-

Titolo

-

How U. S. Coast Guard removes floating derelicts in the Atlantic Ocean

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Title: The Derelict-Rival of the U-Boat

-

How the Coast Guard fights the grimmest menace of the sea

-

extracted text

-

PEACE hath its perils no less than

Price paraphrase famous

saying; and, while the menace

of the submarine has been re-

moved by the victory of the

Allies, the Coast Guard

must continue its never-

ending warfare against the

derelict.

“Another chapter has

been added to the mysteries

of the saw often have

you not read that in a news-

paper account of a ship that

never returned? Such are the

vicissitudes of storms and tidal waves,

so-called, that the reason for many dis-

appearances can never be known. But

the men who sail the Seven Seas be-

lieve that derelicts, the grimmest

menace of the sea in peace times, are

responsible for many marine disasters.

Such is the danger of the derelict

that it became one of the leading sub-

jects of discussion at an international

conference of the maritime powers held

at Washington in

1890. The confer-

ence recognized the

importance of a

systematic removal

of derelicts from the

paths of commerce,

and adopted resolu-

tions that something

should be done. But

after a few spas-

modic efforts the

Government again

lapsed into indiffer-

ence.

By 1906 the mari-

time interests of the

leading Atlantic sea-

ports appealed forei-

bly to Congress. An

act was passed au-

thorizing the construction of a special

derelict destroyer, and the responsibility

for systematically destroying derelicts

was placed upon the Revenue Cutter

Service, now the Coast Guard. The ves-

sel was completed in 1907, and the larger

revenue cutters were outfitted with

submarine mines and other appa-

ratus. Forthelasttenyearsthe

work of destroying derelicts

hasbeen vigorously carried on.

In general, there are but

two types of derelicts:

sunkenand floating. Sunk-

en derelicts, with their

spars projecting above

water, are generally found

in the routes of coastwise

traffic. Floating derelicts

drift promiscuously about at

the impulse of current and wind,

but sooner or later find their devious

way into the steamship lanes.

How many people realize that the

waters along the greater part of our

Atlantic coast, owing to the gradual

slope of the bottom for a distance of

thirty to fifty miles, are in many places

not more than from ten to twenty-five

fathoms deep? No wonder that when

sailing-vessels, and even steamers, are

sunk off the Atlantic

coast, their spars

project well above

water—a menace to

every ship that plies

the near-by waters.

In these days of

radio communica-

tion it is not a mat-

ter of great difficulty

to locate a wreck,

and the nearest

available cutter be-

gins search at once.

Even if the wreck is

soon found the cutter

must often “heave

to" and await good

weather conditiors.

‘The handling of gun-

cotton mines and the

necessary detonating apparatus in

small boats, tossed about in rough

water, is not, as may well be imagined,

the safest of occupations. Carefully

the mine is secured to the projecting

‘mast by a bridle, and attached to a

water-proofed electric cable. Then it

is allowed to slip down to the foot of

the spar. Off rows the boat to a safe

distance, One vigorous downward

thrust of the magneto, and there is a

Sol) roar. Hundreds of tons. of sea

water are cascaded upward.

In the midst of the mass

of glittering white

‘water 1s the huge

spar, jerked loose

from its steel

shrouds. Two,

three, four, five,

and sometimes six

times the boat re-

turns and places

‘mines, depending

upon the number

of masts in the

sunken vessel.

Wreckage Must

Be Towed Away

Even when all

the spars are

blown up, the

task of the cutter

is not completed.

Frequently the

wreckage is tan-

gled in steel stays

and shrouds, which must be cut. The

spars are usually lashed together and

towed to shore. ~ After all the spars in

sight have been removed, soundings

are taken over the wreck, and the in-

formation thus obtained is dissemi-

nated to shipmasters through Hydro-

graphic Office bulletins.

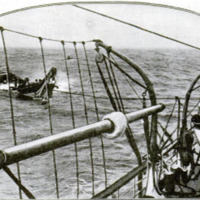

Floating derelicts, although less

‘numerous, are much more difficult to

remove. The records of a decade

show that fully ninety-five per cent

of floating dereliets are lumber-laden,

the timber in their holds keeping them

afloat. Statistics also show that the

stormy waters within a radius of one

hundred miles of Cape Hatteras are re-

sponsible for most floating derelicts.

Two_cutters are stationed in that

vicinity.

At first, attempts to locate these

ocean waifs were not succcessful, but

navigating officers have now evolved

systems of search whereby failure

bas become less frequent. At first it

was the practice to follow a zigzag

course in the direction which it was

assumed the wanderer might have

taken. Searching after this fashion

was mere guessing.

Nowadays the “spiral system” is

employed. A cutter starts from the

position where the derelict was last

sighted, and from that point steers

a series of courses approximating a

spiral curve, the distance between the

convolutions being equal to twice the

radius of visibility, or the distance at

which the object could be discerned

from a lookout in the crow's-nest. In

clear weather, and with portions of the

spars on the wreck still standing, this

radius can safely be taken as five

miles, so that the distance between

the convolutions of the spiral will be

ten miles. Since a derelict must be

sought in daylight, a lineal distance of

about 145 miles can be covered in one

day's crulsing by the average cutter.

In spiral cruising one day's searching

under ordinary conditions will make it

reasonably sure that the derelict is not

within an area of 1522 square miles.

On several occasions this method has

met with success within a few hours.

Derelicts Towed to Port

Floating derelicts, when found, are

not destroyed. In fact, it is almost

impossible to destroy them. To blow

the drifting wreck out of the way is

simply to heighten the danger. Burn-

ing is usually ineffective; the upper

‘works alone are consumed, because the

seas extinguish the flames as they near

the water's edge. There is but one

sure way of removing these terrors

from the seas. They must be tediously

towed to the nearest port.

Most, difficult of all to handle is the

bottom-up derelict which has been

capsized with all sails set. It is hard

to find, because of the small amount of

exposed surface above the water, and

it is still harder to tow, because

there is no place to which to

fusten a tow-line, and be-

cause spars and resist-

ant sails project

from ninety to one

Jundrec and

twenty-five feet

below the water.

The boat crew

must approach

the slippery bot-

tom of the dere-

lit cautiously

to prevent be-

ing dashed upon

it by the sea.

Picking their mo-

ment, they jump

on the upturned

craft and cling to

the keel, the only

projection avail-

able. Even then

they are in danger

of being washed

off by some break-

ing sea. A long

iron strap is fastened to the bottom

of the keel by a number of ten-inch

spikes. At the end of the strap is a

ring through which the towing-line is

secured.

‘Towing is wearisomely slow. As the

coast is approached the masts strike

bottom and break off. Such wrecks

are difficult to get into harbor, and

so they are sometimes grounded and

allowed to wash up on the beach in

an onshore storm. Probably three

fourths of all the floating derelicts

recovered are repaired and put back

into use.

An International Derelict Patrol

For the ten-year period ended June

30, 1916, covering the entire time in

which records of dereliet work have

been kept, 268 derelicts have been de-

stroyed or removed. At the Inter-

national Conference on Safety at Sea,

in session at London in 1913, brought

about by the loss of the Titanic, the

delegates from all the great maritime

powers voted unanimously to invite

the United States to undertake to rid

the entire North Atlantic Ocean of

derelicts. Unfortunately, before the

convention could be ratified by the

several governments involved, the war

broke out, and the international dere-

lict patrol was, temporarily at least,

‘postponed. .

-

Autore secondario

-

C. A. McAllister (Article writer)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1919-02

-

pagine

-

13-14

-

Diritti

-

Public domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by

-

Davide Donà

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)