An airplane invented by Glenn Curtiss was used by the British Army during World War I

Item

-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

An airplane invented by Glenn Curtiss was used by the British Army during World War I

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Title: Real Flying Dutchmen

-

Subtitle: Mammoth air-boats that are at home in air and water

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

THE first man who

gave really seri-

ous thought to

flying across the Atlan-

tic—serious in the sense

that he actually built a flying-machine

to carry out his intentions —was Glenn

H. Curtiss. He decided that his

machine must have an enormous

radius of action, and to obtain it he

considered it necessary not only to

increase the size of the airplane, but

also to improve its efficiency.

The chief obstacle to an increase of

its efficiency was the landing gear.

The sheer weight and air resistance

of that appendage wasted fuel. But

when Curtiss considered the crew,

particularly their comfort and safety,

he went to the other extreme, and de-

cided to turn the landing gear into a

vessel as big as a sea-going launch.

The boat or launch proved to be so

heavy that before the machine could

get into the air it was found neces-

sary to leave behind most of the fuel.

Later he adopted the “sea-sled” type

of boat. While Curtiss was still ex-

perimenting the world war broke out.

He sold his experimental craft —the

America—to the British Government,

which used it very successfully in

patrolling the waters around the British

Isles.

Curtiss gave to the world a craft

that had some of the attributes of

both airplane and dirigible, alternately

flying and resting on the water.

Small flying-boats cannot live on

the ocean, and to become relatively

seaworthy, seaplanes must have

sealed catamaran floats, and the

men must be raised high above the

waves. Only a mammoth craft,

something with a huge hull, something

that will transform the flying-boat into

a flying galleon, can solve the problem.

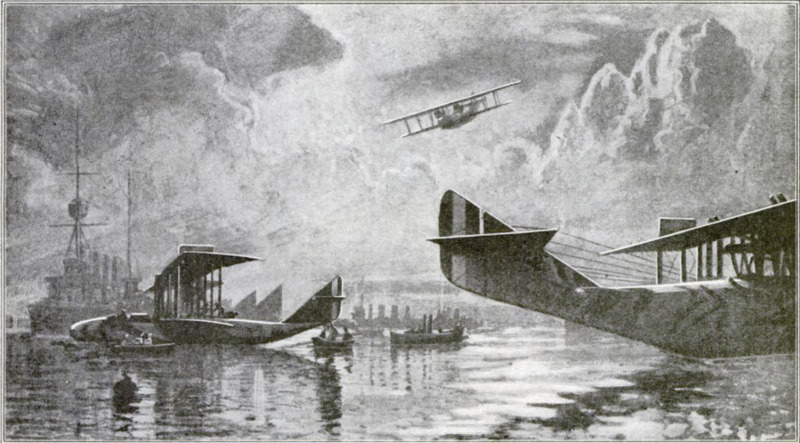

These huge flying galleons, as war

progress has finally shaped them, rival

in beauty the most picturesque old-

fashioned ships. With their wings

suggesting low-rigged ancient sails,

they resemble the pigmy vessels in

which the daring pioneer navigators of

the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries

crossed the Atlantic. Every structure

becomes beautiful when once it is per-

fectly adapted to its purpose. These

new flying-boats are beautiful for the

very feature that makes them prac-

tical —their raised tails. What is it

that an oarsman must know before he

can safely venture out upon a big body

of water? That he must cut the waves.

Our galleons of the air are dirigible

floating weather-cocks. From their

rounded compact hulls waves dash off

as harmlessly as from the caravels of

Columbus or from Hudson's Half-

Moon. They head into the wind as

quickly as a high-forecastled, high-

pooped ship of old, which was likewise

a floating weather-vane. Their high

tails, when they rest on the water,

head them into the teeth of the wind.

If the descent is too steep, the nose

may be tilted up, yet the high tail

drop clear of the water without splash-

ing and without breakage. Alighting

is a more delicate operation in a sea-

plane than in a landplane. It is only

too easy to come down nose first. Let

the pilot beware lest the prow be

caught in the water and the machine

turn a somersault.

It certainly seems a most interest-

ing coincidence that ships that in

truth navigate alternately the sea and

sky have now assumed the identical

and fascinating appearance of the

legendary Flying Dutchman.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Carl Dienstbach (Article writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1919-01

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

61

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Davide Donà

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Popular Science Monthly, v. 94, n. 1, 1919

Popular Science Monthly, v. 94, n. 1, 1919