-

Titolo

-

The difficulties encountered in the development of parachute technology

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Title: Parachuting to Safety

-

Subtitle: Why it is hard to provide the right kind of parachute to save brave men whose flying-machines have been crippled

-

extracted text

-

FOR the same reason that sailors

are not responsible for the adop-

tion of life-preservers and are

notoriously poor swimmers, aircraft

pilots set their faces against safety de-

vices. The parachute is almost as old

as the balloon; yet no aeronaut would

use it except to make farmers at county

fairs gasp in astonishment at the sight

of a man releasing himself from a fire-

balloon, stepping into space, and float-

ing down safely, slowly, and grace-

fully with a giant umbrella.

In the great war of the nations we

saw the first wholesale use of the para-

chute by officers who had been sent

aloft in captive “sausage” balloons to

watch the effect of artillery fire on the

enemy, and who had to jump for their

lives when the hydrogen-filled en-

velope by which they were supported

became a target for incendiary ma-

chine-gun bullets fired from hostile

airplanes. Time and time again, they

had seen a comrade drop from the

clouds with sickening swiftness. They

had seen brave Lufberry un-

strapping himself and leaping

overboard from his ignited craft

after an encounter with a German

armored plane. They had seen

men vainly struggling to right

machines the controls of which

had been shot away. And yet,

they persisted in rejecting the

only form of life-preserver that

could possibly be used.

Reason Behind the Prejudice

Behind this unwillingness to

equip the airplane with an ob-

viously necessary safety device

lie both prejudice and solid

sense. It is one thing to drop

from a balloon or airship with a

parachute—quite another to drop

from a flying-machine. In a

gas-supported craft a man has a cer-

tain freedom of movement, for which

reason the act of ‘stepping over”

is no more difficult than leaping

from a high roof. In an airplane

it is otherwise. Although he can

unbelt hiruself, rise from his seat,

and leap overboard, the problem of

providing him with a trustworthy

It’s Supposed to Work in

Air and Water

David Williams Ogilvie invented i

life-preserver to save a man not only

from being dashed to pieces, but also

from drowning. The aviator is to

wear a “foundation” garment that re.

sembles a one-piece bathing suit, and

over this a double-walled rubber suit,

which can be blown up with air.

Ogilvie thinks that the air will miracu-

lously help to break the fall if the para-

chute should fail to work. The para-

chute (too small to be of any service)

is fitted to a collar and to ribs like those

of an umbrella. Just raise your arms

and the parachute opens. But there

are 50 many things the matter with

Ogilvie's invention that we really can’t

begin to enumerate them all here.

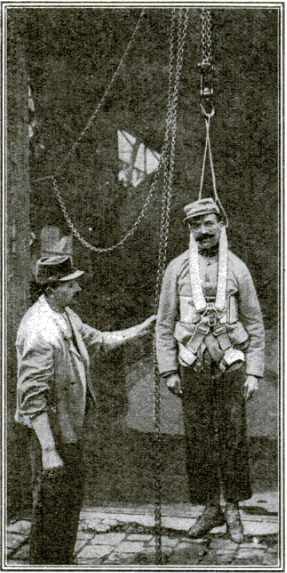

But It's

Only

a Dummy

‘This photograph of

Borer Sos

prod Tae

the cannon has been

automatically fired seems to make out a case

for the Baron; but it is our opinion that he

has not even begun to nibble at the problem.

life-preserver is accompanied with

grave mechanical difficulties. The

parachute” must be extraordinarily

compact when folded; it must be stow-

ed away so that it will not hamper the

pilot; it must not retard the machine

in flight; it must not foul the rigging

at the crucial moment.

Mechanical Difficulties

But this is not all. The flight of an

airplane is mechanically so_different

from the drifting of a free balloon that

Would It Work with a Man?

Baron Odkolok of Paris is here shown ad-

Justing his invention to a dummy seated in a

dummy machine. In the bundle behind the

dummy the parachute is contained. Like

most inventors who have busied themselves

with making flying safe, the Baron thinks that

everything depends on the parachute. releasing

mechanism. He connects the parachute rope

with a small string, and the string in turn

with a little cannon. The aviator unbelts

himself, rises, fires the cannon, and thus re-

leases the parachute. See the picture above.

it may be necessary to jerk the

pilot out of the machine by means

of the parachute itself. When, for

example, the controls of a machine

have been shot away and the ma-

chine drops in a flat spin, the aviator

who has leaped overboard may find

himself overtaken by the plane,

and his parachute torn to shreds

by the propeller.

What of the Peace Machine?

Similar objections might be raised

against the use of life-preservers at

sea. No one demands that a life-

belt shall save an ocean liner's

passenger in every perilous situ-

ation; neither should a parachute

be expected to save an aviator

in the most freakish of accidents.

In warfare, it is true, machines are

shot down from the ground, in which

case there is no chance to use a

life-saver. But what of the peace

machine? What of the thousands of

machines in which zealous young men

learn how to fly? What of the mail-

carrying machines?

How They Land Sometimes

When a balloonist “steps over,” his

heart is in his throat, even though the

parachute has opened with a roar.

Over the battlefield a hostile machine-

gunner in the air may try to pick him

off during the slow descent. And even

though he escaped the machine-gun

bullets, he might find himself dangling

helplessly from a tree in the branches

“of which his drifting life-preserver has

become entangled. ~ Artillery officers

who went up in balloons to observe the

effect of gunfire were taught how to

use the parachute in real schools. Mr.

Calthrop, an English engineer, advo-

cates similar training for airplane pilots.

McLaughlin, an

American inventor,

proposes to have

the aviator carry

the parachute on

his head. We have

taken his idea and

improved it so that

it may conceivably

work. We're not

sure but the aviator's neck would be broken |

when he is yanked out by a parachute that

suddenly opens in the 120-mile gale created

by a swiftly dropping machine, and so we

have attached the parachute sling to the

aviator's shoulder-harness. We would pack |

McLaughlin's parachute in a headpiece, |

streamlined like an airplane fuselage. The

shell forming part of the streamlined para- |

chute bundle falls off when a button is

pressed. The parachute, open as its mouth,

catches the gale created by the falling machine.

A far more valid objection is the

weight of even the lightest parachute.

Let it not be forgotten that an airplane, |

and above all the 120-mile-an-hour

single-seater, is a structure in which |

ounces must be saved; otherwise

it cannot fly high or fast. Clearly,

a parachute weighing thirty or even

forty pounds may not be added |

without lowering the machine's flying

efficiency.

It is obviously difficult to mount

the parachute on a flying-machine of

the pusher type that is, a machine on

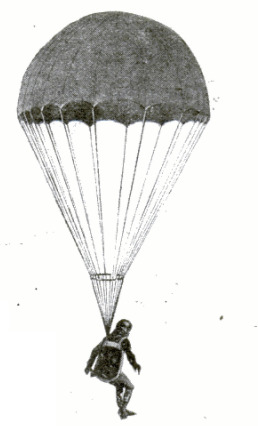

The Way the Germans Did It |

The Germans seem to have been the

first to use the parachute in actual battle. |

Time and time again it was reported that

their airmen were equipped with such acrial |

life preservers. A few of them certainly |

were. Here we have one of their crude devices |

—an_ umbrella folded into pillow form and

attached to the usual aviator's harness.

How well this worked, we don't know as |

yet, because no official reports on the sub-

Ject have been published by the Germans.

‘which the propeller is mounted in the

rear, as in a steamship; for the para-

chute may foul the under-carriage in

the process of opening. With a trac-

tor type of machine, however, the para-

chute can be housed in the rear portion

of the fuselage. All things considered,

the best type of parachute for air-

planes would be one in which the

parachute is launched upward.

Zeppelins Had No Parachute

So far as we have been able to

determine, the Zeppelins were

not provided with any form of

parachute, despite the fact that

it would be far easier to leap

overboard from a giant dirigible

than from an airplane. The

horror of twenty-two men burned to

death two miles in the air, as the result

of a single flaming bullet which has

found its mark in the huge volume of

hydrogen with which the envelopes

are inflated, can be imagined. No won-

der they often leaped overboard in the

hope of finding a mercifully swift es-

tinction below. Even the man in an

airplane that has been crippled has a

better chance of escape than the

stricken members of a Zeppelin that has

been hit; for time and time again air-

planes, by reason of their inherent

stability, have actually reached the

ground in safety, even with their con-

trols shot away.

Will the Parachute Open?

The man who drops from a balloon

with a parachute abandons himself

to a precipitous fall, placing his con-

fidence in the opening of the umbrella

in time to break his fall. Parachuting

of that kind is out of the question from

an airplane, as a general rule. A mod-

ern airplane, even in straightaway

flight, travels at a speed of from 90

to 120 miles an hour. When it

plunges to the ground its velocity is

certainly no less.

Most inventors have failed utterly

to realize what a veritable storm is

created by a high-powered machine,

whether it speeds on normally or

whether it falls like a bullet. They

seem to argue that the whole problem

consists in providing some push-button

releasing device that will free the

aviator and the parachute in a perilous

moment.

The inventor who has unquestion-

ably given the airplane parachute the

most thought, and who has demon-

strated the correctness of his views

most conclusively by the severest im-

aginable tests, is an English engineer,

Mr. E. R. Calthrop. Those who

remember the earlier tragedies of

flying will recall that one of the first

Englishmen to fly was the Honorable

Charles Rolls, whose name is

identified with the Rolls-Royce

car. Rolls bought a Wright

biplane of an early model—a

machine built at a time when

very little was known of the

enormous strains to which sup-

porting surfaces are subjected

in flight. He lost his life in

1910 because of some structural

weakness.

Result of His Friend's Death

Calthrop was a friend of his.

It was the tragie death of Rolls

that impelled Calthrop to concen-

trate his engineering attention on

the invention of a parachute that would

meet the requirements of the aviator.

Calthrop has patented several types of

parachutes. The accompanying illus-

trations picture the details of his most

important designs so clearly that it is

unnecessary to elaborate on them here.

For the immediate purpose, it is suffi-

cient to explain that in its more

To Save Man and Machine

Stick a closed umbrella through the |

‘top of your machine

and the handle into

the mouth of a small

cannon, and you

are applying the

ideas of George

Giem. George has

the gun so arranged

that if the engine

should stop, the

un goes bang! and

the parachute _is

discharged. But

suppose George

shuts off the motor

‘when gliding down?

A locking _ device

prevents the gun

from going off. It

is clear that George

really does not

know” very much

about the problem.

approved form the Calthrop parachute

is folded compactly between two disks,

each about two feet in diameter, and

connected with the machine by a

shock-absorbing sling about fourteen

feet long. The only free fall encoun-

tered is limited to the length of this

sling, and it lasts less than a second.

No Shock to the Nerses

According to Mr. Calthrop, “the

‘whole operation of opening takes only

two and one half seconds, and there is

no shock whatever to the nerves.”

In unfolding, the sling and the par-

achute itself fall outside of thedisks, the

effect being that a cylinder of air is

inclosed so that outside air-pressure

may not prevent the parachute from

opening. Such is the system of pack-

ing that the whole action is progressive.

It was in the autumn of 1917 that

the Calthrop parachute was publicly

tested. An officer leaped from the

top of the London Tower Bridge into

the Thames below—a sheer drop of

175 feet. The test was made for the

express purpose of demonstrating the

possibilities of the invention at low

altitudes. It proved a complete suc-

cess. The actual drop was about 140

feet, which shows that even when fly-

ing very low in an uncontrollable ma-

chine an aviator still has a chance for

his life if he leaps overboard with such

a safety device.

In the present year Captain Sarret

of the French army tested the para-

chute successfully from an airplane

at a far greater height from the ground.

Sarret’s machine was under control of

a pilot. Before the war, however,

Pégoud, who first looped-the-loop in

the air, demonstrated the possibilities

of an ordinary para-

chute—a very much

cruder contrivance

than Calthrop's—by

boldly jumping over-

board with it from a

single-seater.

Such is the rush of

air produced by a

‘modern fast airplane

that even if it were

flying very low—as

‘low, for example, as

twenty-five or thirty feet

from the ground—the para-

chute would still be effective 4

if it is so constructed as to pull

the pilot out of his seat. Indeed,

a man might thus even leave a sixty-

mile-an-hour railway train in safety.

Schools to Teach Parachuting

Mr. Calthrop has urged the need of

schools in which aviators will be taught

how to use the parachute. It is al-

most self-evident that, no matter how

desperate his predicament, an aviator

will try to master his uncontrollable

machine. The parachute is not likely

to be resorted to until it flashes upon

him that it is his one means of salva-

tion. That is not likely to happen

until the machine is within a thousand

feet or so of the ground. Although

Mr. Calthrop has conclusively demon-

strated that his parachute will operate

when it is only a few hundred feet

above the ground, it would be foolish

to maintain that the parachute would

be effective in every desperate situa-

tion, or that it is not more likely to be

effective at greater than at lesser

altitudes. The untrained aviator will

probably be so crazed by the fear of

Kaja T. Togstad thinks this solves the para-

chute problem. The can that Kaja would

have you carry on your back contains a spring

which raises the umbrella when it is time to

jump. The little insert shows Togstad s de-

vice in its inoperative position, when the pilot

is flying along, recking not of shrapnel or

machine-gun bullet. The other picture shows

what happens when the machine is struck .

the fate that is impending that he will

never think of using the one possibility

of escape. Afterall, aviators are taught

at present only to fly, and not

to save themselves in an ex-

tremity. For that reason,

Mr. Calthrop’s suggestion that

parachuting as well as flying

be taught seems to us emi-

nently sane.

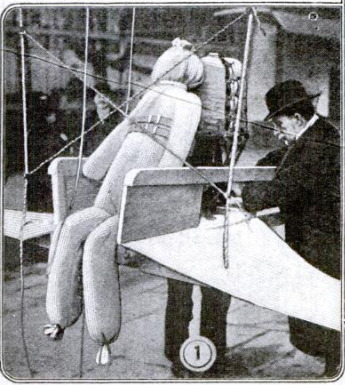

Jerked to Safety

E. R. Calthrop is the inventor of

this ingenious parachute. The rush

of air past a plane, which has made

parachuting seem difficult to most

inventors, is utilized so that the

umbrella must inevitably open in

the precious fractions of a second

that may separate safety from

death. The parachute is packed in

aforwardly inclined container, and connected by a cord and shock- |

‘absorber with the aviator's harness. When a lever in front of the

aviator is pulled, his seat and its back fall into the positions

shown by dotted lines. Compressed air is admitted from a |

reservoir at the bottom of the fuselage to the parachute-container,

and the hinged bottom of the container falls, 50 as to scoop air |

into the container and assist in cjecting the parachute. The |

aviator is actually pulled out of his seat. The parachute is bound

to open instantly, like a sail, and to jerk the pilot out of his dis-

abled craft. Hence the necessity of transforming his seat into |

an inclined launching-way. The invention is evidently designed |

to meet the requirements of those situations in which the machine

is traveling faster than a man can fall, so that he cannot step |

overboard, as from a balloon. It is clearly adapted to the mod-

ern plane, which is quite free from entangling appendages at the |

rear. But will the invention work when the machine is stalled?

-

Autore secondario

-

Waldemar Kaempffert (Article writer)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1919-03

-

pagine

-

44-47

-

Diritti

-

Public domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by

-

Davide Donà

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)