-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

U.S. fighter planes overview and comparison

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Title: How America is using her Ships Fighter

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

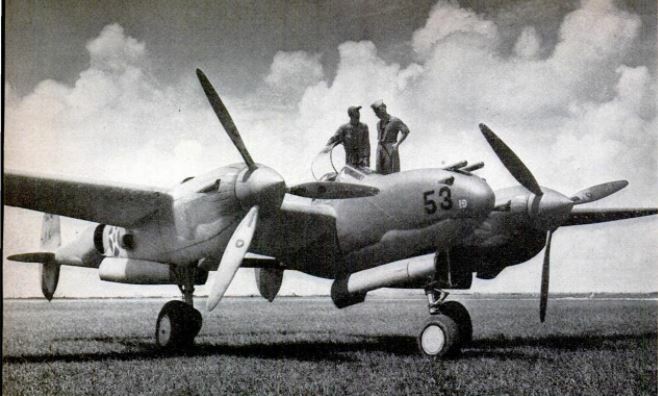

WHERE is a U. S. Army

fighter plane—the Lock-

heed P-38—which, viewed

from a certain angle, looks

like three airplanes instead

of one, until you see that it

consists of a fuselage mount-

ed between two slim engine

nacelles and two sets of tail

surfaces. Here is another-

the Republic P-47B—packing

about the same weight and

wallop as the P-38, but utter-

ly different in size and con-

tour, with a single engine 80

large that it dwarfs the rest

of the plane. And still others,

some of more or less “con-

ventional” design like the

Curtiss P-40's, with the pilot

sitting amidships behind the

engine, or the engine in back

of the pilot as in the Bell

P-30C, or with pusher pro-

pellers like the Bell YFM.

They differ in what can be

seen and more in what can-

not be seen—in armor, fuel

tanks, superchargers, and

auxiliary equipment —and yet

every one of them is a U. S.

Army fighter and nothing

else.

Why should planes In the

sume general category, flown

by the same service, show

such variations in design? One reason is

that development is proceeding at a very

rapid pace, and a lot of good ideas are com-

peting for supremacy. But a more com-

pelling reason is the complexity of the

problems which call for solution. After all,

to say that a plane is designed to fight is

pretty vague. When—by day or by night?

Where—at 30,000 feet altitude or 3,0007

Whom—is it to attack enemy bombers or

protect friendly bombers? When such

questions are asked it becomes evident that

the fighter plane must be designed for one

or two fairly specialized jobs.

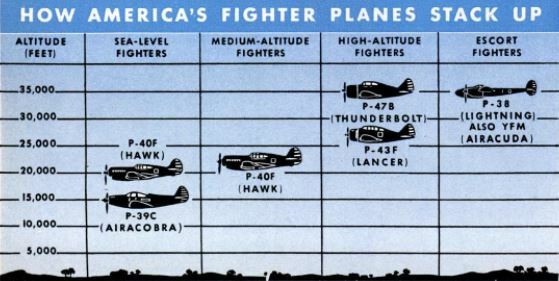

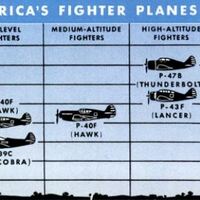

When we survey existing models of fight

ers on this basis, a more or less logical

pattern of design and development begins

to emerge. There are three principal types

of fighters on the basis of range. The inter-

ceptor is designed for operations close to its

base. The pursuit plane for night fighting

and extended day operations requires a

considerably longer range, while heavy

fighters for escort duty with bombers cover

still greater distances.

First, the interceptor. The name indicates

what its job is—to get off the ground on the

shortest possible notice, climb with the

greatest possible speed, and scare off or

shoot down bombers, if possible before they

can reach their objective. It is essentially

a flying machine-gun nest—a small, highly

maneuverable plane with a big engine. The

engine must be big to get the plane up

there fast and to give it the advantage

over the bomber in speed—which, nowa-

days, calls for 400 m.p.h. and up.

The interceptor is an inherently limited

type of plane, capable of carrying only a

few guns, no great amount of ammunition,

only enough gas for a few hundred miles

of flight, and one man to do all the work of

piloting ‘and shooting. For the interceptor

pilot the motto is, If at first you don’t suc-

ceed, give up and fly home. He just hasn't

the ammunition or the fuel to do anything

else. And there is no point in sending him

up unless the general locality where he will

‘meet the bomber is pretty definitely known.

For all these reasons the interceptor is es-

sentially a daylight weapon.

But because the interceptor can do deadly

work when the conditions are right, bomb-

ers fly mainly at night. The night pursuit

plane does not need the high maneuvera-

bility and top speed of the day interceptor.

It is not going to engage in a dogfight. On

the other hand, it needs much more gas

capacity, for ordinarily it will take some

time to find the bomber. For this purpose

the night fighter is equipped with some

form of long-range detection device. Even

after the bomber is located and sighted,

considerable stalking time must remain in

the gasoline tanks. When the opportunity

for the kill finally presents itself, the pur-

suit plane must close in and do the job

quickly.

Day interceptors are almost

always single-engine planes.

For a given amount of power

a single-engine plane is more

maneuverable than a two-

engine plane. Night fighters

may have one engine or two.

The multi-engine fighter may

also be advantageously used

in extended day pursuit opera-

tions. It carries considerable

armament in the form of

20-mm. cannon or larger, and

machine guns of .30 and .50

caliber. The crew normally

consists of two men. Such

planes are suitable for patrol

work and long-range hunting,

and also for escorting friendly

bombers.

The design of fighter planes

is conditioned as much by

bomber performance as by

the characteristics of other

fighters. It is the bomber which works

destruction on land and sea, and the ulti-

mate function of the fighter is to down

bombers. The fighter tackles an enemy

fighter to put him out of the way so that

he or someone else can get a whack :t a

hostile bomber or some similar flying ob-

jective.

The way in which bomber design affects

fighter design is: well illustrated by the ap-

plication of superchargers, first to bombers,

then to pursuit planes. A gasoline engine

normally loses power as it gets into the

rarefied atmosphere of the higher altitudes,

where the cylinders gulp in less air for each

piston stroke. This loss can be counter-

acted by increasing the size of the cylinders

—to which there is a limit—or by super-

charging. The original Boeing Flying Fort-

ress had a top speed of 250 m.p.h. at 13,000

feet with its four motors wide open. With

the same motors supercharged, it is good

for more than 300 m.p.h. at 20,000 feet, and

it can cruise comfortably at 245 m.p.h. at

30,000 feet. The same thing must be done

for fighters intended to operate at high alti-

tudes, but it is harder because of limited

space and weight allowances.

With the above considerations in mind we

can discern the general design pattern of

our current Army fighter models. Almost

all the types to be described have proved

their merits in actual combat. Naturally

some are better than others. A few will fall

by the wayside, others will undergo further

development. Later models will be quite

different from their prototypes, and a lot

better.

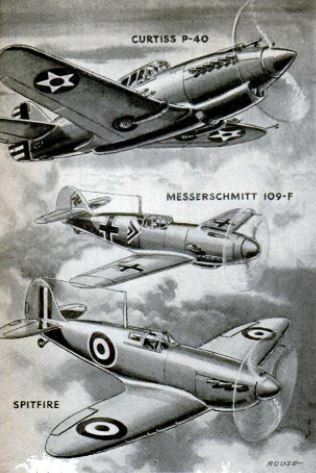

Typical of the one-engine, one-seat fight-

ers designed for sea-level operation—which

means between sea level and an altitude of

about 20,000 feet—are planes like the Bell

P-39 Airacobra and the Curtiss Hawk line.

The P-39C is powered by a 12-cylinder,

1,150-h.p., liquid-cooled Allison motor which

drives a three-bladed tractor propeller

through a 10-foot extension shaft. Landing

gear is of the tricycle type. The armament

consists of a 20-mm. cannon in the pro-

peller hub, as well as light and heavy-caliber

machine guns. The weight of the plane,

loaded, is 7,380 pounds, this includes suffi-

cient ammunition for fairly sustained fire.

The range at the most economical cruising

speed is 1,100 miles, which is very good. A

plane with these characteristics is more

than a match for the equivalent Messer-

schmitt, the Me-109F, and approximately

equal to the British Spitfire. But only up

to about 16,000 feet.

The later Curtiss Hawks are designed for

somewhat higher ceilings. The current mod-

el stems from the original P-36, through the

P-37 and the more highly streamlined P-40D

and E. The earlier P-40’s compared favor-

ably with the older Spitfires and Hurricanes;

the latest type is believed to equal or excel

any of the European fighters. Increases in

speed and high-altitude performance have

been achieved in spite of greatly increased

armament, ammunition loads, and armor

plate.

U. S. Army fighters specifically designed

for high-altitude operations —between say

16,000 feet and the present effective ceiling

of about 35,000 feet—include the Republic

P-43F Lancer and the same company’s

P-47B Thunderbolt. The P-43F is powered

with a Pratt & Whitney Twin Wasp 1,200-

h.p. air-cooled engine. The loaded weight

is slightly less than that of the Airacobra—

6,900 pounds. Armament consists of large

and small-caliber machine guns. The com-

panion Republic pursuit plane, the P-47B, is

at present the most powerful of American

single-engine, single-seater fighters. The

motor is a 14-cylinder, 2,000-np. Pratt &

Whitney radial, driving a four-blade pro-

peller. High-altitude performance is ob-

tained by means of a turbo-supercharger.

This plane is said to have reached a speed

of 680 m.p.h. in a power dive.

The U. S. Army has two twin-engine

fighters for escort service and special mis-

sions. One is the Lockheed P-38 Lightning

and the other the Bell YFM-1A Airacuda.

Both are armed with cannon and machine

guns. The P-38 is the faster of the two,

while the YFM has much the greater range

—some estimates run as high as 3,000 miles.

The P-38 carries a crew of one or two, the

YFM a crew of five. For high-altitude serv-

ice these heavy fighters are equipped with

turbo-superchargers. Weights of two-en-

gine fighters run around 11,000-14,000

pounds, as compared with 6,000-8,000

pounds for single-engine fighters.

The U. S. Navy uses air-cooled engines

for its carrier-based fighters. Such planes

must be equipped with arresting hooks

which engage horizontal cables on the car-

rier deck to bring the plane to a quick stop

in landing. This calls for stronger and

heavier undercarriages. The wings of some

of the later types fold so that more planes

may be accommodated in a given deck

space. Gasoline capacity is at least 50 per-

cent higher than in land-based planes of the

same type. In spite of these handicaps,

naval fighters are nearly as fast as the

equivalent Army aircraft and the service

ceilings are about the same.

Principal naval fighters are the Brewster

Buffalo (F2A) and Grumman Wildcat

(F4F). The latest model of the latter, the

F4F-3, is a single-place monoplane powered

with a 1,200-h.p. Pratt & Whitney air-cooled

twin-row engine. Its cruising range is about

1,000 miles. Most efficient operation is at

20,000 feet. Normal armament consists of

four 50 caliber machine guns. For light

dive-bombing operations two 11-pound

bombs may be carried. This plane is said

to have been dived at over 500 m.p.h., but

another Navy fighter, the Vought-Sikorsky

Corsair, F4U-1, is even faster. The Navy

also has an experimental two-engine fighter,

the Grumman Skyrocket (XF5F-1).

It is interesting to compare these Ameri-

can fighter planes with European models.

The German Messerschmitt Me-100F is in

the same class as our latest P-39's and

P-40's. It is powered with a 1,150 h.p.

Daimler-Benz DB-601N motor, liquid-cooled

and supercharged for

a 40,000-foot service

ceiling. The speed is

362 m.p.h. at 13,000

feet, and 380 m.p.h.

at 21,000 feet, the

latter being the top

speed. Range is 370

miles at 307 mph.

(1.2 hours), and 600

miles at 262 mph.

(2.3 hours). The

principal novelty of

this fighter is a Mau-

ser 15 or 20-mm.

cannon firing 900

rounds per minute—

just below the nor-

mal rate of fire of a

modern machine gun.

Loaded, the plane

weighs 6,000 pounds.

It is said to have

been especially de-

signed for dogfights

and admittedly has

a faster climb than

the British Spitfire, but the latter has shown

better maneuverability in encounters.

The British Beaufighter I is a two-engine,

two-place fighter adapted from a medium

bomber. Each engine is rated at 1,400 h.p.

The armament is very heavy—four fixed

cannon in the fuselage and six fixed ma-

chine guns in the wings. The maximum

speed is fair—330 m.p.h., and the service

ceiling is 20,000 feet. The opposing Ger-

man fighter, the twin-engine Me-110, has a

higher top speed—365 m.p.h. Another Ger-

man twin-engine fighter, the Focke-Wulf

FW187, with about the same maximum

speed (at 20,000 feet) is said to have a

service ceiling of 39,000 feet. Equivalent

American two-engine fighters like the Lock-

heed P-38 are believed to be superior in

speed, climb, and hitting power.

The designer of a modern fighter plane

strives for maximum speed, power and alti-

tude performance, maneuverability, fire

power, and armor protection. Speed, to pre-

vent the enemy fighter or bomber from es-

caping by diving or straight flight. Power,

to prevent the enemy from escaping by

zooming, and maneuverability so that he

cannot elude his pursuer by a sudden change

in direction. Fire power is vital so that

the enemy may be put out of commission

in the few seconds of close engagement.

Since the enemy has exactly the same pur-

pose, the best possible armor protection

must be provided.

Almost all the basic factors—speed, pow-

er, altitude performance, weight, etc. are

tending to rise. Speeds are or will soon be

between 400 and 450 m.p.h. at altitudes be-

tween 20,000 and 85,000 feet. This means

that the airplane must be as small as pos-

sible to reduce drag. Weights, nevertheless,

are increasing because of ordnance, armor-

protection, and engine requirements.

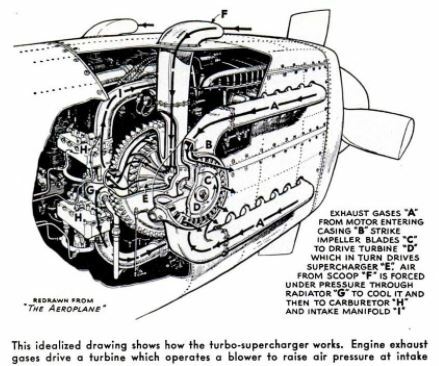

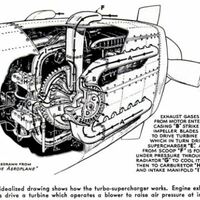

Supercharging is essential for efficient op-

eration at high altitudes. Two general types

of superchargers are at present available—

centrifugal blowers or compressors gear-

driven by the engine, and turbo-supercharg-

ers which utilize the exhaust gases to drive

a turbine wheel which in turn drives the

compressor. The geared superchargers are

simpler, but they work well only at the

middle altitudes.

The propeller presents a similar problem.

A propeller which may be satisfactory at

sea level and under take-off conditions will

have entirely unsatisfactory propulsive efi-

ciency at high altitudes and high speeds. A

propeller suitable for a medium-powered

engine will not work with a larger engine.

The propeller tip speed can be increased

only to a given point, and of course the

diameter is limited by structural considera-

tions. Consequently the tendency is toward

a greater number of blades.

Modern propellers for high-altitude flight

must be equipped with pitch control. Be-

tween take-off and terminal-velocity dive

the pitch range may have to be as high as

40 degrees. The pilot cannot attend to it;

he has too many other things to do. Auto-

matic pitch-control devices are mandatory.

Protection and fire power seesaw in the

air as in battleship design. Bigger guns

call for thicker armor, thicker armor calls

for bigger guns, but guns and ammunition

add weight and cut down speed. Again the

solution is by compromise—the continued

installation of both .30 and 50 caliber ma-

chine guns on fighters is one example. At

first 30 guns were adequate. Heavier ar-

moring brought .50 guns and cannon.

Small cannon are valuable when the pur-

suit plane tackles a bomber. Aerial en-

gagements with machine guns must be

fought at close quarters, usually not ex-

ceeding 300 meters. On the other hand, a

pursuit plane armed with a cannon can

damage a bomber and sometimes bring it

down, without coming within the effective

fire area of the bombers machine guns.

Radical developments in future fighter

designs are possible, even probable. Per-

haps the most rapid progress may be ex-

pected in night fighting and in what may

be called engineering the pilot for combat

at high altitudes. In wartime these and

other matters are best left to the imagina-

tion. The enemy will find out about them in

due course, but he will have to get the in-

formation in the air, and, we may hope, at

a high cost.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Carl Dreher (Article Writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1942-04

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

52-59

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public Domain (Google Digitized)

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Roberto Meneghetti

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Popular Science Monthly, v. 140, n. 4, 1942

Popular Science Monthly, v. 140, n. 4, 1942