-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

The celestial Navigation Trainer, a flight simulator for students

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Title: Bombing Tokyo from a silo

-

Subtitle: Even a veteran combat pilot gets a thrill out of flying a mission in the Air Force's magic carpet, The Celestial Navigation Trainer

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

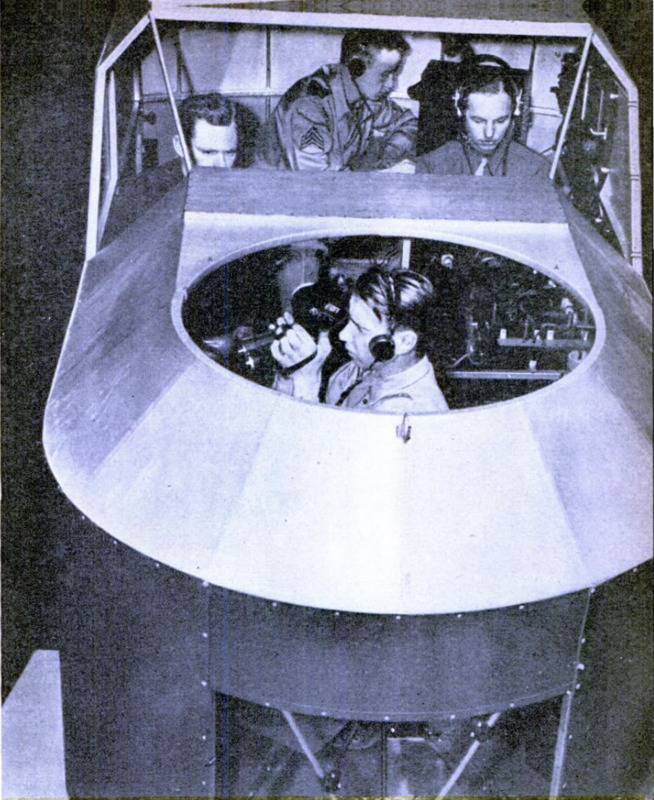

THE other day, I took off in a four-

engine ship, maneuvered to altitude.

Crossing the Atlantic Ocean, Africa,

the Arabian Sea, India, Burma, and China, I

bombed Japan. After I saw my bombs blast

Tokyo, I could have flown on over Kam-

chatka, along the Aleutians to Alaska, then

home to Florida. After all this, though,

I climbed down the ladder from my ship and

~~

found that I had made a landing in a silo.

No, it wasn’t a dream. It actually hap-

pened—and I'll tell you how.

It began the other day, when I saw, for

the first time, several peculiar-looking build-

ings which rise from Florida's flat, sandy

terrain. They look just like the familiar

grain silos of our breadbasket cduntry of

the Middle West, or the friendly réd ele-

vators of Saskatchewan. They are about

40 feet high—cylindrical and with hemi-

spherical domes; you can see the domes

revolving. The whole thing looks like an observatory. Ac-

tually, it is the School of Applied Tactics of the Army Air

Forces—AAFSAT for short.

The first time I saw these strange-looking houses, I thought

we'd gone into the grain business, but when I strolled through

the open door of one I found an air-conditioned classroom.

The interior was light-sealed and, with the door closed, real

darkness pushed in on me. When the lights were turned on,

I saw the Celestial Navigation Trainer, a glorified Link

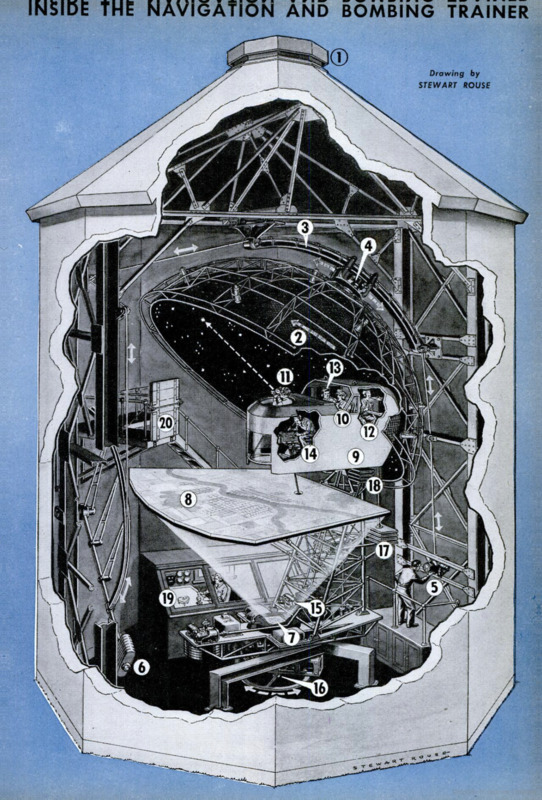

Trainer, rising frcm a heavy concrete base. High above,

supported by a tower on a revolving platform, was the

fuselage of the “plane.”

This fuselage, I found later, was attached to the top of the

column by a universal joint, which made possible the pitching

and banking of simulated flight. Beneath the airplane was a

screen, or terrain plate, which received the projected images

representing any part of the earth’s surface. I heard that

those scenes appeared as if actually viewed from an airplane

at 10,000 feet, but others could be projected with any altitude

desired. Images of clouds in any given density could be

thrown upon the same screen. Drift from anticipated cross

winds, or resultants of head winds or tail winds, could also

be introduced.

Above the ship, I saw the hemispherical dome, made of

chicken wire and holding the lights representing the stars

used for navigation. There were also the outlines of the

constellations. This dome could be rotated and moved on

machined rollers over the dome rail to simulate the passage

of time or the change in longitude and latitude. The axis of

the sphere, half of which was represented by the dome, fell

within the fuselage of the trainer, and thus, by using his

bubble sextant, the navigator could determine accurately

the altitudes of the collimated “stars.”

In a lighted booth, under the ship, was an operator's desk.

There I saw various switches and controls by which the at-

tendant moved the dome and terrain plate. He also controlled

the radio to introduce problems of actual flying; he could

even simulate two radio stations for obtaining bearings within

the ship. An automatic recording gadget traced the flight path.

The cockpit of the trainer was that of a four-engine bomber.

I entered with my crew—pilot, copilot, navigator, hombar-

dier, and radio operator—and we sat in our usual places for

a combat mission. As we started the engines, there came

the noise of real engines breaking into life, and I felt the

steady vibrations. Every instrument was on the dashboard.

Over the radio, the operator called, “All clear for take-off.” T

checked the fuel gauges and noted that they actually func-

tioned. I heard the operator call for the dome to be set for

our flight, and he turned on the time and navigation switches.

That set up a motion of the dome, corresponding exactly

to the change in the heavens visible to an observer moving

at the same speed and in the same direction as the simulated

flight of the trainer. A motor began to turn the dome from

east to west at a rate equal to the change in longitude. This,

of course, depended on the east-west course and the ground

speed. At the same time, the latitude drive moved the dome

up or down at a rate equal to the change in latitude caused by

the north-south course of the ship. Automatically, the dome

gear box compensated for the apparent motion, east or west,

of the stars.

Taking off in the silo, I had every sensation of flight, and

as I looked at the lighted projection in front of the wind-

shield, I saw the trees rushing back toward us—and I al-

most ducked as they went by, close

underneath, Now I saw the first navigation

chart projected on the screen. As the hours

dragged by to the steady drone of the

engines, I watched the fuel “simulatedly”

used up. With the help of my copilot, I

adjusted the throttle for best economy; we

had a long trip ahead. I set the turbos and

the manometers, and tuned in the radio fora

broadcast to pass the time. Later, I noted

that the local radio for Orlando, Fla., was

even made to fade. Then the operator tuned |

in on our first destination, Trinidad. The RDF

needle became more and more sensitive as

we approached South America. In seven |

hours, the coast of this continent, seemingly

coming out of the blue-green Caribbean, slid

under the ship on the screen. We had been

averaging 300 miles an hour and, as Port

of Spain went below, we even followed the

“military corridor of approach,” for this was

actual training for war. After landing at

Waller Field, we climbed down the ladder to

the ground, to wait while the ship was re-

serviced. Coffee would taste mighty good

now! After all, we'd really been in that

cockpit nearly eight hours. Stepping off the

ladder, we walked through the dim light |

to the open sunshine—the terrain looked

just as green as I expected Trinidad to ap- |

pear, but the pine trees looked too much like

Florida. I saw a couple of Wacs and then |

a Coca-Cola truck and began to come out of

my dreams.

As the days passed, I went on longer navi-

gation flights and finally came to Africa. |

All along that trip I'd look at the dark

heavens where the stars were “simulatedly”

covered with an overcast. The trackless

waste of darkness below could be the ocean

or the black jungle. Every now and then,

I'd hear a voice, “Okay, Joe, turn on the

stars,” and overhead would appear the

friendly collimated lights. I saw our navi- |

gator’s sextant light flash for a few seconds

as he shot our position. I could see the Big

Dipper almost on the horizon, and I knew

we were near the equator. Then I'd prove it |

by finding the Southern Cross, and I'd call |

“Corona Australis” to my navigator to show

him how smart I was. There would be

Cassiopeia and the Pleiades, too. Suddenly

a rude voice called out, “Turn out the stars,”

and overhead they flickered and went out.

It was dark as hell again, and lonesome.

Then there would be the steady drome of |

the engines as we pitched and tossed in a

man-made storm.

When daylight came and I could see the

screen, which was our world, I began to

tense, because the terrain was the approach

to Tokyo. As we made our corrections to

arrive over the initial point for the bombing

run, I heard the rude voice call out, “Turn

on the clouds.” Then quickly, part of the

earth was hidden and dark stratus clouds

drifted across the screen. Through a rift in

them, I saw the island that was our initial

point. I turned to the correct heading, and

there was the target ahead—I had studied

these landmarks so long on my maps that

they were familiar to me. I called my

bombardier on the interphone, “It’s all yours,

George. Take her away.” From there, he

would fly the ship to the target. The rude

voice now called, “Put in the wind drift,”

and the clouds seemed to drift crossways. I

knew then the operator was making it

tough. We now were approaching the target

with it lined up in the bombsight. I heard

and felt the bomb-bay doors opening, and

my heart beat faster. The ship lurched as

I involuntarily pulled back on the wheel.

‘When George called, “Bombs away,” I

took the controls away from the AFCE. It

seemed just like the time we had bombed

Rangoon. I looked out hurriedly into the

blankness of the cockpit windows, half ex-

pecting to see Zeros with their red-circled

insignia gleaming in the sun, but my eyes

met only darkness. As I gazed down at the

city of Tokyo, I ducked my head, for ack-ack

should have been bursting. Then I knew

that the only thing which the inventor had

missed was an automatic gadget down on

the floor to shoot a Very pistol or a Roman

candle at us while the operator fired a few

firecrackers.

Then the bombs struck! After the time

of fall had elapsed, there flashed on the

screen a little light which show their point

of impact. It was perfect! I actually

couldn't control myself—I yelled as loud as

1 could, for our bombs had scored a direct

hit on the Emperor's Palace!

The excitement has been too much for me;

I take evasive action for a few minutes on

the return flight anyway, but I'm just too

fagged out. I turn the ship over to the

younger copilot, who didn’t see it all, and

try to get my nerves settled.

Even after I open the silo door and walk

out into the sunshine of Florida, it's going

to be hard to settle down to an ordinary ex-

istence again. I'm going right down town

and buy a local newspaper, for two reasons:

First, IT want to see what town I'm actually

in; and second, I went to see if Tokyo wasn't

bombed today by a four-engine bomber.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Robert L. Scott Jr. (article writer)

-

Stewart Rouse (illustrator)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1944-04

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

57-59, 198

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public Domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Lorenzo Chinellato

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Popular Science Monthly, v. 144, n. 4, 1944

Popular Science Monthly, v. 144, n. 4, 1944