers to

study specifications for a new fighter aimed

primarily to intercept any air raiders that

might approach our coasts. Speed, range,

and fire power were the prime requisites.

The Lockheed company didn't have much

military background, but Hall Hibbard,

chief engineer, and C. L. Johnson, chief of

design, thought they might have the answer

in their private notebooks.

From the beginning they planned on a

twin-boom, twin-engine ship. Twin engines

would give added power and added safety,

in case one power plant failed, plus better

vision for the pilot and a chance to incor-

porate heavy gunpower in the nose without

getting into the technical problem of syn-

chronizing the guns to fire through a

propeller arc.

Twin booms promised excellent control

plus improved streamlining—a notion which

worked out so well, by the way, that the

present model, with its tricycle landing gear

retracted, presents no greater drag than a

card table 27 inches square.

The first ship began its flight-testing on

December 30, 1939, and a few days later

made a hop from California to New York

in which it loafed along at never better than

two-thirds throttle, made two stops for fuel,

and completed the run in seven hours, 45

minutes.

Minor changes in design were effected,

and improvements suggested by actual use

incorporated. It was not until September

1940 that the first actual production model

rolled off the line. Some airmen, pointing

out that the ship was heavier than a 10-

passenger commercial transport plane, still

thought it was a freak, with no real future

as a fighter. The Army knew better, but

took the wise decision to keep its husky

baby under wraps until it had enough of

them to deliver a solid punch.

The combination of power, clean aero-

dynamic design, and a quick-acting combat

flap enables the P-38 to fly great distances

and then battle on even terms with enemy

interceptors hundreds of miles from its own

base. The ship can take off and land at 80

miles per hour, fly faster than 400 m.ph.,

climb to 40,000 feet, carry up to two tons

of bombs for short distances, and outrun the

speediest enemy if that becomes necessary.

That combat flap, developed when the

Army called for increased maneuverability,

increases the wings’ lift substantially while

increasing the drag only slightly. Thus the

P-38 can roar to its objective at top speed,

and in three seconds the pilot can lower the

flaps to transform his ship into an acrobatic

dogfighter, dive bomber, ground strafer, or

precision bomber. After raising the flaps—

time, four seconds—he can streak for home,

then lower them again to land safely in

snow, soft earth, or a rough field.

Although a heavy fighter, the Lightning

apparently can be maneuvered in a fairly

short radius, and has shown a surprising

ability to climb on one engine even in

combat with the vaunted lightweight Zero.

Its propellers, driven by 1,325-hp. Allison

engines, rotate in opposite directions, nullify

ing the torque and giving it equal maneuver-

ability to either side. Pilots have taken

advantage of that to blast many a Jap or

Nazi flyer who could pull out of a dive only

to the right because of torque. |

Its high speed and altitude have made

the Lightning invaluable upon occasion as

a photographic reconnaissance ship. Stripped |

of armament, it can snap and run away in

broad daylight. Painted dead black for night

work, it can get into position for the run, |

pop flares, snap its pictures, and glide off |

like a dark cloud before the wind. |

In thie connection, it is an odd fact that

the Lightning's first shooting encounter with

the enemy occurred while the ship was un-

armed. Capt. Karl Polifka was taking |

pictures over Lae and Rabaul, New Guinea,

when a flight of Zeros jumped him and

knocked out his port engine in the first

burst. Unable to fight back, Capt. Polifka

climbed to 25,000 feet on the remaining

engine, evaded the foe, and got home with

photos which were officially credited with

helping to win the Battle of the Coral Sea.

As fighters go, the P-38 is a big ship and

a strong one. It can take a lot of gunfire

punishment without crumpling, for its wings

are double-skinned and its strength mem-

bers double-stressed. If a wing is riddled,

the spars can support the ship's weight; if a

spar is severed, the skin itself has structural

strength to hold together for the homeward

flight.

No other fighter surpasses the P-38 in

sustained fire power. It has various combi-

nations of armament, a typical arrange-

ment being four .50 caliber machine guns®

and a 20-millimeter automatic cannon, all

concentrated in the nose, whence they can

deliver an intense slash of steel and ex-

plosive. The pilot also can do a lot of

shooting without a reload; the Lightning

normally carries some five times the weight

of guns and ammunition packed by lighter

ships such as the Zero.

Most recent additions to the Lightning's

equipment are combinations of extra gas

tanks, smoke tanks, and bombs. The stream-

lined, droppable fuel tank of 150-gallon

capacity enables the ship to protect bombers

over a combat range of 750 miles and farth-

er. Over shorter ranges, P-38's have carried

as much as two tons of extra equipment,

including medium-size bombs.

Extra range also has made the P-38 a

handy ship for delivery to the war zones.

Lightnings flown to the Aleutians gave the

Japs a rude surprise early in the war. Hun-

dreds of them have made mass flights across

the North and South Atlantic. For such

hops, each plane carries two extra 165-

gallon fuel tanks, one under each wing. When

the gasoline is used, the tanks are jettisoned.

Since P-38 pilots have no time or equipment

for navigation, a Flying Fortress accom-

panies each flight as “shepherd.”

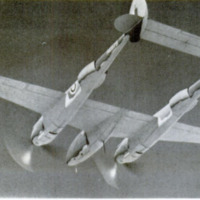

The P-38 is getting around in this war,

and you may see it anywhere. If so, it will

be an easy ship to spot from the ground—

partly because of the forked tail that im-

pressed the Germans so forcefully, and

partly because of the front arrangement of

wing, nose, and two engines, which gave it

the airmen’s poetic description of “three

bullets on the edge of a sword.”

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Andrew R. Boone (Article Writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1943-09

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

96-100, 206, 208

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public Domain (Google Digitized)

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Matteo Ridolfi

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Popular Science Monthly, v. 143, n. 3, 1943

Popular Science Monthly, v. 143, n. 3, 1943