-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

U.S. Army employ FM Radio

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Title: FM Radio Joins the Army

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

JUST in time for America's supreme war

effort comes a new system which jumps

many of the hurdles in radio communication

for military and emergency defense work.

It is called FM, in commercial broadcast-

ing already famous as a static eliminator.

A few years ago, communication with a

mechanized army in the field had to be ei-

ther two-way communication by the old

telegraphic code signals requiring trained

operators, or one-way communication by

voice. Radiotelephony broadcast to mobile

units such as command cars, trucks, recon-

naissance patrols, tanks, etc. required a

powerful transmitter to overcome noise and

interference. Such a transmitter was too

large, heavy, and cumbersome to be in-

stalled in a mobile unit to provide talking

back. For tanks which, in themselves, set

up violent disturbances, even one-way voice

communication was unreliable.

Today, the operator of a tank, speaking

in an ordinary tone, can talk quietly with

other tanks or with command cars. He can

receive orders from command posts or send

back news of his position or of the action in

which he is engaged. Only the voice is used.

The tank operator's voice is not communi-

cated through an ordinary microphone but

through two disks pressed against his

throat. He hears through headphones built

into his helmet. Thus his hands are left en-

tirely free. Tuning is done automatically by

the use of push buttons and requires no skill.

Ordinary communication from a tank is

short-range—about one mile. Power can,

however, be increased by the operator if

necessary either to increase the range or to

blank out another signal—a new FM tech-

hique which will be described

later.

A tank platoon has been put through rap-

id and complex operations entirely by radio

with no visual signals. This simple two-way

system has made possible a novel method of

reconnaissance called the Combat Zone

Warning Service, especially useful in anti-

tank maneuvers. CZWS has, in effect, mech-

anized the old scouts which used to move out

on all sides of an army unit to give warning

of the enemy's approach or other doings.

At headquarters is a 250-watt FM trans.

‘miter mounted on a truck. From it orders

are sent out through relay stations to small

reconnaissance units. These have receivers

to pick up messages, and transmitters by

which they can talk back. Reconnaissance

units are small vehicles such as “jeeps”

which may be concealed in woods, bushes,

or other cover. Any of them which detects

enemy activity can send a message to the

relay station which may either relay it back

to headquarters or directly warn a combat

unit.

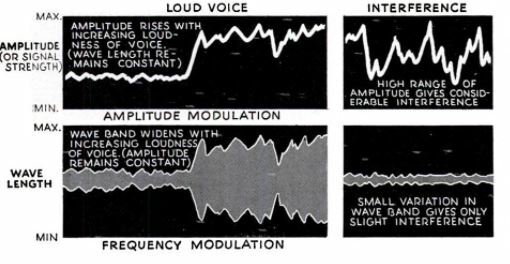

"All this has become possible through FM

—or rather through the particular frequen-

y-modulation system invented and perfect-

ed by Major Edwin H. Armstrong. As every-

one who has followed radio development.

knows, this system was invented primarily

to do away with static and man-made dis-

turbances which produce noise in the re.

ceiver. In the words of Major Armstrong,

this Is done by transmitting “a wave which

is different in character from the static”

and by using a “receiver which responds

only to this new type of wave and is deaf to

the ‘amplitude modulations’ of the noise

currents and substantially deaf also to the

small frequency swings occurring in the

noise by using a wide frequency band.” Ac-

tually, this “different” wave is a wave of

constant amplitude whose frequencv 1s

widely varied by the sound pattern im; >sed

upon It—an exact reversal of previous ac-

cepted practice. FM is further insured

against noise by operating in the ultra-high

frequencies. The informed general public

has come, in the last few years, to under-

stand this.

But what the public is only beginning to

learn is the immense advantage gained

from other incidental ef-

fects of FM which adapt it

s0 beautifully to military

and police use. Apart from

noise reduction, these are,

briefly: low-power opera-

tion, low-cost operation,

short-range transmission,

easy adjustment of range,

compactness of units, fa-

cility of operation by un-

skilled operators, complete

absence of distortion or

“squeal” caused by the in-

terference between signals.

and the opening up of a multitude of new

communication channels. Most of these ef-

fects are, of course, derived from the basic

properties of FM which make possible the

elimination of static and noise.

With the amplitude-modulation system,

called AM, the high power necessary to

overcome both noise and interference in-

creases operation cost and size of ap-

paratus. Furthermore, interfering signals

on the same frequency are difficult to drown

out.

FM does not drown out an interfering sig-

nal, it “blanks” it out. Only one signal can

come through at a time in an FM receiver.

The familiar jumble of sounds coming from

two stations using the same frequency—

which everyone has heard in his AM set—

is impossible with FM. The more powerful

signal always come through, clear and un-

distorted, even if its amplitude is only a

little greater. So the operator of an FM

transmitter can blank out other signals at

will by only slightly increasing his power.

Actually a ratio of 2 to 1 will blank out a

weaker signal on the same frequency

whereas a ratio of 20 to 1 is necessary in

AM to overcome such interference.

At the same time, this blanking out can-

not be done successfully at great distances,

for FM is essentially a short-range system.

Commercial broadcasting over distances

greater than 50 miles requires high antennas

on high ground. Therefore the enemy, even

if he possesses FM field equipment, cannot

blank out or “jam” signals unless he is very

near.

The Army learned of FM from the police.

About a year ago, a number of Signal Corps

officers and engineers from Fort Monmouth

were invited to Hartford, Conn, to see a

demonstration by the pioneer police users of

the Armstrong system—the Connecticut

State Police. The story of what they

saw will explain, better than any theo-

retical description, why the Army has

gone in for FM.

Connecticut, an area of 4,965 square

miles, is divided into ten barracks areas.

The barracks are not in the centers of

the areas they represent, and there are

no high antenna poles rising from them.

Yet in each barrack, a dispatcher sits

at a desk talking by radio with police

cars and with other barracks.

The dispatcher is handling the trans-

mitter by remote two-wire control, be-

cause a barrack and a transmitter re-

quire two different sets of conditions.

A barrack must be on a main highway,

easily accessible to motorists and handy

for sending out cars in a hurry. An

FM transmitter using ultra-high fre-

quencies should be on the highest

ground available and should be in the

center of the area to which it transmits.

So the 200-foot steel masts carrying the

antennas are put on hilltops, often in

the middle of woods or fields. In a

welded-steel shack below each mast is

housed the transmitter and receiving

equipment. From this shack—called

the “station” —wires run to the area's

barrack.

‘The dispatcher, sitting at his desk at

the barracks, is able to hear both the other

stations and the cars in his own area. He

may, if he wishes, ground the station-to-

station receiver by remote control so that

he will hear only a car which is calling him.

Police cars can also talk directly with other

cars.

Because of the factors of distance and

power, the local station is able to control

its local cars and blank out all other signals.

One of the Army visitors at the police

demonstration asked if the remote-control

wires were not vulnerable to saboteurs. The

answer to this question by Sydney E. War-

ner, Radio Supervisor of the Connecticut

State Police, reveals another advantage of

the FM system as it is laid out for police

work:

“That is a serious objection where an en-

tire system is dependent upon a single

transmitter. However, in this particular

system, there is ample overlap in the range

of each transmitter so that if, for any rea-

son, one fails, its traffic can be handled

through other barracks.”

Tests have shown that, in emergency,

even a car can be sent to high ground and

used us a dispatching point. “Thus,” says

Mr. Warner, “we also know that even if all

our ten fixed stations were put out of serv-

ice, strategic placing of cars around the

state would still enable the State Police

radio system to function.”

The Signal Corps men saw many tests, in-

cluding some in cities where ignition dis-

turbance was very high. They were able

to listen to both FM and AM receivers in

these traffic-congested areas. It was proved

conclusively that in nine or ten New York

City blocks (about half a mile) AM signals

were eliminated by noise, whereas FM sig-

nals were perfectly clear over a five-mile

distance.

tis easy to see why, after these demon- |

strations, the Army adapted the Armstrong

FM system to its needs. Quickly they vis-

ualized the small apparatus made for the

police, which could be stowed away in the

baggage compartment of a coupe, being

efficiently packed in a command car or a

small truck, or built into a tank. They im-

agined the quick automatic tuning being

handled, if necessary, by a “rookie.” Espe-

clally, they saw how signals could be kept

from the enemy by limiting the range. They

saw that signals could never be confused.

They saw, in short, speed, clarity, foolproof |

operation, and invulnerability.

Another wartime application of FM radio |

communication has come in the extremely

ticklish handling of freight in the railroad

yards of Government arsenals where the

cars carry immense loads of explosives and

where even a slight accident might have

terrific repercussions. To see how FM has

come to fit here, we should take a brief

look at the background of ordinary freight-

yard management.

Most Americans would be shocked to see

how old-fashioned and primitive this is. Not

even common block signaling Is used in

most railroad freight yards. Old visual sig-

nals such as the waving of flags and swing-

ing of lanterns are still in use when they

are not stopped by fog. A switching engi-

neer, after he has fulfilled one order, must

return to the dispatcher for the next. Ac-'

cidents in freight yards occur oftener than

railroad men like to tell. |

When the imzese new Government ar-

senals like Kingsbury and Elwood were

projected, the difficulties of a quick, efficient,

and safe handling of ordnance freight by

common methods was quickly foreseen. At

least, thought the traffic engineers, a block-

signal system should be installed. But as

this was investigated it turned out to be

not only extremely costly but its installation

would require much valuable time. So the

engineers turned to radio for a solution of

their problems.

Common AM communication had been

tried with long-run passenger traffic. When

ordinary steam locomotives were used it

worked weis enough. But it did not take

much imagination to see that any AM re-

ceiver installed in a Diesel-electric locomo-

tive such as were planned for the arsenal

yards would be stopped by noise. It was

then that the FM system came to the

notice of the men who were planning the

arsenal-yard communications. Today half

a dozen Government ordnance plants are

being equipped with it.

An example is the Elwood arsenal at

Joliet, Til, whose yard occupies 22 square

miles. There are 80 miles of track, 212

switches and 300 of the arsenal’s own

freight cars. Here nine locomotives will

handle trainloads of TNT, artillery shells,

aircraft bombs, and antitank mines 24

hours a day.

A 50-watt FM transmitter is controlled

(remotely) by the train dispatcher. A simi-

lar station is controlled by the yardmaster.

From these stations orders are sent out to

the locomotives. Each locomotive has a

transmitter (25 watts) by which he can

talk back to the stations, as well as a re-

ceiver.

With this Kind of communication, any

locomotive may be instantly located and

controlled. At Elwood there are also gaso-

line-operated maintenance cars and guard

cars. These may be summoned in case of

breakdown or sabotage, to any part of the

yard.

As the FM radio installation for large

freight yards costs less than one tenth of

the block-signal layout, it has been suggest-

ed that it should be adopted in commercial

yards throughout the country. Communi-

cations engineers to whom I have talked

estimate a 300 to 400-percent speed-up in

the handling of freight. With such an in-

crease in efficiency applied to transportation

of war material, the impending shortage of

freight cars due to steel restrictions could

easily be met.

It is always heartening to hear of “new

weapons.” FM has no direct destructive

power. But as a means of multiplying the

speed of armies and civilian defense, it is a

new aid to all weapons.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Roger Burlingame (Article Writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1942-04

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

82-86

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public Domain (Google Digitized)

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Roberto Meneghetti

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Popular Science Monthly, v. 140, n. 4, 1942

Popular Science Monthly, v. 140, n. 4, 1942