-

Titolo

-

Military gliders, motorless aircrafts with soldiers and supplies transport function

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Title: Silent partner of the plane

-

Subtitle: A new weapon of the present war, motorless aircraft have won a secure place in battle tectics. Here's the story of their development and current use.

-

extracted text

-

TRIED out for the first time in this war,

are military gliders a success? What do

they look like, and how do they work?

And what are the postwar prospects of

gliders in commercial aviation?

When Germany staged the first mass

use of gliders, to invade Crete, and U.S.

and British gliders returned the compli-

ment in taking Sicily, their worth for cer-

tain specialized missions was definitely

proved.

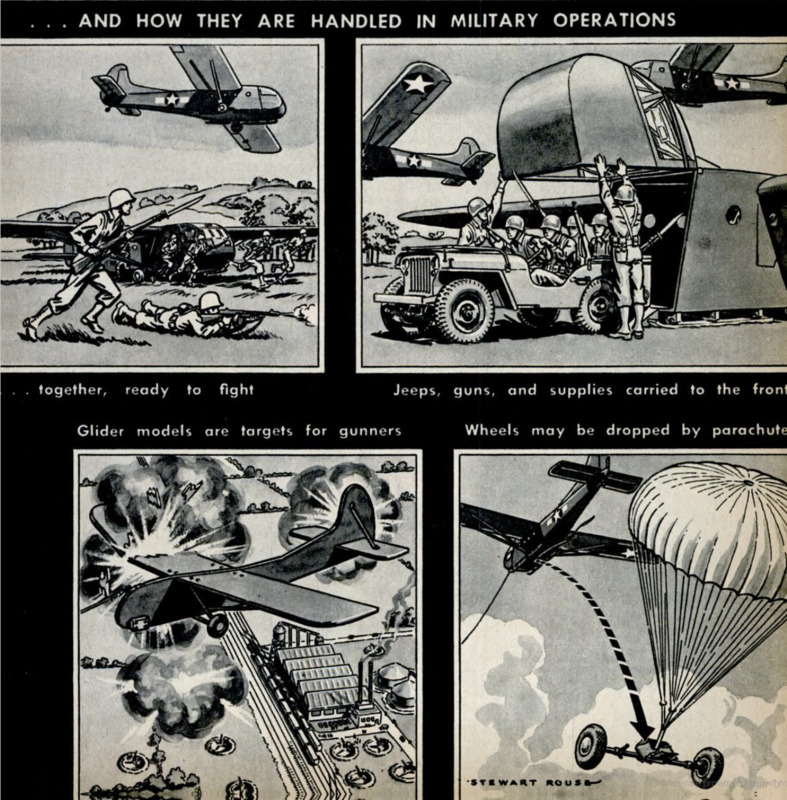

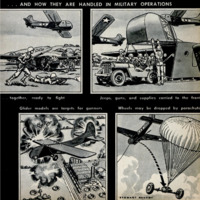

For leading an aerial blitz, glider troops

have an advantage over paratroopers: they

all land together, saving priceless moments

in collecting weapons, getting organized,

and going into action. Quickly and inex-

pensively replaced, compared with powered

troop transports, gliders are expendable.

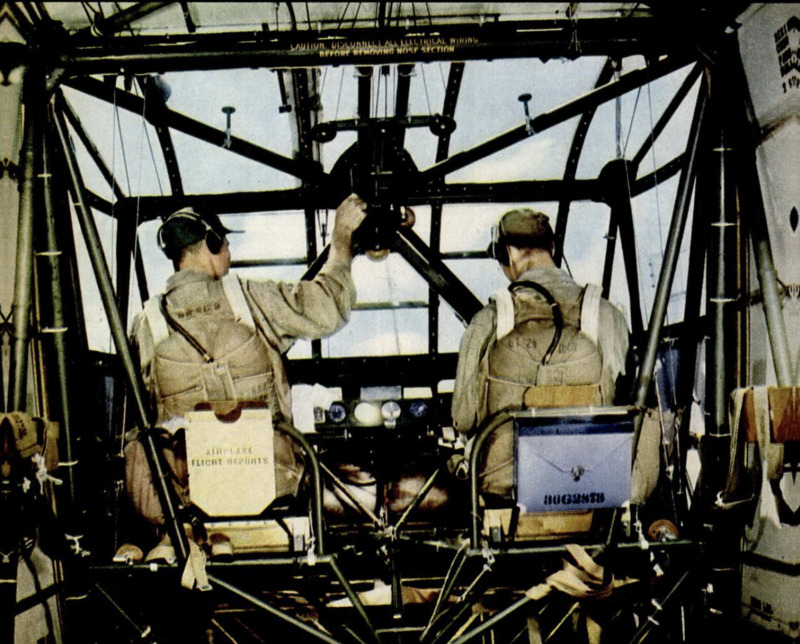

Even if pieces of wings and tail go flying,

it means nothing to slam a troop-carrying

- glider into a high-speed crash landing on

rough ground; a strong cage of structural

tubing protects the crew. Unlike cargo

parachutes that the winds may carry astray,

manned cargo gliders

deliver supplies to ground

troops just where they

are needed.

Military gliders differ

most conspicuously from

prewar sporting sailplanes

in being towed, like flying

trailers, all the way to

their destination. In for-

mer practice, pilots took

advantage of rising warm-

air currents called “ther-

mals” to stay aloft, and

civil aviation authorities

barred airplane tows as

too dangerous. How far

gliding has advanced since

then. was demonstrated

last summer by the first transatlantic

.glider flight, made in tow of an airplane

from Montreal to London.

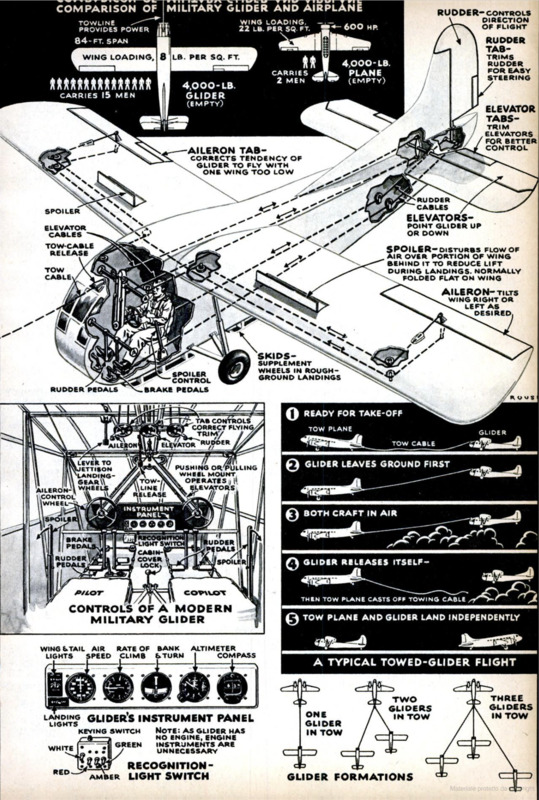

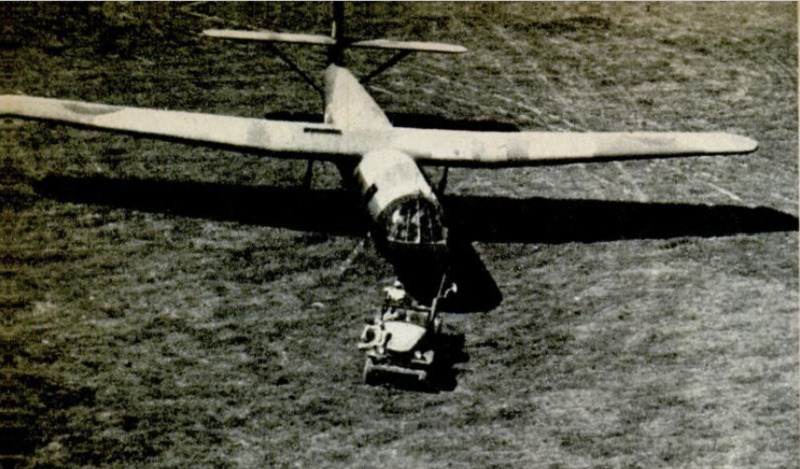

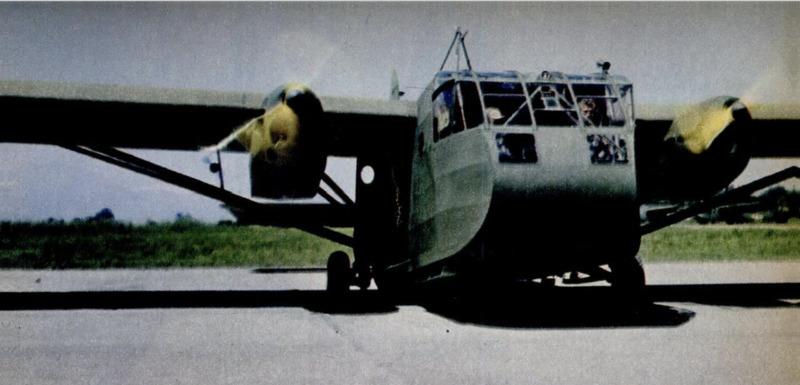

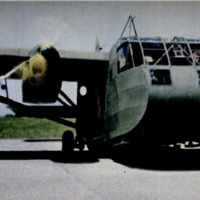

Landing gear for a typical military

glider, which gives it a characteristic squat

appearance on the ground, consists of ski-

like steel runners and a pair of rudimentary

wheels. In some models, the wheels may

be dropped after taking off; they parachute

to earth for recovery and re-use.

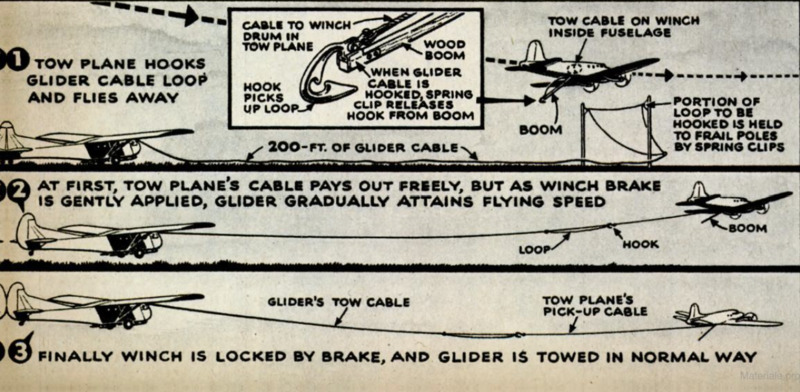

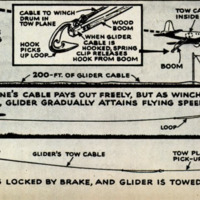

For a normal take-off, both the tow

plane and the glider start down a runway

together, connected by a shock-absorbing

cable of nylon—so elastic that it will

stretch by a third and then slowly contract

to its original length. When more than

one glider is attached, towlines vary in

length to keep wing tips from colliding.

Fanlike formations alone are used, since

| gliders strung one behind another would

be unmaneuverable.

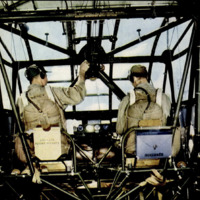

In flight, tow-plane and glider pilots con-

verse by two-way radio. At the destination,

the glider pilot pushes an overhead lever

that unleashes his craft. Instead of buffeting

the wind, he now rides with it, and its gentle

murmur permits

occupants to talk without

raising their voices. 3

To lose altitude rapidly,

the pilot raises a pair of

solid flaps called “spoil-

ers,” which kill the lift

of the wings. A spectac-

ular innovation, illustrated

on this month's cover, has

recently been tested for

checking a glider's for-

ward speed. It consists of

a horizontal parachute,

unfurled from the glider's

tail in midair, and released

or retained as the craft

strikes ground. With such

quick-landing aids, a

tree-skimming approach exploits the ele-

ment of surprise to the fullest.

Gliders of the U. S. Army Air Forces

now range in size from tiny, colorful

training craft, called TG’s, up to the big

green CG-4A, which doubles as a carrier

for troops and for cargo. Pending de-

velopment of still larger and more for-

midable gliders, the CG-4A—currently in

mass production—is the Army’s standard

type. As a troop carrier, it holds 15 men,

including pilot and copilot. Alternatively,

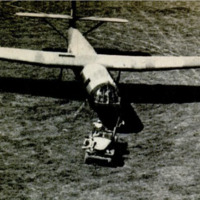

it transports a jeep and six men. Other

cargoes may consist of 37-mm. antitank

guns, 75-mm. pack howitzers, motorcycles,

food, and ammunition. Overall, a CG-4A

measures about 84 feet in wing span, and

48 feet in length. In addition to doors

at its sides, its whole nose may be opened

to discharge men and equipment.

Military experience has demonstrated

limitations as well as advantages of gliders. .

You can’t get something for nothing by

hitching a glider behind a plane. It takes

power to pull it. Trials seem to confirm

the conservative opinion ‘that, for long

hauls, a powered plane alone will transport

a load more efficiently.

Nevertheless, gliders appear destined to

‘play an important role in commercial avi-

ation, closely paralleling their special mili-

tary advantages. Feeder lines, connecting

out-of-the-way communities with through

airways, can employ multiple glider tows to

pick up and let off passengers at any point

along the way. (CONTINUED)

-

Autore secondario

-

Alden P. Armagnac (article writer)

-

Robert F. Smith (photographer)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1944-02

-

pagine

-

94-101

-

Diritti

-

Public Domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by

-

Lorenzo Chinellato

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Immagine 2022-04-10 143345.png

Immagine 2022-04-10 143345.png Immagine 2022-04-10 143218.png

Immagine 2022-04-10 143218.png Immagine 2022-04-10 143238.png

Immagine 2022-04-10 143238.png Immagine 2022-04-10 143303.png

Immagine 2022-04-10 143303.png Immagine 2022-04-10 143149.png

Immagine 2022-04-10 143149.png Immagine 2022-04-10 143359.png

Immagine 2022-04-10 143359.png Immagine 2022-04-10 143453.png

Immagine 2022-04-10 143453.png Immagine 2022-04-10 143523.png

Immagine 2022-04-10 143523.png Immagine 2022-04-10 143542.png

Immagine 2022-04-10 143542.png Immagine 2022-04-10 143559.png

Immagine 2022-04-10 143559.png Immagine 2022-04-10 143617.png

Immagine 2022-04-10 143617.png Immagine 2022-04-10 143632.png

Immagine 2022-04-10 143632.png