-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

The colloidal fuel used to power warships during World War I

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Making a New Fuel to Order. How colloidal fuel helps oil and coal to do more work

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

THE mightiest war-ships burn

under their boilers not coal but

oil. In 1917 and 1918 it was so diffi-

cult to obtain oil that for a time it

seemed as if the battleship fleets of

England, France, and Italy would be

unable to perform their task of bottling

up Germany and Austria. The situa:

tion was alarming. The submarine

was literally turning off the spigot of

Europe's oil supply.

In this emergency the engineering

committee of the Submarine Defense

Association of New York, of which

committee Mr. Lindon W. Bates is

chairman, determined to begin a series

of investigations to meet naval de-

mands. An oil expert of inter-

national renown, he decided

that a composite of oil and

finely powdered coal would meet

the demand.

It was not a new idea; but

it had come to naught because

the heavy coal particles always

settled in the oil. Some way

had to be found of holding the

‘minute coal particles in suspen-

sion for a number of months.

When the problem was solved

“colloidal fuel” was created.

Particles that Always Dance

What is a colloid? Chemical

history answers. Between 1861

and 1864 Thomas Graham dis-

covered that, when certain dis-

solved substances are separated

from a surrounding solvent

by a membrane of parchment

or fish-bladder, some of them pass

through the membrane freely into the

surrounding solvent, while others re-

main behind, only to diffuse very

slowly. The particles that do not

pass through are evidently larger than

the pores of the membrane. Graham

called them “colloids.”

Victor Henri, a French scientist who

has done much to explain colloids,

says: “There are no colloids; there

is only a colloidal state, just as there

is a solid state and a liquid state.”

When you blow a puff of cigarette

smoke from your mouth you see a

gaseous colloid of carbon. The finest

ruby-glass is a solid colloid of gold.

In a colloid there is no chemical union

or combination between the particles

held and the medium that holds

them. A current of electricity passed

through a colloid drags the particles

with it.

These particles are always in a state

of violent agitation, dancing about

irregularly because of the collisions

that incessantly take place.

Preventing the Powder from Settling

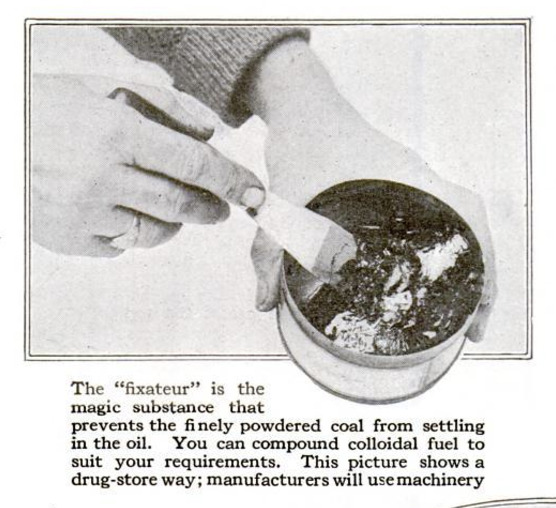

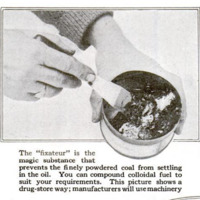

Colloidal fuel is simply a mixture of

very finely powdered coal, oil, and a

stabilizer (“fixateur,” Mr. Bates calls

it) to prevent the coal particles from

settling in the oil.

The nature of the fixateur is not

disclosed. It

produces a

state in which

the force of

gravity is so

far overcome

that the mix-

ture of coal

and oil remain

permanent for

months. When

settling does

eventually

manifest it-

self, brief stir-

ring is all that

is required to

restore the

fuel to its

previous con-

sistency.

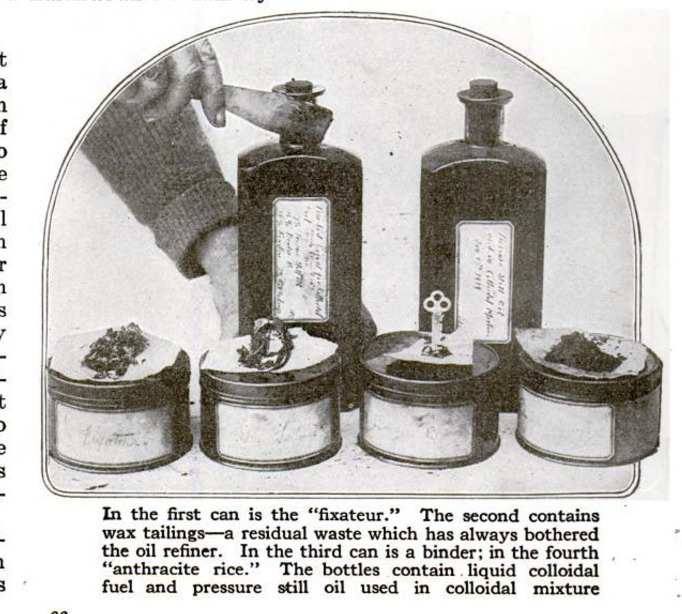

It is possi-

ble to sustain

for months

from thirty to forty per cent of coal |

in oil. Ina colloidal fuel about forty-

five per cent oil, twenty per cent tar,

and thirty-five per cent pulverized

coal can be combined, thus displacing |

more than half of the oil and securing

equal or greater heat values for each

barrel, thereby saving much money.

At least twenty-five per cent of the

fuel oil now burned is conserved and

the world's supply of liquid fuel is

increased by fifty per cent.

Oil refiners have always won-

dered how they could dispose of

their residues profitably. Col-

loidal fuel supplies the answer.

The “Cinderella products of re-

fining,” as Mr. Bates calls them,

can be used to prepare a fuel

that will command a premium

because it is valuable in making

the higher grade alloy steels.

It Can Be Pumped Like Oil

Colloidal fuel gan be com-

pounded like a prescription.

This means that the particular

kind of fuel best suited for a

particular plant can be made by

a central laboratory. One com-

posite in the range of ordinary

temperatures is composed of

about half coal and half oil. Another

unctuous semi-liquid is nearly three

fourths coal and one fourth oil. The

more coal that is added the more

paste-like the fuel becomes. But all

the pastes are mobile up to sixty per

cent coal, and are pumped and atom-

ized as if they were liquid. With the

liquid grades the oil-burning equip-

ment of a vessel or a plant need not

be changed.

At sea astonishing results

have been secured. The

net saving of oil on the |

research vessel with which |

the Submarine Defense |

Association experimented

amounted to twenty-seven

per cent. Moreover, with |

the same tank or bunker

space a longer cruising

radius without refueling is

obtained. A war-ship ora

merchant-ship can increase

its steaming radius up to

twenty-five per cent.

Cost Savings

The savings of cost in- |

volved in the use of col-

loidal fuel are remarkable.

An industrial company in

Ohio burns three hundred

‘bushels of oil per day; its oil

costs seven cents a gallon;

its coal five dollars a ton.

A saving of fifty-five cents a barrel,

or one hundred and sixty-five dol-

lars a day, is effected by the use of

colloidal fuel, quite apart from con-

sidering the conservation of oil and the

reduction of transport.

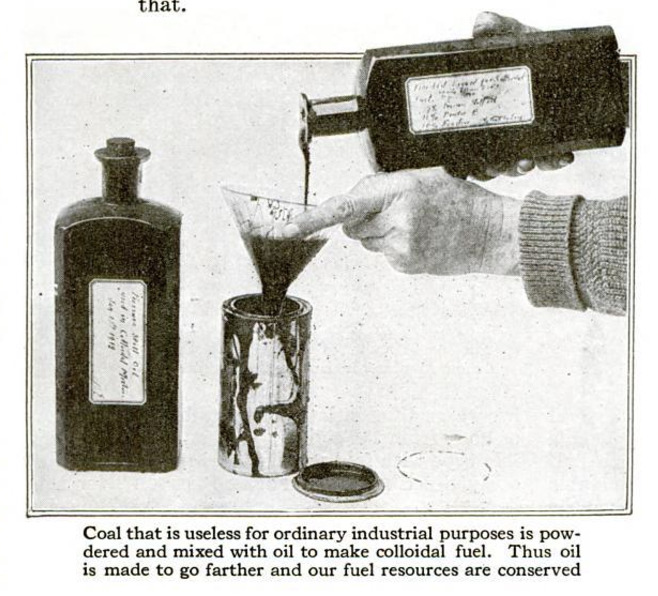

Oil is now extensively used in

furnaces of various kinds—brick-kilns,

annealing plants, blacksmith shops,

brass foundries, and steel works.

About seventy per cent of the oil

burned by these furnaces can be made

to do the present duty of one hun-

dred per cent, and more cheaply at

that.

A certain steel plant uses three

thousand barrels of oil daily, and soon

it will require four thousand five hun-

dred barrels. But the three thousand

barrels of oil with coal incorporated

and used as colloidal fuel will be

ample for the full output, thus effect-

ing a saving of about five hundred

thousand barrels a year.

In industrial plants many millions

of barrels of oil ere consumed annu-

ally. If only twenty-five per cent of

this oil were displaced by fluidized

coal great savings would result. Three

million barrels of oil em-

ployed in colloidal fuel

could do the work of over

four million straight barrels.

The oil reservoirs of the

world are being drained to

their very dregs. We must

conserve oil, but not at the

expense of industry.

Using Low-Grade Coal

Colloidal fuel opens the

doors wide to let the world

have from the stills all the

assistance it needs without

starving hungry boilers or

flaming furnaces of the

grosser fluid fuels which

constitute their food.

Moreover, great deposits

of low-grade coal, as well

as large quantities of

lignites, brown coals, and

waste dusts, are added to

the world’s fuel supplies.

The world is familiar with

three kinds of fuel—solid (coal), liquid

(oil); and gas. We now have a fourth |

fuel which promises to become of

world-wide importance. |

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Walter Bannard (writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1919-07

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

66-67

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Davide Donà

-

Alberto Bordignon (Supervisor)

Popular Science Monthly, v. 95, n. 1, 1919

Popular Science Monthly, v. 95, n. 1, 1919