-

Titolo

-

Development of a Physical-Training Program to Strengthen Soldiers

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Can We Make Our Soldiers Tough Enough? When the Army found that our boys were a bunch of softies, it developed a physical-training program that prepares them in double-quick time for the rough-and-tumble business of war.

-

extracted text

-

WORLD WAR II demands physical stamina far greater than that possessed by the average American boy. Our young men are a sad commentary on the machine age, easy schooling, and easy living. They're softies, compared with their fathers of a generation ago. They look all right; they're taller, heavier, better nourished, and freer from disease. But they haven't exercised as much as their fathers used to, and they're physical weaklings by present-day military standards.

That's the conviction of the three men largely responsible for the U.S. Army's toughening program. These men, now assigned to the Special Service Forces, are Col. Theodore P. Bank, formerly athletic coach at Tulane and Idaho universities; Capt. A. A. Eslinger, director of physical education at Leland Stanford University, and C. H. McCloy, director of physical education at the University of Iowa. Much of the new training system was worked out by this trio just before Pearl Harbor.

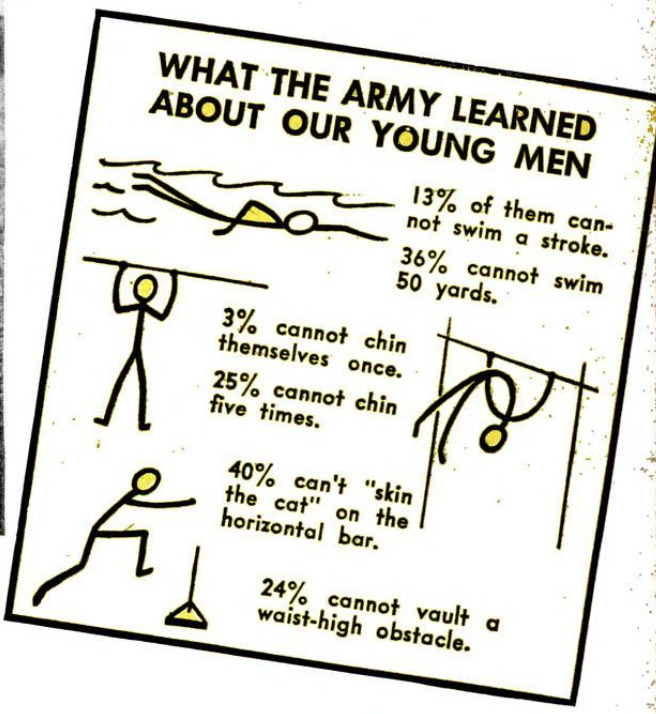

At the school in Washington and Lee University, Lexington, Va., where Special Service officers are trained in the new hardening program, Captain Eslinger gave me some data on the physical unfitness of average American college boys, as of 1940 and 1941.

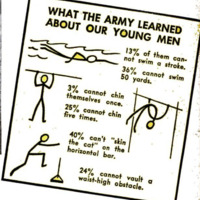

“In a physical-fitness test of 1,000 men at the University of Illinois in 1940,” he said, “the following facts were revealed: 13 percent of them couldn't swim a stroke and 36 percent couldn't swim 50 yards. Over three percent couldn't chin themselves even once, and more than 25 percent couldn't chin themselves five times. About 24 percent couldn't vault an obstacle waist high; more than 40 percent couldn't ‘skin the cat,’ an easy stunt for their fathers.”

Captain Eslinger had examples—taken from battle reports—to illustrate how disastrous it may be to a soldier in wartime to lack strength in his arms and shoulders. “The crew of an American bomber,” he said, “made a forced landing at sea off the Aleutians. A small naval vessel sped to their rescue. With high seas running, ropes were lowered to the airmen floating aboard their collapsible raft. All but one were saved. That man couldn't climb the rope.”

A similar fatality occurred, he said, aboard a U.S. Army transport sunk offshore in operations near Guadalcanal. An enlisted man was caught below decks with no means of escape except through a hatchway only 20 feet above his head. A comrade tossed him a rope. But the man was unable to climb it, and his comrade was unable to pull him up.

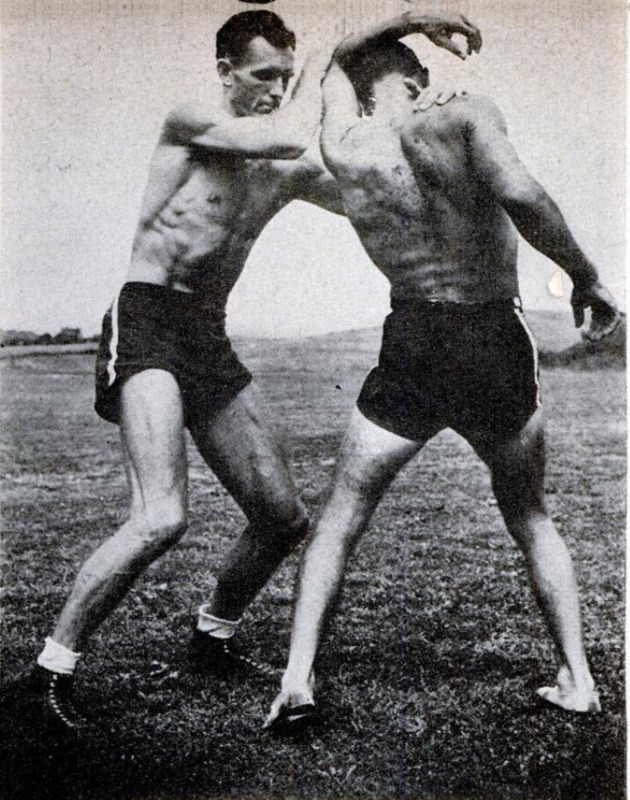

As for strength and agility needed in hand-to-hand combat against such toughened troops as the Nazis, no powers are too great. It was with such situations in mind that the three university athletic directors went over scores of standard drills in calisthenics to develop the single set of 12 that is now working miracles for the Army. They packed into a dozen basic exercises, which can be run through in 20 minutes, more strenuous physical drill than was contained in the 60-minute system used before the war. Then they added “guerrilla” exercises and combative drills, and topped their new system with rough-and-tumble games to build competitive spirit among our troops.

Under the new program, recently compiled in a manual known as Training Circular 87, every soldier in our Army must be tested individually at regular intervals. This determines his muscular strength, agility, endurance, and coordination. It's also a sure way to find out the extent of his improvement under training.

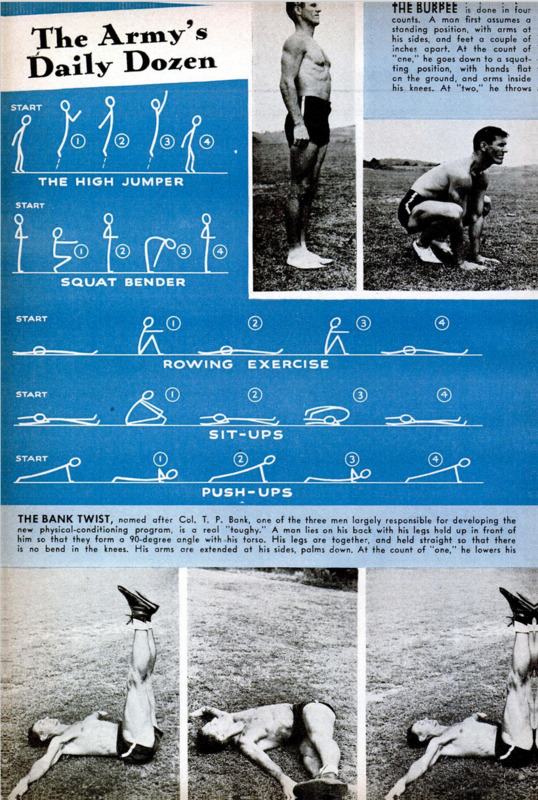

Creators of the program simplified the routines to make every movement an effective training device. They gave each exercise in the now famous dozen a name that soldiers can easily remember; they stipulated an exact number of counts, so that motions can be made in cadence and whole drills run off with a minimum of commands.

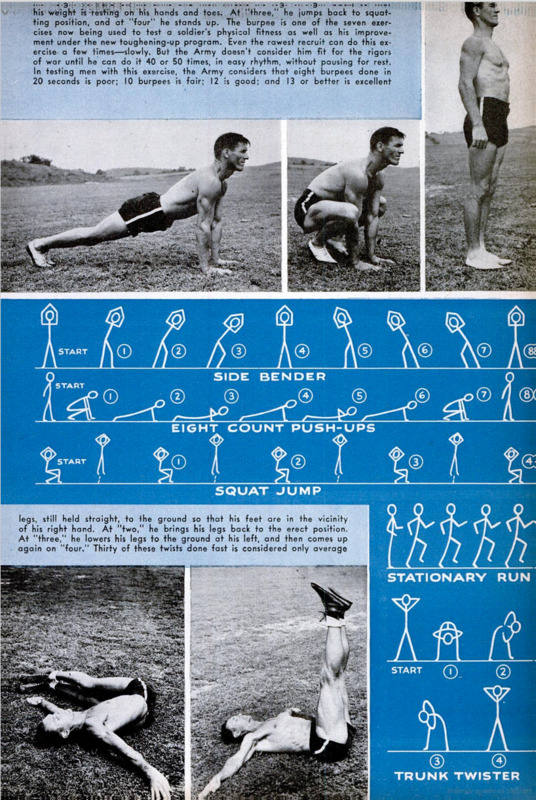

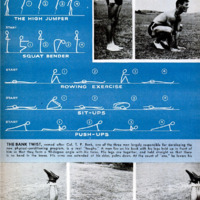

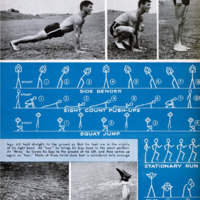

They named their 12 the high jumper, burpee, squat bender, rowing exercise, push-ups, sit-ups, side bender, bank twist, squat jump, trunk twister, stationary run, and eight-count push-ups. Later, they adopted some alternative exercises, known as the mountain climber, the wood-chopper, and the bridge. Most of these names are descriptive of the motions.

In the high jumper, for instance, the men swing their arms from their sides to above their heads and jump straight up, at least a foot into the air. Then they swing their arms forward and jump in that position, then backward and jump. This is done in rapid cadence, from 12 to 25 times before the men pass on to another exercise at a single command, and without any intervening rest.

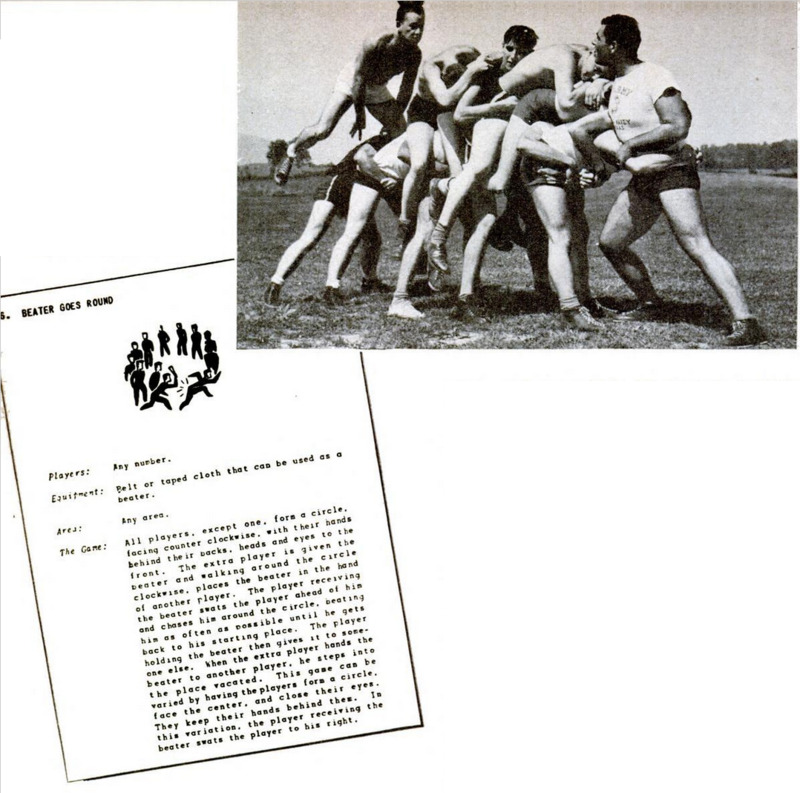

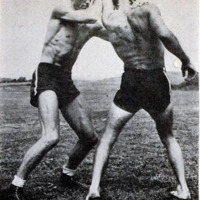

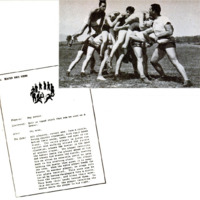

Besides the calisthenics, there are drills in which men of approximately the same weight and height may be pitted against each other, individually or in teams. The very names of these describe what they do. They are the hand wrestle, the pull-hands, the wrist bend (or make-'em-beg), the head push, the shoulder push, the back-to-back push, the knock-em-down, and others.

In the knock-'em-down, for instance, each of two men tries to knock his opponent off his feet in any way possible. Each contestant may tackle, push, pull, lift, or wrestle. The first man who has any part of his body except his feet touching the ground loses.

In developing these exercises, the authors of T.C. 87 did not forget that marching under full field equipment and playing such games as soccer, baseball, pushball, and volleyball are valuable aids to training. They set up some rigorous standards for marching under full pack. Here are some of them:

“March four miles in 45 minutes; march five miles in an hour; march 16 miles in four hours; march 25 miles in eight hours; march and double-time for seven miles without halt.”

Once they were convinced they had worked out an improvement on old Army methods, the physical-education experts made a demonstration test at a camp in California. They took two companies of 250 men each, so equated that each had the same number of men from various sections of the country, from various walks of life, and of various ages. As nearly as possible, these two companies started equal in physical condition. Each underwent a six weeks’ training course, under constant observation; the experimental group with the new system of physical toughening, and the control group with the traditional.

At the start and at the close of this period, every man in both companies received a test in eight exercises. There were pull-ups, push-ups, sit-ups, and three successive standing broad jumps to test their strength. There was the 20-second burpee to test their agility. To test their endurance, each was required to run 75 yards with a man of equal weight on his back, and 300 yards as a sprint. To test their coordination, each was put through a dodging run about obstacles. The improvement of each company was measured on a point system. It showed that the experimental group had gained by 23.5 percent, while the control group, under former Army methods, had improved only 3.5 percent.

The average man in the experimental company increased the number of times he could chin himself from 8.3 to 10.8 times. His push-ups increased from 20.4 to 32.2 times. He cut his time for running 300 yards from 51.2 to 47.5 seconds.

Since that test, the Special Service Forces have been gradually installing their system of physical drill and periodic testing throughout the Army, as officers are trained to conduct it. They have worked out some average physical-capacity standards for soldiers according to seven tests, and a point system whereby every soldier can see where he stands in comparison with his fellows. The job of the athletic officers includes stimulating individual soldiers to improve their ratings.

Three periods of training change the raw recruit into a toughened soldier. The first, of six weeks, emphasizes calisthenics. These gradually give way during the second period—from six to 10 weeks—to competitive games. Thereafter is a period of “maintenance of condition.”

-

Autore secondario

-

Allen Raymond (writer)

-

William W. Morris (photographer)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1944-02

-

pagine

-

57-60, 203

-

Diritti

-

Public Domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by

-

Lorenzo Chinellato

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)