-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

A Visit to Davy Jones's Locker. Going down in a submarine - Walking on the bed og the ocean - How the war's lost ships are to be recovered

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

A Visit to Davy Jones's Locker. Going down in a submarine - Walking on the bed og the ocean - How the war's lost ships are to be recovered

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

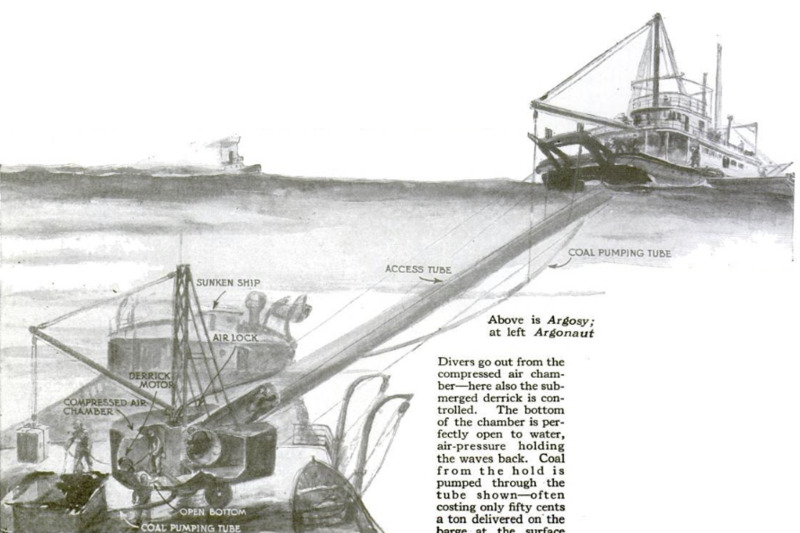

GETTING down into

thesubmarine Argo-

nawt is no very diffi-

cult process. You clamber

up into an open hatchway

at the front of the Argosy,

and find yourself at the

mouth of a huge steel pipe,

four and a half feet in

diameter. Descending the

pipe is a good deal like go-

ing down an ordinary stair-

way. Really, it is a kind of

half-ladder, half-stairway. Angle-irons

riveted to the wall are the steps.

After descending about ten feet you

find yourself at an elbow in the pipe.

It stops going straight down and heads

off toward the Argonaut, the particular

angle downward depending on the

amount she happens to be submerged

at the moment. Electric lights illumi-

nate the passageway.

At the far end is a steel wall barring

progress. At the right, however, and

within the huge joint which holds the

access tube to the Argonaut, there is a

round opening, about two feet in di-

ameter, which leads to the “air-lock,”

a chamber about seven feet long, three

feet wide, and four and a half feet high.

At the far end of the air-lock is the door

leading to the actual working chamber

itself. This door is closed. There is a

heavy air-pressure on the other side—

needed to prevent the water from

entering through the hole in the

floor of the working chamber. This is

about four feet by two and a quarter

feet in size. Through it the actual

operations on the bottom of the ocean

or on a submerged ship are carried on. -

As is evident, the air-pressure in the

little room you have just crawled into

must equal that within the actual

working chamber itself, or you would

never get the door between the two

open. This is precisely what this little

room, the “air-lock,” is for. Like the

lock in a canal through which a ship

passes to gain a higher level, so this

air-lock exists to raise the air-pressure

that surrounds you up to the higher

level of that within the working cham-

ber. The door between you and the

latter is thirty-eight inches long by

twenty-three inches wide—say 875

square inches in total area. For every

foot that one goes down into the

water, the pressure increases by .434

pounds. If one were down 25 feet

then, the pressure would be 10.85

pounds per square inch more than

the approximately fifteen

pounds per square inch al-

‘ways on the earth’s surface.

If the door has an area of

875 square inches, as we

figured, and there is a push

of 10.85 pounds on each

square inch, it appears that

there is a total of 8,750

pounds pushing on the

whole door, roughly—about

four and a half tons! Obvi-

ously you couldn’t get the

door open and yourself into the operat-

ing chamber without the use of this in-

tervening air-lock. Using the, air-lock,

one can get'up a balancing- pressure

and overcome the four and a half tons.

Once inside the air-lock, the door is

closed behind you. It is locked from

the inside. Simon Lake seizes a piece

of heavy iron bar lying on the floor,

and pounds the door and the locks

even tighter. This is to make sure

no air escapes. He then turns a valve.

It gives you a creepy sensation—

turning that valve. You know how a

chicken must feel when he sees the axe

descending. But it is only momentary.

In comes the air. P-

tsh-h-h—sh-h-h-h-h-h-h-h-h.

It is the same kind of a |

sound, though not quite so |

great in volume, that a |

locomotive makes when it

draws up to a station and

the safety valve starts to

blow off because the engi- |

neer is no longer using the

steam. in his cylinders.

In that little room the |

noise is deafening.

Suddenly the air is shut |

off. Inthe meantime you

have been swallowing, pinching your

nese, and endeavoring to get the Eus-

tachian tubes that lead from your

throat to your ears under the same air-

pressure as that coming into the room.

Otherwise your ear-drums would pro-

test unmistakably against the pressure.

Mr. Lake has shut off the air, so

you may have a few moments in which

to accustom yourself to the increased

pressure. Then he reaches for the

valve again.

P-t-sh-h-h-h-h! On it comes again.

In a few moments it begins to lose its

sharp whistle, eases off into a long-

drawn-out sigh, and then ceases alto-

gether. The reason for this is that the

air has been coming ‘rom the

working chamber, and now

ceases because the pressures in

the two rooms have become

equal. Obviously it should

now be possible to open the

door connecting the two. You

find that Mr. Lake is already

pounding on the doors latches.

Afew more pounds, and presto!

the door swings ‘open. The

air-lock has served its purpose

—let you conquer the barrier.

You and the others scramble

through the opening.

You find yourself in a little

steel-riveted, steel-plated room,

shaped as to floor and ceiling a

good deal like the bottom of a

fiat-iron, and about seven feet

high. In reality it is the

grow of the underwater boat.

is accounts for its triangular

or flat-iron shape.

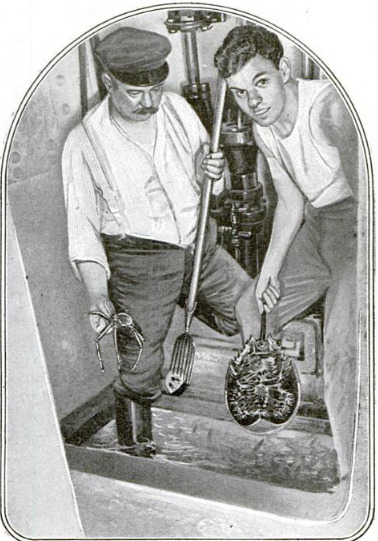

The Hole in the Floor

But the thing that attracts

your attention above all else in

the room is a hole in the floor

about two and a fourth by four

feet. There is water in that

hole. There are all kinds of

shells lying down there, stones,

and many weird objects.

It's the bottom of the ocean

you're looking at. Suddenly

some kind of sea-denizen that

probably calls himself a crab

of a sort heaves into view. He

has a shell on his back, and

four or five legs sticking out on each

side, and all told, legs and all, he is

about as big as the palm of your hand.

Evidently local society down here dis-

dains to go forward and backward as

is the custom in regions above, for he

or she locomotes sideways, and really

can dart through the water at a re-

markable pace even though side-

stepping it all the while. Interesting

customs the natives have down here.

A fish comes plowing into view. He

apparently doesn’t like the scenery

just above him, and veers off and out

of sight. It’s lucky for him he did, for

Mr. Lake is already standing over the

opening, waiting, a spear in his hand,

for anything that may come along.

Look! Here comes something

crawling over the bed of the sea. It

looks like an army tank headed for

somewhere. It has a big horseshoe-

shaped shell, and you can't see any

legs, or wheels, or anything under it.

You wonder how it gets along. Down

shoots Mr. Lake's spear and Mr. or

Mrs. Sea Tank is impaled as easily as

if Mr. Lake had been aiming for the

middle of a fried egg with a table fork.

Up comes spear, sea tank and all. It

proves to be a huge horseshoe crab,

more than a foot across. What appear

to be about two dozen legs wave wildly

from each side of the shell as you pull;

it off the spear. You put the crab

bottom upward on the floor of the

boat where it can kick up its heels to

its heart's content, and no harm done,

for it is in the same predicament a

turtle is when turned over on its back.

It dawns on you that you have for-

gotten you are under considerable air-

pressure. It has all been so interest-

ing, looking down through that open-

ing on to the bed of the ocean, you

have forgotten all about anything else.

The truth is, the air-pressure within

the far corners of your lungs, and at

the back of your ear-drums has be-

come the same as that within the

room, and, except for a general sensa-

tion of heaviness, it is not noticeable.

Standing in that chamber and look-

ing through the opening in the floor,

one can realize very readily how it

would be if one happened to pass over

asubmerged wreck. Nearly the whole

vessel would stand out as plainly as a

board at the bottom of a brook. Itis

really remarkable how much light gets

to the bottom of the sea at ordinary

depths. Most sea water, Mr. Lake

says, is quite clear, in spite of the fact

that one has a hard time realizing it

when trying to look down into it from

a boat at the surface. In Southern

waters, particularly, one can fre-

quently see two or three hundred feet

with ease.

To Salvage Wrecks

Had there been wrecks close

at hand in Bridgeport Harbor,

it would have been possible to

get over one, and perhaps walk

on its deck. As it is, you may

take off your shoes and stock-

ings and stand in the opening,

walking on the bed of the

ocean as the submarine moves

along. You can get a very

good idea of how easy it would

be to size up the condition of a

sunken ship, get things from

its interior, send out divers,

and otherwise work with it,

almost as easily as if it were

but two or three feet under the

surface. You have to concede

that Simon Lake has turned

out an exceedingly practical

contrivance; and one of strik-

ing originality.

‘What Mr. Lake is going to

do with his Argosy and Argo-

naut is perhaps best made

evident by the following quota-

tions from his book, “The

Submarine in War and Peace”:

Somewhere off Bridgeport,

Conn,, lies the wreck of the old

Sound steamer Lezington. Tradi-

tion has it that she has a fortune in

her safe. Many a ship has been

sunk in the waters about Hell

Gate; search was carried on there

for years for the old British

frigate Hussar, which struck on

Pot Rock and sank during the Revolution-

ary War. They tell that she had four

million dollars (£820,000) in gold on board

to pay off the British troops, and that she

carried this treasure to the bottom with

her. There is a cargo of block tin in a

barge somewhere off the Battery, New

York, and many a ship with valuable cargo

lies along the coast from Newfoundland to

Key West. The yearly loss in ships and

cargoes throughout the world has always

run into’many millions of dollars, and since

the war this has been multiplied a hundred-

fold, amounting to billions. The time will

come when many of these ships will be

found, and such of their cargo as is still

valuable will be salvaged.

“Ships like the Argosy and Argonaut

will get this booty,” says Mr. Lake.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Lloyd E. Darling (writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1919-10

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

78-79

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Davide Donà

-

Alberto Bordignon (Supervisor)

Popular Science Monthly, v. 95, n. 4, 1919

Popular Science Monthly, v. 95, n. 4, 1919