-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

A 75mm aircraft cannon mounted on a medium bomber

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Title: Flying big gun

-

Subtitle: America gets the world's most powerful air weapon a cannon of fieldpiece caliber that goes into battle in a combat plane

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

AMERICAN planes now carry the aerial

firepower to back up any plans our

strategists may have for future air offensives!

Firepower, the peg on which air superiori-

ty hangs, has suddenly taken on new mean-

ing for American planes and pilots. The

reason is the achievement of a little group

of Ordnance and Air Corps experts who

have made a World War I dream come

true—the dream of carrying aloft in air-

craft regulation fieldpiece-caliber artillery.

Since the days of the Spad, the Camel,

and the Fokker D7, the armament of mili-

tary aircraft has undergone few really

radical changes. The old .30 caliber machine

gun has but recently given way to the .50

caliber gun developed by American experts

and used by our pilots and air gunners. The

first production air cannon firing an ex-

plosive shell was the 20-mm., only slightly

larger in caliber than a .50 machine gun.

Then came the 37-mm. cannon, around

which the Bell Airacobra was designed.

Some British planes now carry the 40-mm.

cannon, only slightly larger than the Aira-

cobra’s weapon. These guns have proved

highly effective, but our Ordnance men still

dreamed of arming a plane with a weapon

such as the most-used fieldpiece of World

‘War I, the French 75-mm. cannon,

Not until mid-November 1942 did their

plans bear fruit. The setting was far out

in the Pacific, off the California coast. A

plank-and-fabric target bobbed in the surf

directly in the glide path of a North Ameri-

can Mitchell bomber.

Suddenly, while the B-25 was still miles

away, its nose blossomed orange flame.

Gulls wheeling about the floating target

took no notice, for before the sound of the

gun could have reached them, they had

vanished along with the target in a great

upheaval of debris, water, and froth. Amer-

ica had a new aerial weapon—the world’s

deadliest aerial cannon, a flying “75”!

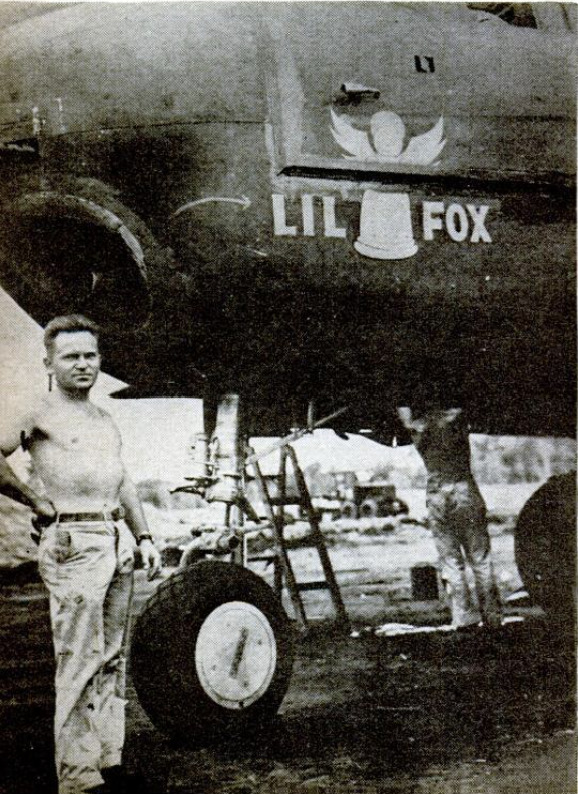

In the cockpit of the Mitchell, lanky Roger |

Rudd, North American test pilot—and, by a |

coincidence, a 75-mm.-gun crew captain in

the World War—relaxed his finger from the

red button on his control wheel. With a grin

he spoke through his throat mike to the

ground: |

“Rapping off over 200 in a mild glide . . . |

good husky jolt . . . scarcely any noise . . .

she doesn’t decelerate a damn bit!” |

That was Rudd’s report on the first pro- |

duction-model test of our new flying artil- |

lery. |

Since this first flight, the flying 75 has ap-

peared in ever-increasing numbers in the

South Pacific and probably in other theaters.

Its pilots came back |

from first missions

with combat reports

that read like pulp

fiction, and with awe

at what the new

weapon had done.

One cannon-carry-

ing plane on its first

mission destroyed a

Nip transport as it

was unloading, and

with one shell ended

the earthly worries

of 15 Japs scurrying

up the beach. On

its second mission it

ploughed five shots

into a large Jap de-

stroyer, hitting the

aft turret, bridge, amidship section, and

bow. Another run on it—now beached—

plastered a stack, the bridge again, and

the deck, and set off internal explosions.

The third mission resulted in the blasting

of runway strips and ground Jap planes,

along with the silencing of reinforced

pillboxes. The cost of all this was 90

rounds of ammunition and a few holes

from flak.

Other planes flying the 75 had similar suc-

cess, and pilots were jubilant over its effec-

tiveness against any type of ground installa-

tion or mechanized equipment. One shell

would completely destroy a light tank or put

the heaviest out of commission. It was equal-

ly deadly against landing barges, ammuni-

tion dumps, locomotives, and power plants.

The 75 has a range roughly the same as

that of the original French 75, with the ad-

vantage of being fired from an elusive plat-

form moving hundreds of miles an hour

through the air. Such a gun, hurling 15

pounds of concentrated destruction from any

angle in surprise attacks, does nothing to

calm the nerves of the enemy, no matter

how battle-tested.

Even in World War I, a few experiments

were made with heavy-caliber ordnance

mounted in aircraft. One of the outstanding

attempts was the Davis gun, a weird weapon

that fired through both ends of the barrel.

From one end came the projectile, while

from the other roared a charge of lead shot.

Sandwiched in between was the powder

charge. This crude arrangement was ex-

pected to overcome the major obstacle in

mounting heavy-caliber artillery in aircraft

—recoil. The Davis gun did overcome recoil

quite effectively, but the back charge of shot

had to be reckoned with when placing the

gun aboard, and the two-way shell was

clumsy to handle. A .30 caliber Lewis ma-

chine gun was mounted atop the contraption

and fired when approaching the target.

Tracers from the Lewis determined when

the cannon was within range of its objective,

for the range of the double-ended charge

‘was roughly the same as that of the machine

gun.

Eventually, the Davis gun was abandoned

as an aircraft weapon, and recoil remained

a stumbling block until American ingenuity

surmounted it many years later.

Shortly before 1939, first tests were made

with an old-style French 75 under the direc-

tion of Captain (now Colonel) Horace A.

Quinn, who was put in charge of the project

as Chief of the Aircraft Armament Develop-

ment Section of the Technical Division,

Ordnance, under

Colonel (now Major General) G. M. Barnes.

‘The gun was mounted in the fuselage of a

junked B-18 bomber and fired on the ground

to test the reaction of the fuselage to the

shock of such an explosion. These early

tests were successful, considering the crude

equipment.

Encouraged but still cautious, the Ord-

nance men next obtained flyable models of

the B-18 through the co-operation of the Air

Forces, and went ahead with the most dan-

gerous part of the experiment—flight-test-

ing and firing the old cannon.

In every case, Captain Quinn himself in-

sisted upon taking the risk of firing the first

rounds from these makeshift mounts, and

to his courage goes much credit for the final

outcome of these dangerous experiments.

Five different mounts for the old 75 were

tested, each more effective and lighter than

the last. These were developed through the

co-operation of the Watervliet and Rock

Island arsenals.

With traditional Ordnance caution, en-

thusiasm was curbed during further modifi-

cation until, in 1940, an improved model was

demonstrated before the Air Corps Board

at Eglin Field, Fla. As a result of this dem-

onstration, and under the direction of Colo-

nel Barnes as Chief of the Ordnance re-

search program, a number of industrial

companies were called in to help with de-

velopment and manufacturing problems.

‘Their wholehearted co-operation produced

a 75-mm. aircraft cannon more powerful

than even the old French 75, with a perfect-

ed recoil mechanism and mount that met

the peculiar requirements of aircraft instal-

lation. To Victor F. Lucht, an Ordnance De-

partment engineer, goes credit for develop-

ment of the recoil mechanism and the work-

ing out of the details that assured flawless

performance of the assembled gun.

After more extensive ground tests, the

new 75 was taken into the air under the su-

pervision of Ordnance personnel. Again

Captain Quinn came forward to take the

risks attending the first firing aloft. The

results justified these risks.

Now the problem was to find a suitable

plane to take this great Ordnance achieve-

ment into combat. As this cannon was a

fixed weapon, the ship to carry it nad to

have speed and maneuverability, with the

guts to stand not only the installation

weight but also the shock of firing. The

size of the installation, too, had to be con-

sidered, along with the necessary equipment

and accessories and a man to load the gun.

Several manufacturers were consulted. It

was a lucky break when North American

Aviation came forward to offer the Mitchell

B-25 bomber as the steed. Already it had

been battle-proved on every front. If it

would do, months would be saved in getting

the gun into combat.

By a happy design coincidence the Mitch-

ell was ideal. Along the left side of the fuse-

lage, under the pilot's compartment, it had

a tunnel used by the bombardier in getting

into his nose position. This might be just

the spot for the placing of the gun.

To North American, then, was given the

exacting problem of installing the 75 in a

combat aircraft for the first time. Com-

pany experts received the drawings of the

gun and installation in mid-August 1942,

and George Bussiere, staff engineer in

charge of ordnance, gathered his able as-

sistants about him and dug in for a session

of sweat and toll.

‘What they really had to work with were

the M-4 aircraft cannon and the M-6 air-

craft-type mount as developed by the U.S.

Army Ordnance Department. What they

had to achieve was the attaching of these

units to the Mitchell medium bomber.

First the group studied the Mitchell's

structure to see if it would do “as is.” It

would—on paper—for months before added

ruggedness had been built in to support the

nose wheel. Tests were made, and the con-

sensus was that she could “take it.”

To accommodate the gun muzzle, a mild-

steel port was fitted to the nose of the ship

at the end of the bombardier’s tunnel. The

nose itself was entirely enclosed in metal,

replacing the transparent sections in the

standard model. Above the cannon muzzle,

mountings for two .50 caliber machine guns

were fitted as auxiliary weapons, and the

necessary armor was added for safety.

During the next four months, test sections

of the altered fuselage were taken under

wraps to isolated sections of the California

coast for testing on a 200-yard range. Here,

in utmost secrecy, test firings were made

with loads ranging from half charges to

more than 115 percent of normal combat

charges. As the thunder of these explosions

died away, the sections were started back

for a final check at the factory, where the

verdict was pronounced with satisfied grins:

“She can take it—and plenty more!”

Just three months from the day when

Bussiere first opened the blueprints, test-

pilot Rudd was firing the 75 over the Pacific.

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1944-02

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

105-108, 222, 228

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public Domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Lorenzo Chinellato

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Popular Science Monthly, v. 144, n. 2, 1944

Popular Science Monthly, v. 144, n. 2, 1944