Apparatus for sending wireless messages from airplanes

Item

-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

Apparatus for sending wireless messages from airplanes

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Apparatus for Sending Wireless Messages from Airplanes

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

PICTURE yourself speeding aloft

in a wireless-equipped airplane

with two officers of the Signal

Corps to obtain information that will

silence an enemy battery. The day is

clear, but it is difficult to locate the

guns because of the camouflage. Sud-

denly a bomb exposes a suspicious bit

of landscape.

“There they are!” cries the observer.

The others look in the direction in

which he points. Far below they see

what he has discovered—the well

masked muzzles of the guns that have

caused so much destruction. Even the

soldiers manning them are momentari-

ly in sight.

The observer quickly turns to his

wireless set and signals headquarters,

telling just in what direction he has

calculated the gunners’ fire should be

directed. Almost within the instant

the hand of the operator leaves the

transmitting key a veritable hail of

shells begins to fall about the battery.

They just fail to reach their mark,

however, so the observer sends another

message to headquarters—new direc-

tions for aiming. Then the fire is

swung slightly to the left and directed

squarely on the objective. The wire-

less has accomplished its mission, and

the airplane descends to the earth.

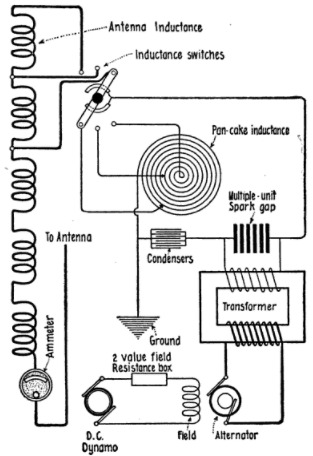

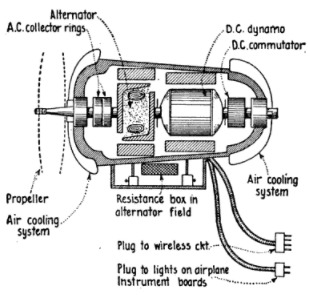

An inspection of the radio apparatus

in the airplane shows that it is some-

what light. Mounted on the forward

part of the flying machine is a tapering

metal case, hardly eleven inches long

and about six inches in diameter, yet

this contains an alternating-current

generator of two-thirds horsepower

and a direct-current dynamo to excite

the alternator. When the airplane

is in operation the propeller is driven

around 4,600 times a minute. The

dynamos on the same shalt whirl

around with it, and are thus made to

50 around ten times un fast na tho

Wheels of an automobile traveling at

forty miles an hour.

The alternator does away with un

interrupter on a spark coll. The

rapidly roveniag current s led directly

into the transformer primary. The

current emerging from the secondary |

winding, now stepped up to u very |

high voltage, finds itself first charging

the plates of the spark gap and then

overwhelming the air resistance and |

breaking through in the form of an

cletric spark. The condenser in the

circuit. shunting tho gap has in the

meantime rocoivod a chargo alo, and

the upark has helped to close the cir-

cuit containing the pancake induc-

tance, the gap and the condenser.

Following the rest of the cireui, it is

observed that the pancake is tapped

directly onto the antenna and ground.

The antenna consists of a reel of wire

buck of the observer's seat. This is

unwound as the airplane takes the

air and the antenna is lowered about

135 feat. A metal bobbin on the end

of it keeps this wire from fluttering

as it is swept almost horizontally in a

long graceful curve by the wind. The

“ground,” on the other hand, is merely

the wire stays between the planes

and inside of the canvas covering of

the wings.

The controls by which the operator

tunes hia set are on top of the instru

ment caso mounted at the front of his

compartment. With the first control

ho is able to change the power from

the alternator from low to high us he

gots farther and farther away from

his lines. When the switch is thrown

to high, the sparkegap length is in-

creased automatically, so tht he may

be sure that the spark will work as

efficiently as before. Throwing the

next control simply adds or subtracts

some of the pancake’s inductance so

that any of the three wavelengths of

150, 200 or 250 meters may be quickly

obtained. By this means, should the

airman wish to report a maneuver he

has discovered to a station, other than

his own, he changes to the different

wavelengths of that station, Every

time he does this he varies the induc-

tance in the antenna circuit slightly

until the ammeter in the same circuit

shows that the greatest amount of

power is being radiated.

‘This, then, is what you would have

to be familiar with if you were an

officer of the Signal Corps detailed to

airplane observation work. But then,

you may say, you have not been told

how the receiving is accomplished.

The answer to this is that it is not the

usual practice. It can be done, but

the added incumbrance to the aviator

and the necessity for increasing the

‘complexity of the system to overcome

the noise from the engine and the

rush of the air are advanced as argu-

ments against it. The observer is

given bh orders before ascending.

These he must fulfill to the letter;

furthermore, he is expected to use

initiative in the “tight places"—

when, for instance, he is menaced by

anti-aircraft guns or enemy wireless

men “Jam his messages.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Lloyd Kuh (Article writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1919-01

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

96

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Davide Donà

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Popular Science Monthly, v. 94, n. 1, 1919

Popular Science Monthly, v. 94, n. 1, 1919