-

Titolo

-

Fighting Fire from the Sky. The forest ranger becomes an aviator

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Fighting Fire from the Sky. The forest ranger becomes an aviator

-

extracted text

-

VISITORS to our national parks

this summer have been consider-

ably puzzled by the frequency

with which airplanes and_dirigibles

have skimmed overhead. No reason

for this activity was apparent, now

that the war is over.

However, an excellent reason has

existed: the flyers were acting as aerial

patrols, watching for and reporting any

forest fires they discovered. Thus

Uncle Sam has found an important use

for his aces of the air right here at

home.

Heretofore the work of patrolling

United States forests to locate and

hght fires has

been entrust-

ed to men

on horses,

motoreyeles,

or railroad

speeders,

and partly to

watchers stationed at lookout

points. The former travel about from

place to place, while the watchers,

who are located at advantageous

|

pots, usually on the top of some high

mountain-peak, never leave ther post,

but romain constantly on the lookout |

for fre.

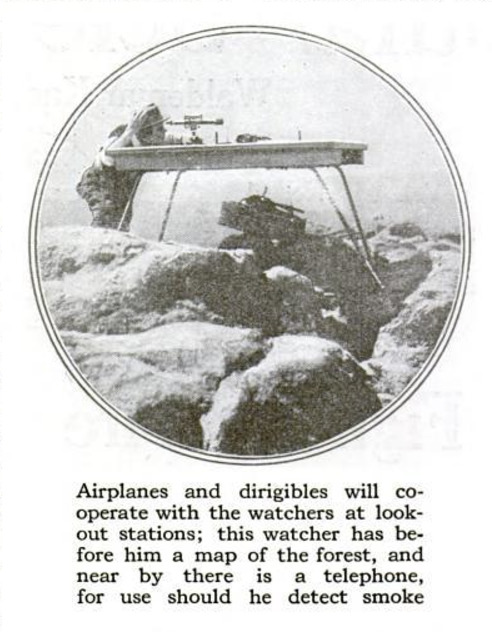

“The observers at lookout stations

aro provided with all the latest scion.

tlic instruments for locating distant

objects, and vith carefully prepared

naps showing the nameso all canyons, |

streams, roads, Tanger stations, and

tho ike:

How the Watchers Do Their Work

“These men hive powerful field-glasses,

and a telephone leads to the nearest

Tanger station and to tho foreat super.

Vitors ofc. If a firo n discovered, |

the watcher immediately telephones

to headquarters, giving the location of |

the fire as it is projected on the map

of the station; u crew of men in des

patched to fight it.

“The offciency of this system has |

been increased from year to. year,

until now it In ar up-to-date and ut |

successful, in its own fold, 43 that of

municipal fire department, In fact,

tho same cusentil factors for success

are employed in the forest work that

are universally recognized aa neces.

ary for fighting fires in cities: namely,

first, datoction of the blaze before it

hin gained headway; and, second,

prompt attention.

According to reports compiled by

tho Forest. Service, there wero in the

United States an’ sverage of 28,735

fires a year. between. 1015 and 1917.

The ground covered by these fires

amounted to 8,052,945 acres. Tho esti

mated damage was 39,875,000.

A roport. covering the’ period be |

tween 1913 and 1917 showed a yearly |

average of 6,184 forest fires, with

56,663 acres burned and damage to

the extent of $300,000.

Last fal it occurred to oficial of |

the Forestry Bureau to supplement the.

ork of the regular forest rangers by

the addition of air scouts, and a fo

experimental flights were made to de-

termina the value of the airplane and.

dirigible in this connection. These

experiments proved so satisfactory

that Secretary Baker issued an order

directing the Air Service to cooperate

with the Forest Service in the work of

forest fire patrol,

and, beginning

with the first of

June, the plan was

regularly put into

operation.

Air scouts and

bombers who saw

service in the

Great War were

set to work in

the forests; and

dirigibles — filled

with the new

non - inflammable

helium gas in-

stead of dangerous

hydrogen—will

also be used in

patrolling the

forests for fire.

Reports receiv-

ed by the Forestry

‘Bureau show that

the airmen experience no difficulty in

detecting fires in heavy timber at an

elevation of ten thousand feet and

even more. From this.it will at once

be evident what an advantage the air

scout enjoys over the watcher in a

lookout station. Even when these

stations are located on mountain-tops,

the range of the observer is more or

less limited by reason of the character

of the country cut by deep canyons

and broken by mountain-ridges. Fur-

thermore, the area of country that he

can see at any time is always the same,

whereas the airplane scout, flying

swiftly at a much higher altitude, is

enabled to cover a wide and ever-

changing stretch of country within the

space of a few minutes.

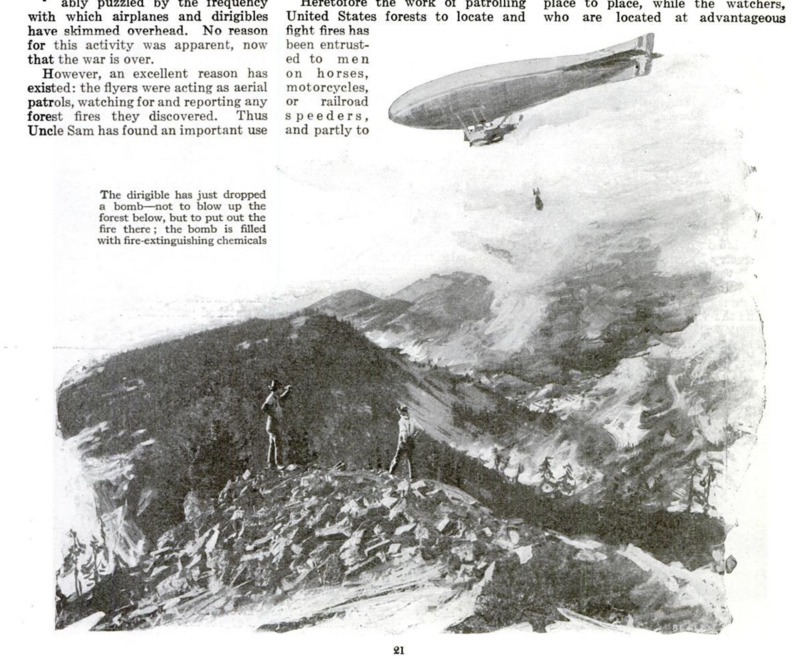

The aerial observer has still another

advantage, of the greatest importance,

over the watcher in the lookout station.

The latter, when he has discovered a

fire, can do nothing more than tele-

phone its location to the nearest fire

guard; he depends upon others to go

to the scene and combat it. On the

other hand, the air scout, when he has

located a blaze, can send in the alarm,

and then, swoop-

ing down over the

spot, drop on it

bombs charged

with suitable

chemicals for ex-

tinguishing fires.

By this means he

is frequently en-

abled to put out

the fire unaided,

or to check its

growth until the

regular fire-fight-

ers have time to

reach the place

before it has gain-

ed any consider-

able headway. In

this connection, a

plan that is soon

to be tried out

proposes trans-

porting fire-fight-

ers in dirigibles from which ladders

can be lowered to the ground.

Warnings Flashed by Wireless

The observer in a lookout station

locates fires by means of triangulation,

reports being telephoned from separate

observation points. The air scout

locates them by coordinates in the

same way that gun-fire is directed to

a particular spot or object—that is,

by means of squares drawn on dupli-

cate maps, one being in the possession

of each airplane observer and another

in the office of the forest supervisor.

The tentative plan is to equip the

patrolling airplanes with wireless sets,

with which the pilots may flash the

first signals of fire. Roads and path-

ways where a carelessly thrown cigar-

ette may be the cause of thousands of

dollars’ worth of damage will, of course,

be watched particularly.

-

Autore secondario

-

Robert H. Moulton (writer)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1919-10

-

pagine

-

21-22

-

Diritti

-

Public domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by

-

Davide Donà

-

Alberto Bordignon (Supervisor)