Topographical engineers create maps assembling air photos in less than 20 hours after order

Contenuto

-

Titolo

-

Topographical engineers create maps assembling air photos in less than 20 hours after order

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Title: The general gets his map

-

Subtitle: Topographical engineers perform a 20-hour miracle to chart the path to victory in fast-moving attack

-

extracted text

-

RECONNAISSANCE radio flashes the

news. Retreating enemy forces, hard-

pressed on the flanks and pounded in the

middle, have blown up the great bridge,

cutting off pursuit by our armored division.

It could be a serious setback. But let's

see how an American general will handle it.

Minutes after receiving the news, the

general dictates an order. It's a curious

order. He doesn't want assault boats, bridge

repairmen, or amphibious jeeps. He wants

a map—a particular kind of map—at once.

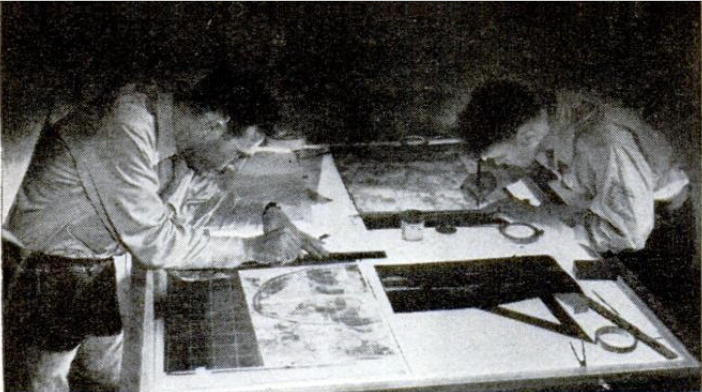

To the rear, in carefully camouflaged

operational position, topographical engineers

await just such an order. The boss of the

outfit is an alert young lieutenant. His

company functions like a miniature bat-

talion. It has three platoons—one for field

survey, another for camera-reproduction

work, and the third comprising computers,

draftsmen, and photographers. They are all

alert for the call that comes clicking into

the command-post tent.

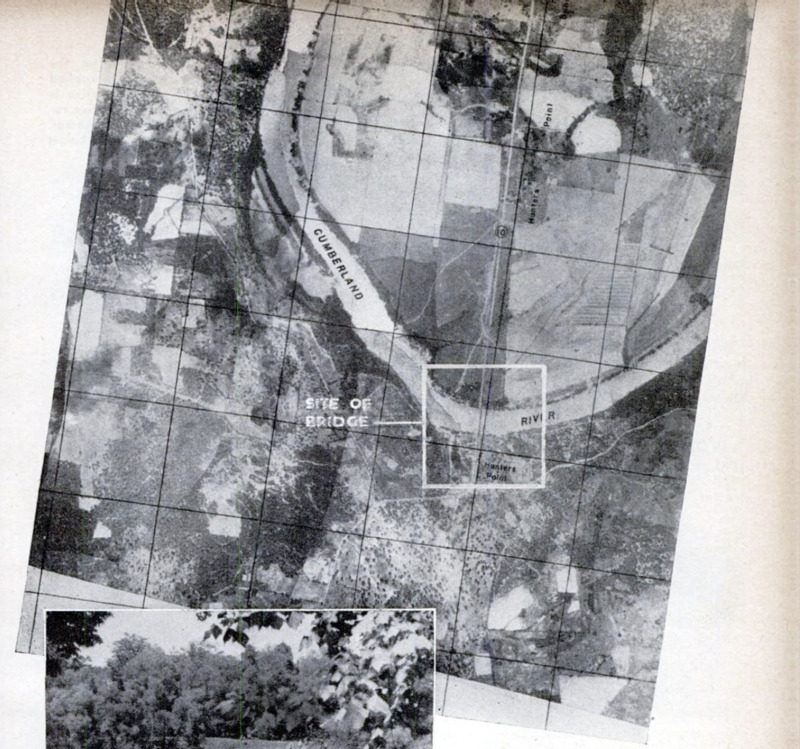

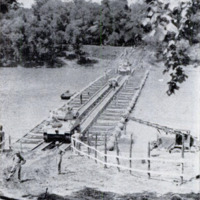

It reads: “Rush photo map HP-C area

showing bridge site and vicinity both sides

river. Prepare 5,000 copies immediate de-

livery our units here.”

The lieutenant immediately puts through

a request to air-support command for aerial

photographs of the area.

At air-support headquarters, a young re-

connaissance pilot is assigned to the mis-

sion. He's off in a cloud of dust, and soon

his automatic, oblique-set camera is clicking

sequence shots of the bridge area below. He

lays his course carefully, shooting the area.

in strips as he flies back and forth. A 60-

percent overlap is allowed on each strip

to give the map makers plenty of prints to

work with. “Shooting” completed, the pilot

stuffs the film into a tube and lets it para-

chute down over “Topo” headquarters,

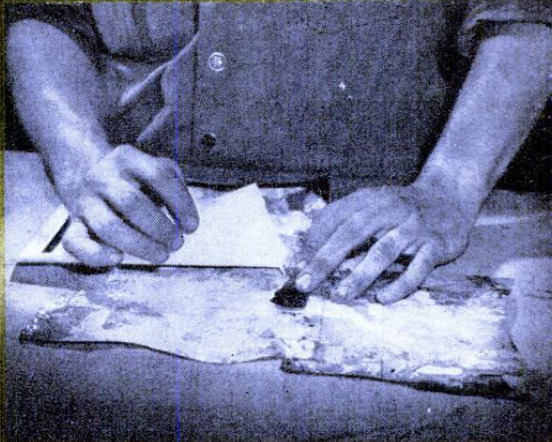

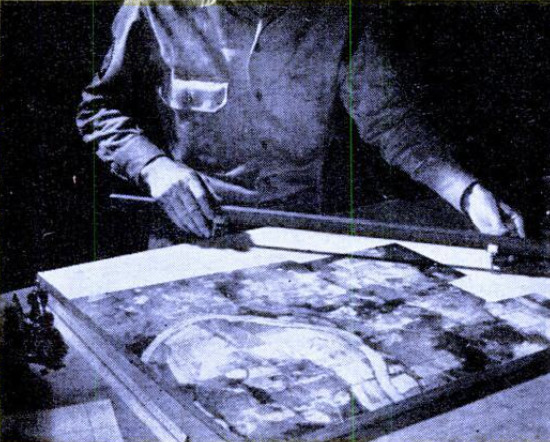

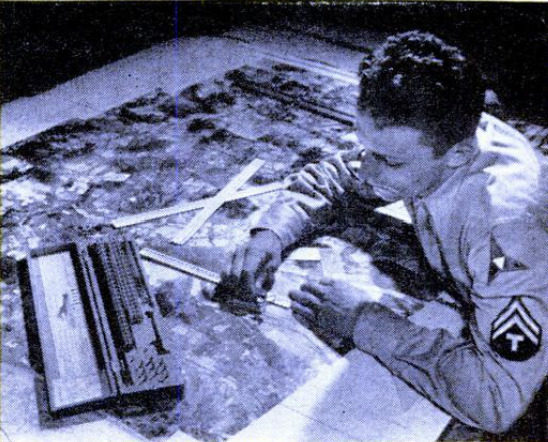

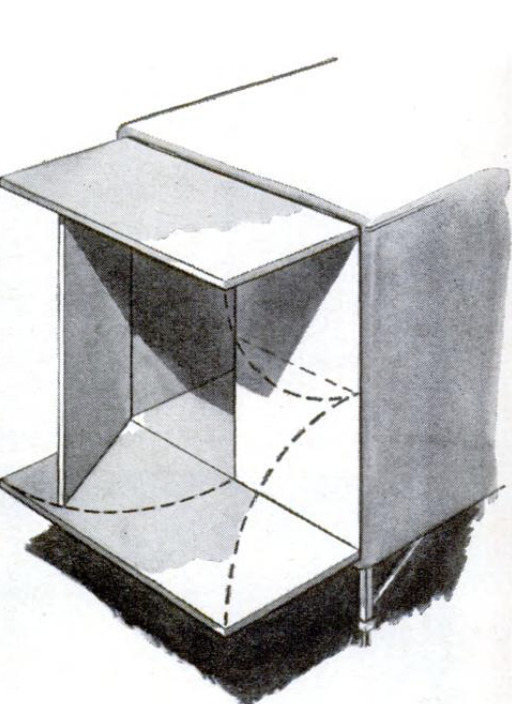

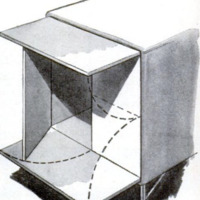

Map makers are waiting. This is where

they go to work. Their step-by-step pro-

gress is shown on these pages in pictures

and drawings. The miracle: Less than 20

hours after the general's order arrives, 1e

topographical engineers have placed in their

commander's hands a slick, 20 by 2214-inch

mosaic of the bridge area, and 5,000 copies

have reached the units concerned. Should

more be required, they can be run off at the

rate of 5,000 an hour.

But why the map? It's the general's key

to future operations. It tells him at a glance

the safest, most practical point at which to

fling a ponton bridge across the stream. It

shows him the exact width of the river at

that point. Revealing the position of the

enemy with relation to this operation, the

map indicates how much armed protection

will be necessary. It shows the situation of

roads on the opposite river bank

and, equally important, what to

expect in the way of natw al con-

cealment for assault troops estah-

lishing the bridgehead. With the

map before him, the general

knows just what to do to over-

come the temporary advantage

achieved by the enemy in blow-

ing up the big bridge. His orders

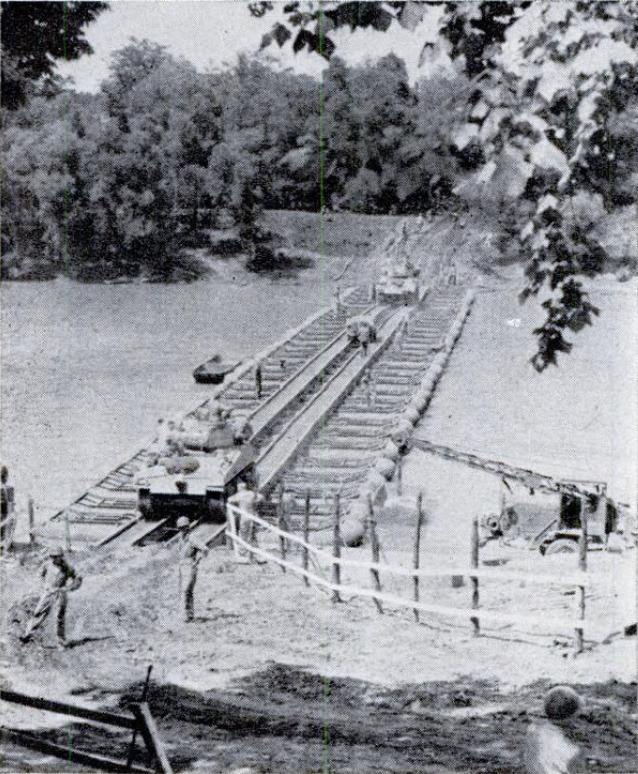

rattle off—and, only three hours

from the time he received the

photo map, our armor goes pound-

ing across a new bridge to take

up the pursuit of the enemy. Con-

structed of pontons and steel, the

bridge can be built to span as

much as 330 feet of water.

-

Autore secondario

-

Jack O'Brine (article writer)

-

William W. Morris (photographer)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1944-03

-

pagine

-

111-113

-

Diritti

-

Public Domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by

-

Lorenzo Chinellato

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)