-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

The important role played by British and U. S. artists in the improvement of comouflage systems for ships

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

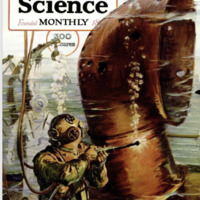

Title: Fighting the U-Boat with Painting

-

Subtitle: How American and English artists taught sailors to dazzle the U-boat

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

ROBIN HOOD was a camoufleur.

Like all huntsmen from time

immemorial, he wore green, so

that he would blend in color with the

foliage of the forest. He must have

been all but invisible when he stood

stock-still. Naval officers would say,

in their technical parlance, that his

visibility was low.

There never was a time, in the his-

tory of warfare, when similar camou-

flaging was not practised in a crude

yet effective way for the purpose of

concealment. Julius Caesar knew the

value of low visibility; for he gave

orders that the ships that bore him -

to Britain should be painted green and

that his sailors should wear green.

‘The Romans camouflaged their ships

when they went out to suppress

troublesome Mediterranean pirates.

And’ the seafaring Danes, too, long

before the Christian era, tied

boughs to their masts and lurked

in forest-fringed bays to mislead

their naval foes i

Battleships have been painted a

dull slate-gray for a generation, to

‘make them less conspicuous; but it

is doubtful if their visibility was ever

aslowasthat of the camouflaged ships

of the ancient Romans and Danes.

At all events, we know now that

battleship paint was neither properly

selected nor scientifically applied.

Artists to the Rescue

‘When the German U-boats began their

depredations, it became desperately

necessary to provide some protective

coloration for transports, food-ships,

and the hundreds of vessels that were

carrying munitions to Europe.

‘Battleship gray having proved utterly

useless, naval officers turned instine-

tively to artists for advice and assis-

tance. If an artist, with his trained

eye, knows how to apply color, knows

how to trace lines on canvas so that

they become the counterfeit present-

ment of the thing he sees, couldn't

he reverse the process and devise

some way of blotting out the thing

to be looked at?

It s0 happened that American art-

ists interested themselves in devising

schemes of protective coloration as

soon as the U-boat began to sink on

sight. The pioneers among them were

William Andrew Mackay, Maximilian

Toch, Gerome Brush, E. L. Warner,

and Louis Herzog.

These artists relied almost entirely

on their experience as observers of

nature and colorists; no attempt was

made at first to approach the subject

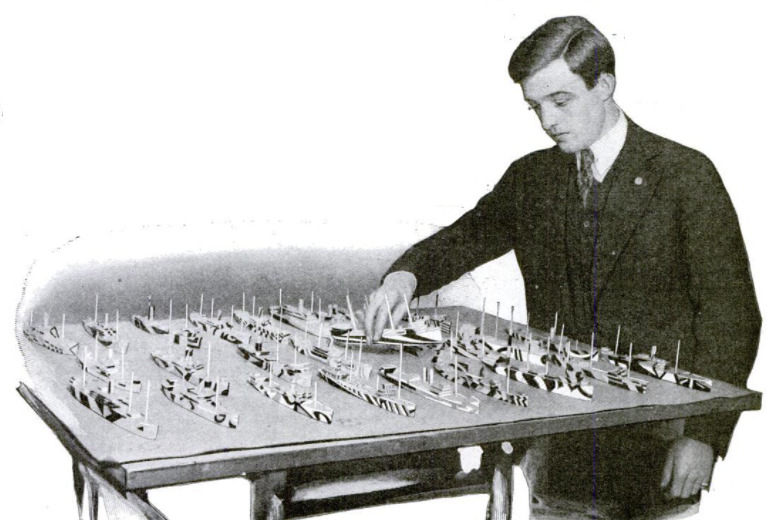

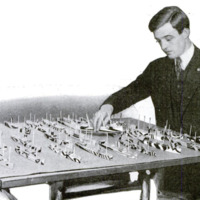

Standardizing Marine

Camouflage .

In1917the Submarine Defense

Association was formed for the

purpose of laying down the

principles of marine camouflage

and standardizing them as far

as possible. The association was

composed of nearly a hundred

leading American and British

shipping and export companies

and all the leading marine

insurance firms. Lindon W.

Bates was made chairman of the

Engineering Committee, and

through him Mr. George East-

man became interested to such

an extent that the resources of the

Kodak Laboratory were placed at the

commistee’s disposal so that camouflage

could be studied scientifically.

The first inkling that ship-owners and

the general public received that the ap-

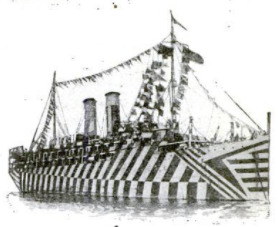

parently crazy splashes of paint and

the freakish stripes that adorned the

smokestacks, superstructure, and hulls

of ships were not the whimsical color

schemes of half-demented cubists and

futurists, but very carefully thought

out systems of protection, came in an

order from the War Risk Insurance

Board to the effect that ships not

camouflaged according to the principles

laid down by Mackay, Brush, Herzog,

Toch, and Warner would have to pay a

higher premium for marine insurance.

The committee provisionally accepted

the work of these five men as a basis,

and then proceeded tostudy camouflage

not from the artistic but solely from a

dispassionate scientific point of view.

U-Boat Commanders Baffled

For a time low-visibility coloration

baffled the U-boat commanders. It

had its limita-

tions. Effective

enough at dis-

tances of 5,000 yards or more, it failed |

to protect at shorter ranges. More-"

over, U-boat commanders were not

dependent on their eyes alone; their

craft were equipped with microphone

sound-detectors—sensitive instruments

that made audible the beating of dis-

tant propellers, the thumping of en-

gines, the thousand and one murmurs,

raspings, and clankings of a laboring

ship. Even if the U-boat captains

eyes were momentarily fooled, his

electrical ears were hearing.

Then it was that Mr. Mackay and |

Commander Norman Wilkinson, the

distinguished English marine artist,

independently began to experiment |

with the idea of throwing the U-boat |

commander off the track.

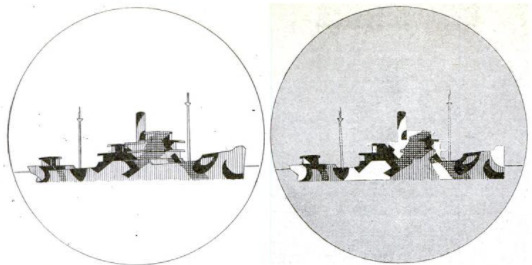

The man at the periscope has to sight

and to take very careful bearings be- |

fore he can plant a torpedo success-

fully. He launches his torpedo at a |

range of less than a mile, as a rule. |

Is it not possible to fool him as to the

direction in which the ship is heading,

or as to the part of the hull at which

he is looking? That is the underlying

principle of what is known as the

“dazzle” system. It is now combined

with the low-visibility system; for

low visibility has advantages

at ranges of more than 5,000

yards.

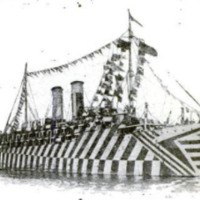

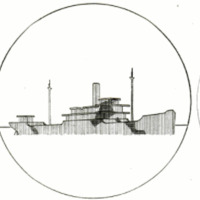

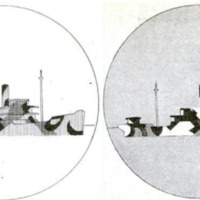

The ** Dazzle” System

The dazzle system is really

an evolution of the low-visibility

system. It was discovered that,

while large patches of color

serve to break up the char-

acteristic lines of a ship, smaller

patches are even more effective.

Small patches, in turn, sug-

gested stripes, and striping is

the basis of some “dazzle” for-

mulas. Low-visibility painting

and dazzle painting are really

antagonistic in principle. The

one is most effective at long

ranges, the other at short ranges.

Low visibility is of primary import-

ance; dazzle painting is of use only

at fairly close quarters after low visi-

bility has failed. Low visibility is in-

tended to prevent an attack from being

made at all—the dazzle system to pre-

vent the attack from being successful

Low visibility is always of primary im-

portance, because it complicates the

U-boat’s task.

Suppose an uncamouflaged ship is

visible at 15,000 yards. Skilful camou-

flaging will enable her to approach the

seeing eye to within 5,000 yards

without increasing her visibility, In-

terpret this fact in terms of the sub-

marine. It means that more U-boats

must patrol a given area traversed by

camouflaged than by uncamouflaged

ships.

The area of a circle varies as the

squares of the radius. Hence, if a

camouflaged ship can steam safely at

a distance of 5,000 yards and an un-

camouflaged ship only at a distance of

15,000 yards, the area that a U-boat

can effectively patrol is only one ninth

as great if it is hunting for ships of

low visibility. Nine submarines must

patrol the area that could otherwise

be covered by one. On the whole,

more reliance is placed on the attain:

ment of low visibility than on dazzling

painting.

But, at Teast, dazzling the U-boat

commander has this advantage. If

he does not score a hit, he is sure to

be run down or sunk by gun-fire when

he comes up to find out whether or not

he wassuccessful. He betrays himself.

What Constitutes “Appearance” >

Look at that horsé walking down the

street. You recognize him at once as

a horse, even though he is a quarter

of a mile away. And why? Because

of his general appearance, you say.

But what constitutes “appearance”?

Form and very little else—a peculiar

arrangement of lines, curves, and

angles. If you paint a picture of him

you sketch on your canvas these lines,

curves, and angles.

Out at sea is a ship. Like every-

thing else in the world, she is to the

eye a combination of lines and angles.

In which direction is she heading?

North-northwest, you say. How do

youknow? You judgethe course chiefly

by the motion of the superstructure,

a thing that bears a certain angular

relationship to the hull. Destroy these

angles, or substitute others for them.

The angles by which we judge rela-

tive motion are not those to which

our eyes have been accustomed; the

ship seems to be heading in a direc- |

tion that is not her real course.

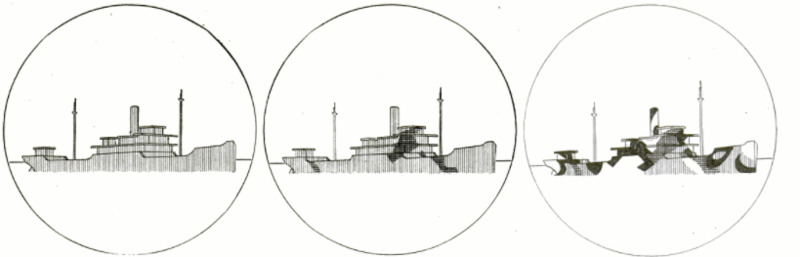

Look at such a ship through the

periscope, and you will be dazzled—

dazzled not in the sense that you

find it painfully difficult to see, but

in the sense that you are deceived. An

error of a few degrees in course, of two

knots in speed, or of two hundred to

three hundred yards in range is enough

to throw out the aim of the man who

gives the signal to launch a torpedo.

Tt was the task of the Submarine

Defense Association to determine

whether low visibility was better than

dazzle, or vice versa; whether low

visibility should be combined with

dazzle or-not; and how the different

low visibility systems compare with

one another and likewise the different

dazzle systems.

Scientific research proved that every

dazzle system surrenders something fo

visibility. How much may thus be

safely sacrificed in order to throw out

the torpedo can be determined only af-

ter along and patient scientific investi-

gation. It seems certain, however, that

dazzle painting on bows, funnels, and

‘masts is very effective, the result being

a confused pattern which usually de-

ceives as to course, range, and speed.

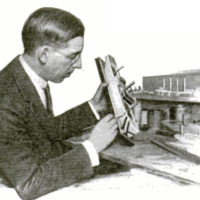

Enter the Scientist

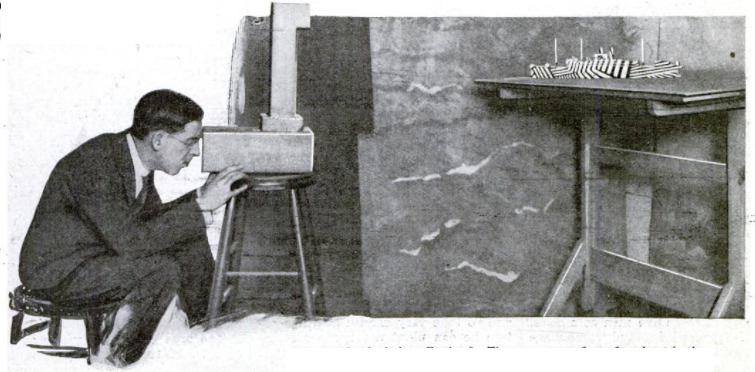

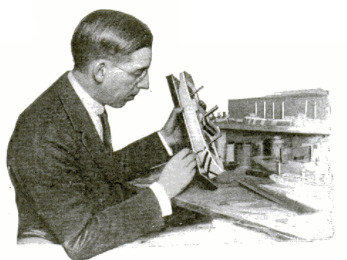

The first scientific study of marine

camouflage has been made by Mr.

Lloyd Jones, of the Eastman Kodak

Laboratory. He invented a visibility

meter in order to pursue his investi-

gations. His dispassionate examina-

tion shows whether or not the particu-

Tar shade of violet or green selected

is scientifically the best, or how

one dazdle: vation comuares with

another, The artist,

having laid the foun

dation, gracefully re- |

tires and leaves the |

refining of marine

camouflage to the |

physicist.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Waldemar Kaempffert (Article writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1919-04

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

17-19

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Davide Donà

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Popular Science Monthly, v. 94, n. 4, 1919

Popular Science Monthly, v. 94, n. 4, 1919