-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

The Mars seaplane

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Title: The Mars makes good

-

Subtitle: Glenn. L. Martin's flying freighter join the Navy and proves her mettle on a first flight to Hawaii

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

PEARL HARBOR, HAWAII

WE DIDN'T come out to Hawaii just

the ride. We wanted to get the feel

of the peacetime airways that will circle the

globe after the war is won. We wondered

what kind of ships will take the long water

hops on those future trips. That's why we

jumped at the chance when the Navy offered

us permission to take this particular trip.

It was the first transocean flight in regular

service of the giant seaplane Mars.

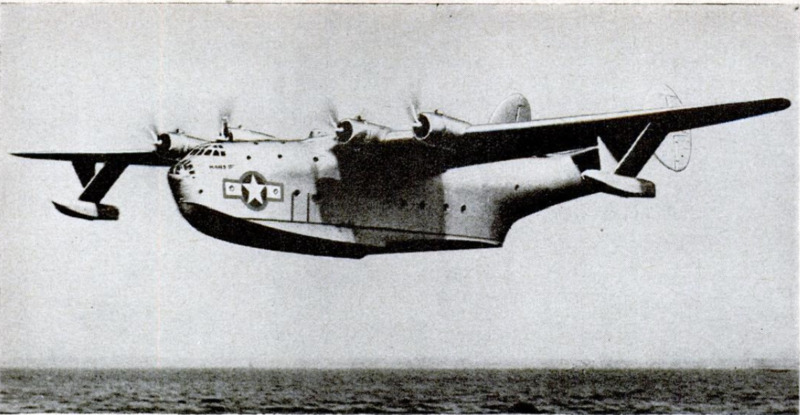

Every one of the 35 people aboard the

huge flying boat had a few lurking doubts

as she cast off her moorings at the Alameda

Naval Air Station on San Francisco Bay.

Only a fool would be confident on the maiden

voyage of any ship of radically new design,

and the Mars is by far the biggest aircraft

in regular service. One hundred seventeen

feet from stem to stern, 200 feet from wing

tip to wing tip, the huge whale-shaped hull

designed by Glenn L. Martin's engineers has

as much room inside as a 15-room house.

The Navy's biggest “flying boxcars,” the

Coronado PB2Y's, are only a little more

than half her size. It would take three giant

Douglas C-54’s to move as much freight or

as many passengers as the Mars can tote on

a 2,500-mile hop. It was a lot of airplane

that Skipper Bill Coney had to lift off of

San Francisco Bay on that clear evening of

January 22—about 75 tons of plane, gas,

crew, and cargo.

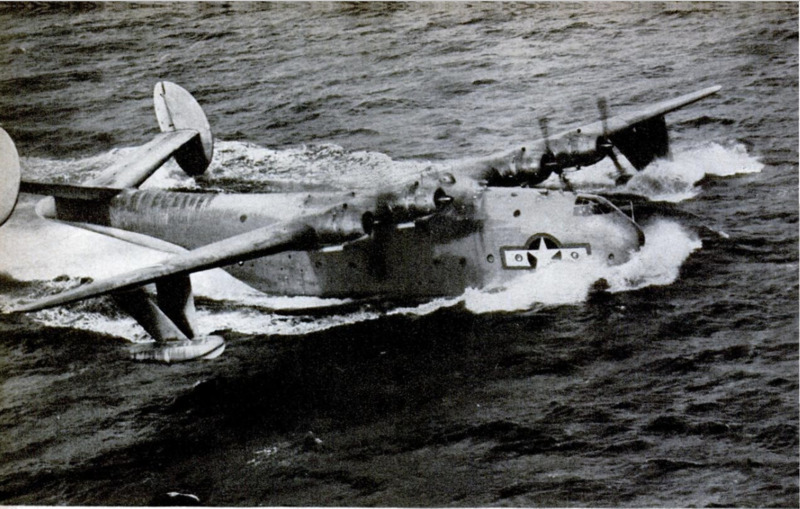

We cruised south over the surface of the

bay with the four big Whirlwinds still warm-

ing. They are of a new type perfected dur-

ing the Mars’ first trials. Then the skipper

brought her about, and we picked up speed

as the nose pointed north. The ship bucked

gently against the waves slapping her bow.

We passengers were snug in the after

compartment, lower deck, behind the last

but one of seven watertight bulkheads that

divide the deck into compartments. High

above us and forward on the flight deck,

Lieutenant Hamilton, the chief engineering

officer, must have pulled all four throttles

wide open. The four engines gave out with

the full roar of more than 9,000 horsepower.

The interphone gave warning: “Stand by

for take-off.”

The starboard ponton lifted clear of the

water. Up in the cockpit Skipper Coney

was trying her for balance. Spray blanketed

our portholes. The wings waggled once as

we lifted into a quartering wind, then all

feeling of motion ceased. There was only

the roar and vibration of the engines. The

take-off was perfect. Seasoned flyers were

amazed at the ease With which the big sea

bird took the air.

But, just to remind you that the Mars is

a big ship, that take-off run was a mile and

a half long. And, just to remind those of

us aboard that she was a new ship with

her reputation still to make, a regular Navy

seaplane tailed us all the way across—

just in case.

‘The sun had dipped behind the Golden

Gate before we left the water, but at 5,000

feet we saw it again. At that altitude—

though the skipper is firm about keeping his

ship in perfect balance—we could shuck our

life jackets and begin to move about the

ship by twos and fours.

Because of her sheer, overpowering size

and the uncanny steadiness of her flight, it's

hard to remember at times that the Mars

is not a ship but a plane.

As you leave the waist compartment and

move forward along the main passageway of

the lower deck, you enter the galley through

a watertight bulkhead. Another bulkhead,

and then a bunk room. Forward of that is

the main cargo hold with five tons of

precious war material lashed tight on either

side of the passageway. Then the fueling

compartment, from which lines lead to the

fuel tanks under the lower deck. Together

the tanks have room for as much high-

octane gasoline as a fully loaded tank car.

Forward of the fueling room is another

bunk room. To port is a fully equipped

‘washroom and shower; to starboard, a ladder

that leads to the flight deck above. Up in

the nose, under the flight deck, are well-

appointed quarters for the officers.

‘The Mars has an interesting history—and

shows it. Her keel was laid at Baltimore

before Pearl Harbor, but she had been

planned originally as a long-range bomber.

With a theoretical range of 8,000 miles, she

might have been able to take off from

Hawai, drop 20 tons of bombs on Tokyo,

and return to Pearl Harbor, but the lessons

of blitzkrieg taught that a bomber has to

be something besides a big truck.

The Mars is not a particularly fast ship;

she hasn't nearly the speed of one of the

newest Fortresses. So the big bomb bays

in her wings were changed into cargo holds.

Next, the Navy had her marked for person-

nel transport. Finally, she proved perfect

as a heavy freighter with room for plenty of

passengers in addition to cargo. Today she

carries no armament, but the machine-gun

blister out in her tail is a reminder that she

has been a flying laboratory for the lessons

of modern war.

As a result of that history of trial and

error, more ships of the Mars type will

soon be coming from the production line. A

score of them will eventually join the Navy's

NATS squadrons—the force that rushes

Navy men and vital material out to the

battle fronts far from home.

You can go up inside the wings, where

the bomb bays were to have been. You

climb a gangway in the waist compartment.

Upstairs you find yourself in a bunk room.

In a second bunk room forward is a short

flight of stairs. At the top, you open a

bulkhead and ease yourself gingerly inside,

above the fuselage. You can stand without

stooping inside the wing. Once each hour

one of the 15 crew members climbs up here;

makes his way among the tubular internal

braces of the wing; inspects engines and

fuel, oil, and ignition lines; looks over the

hydraulic pressure lines that operate the

“booster” on the automatic controls.

The more you see of her, the more the

size of old “Moby Dick” impresses you.

You keep comparing the size of things with

that of the equipment of ordinary planes.

Every so often you have to stop and remind

yourself that the big winged whale is really

purring along over the Pacific, cruising at

between 8,000 and 9,000 feet, smooth as a

Buick rolling over asphalt, quiet as an aver-

age “stateside” airliner, though only parts

of the ship are soundproofed.

Somewhere out over the Pacific, Lt. Ken

Winsor, the third pilot, drops down to the

waist compartment for a smoke.

“Anybody here seen my flight jacket?”

he asks. Passengers and crewmen shake

their heads. “See this.” He takes off his

knitted scarf. “I just found this after a

month.” Yes, you can lose your stuff on a

ship as big as the Mars.

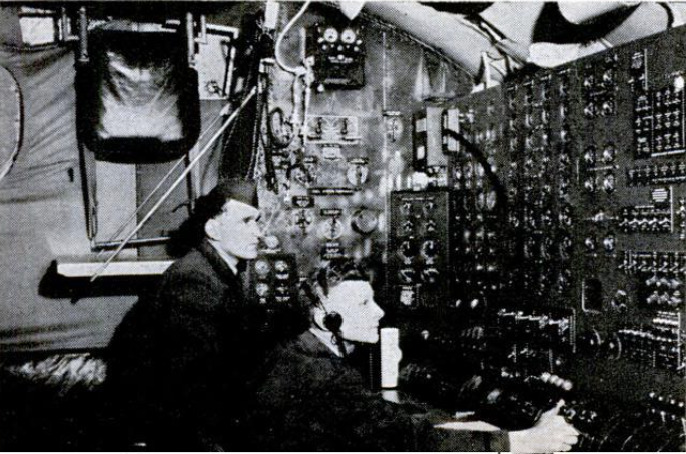

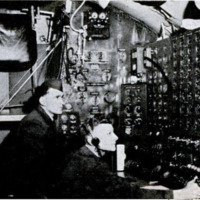

It's up on the flight deck that the really

important work goes on. With plenty of

headroom, it’s as big as an average living

room. As you step off the ladder, the engi-

neer on duty sits at your left with his back

to you, facing two panels loaded with about

150 dials and controls. Up ahead of him, the

two navigators work over their charts and

data spread over a table seven feet long

by three wide. Still farther forward is a

small work table for the flight engineer, and

over to the right sits the radioman. Because

the lights burn all night on the flight deck,

a black curtain separates it from the cock-

pit up In the nose. Aft is a turret not un-

like the top turret on a bomber, where the

navigator can get a fix on a star in any

direction. Standing up there, you feel you

have never been so close to the stars. Be-

sides those stars, only the tail light, the

violet flame pouring from the exhaust ports,

and the red-hot exhaust manifolds remind

you where you are.

Some of us expected excitement on the

Mars’ first Pacific flight. We were disap-

pointed. The ride was as smooth as velvet.

Even when we went up to 9,500 to ride over

the top of a storm, there were hardly enough

bumps to remind us that we were in an

airplane. The Mars, say all three of her

veteran pilots, handles more easily than

any other plane they ever flew. They boast

that she can climb with a full load on any

two of her engines, and she can land with

all of them cut out.

Incidentally, Bill Coney is a former flight

captain for Eastern Alrlines, and his two

copilots on the Mars flew with him in com-

mercial airline work.

This was the skipper's first flight to

Hawaii, and he wanted to set the Mars down

in daylight. She's the first of her kind, far

too valuable to take chances with. In many

ways, she's still a flying laboratory piling

up valuable data.

Though nothing was visible of blacked-

out Hawaii below, the line on the big chart

showed we had nearly reached the island of

Molokai. Navigator Witherspoon and the

skipper bent over the big chart-table. Unless

we were to land in darkness, we had nearly

two hours of flying time to kill, so we turned

right on a dog-leg north of Molokai and just

idled along for three quarters of an hour or

so. When we turned south again, the South-

ern Cross hung low in the sky over Molokai

—an auspicious welcome to Hawaii.

We flew in close to Oahu and circled.

Then, dropping altitude without a quiver, we

swung around Diamond Head and slid into

Honolulu Harbor just as the sun was rising.

“Stand by for landing!”

This time we didn’t bother to put on life

jackets. As far as we were concerned, old

“Moby Dick” had made good. With never

a bump, we landed on the glassy surface

and taxied up to our berth.

The navigator’s clock showed 7:42. Chas-

ing the sun, we'd gained 21; hours on the

clock, and our flying time for the trip was

15 hours nine minutes. We knew that with

equally good weather Bill would make it

next time in about 13.

Out here in Hawaii they stop you in the

street to ask questions when they learn you

came over in the Mars. Hawaii is aching to

know all that military secrecy will permit

to be known about the planes that speed

passengers and cargo across the vast

reaches of the Pacific.

Today, Hawaii teems with uniforms. She

is the great advance base in our island-to-

island campaign as it gathers strength to

drive the Japs from the South Pacific and

back upon the Land of the Rising Sun.

Pearl Harbor and Hickam Field are among

the greatest air bases in the world. A never-

ending line of planes and ships cuts across

the 2,400 miles that separate these islands

from the mainland, and from these islands

other lines stretch out like fingers to every

point where American troops are fighting

in the Pacific. When peace comes, Hawaii

will again be what she used to be—the

crossroads of commercial traffic between

us and the Orient.

Hawaii knows that flying is here for all

time. The war has made this island people

intensely air-minded. Steamship companies

are already planning to supplement their

service with fast air lines. They speak of

bringing passengers from the mainland here

by air for as little as $125, and Hawaiians

are intent on learning what kind of ships

will be landing here in those days to come.

Some believe they will be big land planes

like the Douglas C-54, or big, fast ships like

the Liberator, which can span the distance

to the mainland in nine hours. But many

feel they will be giant sea birds like the

Mars. They point out that the big land

transports must carry four or more tons of

landing gear not needed on an ocean hop,

that they are voracious gas-eaters; that

they require tremendous, deep-laid runways

on which to land with a full load, while the

big flying boats can land on any good-

sized lagoon—of which there are many not

only in these islands but all through the

South Pacific.

Not very fast, but roomy and comfort-

able, able to carry far more weight than

any other plane yet seen, ships like the Mars

may be our luxury airliners for transocean

travel after the war.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Alfred H. Sinks (article writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1944-04

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

82-84, 204, 208

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public Domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Lorenzo Chinellato

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

-

Spatial Coverage (Dublin Core)

-

Hawaii

Popular Science Monthly, v. 144, n. 4, 1944

Popular Science Monthly, v. 144, n. 4, 1944