-

Titolo

-

Lighthouses, buoys, and other navigational aids guide ships and maintain them away from dangerous spots during wartime

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Title: War leaves its mark on the signposts of the sea

-

Subititle: The Coast Guard has a big job in maintaining our lighthouses, buoys, and other navigational aids under wartime pressure

-

extracted text

-

IN TIME of peace, the U.S,

Coast Guard maintains

thousands of aids to navi-

gation — lighthouses, light-

ships, radio beacons, buoys,

and channel markers—up |

and down our coasts and in

Alaska and our other pos-

sessions. With the war, this |

division of Coast Guard |

work has doubled and re-

doubled, taking on new im-

portance and new dangers.

In distant harbors all over |

the world, the Coast Guard

has had to survey and mark |

channels, harbors, and mine

flelds, its men working in

frequent danger of sub-

marine or air attack from

the enemy. In our own

waters, also, its job has

doubled as shipping has in- |

creased by leaps and bounds

and as harbor-defense works

have introduced new haz-

ards to navigation. |

Basically, the job of all |

navigation aids is to guide

ships along the coast and

into our harbors by warn-

ing them away from dan. |

gerous spots. In peacetime, |

such dangers are presented

by rocks, shoals, wrecks,

and similar obstructions. In

wartime, there are the added

complications of mine fields,

antisubmarine nets, and

new anchorages required by

convoys at their points of rendezvous.

Many of the devices used by the Coast

Guard are swathed in secrecy. Should their

details fall into the hands of the enemy,

they might aid submarines to destroy

whole convoys of our ships. But the Coast

Guard, and all navigators, still place their

greatest reliance upon such devices as light

houses and buoys, whose basic principles

were developed long before the war, but

whose operation has been modified to meet

wartime conditions.

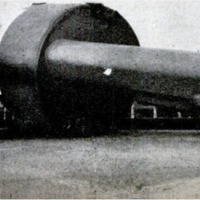

At the outbreak of the war, there were

more than 17,000 buoys in use along our

coast; today, this number has been sub-

stantially increased. Buoys differ widely

in size, shape, and type, and each has its

special significance and meaning to the

‘mariner.

As a ship comes toward a harbor, the

navigator steers a course between two

buoys which mark the entrance to the

channel, a conical red “nun” buoy marking

the right-hand margin, a cylindrical black

“can” buoy marking the left. These may

be located far out to sea, but once the

‘mariner has found these buoys his course is

clear, for always within sight or sound

will be the next pair of channel markers,

until he has found his way to a dock or safe

anchorage. Buoys with red and black

horizontal bands indicate obstructions or

channel junctions.

Other colors are used for special purposes.

White buoys mark anchorages; yellow ones,

quarantine anchorages. A white buoy with a

green top signifies an area in which dredging

is being carried on. A black and white, hori-

zontally banded buoy marks the limits of areas

in which fish nets or traps are permitted.

A large proportion of all buoys carry lights

50 that they can be seen by mariners at night.

Here again color is important, green lights

marking the left sides of channels as you go

in, and red lights the right sides. To further

facilitate identification, flashing lights are

often used so that the navigator, in the dark

of night, may distinguish one buoy from an-

other, or slowly flashing lights indicate the

regular channel markers,

Quick-flashing lights—60 or more flashes

per minute—are placed at sharp turns or sudden

constrictions of the channel and call for special

caution. If the light consists of quick flashes

interrupted by dark intervals of about four

seconds between flash groups, the navigator

knows that he is heading toward some obstruc-

tion or a junction of channels. Short and long

flashes alternating mark the center of a wide

channel, and tell the navigator that he should

pass close to the buoy for greater safety.

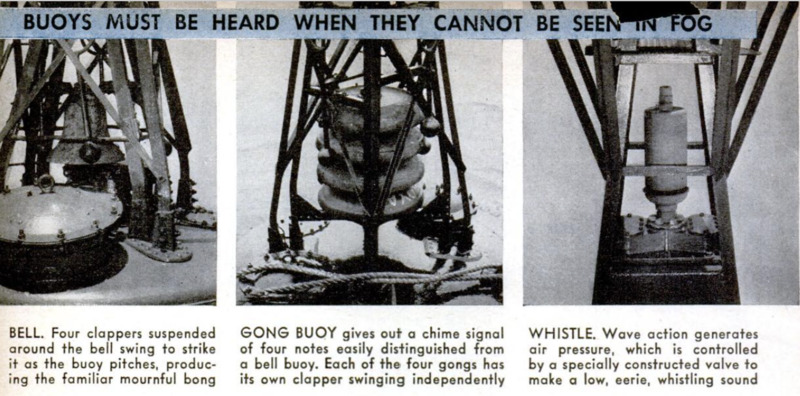

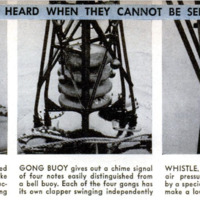

‘While lights on buoys facilitate nighttime navi-

gation in good weather, sound is utilized to

achieve a similar end in fog or storm. Thus,

lighted and unlighted buoys at important points

are equipped with whistles, bells, or gongs oper-

ated by the motion of the buoy in the water.

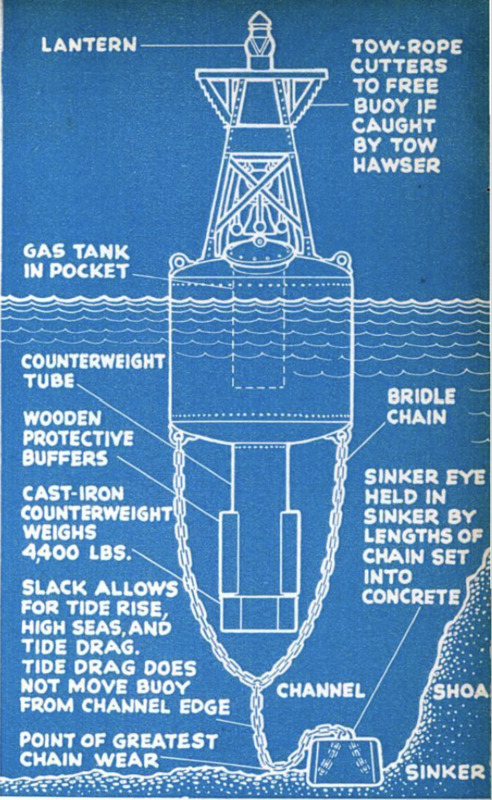

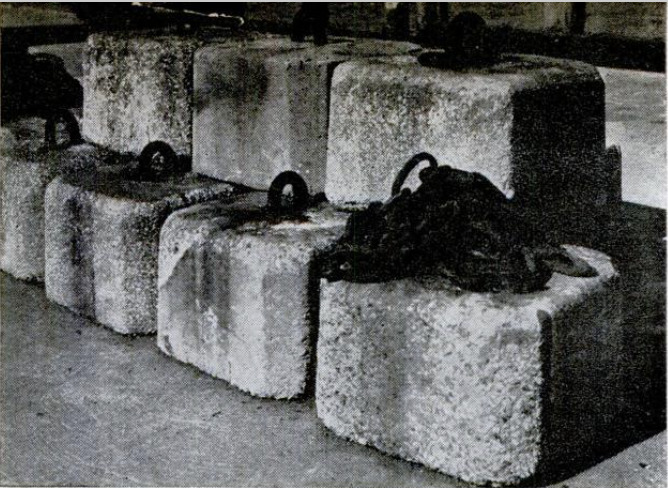

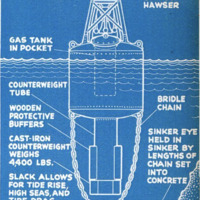

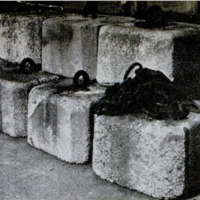

More than 107 types of buoys have been de-

veloped to cope with differing conditions met at

various buoy locations. Very large buoys must

be used in deep water to support the long chain

which connects the buoy to its anchor on the

bed of the sea. Smaller, extremely rugged units

are moored in rough, shallow waters, and are

designed with low centers of gravity to remain

nearly upright despite the heavy pitching of the

waves. Broad, round-bottomed buoys are used

in shallow waters.

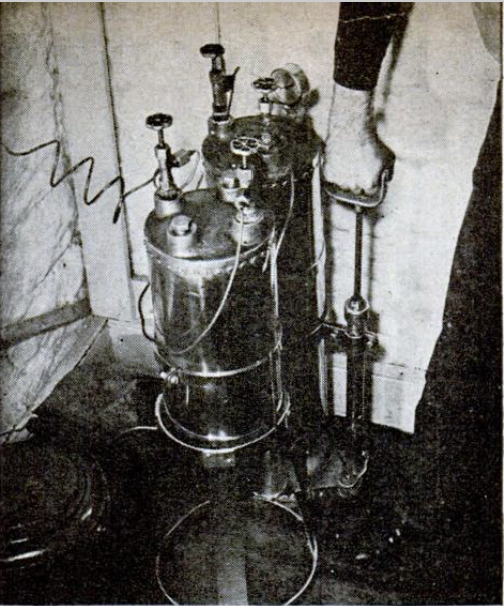

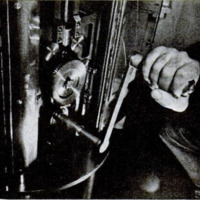

Both electricity and acetylene gas are

utilized to operate buoy lights. When acety-

lene is used, large tanks of gas under pres-

sures as high as 14 atmospheres are placed

in special receptacles in the body of the

buoy. A tiny light burns constantly, al-

though this is invisible to the navigator. A

clockwork mechanism causes gas to be fed

into the burning chamber in short puffs.

Here it is set off by the pilot light, the

mechanism being so adjusted as to provide

the predetermined quick or slow or inter-

rupted flashes. The flame itself is small—

less than an inch in length, but it is magni-

fied and concentrated by the lenses Which

surround it so that it shines with great

brilliance over a considerable area of sea.

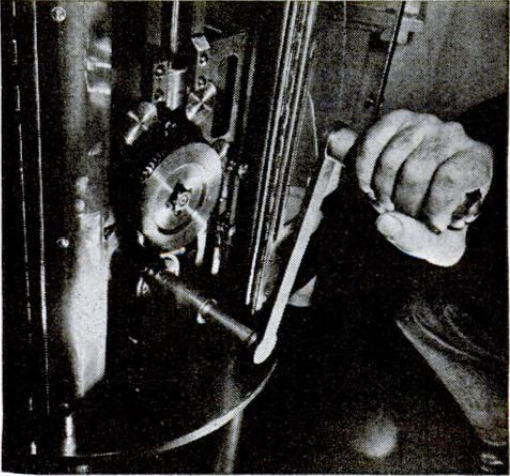

When electricity is used, a special mecha-

nism in the buoy automatically replaces

burnt-out bulbs. Whenever the circuit can-

mot be completed because of bulb failure,

the device instantly makes a partial revolu-

tion, bringing a new bulb into contact.

With such devices, it is possible for buoys

to remain unattended for many months—

sometimes for as long as a year. In war-

time, however, buoys are exposed to hazards

from drifting mines, debris, and derelicts,

and from the impact of ships guided by

navigators in unfamiliar harbors. To meet

these added hazards, the Coast Guard has

had to multiply its buoy inspection and

servicing trips.

It has also developed many special buoys.

One of these is a can or nun buoy topped

with a specially designed prismatic reflect-

ing paper. At night this buoy cannot be

seen, since it casts no light of its own.

An enemy ship or submarine trying to make

its way into a harbor would have to dis-

close its own position before it could find

such a buoy. However, a ship on a legiti-

mate mission can quickly locate these de-

vices by sweeping the sea with even a small

flashlight, for the reflecting paper picks up

any light that strikes its surface.

Frequently, war conditions have required

the redesigning of standard types of buoys.

For instance, buoys used to support sub-

marine nets are sometimes drawn far out of

plumb by the tug of the net itself. If

equipped with standard light mechanisms,

such buoys would cast their light at an

angle invisible from the channel. To over-

come this difficulty, special tripods have

been developed which hold the lights in a

suitable horizontal position despite the dis-

torted tilt of the base buoy.

Lightships and lighthouses are designed

to support a light at great height above

the sea. They usually are placed at en-

trances to harbors, or at isolated danger

pointa from which it is necessary to warn

mariners away.

Today, most lighthouses also house fog

signals bells, whistles, or horns—and radio-

beacon equipment. War has brought an end

to the traditional loneliness of the light-

house keeper, for now most lighthouses have

‘augmented staffs operating the special equip-

‘ment essential fn wartime for detection and

recognition of incoming vessels.

Lighthouse signals have their own char-

acteristics, just as do those of buoys. Some

show a continuous, steady light. Others flash

at regular intervals. SUIl others fre up

at intervals with flashes of greater brilliance

than thelr continuous light. Sometimes an

alternation of colors Is used.

All these differences aid the mariner in

recognizing the light which marks his land-

fall.” Once he has identified the light, n

reforence to his charts will give him his

position within a few yards.

The flashing lights of lighthouses are

produced In several ways. In some cases

the flashes result from the rotation of lenses

in which various flash panels are incorpo-

rated. Tn large lighthouses, where electricity

is the illuminant, timing devices interrupt

the flow of current or conceal the light

source at definite intervals.

In minor lights, where acetylene gas is

used, the flashes are produced by interrupt-

ing the flow of gas With a bellows-like de-

vice, each small charge of gus being ignited

by & constantly burning, nonluminous pilot

flame.

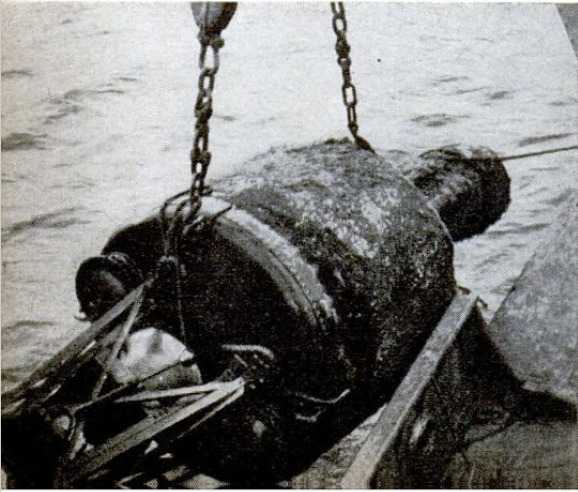

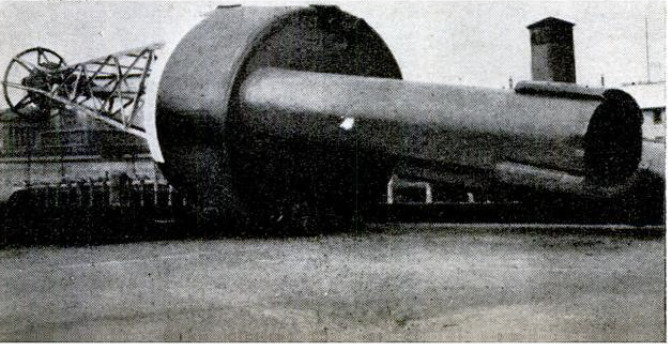

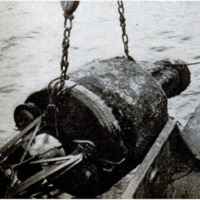

To service lighthouses, lightships, and

buoys, the Coast Guard operates large fleets

of tenders and cutters—sturdy little ships

capable of carrying heavy buoys on their

decks and equipped with derricks which

can lift the full weight of a buoy, its long

anchor chain, and its anchor. These vessels

are specially designed to navigate in shallow

waters and close to dangerous underwater

obstructions. Their sturdy hulls can with-

stand battering contact with the stone or

steel walls of lighthouse structures, under

the roughest conditions of sea. Frequently,

they must go far out to rescue buoys which

have been cast free from their anchors by

collision or storm. For such buoys—their

lights still flashing—might serve as false

beacons when once they leave their moor-

ings and cause the wreck of the very ships

they were designed to save.

-

Autore secondario

-

Albert Q. Maisel (article writer)

-

Robert F. Smith (photographer)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1944-03

-

pagine

-

104-108, 191

-

Diritti

-

Public Domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by

-

Lorenzo Chinellato

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Immagine 2022-04-25 143720.png

Immagine 2022-04-25 143720.png Immagine 2022-04-25 143947.png

Immagine 2022-04-25 143947.png Immagine 2022-04-25 143738.png

Immagine 2022-04-25 143738.png Immagine 2022-04-25 143919.png

Immagine 2022-04-25 143919.png Immagine 2022-04-25 143750.png

Immagine 2022-04-25 143750.png Immagine 2022-04-25 143804.png

Immagine 2022-04-25 143804.png Immagine 2022-04-25 143829.png

Immagine 2022-04-25 143829.png Immagine 2022-04-25 143844.png

Immagine 2022-04-25 143844.png Immagine 2022-04-25 143855.png

Immagine 2022-04-25 143855.png Immagine 2022-04-25 143908.png

Immagine 2022-04-25 143908.png Immagine 2022-04-25 143934.png

Immagine 2022-04-25 143934.png Immagine 2022-04-25 144004.png

Immagine 2022-04-25 144004.png Immagine 2022-04-25 144017.png

Immagine 2022-04-25 144017.png Immagine 2022-04-25 144029.png

Immagine 2022-04-25 144029.png Immagine 2022-04-25 144045.png

Immagine 2022-04-25 144045.png Immagine 2022-04-25 144056.png

Immagine 2022-04-25 144056.png