-

Titolo

-

The important role played by the American telegraph in the Western front during World War I

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Title: The American Telegraph in France

-

Subtitle: It did its part in overthrowing Berlin

-

extracted text

-

HAD the great war lasted one more

year or even a few months

longer than it did, America would have

had completed and in operation a

system of modern land-line telegraphs

‘throughout the length and breadth of

France not held by the Teutonic

forces. This had to be done. The

French government telegraphs, of the

open-circuit variety, still universally

employ the antique tape-recording ma-

chines such as we threw into the rub-

bish heap in the first days of the Civil

War; “bluestone” and sal ammoniac

cells have not yet been supplanted by

the dynamo, nor does the typewriter

figure in the game of the wires.

The slowness, sluggishness, and in-

efficiency of the system during hos-

tilities was astounding. The British

government railed and fumed and

fussed about it. One high official even

went so far as to complain publicly, and

in the course of his remarks expressed

no surprise that the “Big Berthas"

still thundered at the trembling gates

of Paris as they had thundered for four

crimson years.

John Bull kicked, M. Poilu shrugged

his shoulders; but the old tape ma-

chines continued to take their time

in negotiating the most vital messages.

Entered then the Yankee. Ho

fussed not; neither did he hesitate or

postpone. His doughboys in khaki

and his gobs in blue laid aside their

shooting-irons, their gas-masks, and

their military dignity, shouldered picks

‘and shovels, strapped on pole-climbers,

grasped_comealongs, puckered their

ipa to the tune of “Dixie,” “Yankee

Doodle,” or “Madelon,” and made the

fur fly along the turnpikes and rail

highways of France from Brittany to

the Hindenburg line, and from the

shores of the English Channel to the

frontiers of Spain.

‘Telegraph construction work is es-

pecially difficult in the western part of

France, due to a rather thin soil in

places, and wolid rock beneath into

which post-holes have to be blasted.

But these boys, disdaining fatigue,

anubbing holidays, scorning those

rocks, carried the work ahead so

rapidly that soon the main arteries

were completed. Dig, sturdy Ameri-

can Morsemen, skimmed from the

cream of the profession in the home-

land, ofled up their typewriters and

their sending arms, American relays

sputtered, American sounder clicked

and clattered, and John Bull ceased

complaining, ‘while M. Poilu let his

Tower jaw fall in blank wonderment.

One of the main faults of the French

telegraphs is the scarcity of apparatus

for automatically repeating from one

line into another. Apparently they

prefer to do this by hand. Their cir-

cuits are necessarily shorter than ours,

0 that long-distance telegrams are ro-

layed by hand a number of times while

en route, and their transmission fs

delayed accordingly.

To defeat those well-nigh fatal

delays, automatic telegraph repeaters

were installed in the more important

base offices by the A.E.F., the type of

apparatus selected for the work being

that now used almost exclusively by

the American Telephone and Tele

graph Company, but which are little

known as yet by the telegraph frater-

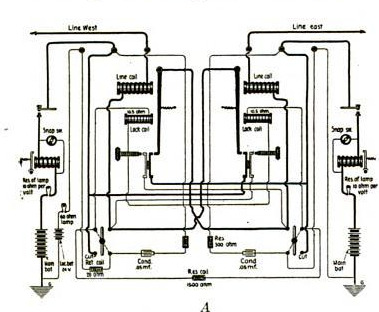

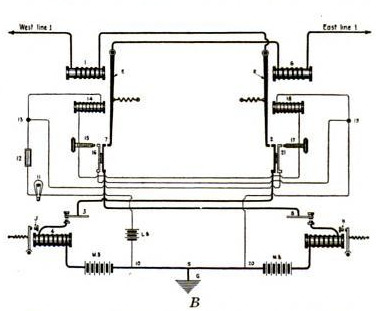

nity at large. Diagram A shows the

actual connections, and ‘Diagram B

‘shows the theory as simply and plainly

as possible. It is the latter drawing

that we shall follow in our description.

‘The heavy lines in the diagram indi-

cate the routes of the mainline con-

nections, while the thin lines trace the

‘secondary eireuits.

When at rest there are currents

flowing through both the east and the

‘west lines; their line coils, Nos. 1 and

6, are magnetized, holding their re-

spective relay tongues to a close.

‘Should a distant office on the west

line desire to “send.” his first action is

to open his key. Tnstantly line coil

No. 1, and the local relay coil, No. 4,

demaguetize, allowing their respective

tongues to fal buck.

"Tho east line, entering the apparatus |

through line coil No. 6 and relay

tongue B, becomes. disconnected at.

contact No. 1, when that tongue {alla

back, so that the eas line goes open in

sympathy with the weet. Now, when

the cast line thus opens, the line coil §

becomes demagnatized, und wero i not.

for the litle secondary call, No. 18, the

relay tongue # vould fal back, break:

ing circuit at contact No. 2. Should

this actually occur, both contacts, No.

7 and No. 2, would be open, rendering

it an impossibility for either the east or

the west to restore the lines to a normal

‘close again.

The tongue F must be kept closed

While the west “sends,” so that the

latter may at all times enjoy an un-

broken pathway through contact No. 2.

AB and DC are uprights of spring

steel, each pair being connected by an

insulating medium (indicated by di-

agonal lines in the diagram), so that

they move in unison.

When the contact No. 7 is opened

through the demagnetization of the

coil INo. 1, the springs DC, no longer

held to the left by tongue E, open con-

tact No. 16. At this instant, and

before the tongue F' has had time to

sever connection No. 2, the current

from local battery LB, ascending to

contact No. 13, has had two pathways

to choose. It may either travel la-

boriously through the coil No. 14,

through 15 and 17 to coil 18, magnetize

that coil in turn, and then meander on-

ward through 19, 20, and 5 to the

ground; or it may, and does, take the

far easier road by disdaining coil

No. 14 entirely, parting company at

13, and making for the ground through

the one coil No. 18. The latter coil

now being magnetized, the tongue F is

held to a firm close at contact No. 2,

even though there is no current

flowing through line coil No. 6.

When the western operator closes

his key to carve out his first signal, the

contact No. 2 being unbroken, the

entire apparatus falls back as it was in

the beginning. The western current

‘magnetizes coil No. 1, jumps through

tongue F and contact No. 2, through

key No. 3, magnetizes local relay No. 4,

picks up more battery, and jumps to the

ground from 5. When coil No. 1 is thus

magnetized, tongue E closes contact

No.7, again closing the east line through

key No. 8, local relay No. 9, adds

the battery, and goes to the ground.

Should the east open to send to the

west, the action heretofore described is

simply reversed, the action of the

secondary circuit being as follows:

The local current reaches 13, but is

prevented from jumping to the ground

through coil No. 18, because contact

No. 21 opened when, due to the de-

magnetization of coil No. 6, the tongue

F fell open. The local current then

has no choice other than to continue

onward from 13 into coil No. 14. This

coil it magnetizes, holding tongue E to

a close. As the tongue E is closed, the

spring contact No. 16 is also closed,

affording a pathway for the local cur-

rent after it leaves the coil No. 14,

through 15, 16, 19, 20, and 5, to the

ground.

In practice there are switches, re-

sistances, condensers, ete., as pictured

in Diagram A, the various uses of

which are obvious.

-

Autore secondario

-

Samuel W. Beach (Article writer)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1919-05

-

pagine

-

84, 86

-

Diritti

-

Public domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by

-

Davide Donà

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)