-

Titolo

-

Methods for raising sunken ships and submarines

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Title: They bring 'em back afloat

-

Subtitle: Our navy can raise ships as well as sink them!

-

extracted text

-

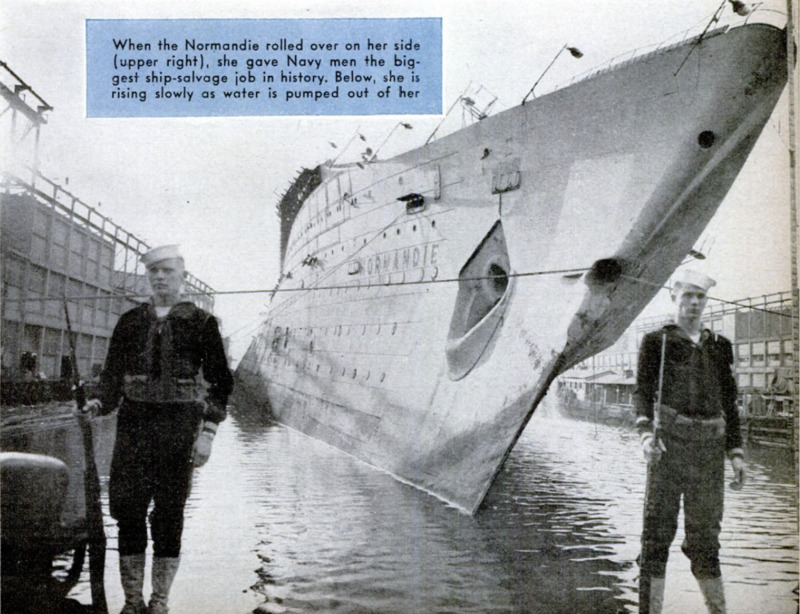

FIVE million dollars represents the ap-

proximate cost of five Liberty ships, a

single day’s launchings. It also happens to

be about all that Navy salvage in U.S.

coastal waters has cost since the beginning

of the war, not counting the Normandie.

But this second five million has paid a

return, in the salvaged values of hulls,

cargoes, and supplies rescued from the sea,

estimated at over $400,000,000. We say

“estimated” because the sum grows every

day and because the Navy isn't saying too

much about some of the phases of Navy

salvage’s world-

wide activities, the greatest and most far-

flung salvage work of all time.

Since 1941, when Congress passed a law

permitting the Navy to salvage both public-

ly and privately owned ships, we have heard

a lot about some phases of this work: the

raising of the Normandie and the refloating

of the battleships in Pearl Harbor. But most

of the work has been done quietly, either to

prevent enemy interference and bombing of

work in the war zones, or because there was

no need to inform Hitler and Hirohito that

ships they thought safely sunk are again

carrying cargoes for the United Nations.

The Navy salvage chiefs, whether they

work in Eritrea or in the Solomons, in the

fog-bound Aleutians or en route to Mur-

mansk, must always work pretty much on

their own. Every salvage job calls for

quick, flexible planning and ingenuity in

devising salvage methods.

All salvage jobs, however, fall into a few

general classes. The trick is to adapt the

standard salvage methods to fit each new

task.

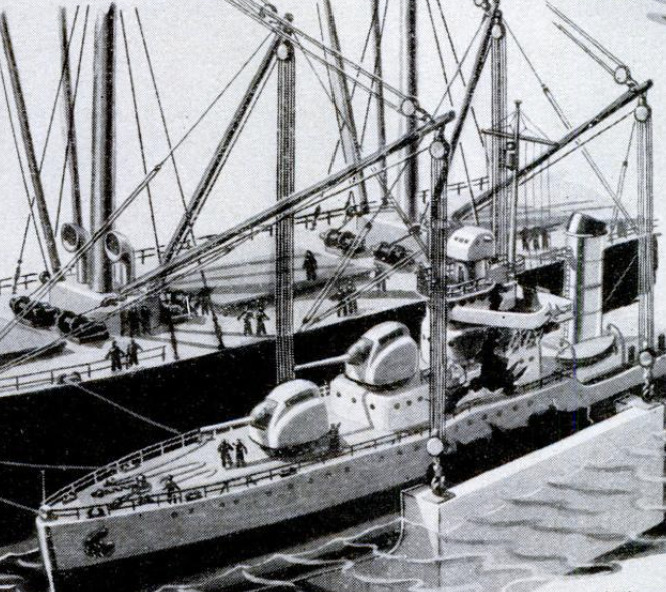

One of the largest classes, in terms of

tonnage saved, is that of ships

which, are disabled but not

sunk. Here salvage in the

Navy begins the moment a

ship is hit, when repair parties

explore the damage and try

to limit it. They shore up weak

bulkheads, patch small holes,

pump out compartments, and

restore or improvise hose and

communications lines, so that

the ship can, if possible, get

under way again.

When the injuries are so

great as to prevent the ship

making way under its own

power, towing is resorted to—

a tricky and dangerous job in

heavy and icy seas with enemy

subs always presenting an added element

of danger for both the injured ship and the

rescue vessel. Once towed into harbor, a

disabled ship can usually be repaired and a

very high percentage of its value recovered.

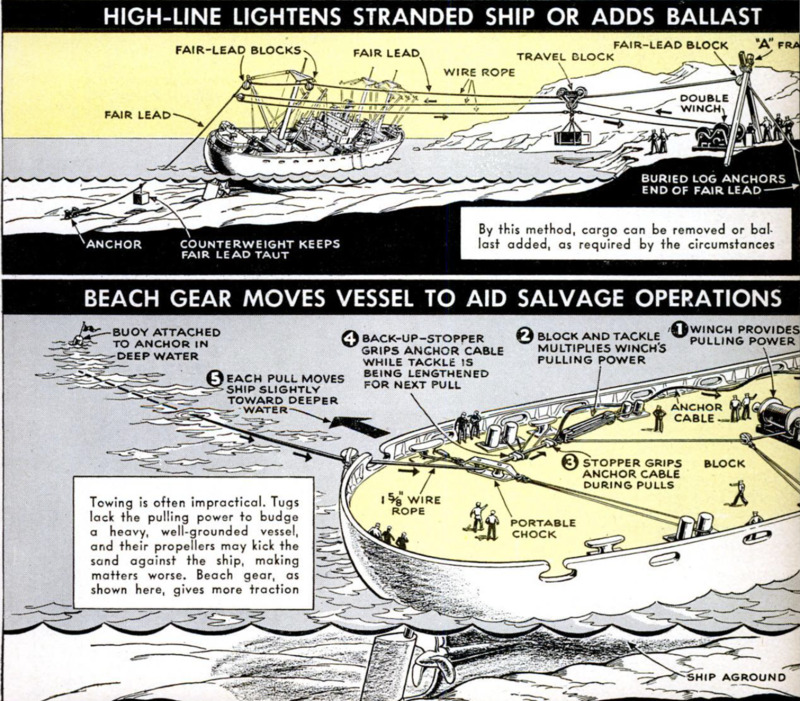

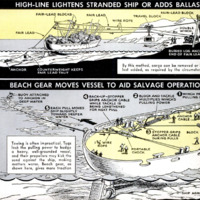

Stranded ships fall into an in-between

class. In wartime, these are often ships

that have been deliberately run aground to

prevent their sinking. Hence they may have

great holes in their hulls, which must be

repaired or temporarily patched in an angry

surf before the ships can be refloated. In

such cases, the most obvious things are usu-

ally the worst things to do. The amateur

would think that discharging ballast and

cargo would lighten a ship and permit her

to float off. But usually, when this has

been done, rough seas have heaved the ship

farther ashore and either completed the

wreck or made salvage far more difficult.

The skilled salvage man, therefore, first

tries to make his ship stay put. He adds

ballast. Then he runs out beach gear, set-

ting anchors a few hundred feet from the

ship. Usually he plays safe and sets these

to all four quarters, until he can get a

chance to study the lay of the bars or

reefs and decide which is the best direction

in which to haul off.

Another bright thought of the amateur

is towing. If a ship is very, very lightly

aground, towing might help in a rising tide

and a calm sea. But whenever conditions are

bad—and they usually are—towing may

make things worse instead of better. A

10,000-ton vessel may be resting 1,000 tons

of its weight on the ground. Three hundred

to 500 tons’ pull will be required to over-

come friction in pulling 1,000 tons along the

bottom. And the biggest tugs seldom have

a pulling power of over 15 tons, because they

must gain all their power through the pull

of their propellers in the water. What

usually happens is that the tug stays put

on the end of its cable and its propellers

churn up the sandy bottom and send it

against the hull of the ship, making the

task harder. With beach gear and anchors,

a much greater pull can be ex-

erted.

Tugs can be useful, though,

in refloating a stranded ship.

One way they are used is to

scour the silt and sand away

from the ship's hull, by the ac-

tion of their propellers. Sometimes they

tie themselves by the bow to the stranded

ship and thus dredge a channel through

which the ship can be hauled into deep

water. High-pressure hose lines are often

used to remove silt or to form working

channels alongside of stranded or sunken

hulls, when patches are to be applied to the

sides or bottoms.

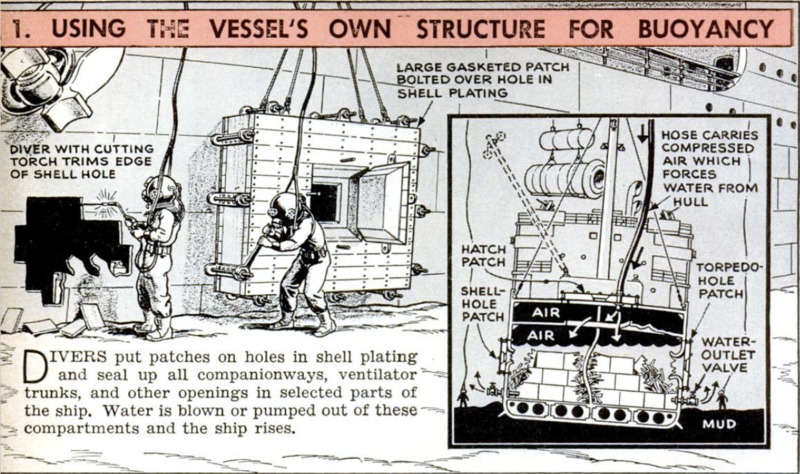

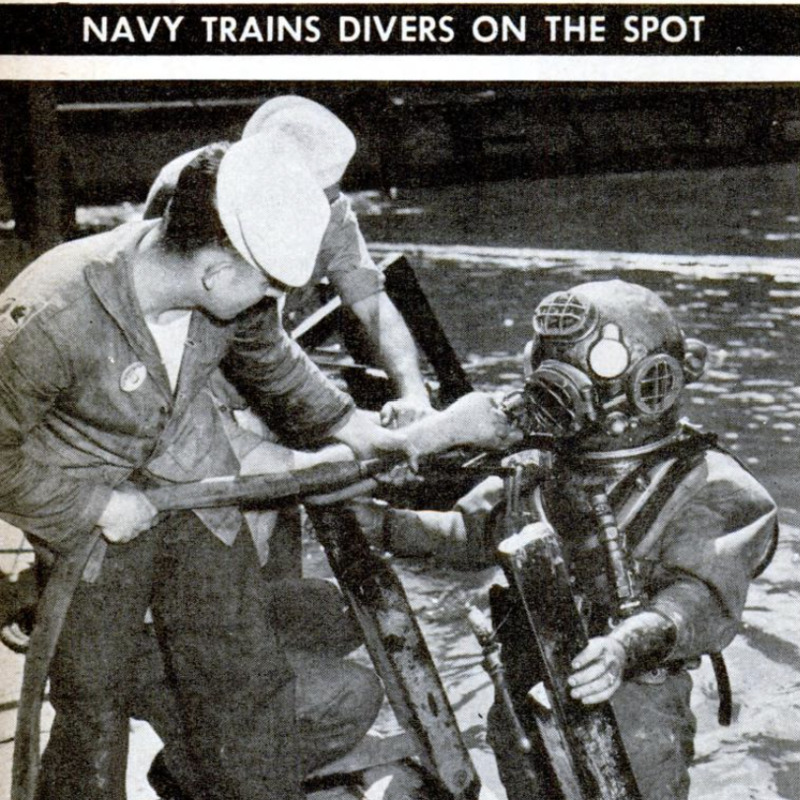

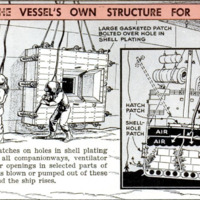

By far the most spectacular sort of

salvage work, however, is that in which

sunken ships are raised. One method uti-

lizes the ship's own structure to attain

buoyancy. Divers go down and explore the

hull, locating all holes and measuring them.

Then the engineers decide which holes must

be plugged up or sealed to make pumping

or blowing possible. Since modern ships are

divided into compartments, it is not neces-

sary to seal all openings under water.

Many can be left to later work after flota-

tion and docking.

The choice of pumping or blowing de-

pends on circumstances. Pumping is ac-

complished with ordinary large-capacity

gas-driven pumps or with electric under-

water pumps. Blowing involves the use of

great air compressors on the salvage ves-

sel, which force air down through hose

lines and thus blow the water out of chosen

compartments. When a sufficient number of

compartments have been blown free of

water to restore buoyancy to the vessel, it

rises to the surface.

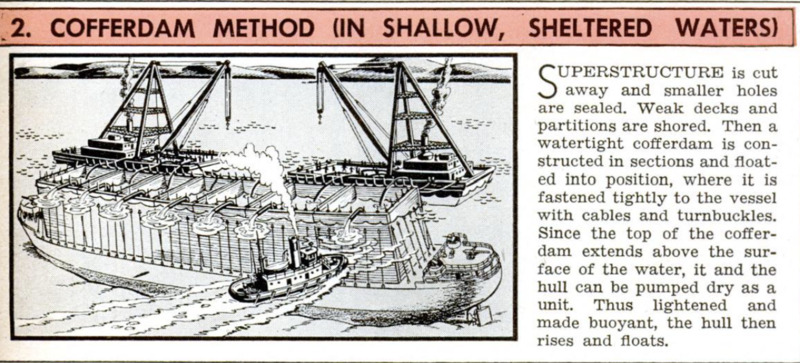

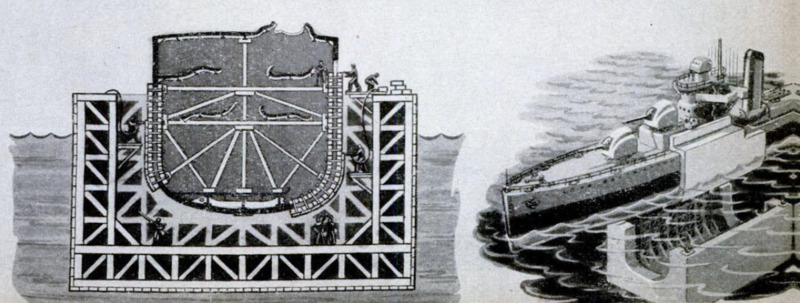

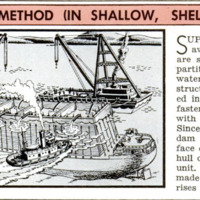

For ships in relatively shallow water and

in protected bays and harbors, the coffer-

dam method offers some advantages. This

method involves building up a ship until it

stands clear of the water at high tide. If

this can be accomplished, the water can be

pumped out of the combined structure —hull

and cofferdam—very much as if a giant

bailing operation were being carried on.

The cofferdam itself may be built around

the whole hull or around selected deck open-

ings, such as cargo hatches. The structure

is usually built in sections ashore and

floated or carried on barges to the wreck.

Floating derricks aid in setting it in place,

while divers secure each section to its cor-

responding portion of the ship, using cables

and stays and turnbuckles until they achieve

a watertight joint.

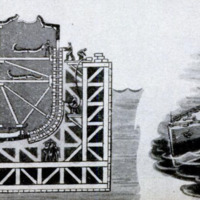

While both the cofferdam and seal-and-

pump methods involve the restoration of

buoyancy to the ship itself, this cannot al-

ways be accomplished economically. Ships

sinking in deep waters—subma-

rines, for example—are often

too difficult to work on for the

long periods these methods re-

quire. Therefore, salvagers fall

back upon a modernized version

of one of the earliest salvage

methods. This involves the use of large |

cylindrical pontons—great tanks that can |

be submerged alongside of the wreck. Once

attached, they are pumped or blown clear

and thus float the wreck to the surface in

a single stage. The method is ideal for the

raising and relocation of relatively small |

wrecks lying at substantial depths.

Curiously enough, some of the jobs that

look the hardest are actually easier than |

some others. A floating dry dock, for in-

stance, seems to present the most difficult

of all salvage jobs, especially if it has been |

effectively scuttled. However, a dry dock |

is a vessel originally constructed for great

buoyancy. It must float both itself and

another vessel. Thus, to raise the dry dock

alone requires the sealing off of only a few |

of its many compartments. |

The decks and bulkheads of a floating dry |

dock also are built to much higher stand-

ards of strength than are those of most

ships, for the decks must support the weight

of great ships, and the bulkheads must with-

stand water pressures in the process of sub-

mersion and flotation, which is the dry dock’s

way of working. Hence, salvage of such a

vessel may actually prove easier than the

lifting of a much smaller hull. |

By no means all sunken or derelict ships

can be salvaged, even in peacetime. Four

hundred feet is almost the maximum depth

at which any work at all can be carried

on; most salvage work is done at much

shallower depths. Many ships that sink

even in shallow waters are simply blasted

away as dangers to navigation, since their

value “as they lie” does not sufficiently

exceed the cost and risk of the salvage

operation they would require.

Despite these limitations, Navy Salvage

does not lack for work. Before the war is

over, it will have restored well over a

billion dollars’ worth of ships and cargo to

the United Nations, and that figure is based

upon value after salvage. The true worth of

Navy Salvage cannot, of course, be esti-

mated, for it must include the immeasurable

value of having cargo vessels and combat

ships now, which could not be built new ir

our capacity-taxed shipyards. In that sense,

the hulls that rose out of the mud at Pearl

Harbor, and countless others, are “finds,”

ghost ships rebuilt to better-than-before

fighting power, now hitting back at the

enemy that treacherously sent them to the

bottom. —ALBERT Q. MAISEL.

-

Autore secondario

-

Albert Q. Maisel (article writer)

-

Stewart Rouse (illustrator)

-

Robert F. Smith (photographer)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1944-01

-

pagine

-

96-102

-

Diritti

-

Public Domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by

-

Lorenzo Chinellato

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Immagine 2022-04-09 130813.png

Immagine 2022-04-09 130813.png Immagine 2022-04-09 130905.png

Immagine 2022-04-09 130905.png Immagine 2022-04-09 130928.png

Immagine 2022-04-09 130928.png Immagine 2022-04-09 130946.png

Immagine 2022-04-09 130946.png Immagine 2022-04-09 131018.png

Immagine 2022-04-09 131018.png Immagine 2022-04-09 131114.png

Immagine 2022-04-09 131114.png Immagine 2022-04-09 131140.png

Immagine 2022-04-09 131140.png Immagine 2022-04-09 131207.png

Immagine 2022-04-09 131207.png Immagine 2022-04-09 131244.png

Immagine 2022-04-09 131244.png Immagine 2022-04-09 131311.png

Immagine 2022-04-09 131311.png