-

Titolo

-

How airplanes were used during World War I and their possibles improvements and uses in peacetime

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

What of Tomorrow's Flying? Is the airplane safe? Can you fly where and when you like? What's the cost?

-

extracted text

-

WHEN the manufacturers of

airplanes turn to the public for

support, they are met with

conservative skeptical questions: “Is

flying safe? What about these acci-

dents?” The manufacturers reply

with statistics to prove that flying is

no more dangerous than automobiling,

that the blacksmiths and carpenters

who built the first flimsy machines

have been supplanted by engineers

who test the wood, steel, and wing

fabric used in construction, and that all

the resources of modern science are

tapped to build an airplane that is

safe,

When bombs were dzopped on Paris,

London, Mannheim, Freiburg, and

Constantinople, and whole flocks of

raiding airplanes performed thelr grue-

some death-dealing mission with clock-

like precision, who can doubt any

longer? As for safety, diplomats and

generals, whose lives no nation could

afford to risk, were transported with

ease and despatch through the air.

The world has literally been bombed

into conviction. “The war has en-

larged our mental horizon,” as one

British technical periodical put it.

Peace-Time and War-Time Flying

The men who guided the bombing

and fighting planes over the battle-

front were in a far more precarious

position than any peace-time flyer will

be. They were literally flung into the

air and ordered to perform what was

expected of them. There were no

prepared landing grounds. And yet,

despite this handicap, war-time flying

‘was safer than most of us suppose.

Major-General George O. Squier,

in a paper read before the American

Institute of Electrical Engineers,

stated that of all the flying casualties

only two per cent were due to anti-

aircraft fire from the ground or from

enemy machines in the air and eight

per cent to faulty construction. And

the other ninety? Traceable directly,

he assures us, to negligence, in-

competence, or ignorance on the part

of the fiyers. If pilots are properly

trained how much safer will peace-

time flying become!

Moreover, the campaign in the air

over the Italian front must have con-

vinced any skeptic of the airplane's

safety. Among the mountain ranges

where Italian and Austrian aviators

fought there was nothing that remotely

resembled a smooth, safe landing

green. And yet, neither Italians nor

Austrians hesitated to fight or to fly

over each other's territory on bombing

expeditions.

The last piece of convincing evidence

was presented when the fighting pilots

literally flew to the other extreme; in

other words, when they supported the

charging infantry by skimming over

the ground and pouring a hail of

machine-gun bullets on the enemy in

his trenches. What if engines had

failed then? There would have been

only a shell-torn No-Man's-Land on

which to alight. Yet we have still to

learn of any wholesale calamities that

befell these low-flying machines.

And then, the night flyers —what

shall be said of them? They knew

only the direction in which they were

to fly in order to bomb an ammunition

dump or a munitions factory—nothing

of the ground in the terrible darkness

below. If perilous missions such as

these can be carried out in safety, who

shall say that when all the earth is at

peace, when cities are ready to de-

spatch and receive the winged messen-

gers of the air, flying can never take

its place in our mercantile life?

The truth is that the airplane today

is in much the position of the steam-

ship and the locomotive a century ago.

Prejudice alone must be overcome.

Elaborate and complicated wharves

had to be created before the steamship

could become of mercantile impor-

tance. Rails had to be laid, stations

built, round-houses and repair-shops

erected, before the steam locomotive

could play its part in the transporta-

tion of passengers and freight. Simi-

larly, a great organization must be

developed before the flying-machine

shall be able to realize the dream of

those who would span the Atlantic in

a day or wing their way in a few hours

from New York to Chicago.

Needs of the Airplane

The flying-machine traverses the

pellucid air unhampered by hills or

poor roads. But that is not enough.

Before commercial passenger-carrying

airplanes appear in large numbers,

before airplane touring shall become as

common as motoring, the face of the

earth must be prepared. Although

the fiying-machine is a thing of the air,

it must start from the ground and it

must alight on the ground.

Here and there are a few army

aviation fields. More, much more,

must be done. Every civilized coun:

try must survey itself with a critical

eye and note what localities are best

suited to serve for landing and alight-

ing. Between New York and Chicago,

for example, prepared aviation fields

should be found at intervals of not less

than one hundred miles.

Now, to dot a whole country with

hundreds, even thousands, of aviation

fields is a task of such magnitude that

only a government can accomplish it.

Mindful of this, the United States

Army has already addressed itself to

the task. Chambers of Commerce all

over the country have been asked to

study the country around their com-

munities and to indicate those local

ities that seem best fitted for land-

ing fields. The Government knows

exactly what it wants. It has sent

Chambers of Commerce plans of

aviation fields and of the sheds and

repair-shops to be built.

The preparation of the ground

will make the flying-machine abso-

lutely safe. Automobile engines

now stall in the middle of the road.

Flying-machine engines also stall |

in the air. The passengers of a

touring car have only to step out

on solid ground and walk if the

engine should fail them; but, in a

similar predicament, the man in

the air must glide down to the

ground.

The Higher You Are, the Safer

Paradoxically enough, the higher

you are in a flying-machine the

Safer you are. When an engine

balks at a height of a mile or so,

you cast your eye about for a

smooth piece of turf. You may

glide from three to five miles by

skilful handling of your craft. Is

it not obvious that with Govern-

ment_airdromes everywhere you

will be sure to find an alighting

place? :

The flatter the angle at which a

fiyer alights, the safer for him.

Hence the field must be open from

all sides. 11 it is fringed by trees

and buildings the flyer must

plunge down too steeply for safety;

it will be difficult for him to

flatten out at the right moment.

The difficulty of landing at high

speed has probably been greatly

exaggerated. We have only to

consider that fighting flyers in

their high-powered machines

landed safely at sixty miles an

hour. If the ground can be ap-

proached at a very flat angle the

pilot has less to fear from impact

with the solid earth at high speed

than from the momentum that

must be expected in taxiing over

the ground.

‘The flying-machine needs brakes

of some kind. Why not apply the

usual band-brakes to the wheels?

Because a machine that is held

back below its center of gravity

will somersault at high speed.

Perhaps the solution is to be found

in some method of forcing the tail

down with tremendous leverage while

the brake is applied. A horizontally

mounted propeller at the end of the

tail might answer the purpose—a pro-

peller which, during flight, may be

held parallel to the fuselage, so that

the head resistance is not increased.

It is even conceivable that the self-

starter of the engine may be used to

drive the horizontal propeller during

the short period when its services will

be required.

It may be urged that this problem of

holding the tail down while the brakes

are applied is not easily solved. It

entails, for instance, the use of a

device to prevent an increase in the

angle of incidence of the wings, so

that the machine may not rise from

the ground in the effort to check it.

When landing and launching grounds

are to be found everywhere, it will be

possible to design the small inexpensive

airplane—the machine that can be

kept in a kind of garage and trundled

out as readily as if it were the cheapest

of Detroit automobiles. Capacious

fuel-tanks will be unnecessary. It

will be possible to refill the tank every

hundred miles, if need be. Because

no extraordinary feats will be de-

manded of it, the engine need not be

of the enormous power demanded by

the fighting flyer.

Government Aviation Maps

Maps, too, must be issued by the

Government—maps to indicate the

best route between two given points.

‘This means the careful exploration of

the entire country from the air pilot's

point of view. Enormous as the task

may seem, it is far more easily ac-

complished than may be suspected.

The army dirigibles have only to be

pressed into service—craft that may

fly as low as they please and photo-

graph at leisure the territory below.

Miracles in photographic map-mak-

ing were performed during the war.

Similar miracles must be performed to

chart the country for the pilot of the

future. His map must indicate the

meteorological characteristics of the

region over which he flies—must tell

him the direction in which the pre-

vailing winds blow, what invisible

atmospheric perils are to be avoided,

how high to fly over a given region,

and the hundred and one facts that he

must know in order to reach his

destination quickly and safely.

We talk a good deal about the

weather nowadays; we will talk far

more about it when a whole people

takes to the air. The Weather Bureau

must prepare to extend its activities.

Its local reports and maps must be

even more practical than they are

now; they must tell a man exactly

how he must fly to any given point

within a radius of one hundred miles.

At present the Weather Bureau con-

cerns itself but little with the influence

of the ground; but it is precisely the

influence of the ground that makes |

flying favorable or unfavorable in a |

given region. An invisible surf of air |

is dashed up against every mountain. |

A lake, a grove, a collection of build- |

ings, in a word, every protuberance, |

has its effect in foreing air-currents in |

this direction or that. And all these in- |

visible disturbances the Weather Bu- |

reau must visualize for the airman.

Fog will be the only peril to be

feared. But even fog will lose much

of its terror when the Government has

carried out its plan of establishing

radio beacons all over the country, to |

extend its airplane mail service.

Radio Beacons Will Help

What is a radio beacon? Simply a

station from which wireless waves are

sent in all directions, to be picked up

by the flyer lost in a fog or groping his |

way through the night. Part of its

radio equipment is the direction-finder

—a mere loop of wire that can be

swung in any direction on a vertical

axis. When the loop is turned in the

direction of the oncoming waves the

beacons’ signals are received most

clearly; when it is turned at right

angles nothing is received. “I am

Louisville,” “I am Toledo,” “I am

Easton,” beacon after beagon will

literally shout at regular mtervals-with

the aid of automatic sending devices.

And hundreds of pilots in the air will

hear and guide their machines un-

erringly toward the particular beacon

that is their destination.

The commercial - companies will

surely equip their large passenger-

carrying planes with such radio con-

veniences. But what of the business

man or the tourist who flies alone in a

machine unprovided with such aids?

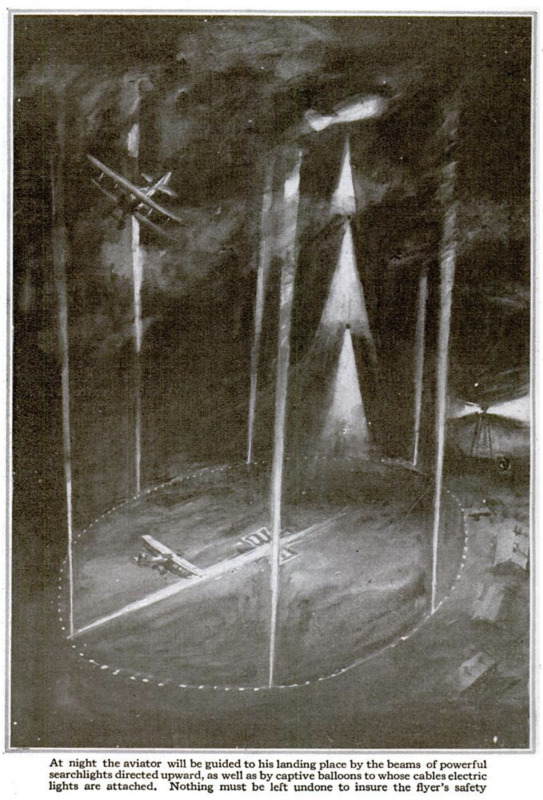

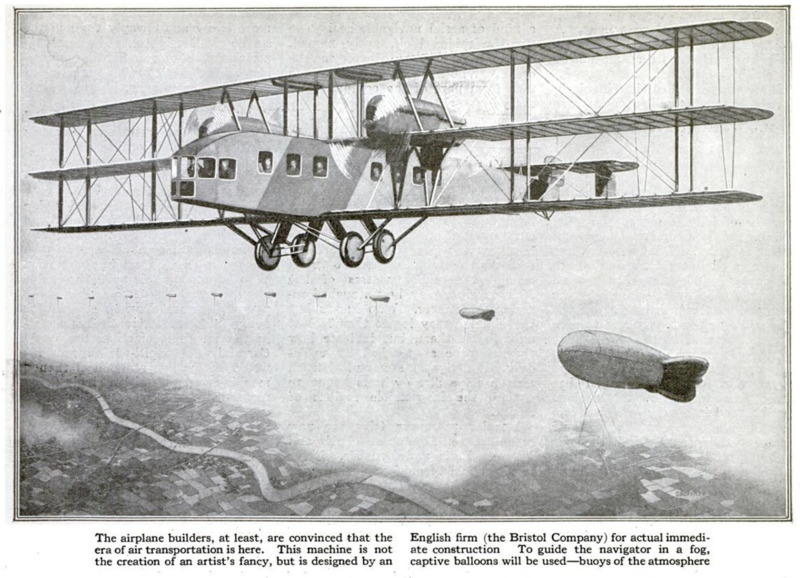

Balloons will guide him—great captive

balloons floating high above the fog

and illuminated at night. Every land-

ing field will thus literally rear its

head above the clouds. The flyer

sees the light and heads for it. He has

but to spiral down around the cable

that holds the balloon captive to reach

the ground below in safety. Ground

lights will make his landing safe.

In his “Night Mail” Rudyard

Kipling suggested a plan that may

also be realized in order to make flying

safe at night. He drew a picture of

searchlights throwing their gleams

vertically into the sky—impalpable,

luminous sign-posts that point the

way when the night is clear. What a

wonderful spectacle will be presented

to the man in the air as he flies from

Now York to St. Louis through the

night! His lane will be as plainly

marked-out for him as are his electric-

ally illuminated streets at-home. For

miles and miles he sees the long, stiff

pencils of light thrust upward from the

ground or great captive balloons each

bearing a powerful electric light. A |

country road at night would be danger-

ous in comparison with an air-lane so |

‘painstakingly marked.

The flying-machine is singularly

plastic, As we know it today, it was |

molded to meet the exigencies of war;

as we shall know it in the future, it will

be molded to meet the demands of

commerce. It is adaptable. "The man.

who fought at a height of twenty thou-

sand feet placed his reliance on an |

engine of enormous power, and on |

wings especially designed for fast

climbing. The commercial pilot will

be less exacting. What need is there |

for him to climb ten thousand feet in

six minutes? What need has he of an

extraordinarily high ceiling? He |

wants engine trustworthiness, and the

builder of engines is prepared to give |

it to him by making the power-plant

heavier and more durable than the |

army flyer demands.

The war, curiously enough, has

served to show us how the airplane |

may be used in a very practical way

for scientific purposes. To fly over |

the enemy's lines and make thousands

of photographs of positions is the exact

equivalent of mapping a jungle or a

wilderness which may be penetrated |

only at the risk of life and the suffering

of untold hardship. In a single day

the Coast and Geodetic Survey could |

thus perform more useful work than it

now accomplishes in months when it |

surveys remote islands in the Pacific or

the wilds of Alaska. |

Fire-Extinguishing Bombs

Already the Forest Service is plan-

ning to use the airplane to detect

forest fires and to extinguish them by

dropping upon them bombs contain-

ing fire-extinguishing chemicals. The

Coast Guard will find its task of

locating and blowing up derelicts at

sea reduced to a matter of hours

when it enlists the seaplane into its

service.

During the war the British dropped

food into towns beleaguered by the

Turks. Why may not bomb-carriers

supply colonies devoid of roads or rail-

ways with the material that they need?

The Sahara Desert, now painfully and

tediously traveled by camels, becomes

a kind of aerial navigable sea. The

German raider Wolf, aptly named,

used a seaplane to locate its prey on the

ocean. Who knows but the seaplane

may form part of the equipment of

every first-class steamer?

Exploring by Airplane

With what ease will the airplane

transport the explorer over mountain

ranges, swamps, jungles, and deserts!

The camera will enable the explorer to

bring back a far clearer, far more ac-

curate record of the country that he

has traversed than if he had explored

it on foot. In the uncharted districts

around the upper waters of the

Amazon river may be untouched re-

sources of rubber. Who knows but

the airplane may locate them? Not

only locate them, but indicate how

they may be approached by undis-

covered navigable streams? British

airmen have already thus begun to

explore the inaccessible regions of

Africa.

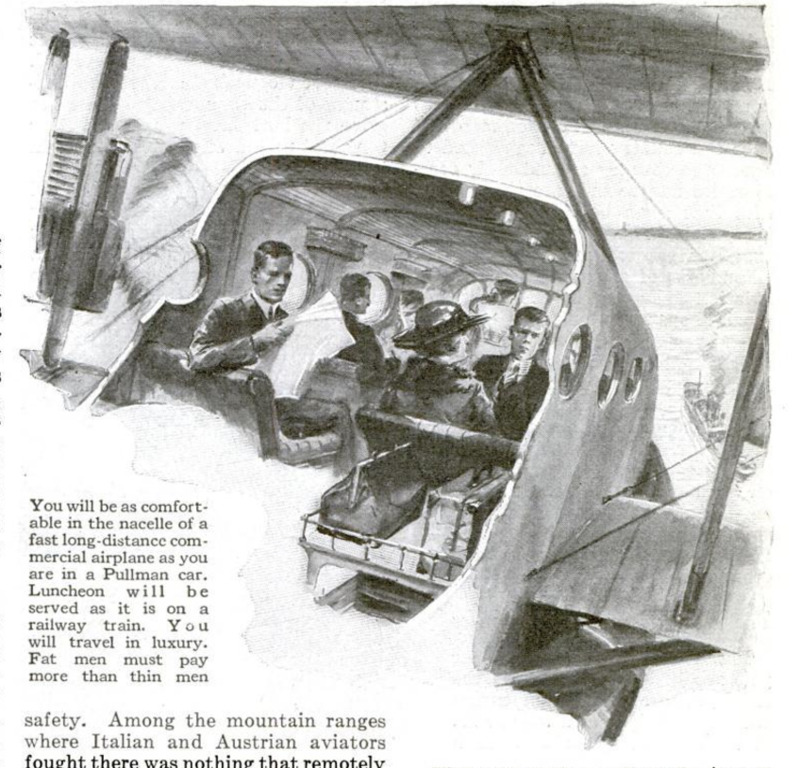

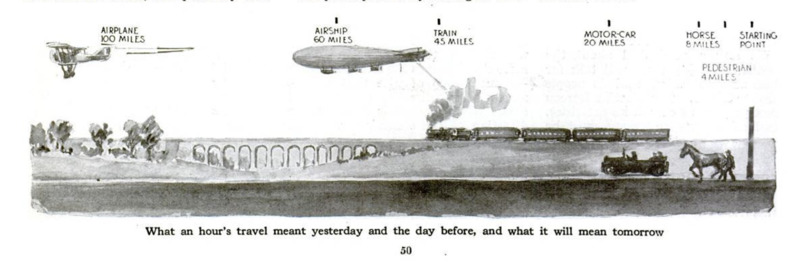

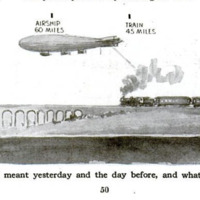

Regular passenger trips are now

made between London and Paris and

between Paris and Brussels. Rome

can be reached from London in twelve

and a half hours instead of in forty-

two as at present; and Marseilles in

eight instead of twenty-three. From

London to Constantinople the distance

is but twenty hours by airplane, com-

pared with seventy-two by rail. The

machines planned for this service are

vessels of moderate size equipped with

three hundred horsepower engines.

They ought to carry forty-four hun<

dred pounds of revenue-paying load

in addition to the pilot, mechanic,

and fuel. The cost per passenger mile

would be a little less than $2.75.

There is no reason why the peace

plane should not be far cheaper than

the fighting war plane. Remember

that the fighting machine had to be

extraordinarily light. It was not in-

tended to stay in the air more than two

or three hours. But a limited amount

of fuel was carried in order that its

climbing ability might not be im-

paired. Even the amount of am-

munition for its machine-gun was

limited.

The peace plane may be larger. This

means that strength may be attained

more easily and cheaply than in the

small gnat-like fighter. The acrobatic

performances of the fighting pilot—

his “vrilles,” his loops, his Immelmann

turns, his barrel rolls, his falling-leaf

drops —will play no part in the less

thrilling career of the commercial

pilot. Therefore outrageous demands

need not be made on the peace ma-

chine. All this tends to simplicity and

cheapness of construction without re-

ducing the factor of safety.

Perhaps, instead of the multi-engine

machine, we may have an airplane

that has an éngine used for flying and

an auxiliary source of power to be

utilized when the main plant fails.

Who knows but this auxiliary engine

may be driven by steam stored under

pressure—a_practice now, followed in

many factories where fireless super-

heated steam locomotives are used?

Certainly the multi-engine machine

would be far less economical than a

machine equipped with a single flying

motor supplemented by an wuxiliary

engine,

Will Commercial Flying Pay ?

Will commercial flying pay? People

asked themselves a hundred years ago:

Will railways pay? Flying will pay

simply because it is fast. Only the

other day the owner of great London

department-store flew to Brussels in

order to hold a conference with his

branch manager there. He saved

days in actual time and thousands in

‘money—so he later reported.

Whenever the object to be gained

is dependent on the saving of time, it

will pay to travel by air. It will be

expensive, to be sure, to convey one,

threo or five passengers a distance of

five hundred, a thousand, or fifteen

hundred miles. What if the fare is

two hundred dollars, five hundred

dollars, or even a thousand dollars, in

comparison with the profits to be

made in furthering an enterprise that

means a return of perhaps millions?

Who would not be willing to pay one

dollar to have an important letter

conveyed by air from New York to

Chicago in order to receive a reply

the following night at the cost of

another dollar?

-

Autore secondario

-

Waldemar Kaempffert (writer)

-

Carl Dienstbach (writer)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1919-10

-

pagine

-

47-50

-

Diritti

-

Public Domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by

-

Davide Donà

-

Alberto Bordignon (Supervisor)