-

Titolo

-

The improvements in radio-telephony and its importance for the communication

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Title: Flying a Mile High, He Hears You Speak

-

Subtitle: How the radio-telephone now links the airman with the earth

-

extracted text

-

WHEN suifutoiog V of deven

‘monoplanes soared into the

view of Colonels Reber and Culver at

the 1910 Belmont Park Aviation Tour-

nament, the same thought, oddly

enough, came into both their minds and

was _expressed by Colonel Culver:

“What a splendid thing it would

be in battle if those eleven planes

could be instantly commanded by

their leading pilot! What could be

done with the control of every

evolution from the air or from the

ground, and with each pilot receiv-

ing instructions from moment to

moment!”

Tt is easy even for civilians to see

what this would mean. Directions

given before the flights began, as

conditions changed with the sud-

denness of war-time needs, could be

changed, and each flier could be

told just what to do in a mass

attack on the enemy. As the two

colonels looked back to the wireless

telegraph work that had already

made it possible for pilots to report

‘observations to ground stations miles

away, they determined that this

ideal ‘of a voice-commanded squad-

ron of airplanes should be realized.

What Has Happened Since

In five years the telegraphic branch

had been developed to a point at

which airplane communication was

demonstrated over one hundred and

forty miles at the flying school near

San Diego. In another year it was

possible to telegraph in both directions

between airplanes in flight, without

serious interference from the noises of

wind and motor exhaust.

Early in 1917 the wireless tele-

phone was used to talk from the air

to the ground, and in October of

that year experimental radiophone

outfits for squadron flying were taken

to France for demonstration by Col-

onel Culver.

A year later Major-General William

L. Kenly and Director John D. Ryan,

in charge of the air program of the

nation, announced that the voice-

commanded squadron was a reality,

and that, since the signing of the

armistice had removed the need of

secrecy, its effectiveness could .be

shown to the public.

Demonstrations in Washington, at

which President Wilson and Secretary

Baker were present, banished the last

doubts as to what had seemed an im-

possible dream only six years before.

At one of these demonstrations the

President, standing on the White

House lawn, gave a command to dive.

Immediately a swift de Haviland,

flying overhead, nosed toward the

earth at increased speed until, at the

words “Flatten out,” it turned into

the horizontal and sped on in a great

Magic of Wire Telephony

In wireline telephony we know

that the vibratory sound-waves of

the voice strike against the dia-

phragm of a transmitter, causing

this diaphragm to vibrate in a

similar way. The mechanical

vibrations compress and release a

capsule of carbon granules fastened

immediately behind the diaphragm,

and the variations in pressure create

variations in the resistance, which

the granules oppose to the flow of

an electric current through them.

The intensity of the constant stream

of current generated by a battery

or dynamo, and passing through the

granules, is thus varied in accord-

ance with the voice vibrations.

This fluctuating current is led along

the line wires from the transmitter

to the distant station, and there is

applied to a telephone receiver.

The receiver contains a diaphragm

which is moved magnetically by the

incoming currents, and which vibrates

at a speed and intensity governed

by the variations in the currents. Since

these current-vibrations are similar

to those of the voice at the transmitter,

the receiver-diaphragm vibrations that

they produce are also similar. Conse-

quently the receiver re-

creates sound-waves similar

to those generated by the

voice at the sendingstation,

andthe listener hears a re.

production of the words as

they are spoken into the

transmitter. Although a

number of simultaneous

operations are involved, the

action is evidently not at

all complicated.

Analogous to Wire

Transmission

For transmitting the

voice by wireless an entirely

analogous set of conditions

exists. The main and

obvious difference is that

there are line-wires to con-

duct the continuous stream

of voice-carrying electric

current from the trans-

mitter to the receiver.

Some other way of con-

veying the voice-controlled

vibrations must therefore

be found; and in radio-

telephony this part of

the communication sys-

tem is based upon the

properties of electromag-

netic waves in the so-called

ether of space. Just as a

candle radiates light-waves

in all directions, so a suit-

able radio-generator will

radiate streams of elec-

tromagnetic waves to dis-

tant receivers in any diree-

tion. Having at hand such

effective carrier-waves to

transport signals from point

to point through the air,

whether on the earth's

surface or above it, all that

remains in order to trans- |

mit speech by wireless is

to devise suitable appara-

tus for the sending and

receiving stations.

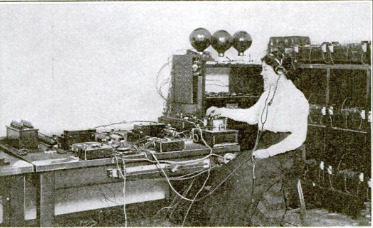

The wireless transmitter,

like that of the wire tele-

phone, contains a dia-

phragm and a capsule of

carbon granules. However,

instead of merely varying the intens-

ity of a stream of current passing out

over wires to the receiver, the radio-

transmitter varies the strength of a

continuous stream of electromagnetic

waves, these being radiated into space

in all directions from an aerial wire.

A portion of these waves necessarily

reaches the distant receiver, and there

is caught by a similar aerial wire in

which the waves induce high-frequency

varying currents. These currents are

then led to the receiving apparatus,

by which they are first converted and

magnified, and then applied to a tele-

phone instrument in which they re.

produce the sounds spoken.

Imagine a fleet of airplanes in which

each is equipped with a complete

radio-telephone transmitter and re-

ceiver. The pilot of the commanding

airship can control his squadron in-

stantaneously by his spoken orders;

the group can act in unison for attack

or defence, and movements of enemy

airplanes or forces detected by any

observer can be immediately described

to all the others.

Some of the Difficulties Overcome

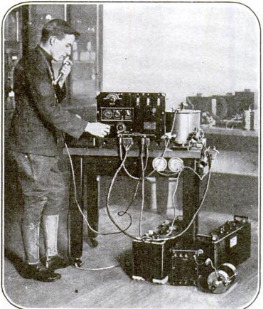

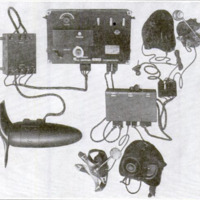

The manufacture of a suitable hel-

met that would exclude the terrific

explosions of the 400 - horsepower

Liberty motors (which are

invariably used without

‘mufling-chambers) was only

less difficult than the pro-

duction of a good trans-

miter.

When one considers how

the ordinary telephone picks

up the noises of passing

trolley cars or trucks, it

is easy to appreciate the

amount of work that was

required to make a micro

phone which was marvel-

ously sensitive to the human

voice and yet scarcely af-

fected by the thunder of

the motors or the rushing

of the wind.

Another knotty problem

‘was the arrangement of the

aerial wires so that they

would not trail far behind

the airplane and become

entangled when loops or

dives were performed, or

when the other airplanes

of the flying squadron ap-

proached. This was solved

by the use of short un-

weighted wires dragging

from the wing-tips, rather

than the long single cable

that was first utilized, and

which suspended a lead

weight some three hun-

dred feet below and behind

the airship.

Future A the Radio-

Telephone

It is difficult to foresee

‘the future of airplane radio-

telephony, for its greatest

value is doubtless in cone

nection with group flying.

But the day of the com‘mercial airplane seems

dawning. When

‘groupsof airplanes

travel together

from city to

city, their pas-

sengers willsurely appre-

ciate theradio-

telephone.

-

Autore secondario

-

John Vincent (Article writer)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1919-05

-

pagine

-

54-55

-

Diritti

-

Public domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by

-

Davide Donà

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)