-

Titolo

-

How to read aerial photos

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Title: How to read aerial photos

-

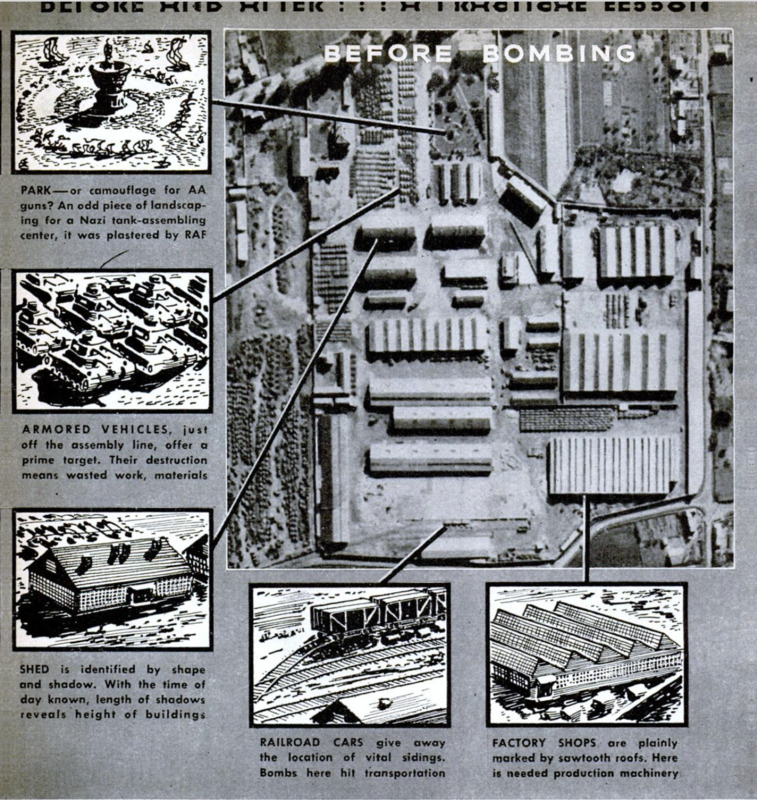

Subtitle: Reconnaissance shots yield telltale clues to trained eyes.

Try your own skill at it after reading this

-

extracted text

-

Ts a layman, many an aerial photograph

of a bombing objective resembles an ama- |

teur cameraman’s first attempt—and an un-

fortunate one at that. Looking at the same

reconnaissance picture, an Air Intelligence |

expert sees trenches, machine guns, houses, |

factories, railroads, and highways. |

Likewise, after bombers have done their

work, new photographs often fail to show

impressive evidence of destruction to the

layman's eyes. But the art of the trained

photo interpreter reveals telltale signs of

war plants knocked out of production, of

ruined airport runways, and of crippled rail

centers. |

An amateur can easily learn at least the |

ABC's of reading aerial photographs—a fas-

cinating detective game of making shrewd

deductions from simple clues. While some

of the methods that professionals use must

remain strict military secrets, enough can

be told here to make pictures from the air |

far more intelligible to a novice.

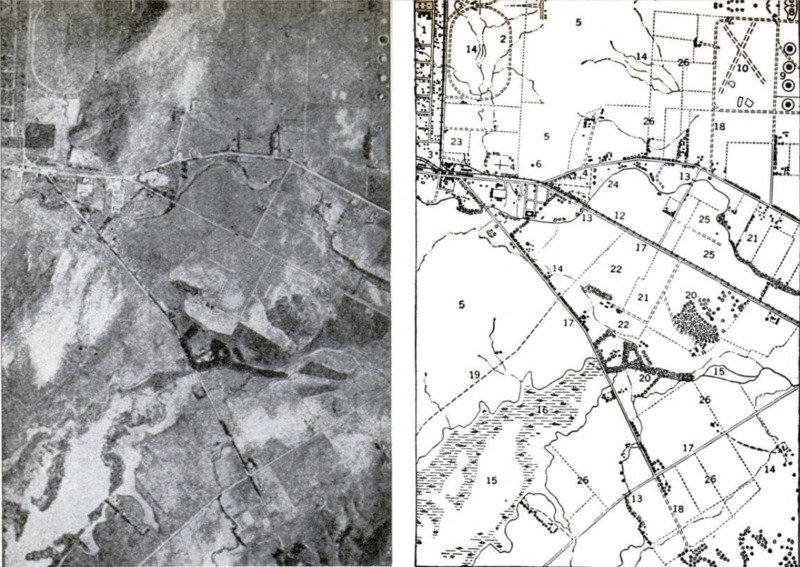

Any city, town, or countryside may pro-

vide landmarks to guide raiders, or may take

on military importance in a land campaign.

Suppose, therefore, we start with a strate-

gical background of familiar landscape fea- |

tures. Of course they will look strange from

the air, because we are accustomed to see-

ing them sideways and not from overhead.

To identify an object, the most important

aids include its shape, its lightness or dark-

ness, its shadow, and its size.

‘When a long, straight line crosses an

aerial photo, you need not look for locomo-

tives or cars to arrive at the conclusion that

it is a railway. If it does have curves, they

will be gradual, in accordance with stand-

ard railroading practice. Conversely, a series

of straight lines joined by sharp curves must

be a motor highway. Simple, isn't it?

It may take more imagination to decide

what to make of a chevron-shaped swath |

cut through a forest. A person experienced |

in looking at air views will recognize it as a |

clearing for a high-tension electric trans- |

mission line. Once you are in on the secret, |

the simplest geometry points to the tower

where the wires change direction. Because

of their way of marching across country

with little regard for topography, high- |

tension wires are easily recognized. |

Perhaps you will puzzle at first over one

of the most easily identified features of an |

air view—a pattern of black dots neatly ar-

ranged in rows and columns. It is an or-

chard, and the dots are the trees.

Natural features of a landscape readily

distinguish themselves from the regular pat-

terns of man-made objects. The wandering

course of a stream, for example, could hard-

ly be mistaken for anything else.

Gradations from white to black, called

tone or texture, tell a story of their own.

Roads, which reflect light well, show up in

light tones—the more heavily traveled, the

lighter. Plowed fields, too, are good reflec-

tors. Meadows look darker because of shad-

ows cast by the grass, just as plush looks

darker than satin of the same color. Woods,

heavily shadowed by trees, appear very dark.

Cultivated fields range through a variety of

intermediate tones of gray, from which an

expert can often determine just what crop

is being grown! A body of smooth water

may show up light or dark, according to the

angle of the sun, whose rays it reflects like

a mirror instead of scattering them like

loose soil.

Face a window or light, and hold an aerial

“photo with its shadows toward you. This

correct way of viewing it prevents hills from

being mistaken for hollows, and craters for

mounds. Besides giving an illusion of relief,

shadows also indicate shape and size. An

oblong object, half bright and half dark,

turns out to be a house with slanting roofs;

one roof slope faces the sun while the other

is in shadow. If you know the time of day

when a picture was taken, the height of a

building may be compared with its length

and width by noting the length of its shad-

ow on the ground.

In scaling the size of objects, comparisons

help. A truck on a road gives an idea of the

road’s width; and the size of a warehouse

may be estimated with respect to a dwelling.

Supplementing each other as they do,

these clues lead to further deductions. A

likely place to look for a bridge is a narrow

part of a river. A picture shows a well-trav-

eled highway leading to such a point. Closer

examination reveals the bridge itself —which

looks lighter than the water, and further

reveals itself by its size, shape, and shadow

on the stream. In the art of aerial photo

interpretation, as in chemistry and many

other fields, a skilled analyst has a pretty

good idea of what he is going to find before

he finds it.

Superimposed upon ordinary terrain, mil-

itary works reveal themselves to the eye of

the flying camera. Trenches, reappearing in

the present war, stand out by virtue of their

zigzag pattern, or that of the earth dug out

to make them. ‘Foxholes” can usually be

picked out by their sharp outlines and deep

shadows. Wire entanglements show up as

broad lines or ribbons—accentuated, if new-

ly laid, by the tracks of working parties.

Similar tracks betray frequently visited

machine-gun positions. Grass trampled by

soldiers may be clearly distinguished from

other growth. Any disturbance of nature's

patterns is a sure sign of human activity.

Neither telephone posts, their shadows, nor

wires can usually be seen in reconnaissance

photos—but the earth removed to sink the

poles, and the trails left by construction

crews, make a series of small, regularly

spaced dots connected by a thin line. As

might be expected, a photo interpreter with

tactical training benefits by knowledge of

how he would dispose his own troops, guns,

and headquarters in a similar situation.

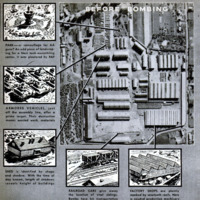

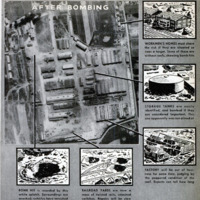

Permanent tar-

gets such as railroad yards, oil tanks, and

canal locks are virtually impossible to con-

ceal from aerial cameramen. Locations of

chemical works, arms factories, pipe lines,

and other objectives are known to industri-

alists all over the world, and picking them

out on reconnaissance photos offers little

difficulty. Even when they may be shifted

from place to place, the secret is hard to

keep. From much-bombed Bremen, the

great Focke-Wulf airplane assembly plant

was moved to Marienburg in East Prussia,

farther than Allied bombers had ever pene-

trated into Germany. Just the day before

Reichsmarshal Hermann Goering was to

dedicate one of its new buildings, the U. S.

Army's Eighth Air Force spared him the

trouble by razing the whole Marienburg

plant to the ground. In this case, one of the

clearest air photos ever taken leaves no

doubt of the havoc wrought by precision

bombing.

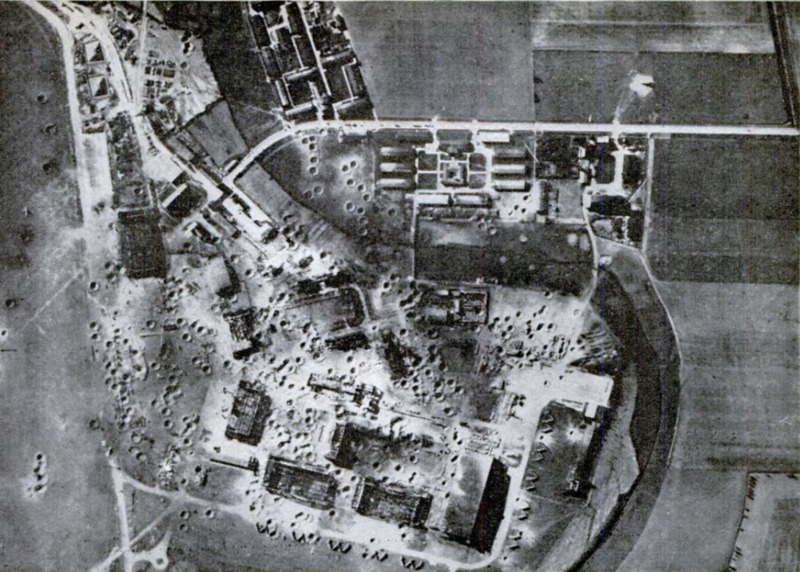

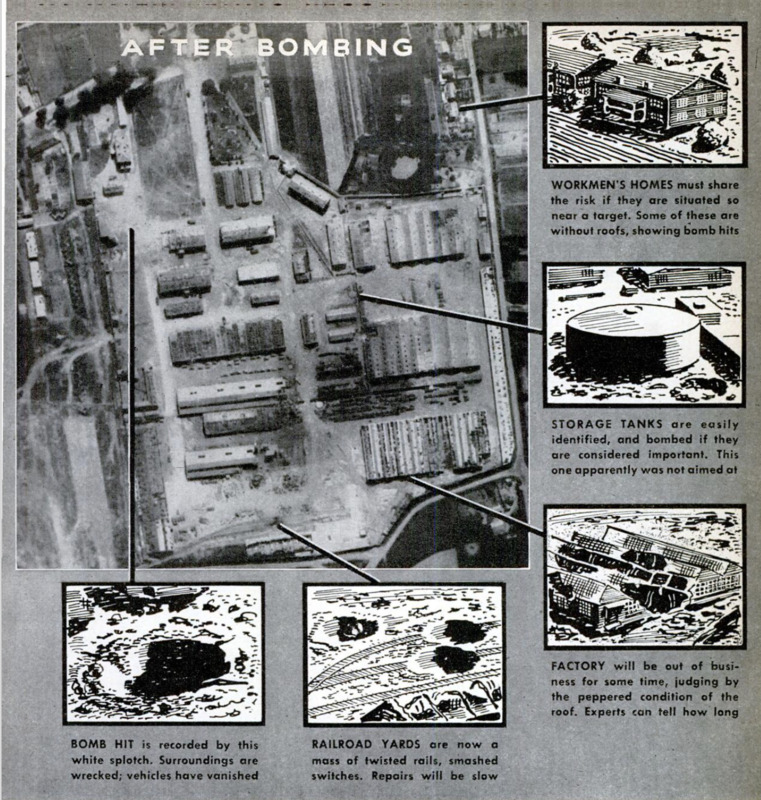

Less conspicuous clues often reveal the ex-

tent of destruction. A factory with a chunk

missing or with gaps in its roof probably

has suffered heavy damage from a near-by

hit and flying debris. Shapes like open

boxes are the shells of bombed-out buildings.

Tops of walls still standing appear white,

because the crumbled surfaces reflect sun-

light. A checkerboard pattern of bright

spots in the shadow of a wall indicates sun-

light streaming through the window spaces

of an unroofed structure. An indistinct,

blackened heap vaguely resembling the out-

line of a building signifies a ruin gutted by

fire. A white splotch, practically free of

shadows, shows where a bomb hit; and

signs of damage will radiate from it. If the

white scar is more or less oblong, a whole

building has been blasted from its site.

By comparing “before-and-after” pictures

of bombing, some of which are reproduced

here, a beginner quickly gets the idea. And

a professional photo interpreter, aided by

industrial technicians and statisticians, can

estimate with remarkable accuracy the

daily loss to the enemy in gasoline or ball

bearings; the percentage of his total re-

sources that this figure represents; and the

time that it will take to get any reparable

plants back into production.

Latest refinements of aerial photography

—notably, improved natural-color and relief

processes—come to his aid. New color film

permits views to be taken from planes speed-

ing faster, or in less favorable light, than

ever before. Their realistic hues unmask en-

emy attempts at camouflage that might go

unnoticed in black-and-white photography.

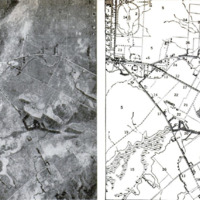

Relief views, which show objects in three

dimensions, take the flatness out of aerial

pictures. Here is an ordinary aerial photo-

graph of what looks like a smooth beach,

suitable for an invasion landing. A relief

picture shows, instead, a high cliff from

which a few gunners could mow down any

would-be invaders. Probably, signs of relief

in the flat picture—such details as stream

courses—would prevent a photo interpreter

from being misled, but a quick glance at

the other view saves time and effort. |

As for the man who makes the pictures,

it need not be supposed for a moment that

enemy forces look on complacently while

he photographs their installations. At all

costs, their object is to prevent him from

getting back to his base with the views.

Therefore, it is easy to imagine the frus-

trated wrath of a group of American air-

men in India. At regular intervals, a Japa-

nese airman, whom they nicknamed “Photo

Joe,” paid them visits. Between clicks of

his shutter, he radioed insults in perfect

English, confident that they had no plane

capable of reaching his high altitude in time

to catch him. Then the Yanks stripped a

P-40 of everything but guns and climbing

performance. Right on schedule, “Photo

Joe” reappeared with his taunts—just once

too often.

Fortune gave a different twist to a Euro-

pean incident when an American pilot, at

the completion of a photographic mission,

found an Axis fighter plane closing in on

either side of him. Just at the moment their

guns spat fire, he climbed sharply. While

his enemies shot each other down, he made

good his escape!

Freak engagements like this may be rare,

but daring exploits of flying cameramen

are legion. For there is military information

of inestimable value in the pictures they

bring back—if you know how to find it.

-

Autore secondario

-

Alden P. Armagnac (article writer)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1944-04

-

pagine

-

123-126, 199

-

Diritti

-

Public Domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by

-

Lorenzo Chinellato

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)