The dangerous job of recovering the mines that are still in the Atlantic Ocean and in the North Sea

Contenuto

-

Titolo

-

The dangerous job of recovering the mines that are still in the Atlantic Ocean and in the North Sea

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Title: They Are Still at War

-

Subtitle: Two milions deadly foes do not know peace has come

-

extracted text

-

IN the North Atlantic and in the

narrow waters of the North Sea

are hundreds of thousands of the

deadliest foes who do not know that

peace has been declared. They are

the great army of mines, estimated at

two million, planted by the formerly

warring nations. Each one of these

mines carries the power to destroy the

greatest ship. To hunt them down

and rid the seas of them is, perhaps, a

more courage-trying job than any the

fighting men faced during the great

war.

What the Mines Are Loaded With

The cost of these mines in money

was tremendous—something like an

average of $1,000 for each of the two

million. The cost in lives cannot be

reckoned until the last is swept from

the seas. It is a job which, as one of

the world's greatest experts on sub-

‘marine mines told the writer recently,

“can never be prosecuted safely.”

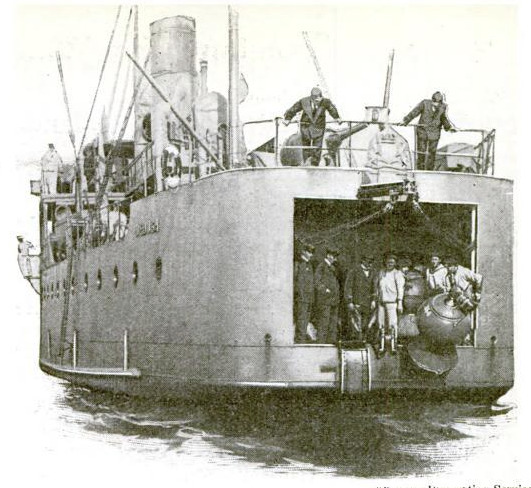

It will be done by minesweepers such

as the one shown in the accompany-

ing photographs. Hundreds of these

‘mine - sweepers, equipped

with the most approved

apparatus for grappling and

raising mines, are manned

by thousands of men to

whom a sudden trip sky-

ward would be all in the day's

work.

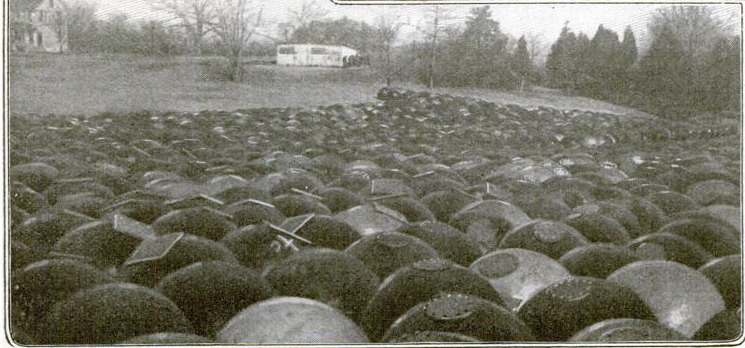

T.N.T., an average of 200 pounds

of it to each one, is what the mines

are mostly loaded with, which means

that there is a total of about 25,000

tons of this terrific explosive to be

harvested. And harvested it will be;

for this undertaking is not a matter of

destroying the mines, but of salvaging

as many of them as possible. The ex-

plosives planted to kill are also useful

in the peace-time arts that help men

live; and then—well, the nations have

not disarmed yet.

Some of the mines will be cured of

their bite by time—those that depend

upon fulminate of mercury or similar

detonating compounds to set them off

when a ship strikes them deteriorating

quite rapidly and becoming unreliable

as death-dealers in about six months.

But there are great numbers of later

types so improved as to keep alive

no one knows just how long.

As long ago as the Russo-Japanese

war, when submarine mines

had not beenso perfected as to

give them the long life of those

afloat today, for a long time

after hostilities had stopped,

ships were sunk by mines

drifting about the Pacific.

Fortunately, the trend of the

currents in the North Sea,

where the vast mine-fields

were placed, is such that the

danger of large numbers of

mines getting into the main

steamship lanes is mot so

great as it would be other-

wise. Nevertheless, the dan-

ger is very real.

How They Are Raised

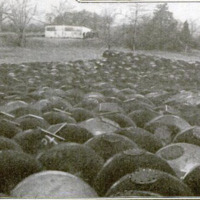

The photographs show two phases

of the work—raising the mines and

stowing them. Having grappled a

mine, the sweeper's crew hoists it

on board through the huge open port

in the stern. Then, along overhead

trolley tracks and flanged deck

tracks, the mines are moved to

their appointed places, with never

a jar.

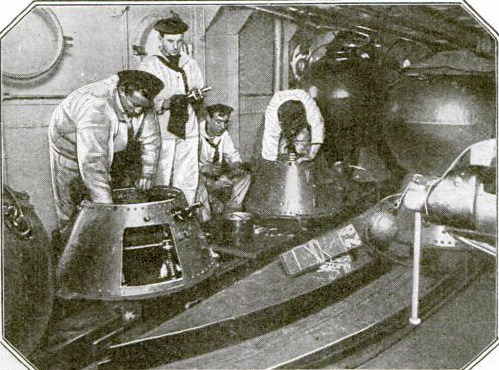

The interior view shows the sailors

at work on mine anchors which con-

tain the automatically operated cable

windlasses that hold the mines at just

the right distance beneath the sur-

face to be most deadly. The mines

themselves can be seen hanging

from the overhead trolley.

-

Autore secondario

-

Press Illustrating Service (Image copyright)

-

Keystone View Co. (Image copyright)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1919-06

-

pagine

-

71

-

Diritti

-

Public domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by

-

Davide Donà

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)