-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

Allied invasion fleet consists of thousands Landing craft, ranging from rubber boats to transocean tank carriers

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

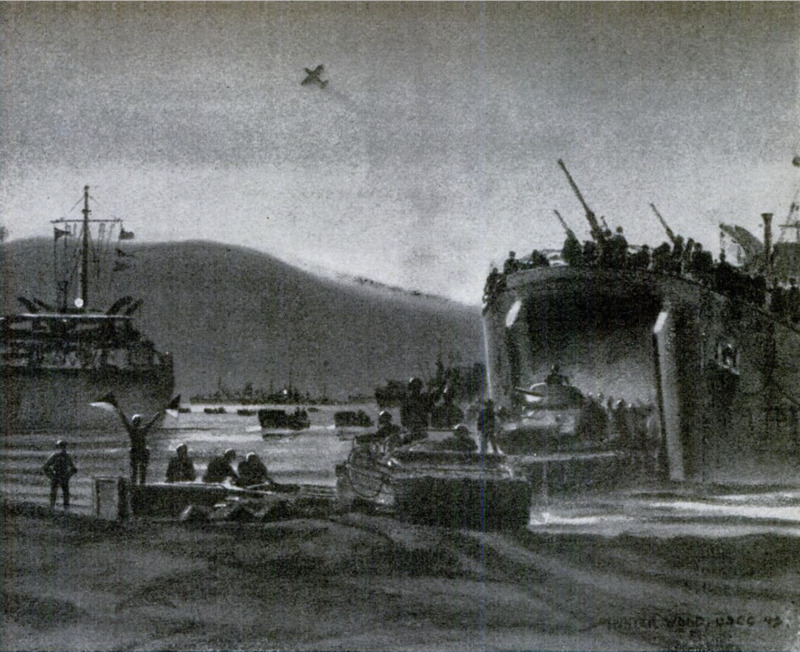

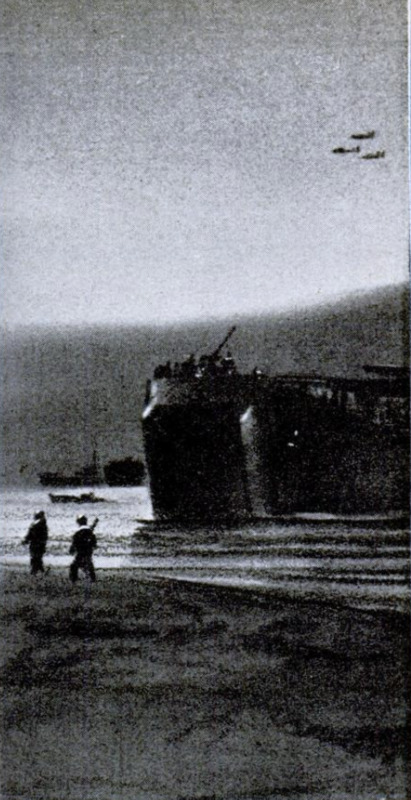

Title: How we built our invasion fleet to storm enemy shores

-

Subtitle: A $1,000,000,000 armada of thousands of landing craft, ranging from rubber boats to transocean tank carriers, forms the flotillas of victory

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

HE building for our Navy in less than

ie years of a billion-dollar armada of

over 25,000 landing craft of unprecedented

design, ranging from 16-foot rubber boats

to 4,000-ton ocean-crossing tank carriers,

ranks high among all-time naval construc-

tion achievements. During the same period,

additional thousands of these highly special-

ized ships and smaller craft were produced

in America for our British allies. Today

they are being turned out even faster by

shipyards and boat-building and industrial

plants in 27 states, and a considerable por-

tion of the five billions recently appropriated

by Congress for naval auxiliaries will be

spent for them.

These “invasion boats” are our go-getters

of victory. They have made possible our

successful landings in North Africa, Sicily,

and Italy and on numerous Pacific islands.

They are a vital factor in the United Na-

tions’ military plans for the near future.

Used in conjunction with our sea and air

power, they provide the means of landing

troops and their mechanized equipment

quick reinforcement of the troops first

ashore was made impossible by the slowness

of the boats and by the small numbers of

soldiers the boats could carry. If piers

weren't available—and they usually weren't

—they had to be built under fire before any

but the lightest of field guns could be got

ashore.

Napoleon was the originator of specialized

invasion craft. In 1804, in preparation for

the conquest of England, he built hundreds

of shallow-draft rowing and sailing boats

and barges designed for the sole purpose of

carrying his army from Boulogne across 26

miles of salt water and landing it on English

beaches. Cornerstone of his plan was the

bottling up of the English fleet in the

Channel, while the landing was in progress,

by the combined French and Spanish fleets

holding the Strait of Dover. But the British

fleet maintained uninterrupted control of

the sea, and Napoleon had to leave his in-

vasion craft to rot on the Boulogne mud flats.

Leaders of amphibious expeditions went

on putting their troops ashore in ships’

boats. That still was the accepted method

of making opposed landings when we in-

vaded Cuba in 1898, although by then the

boats usually were towed by steam launches.

Lack of suitable landing craft forced us to

drop our cavalry and artillery horses over-

board with the hope that they would be able

to swim to shore, and the loss by drowning

of seven percent of these essential animals

set European general staffs to thinking

about specialized landing boats. By 1913

the Russians were using 40-foot collapsible

steel barges capable of transporting either

a heavy field gun or 200 soldiers, the British

were experimenting with folding wooden

boats which carried 50 men, and the Ger-

mans were trying out both types.

Early in World War No. 1 the British

attempted to capture the Gallipoli Peninsula

for the purpose of opening the Dardanelles.

In April 1915, British and Anzac troops were

landed from transports in ships’ boats and a

miscellaneous assortment of small craft

picked up in Mediterranean ports. The

terrible losses in-

flicted on the troops by the Turkish machine

guns convinced the British General Staff

that specialized landing craft were essential

for such operations. A result of thid costly

lesson was the building of shallow-draft

barges propelled by gasoline engines, pro-

vided with bow ramps which made quick

disembarkation possible, and capable of

carrying about 500 infantrymen. These

“X Lighters,” used successfully in the land-

ing at Suvla Bay in August 1915, were the

first self-propelled landing craft.

Considerable experimental and develop-

ment work on landing craft was done be-

tween the two world wars. The Japanese

used some self-propelled landing barges

early in their Chinese operations, and in

1938 used 50-foot troop-carrying barges

driven by airplane propellers in their ascent

of the shallow Yangtze River. The British

designed several types of landing craft, but

apparently built only a few experimental

models before the outbreak of the present

war. The Germans produced quantities of

rubber boats and rafts, which proved highly

effective in river crossings; how far they

progressed with craft designed to land

troops and their mechanized equipment on

ocean beaches is not known.

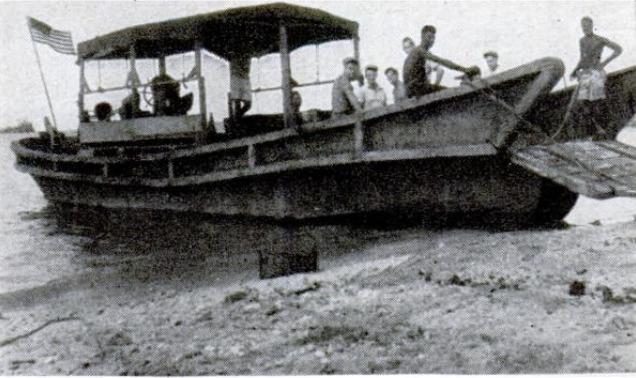

When, in 1935, our Navy became interested

in troop-landing barges to be carried in the

boat davits of transports, a New Orleans

builder of motor work boats had developed

a craft which, in its essentials, was just

what was needed. Andrew Jackson Higgins

had been building —and improving — his

“Eureka” boats for 20 years. Originally de-

signed to meet the needs of the fur trappers

of the southern Louisiana bayous, they were

being used in large numbers by Louisiana

oil drillers and by Central American oil and

plantation companies. They could operate

in very shallow water, carry heavy loads,

and withstand almost unlimited hard usage.

Their spoon bows enabled them to slide over

sand bars and drift logs and land almost

anywhere. And they were fast; a number

of years ago a Higgins boat established the

still-standing record of 72 hours for the

1,150-mile Mississippi River run from New

Orleans to St. Louis.

After a lengthy period of development,

minor design alterations, and testing, the

Navy adopted a 26-foot-long, 10%-foot

beam, Diesel-engine-powered modification

of the Higgins “Eureka” model and gave

it the type designation LCP(L)—Landing

Craft, Personnel (Large). These original

model Higgins boats have been used ex-

tensively in the Pacific, and by British

Commando raiders.

Somewhat later a 36-foot ramp troop-

landing boat produced by another builder

also was adopted, and designated LCPR—

Landing Craft, Personnel, Ramp.

Shortly after Pearl Harbor, offensive

operations being planned for the Pacific

theater made necessary the prompt produc-

tion of a landing craft capable of carrying

a jeep or even a light tank, and of landing

its load quickly. Higgins solved this design

problem by giving his original boat a ramp

bow and a few additional inches of beam.

This type was designated LCV—Landing

Craft, Vehicle.

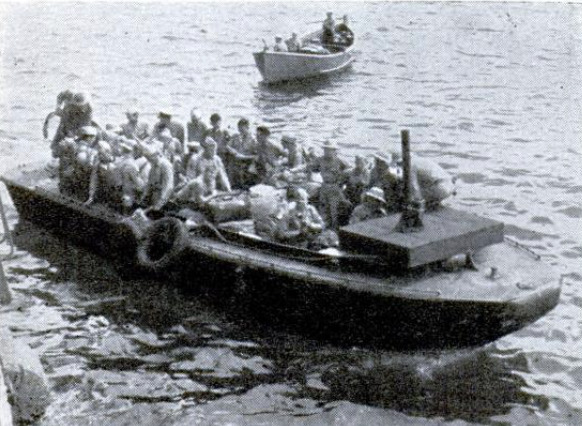

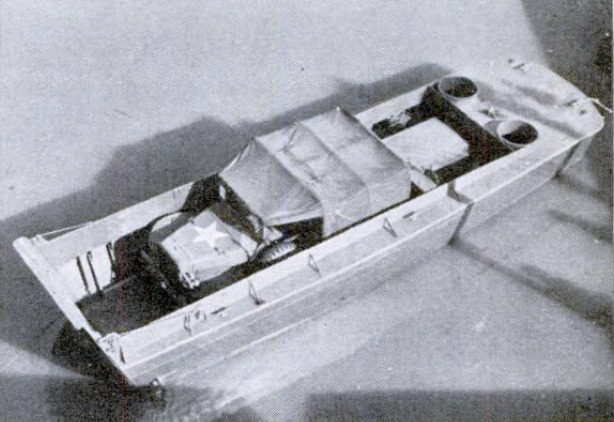

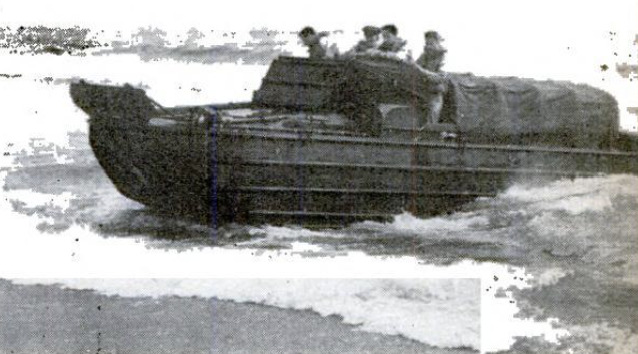

Today's LCVP—Landing Craft, Vehicle,

Personnel—was developed from the earlier

Higgins boats. It is the Navy's standard

“beach climber,” and with the exception of

a rubber boat the only one now being built.

It is 36 feet long, has a beam of almost 11

feet, is armed with two .30 caliber machine

guns, and—like all our landing craft—is

Diesel powered. Operated by a four-man

Navy crew of coxswain, engineer, signal-

man, and bow-hookman who operates the

ramp and doubles as a gunner, it can carry

either 36 fully-equipped infantrymen, a light

howitzer and its crew, or a jeep and its crew.

Built of plywood, with a triple bottom, its

construction and design are protected by a

score of patents.

The Navy placed its first quantity order

for Higgins landing boats in November 1940.

Some months ago Higgins Industries cele-

brated the launching of its seven thousandth

“beach climber.” LCVP's also are being

produced under Higgins patents—given to

the Navy for the duration—by several other

builders in various parts of the country.

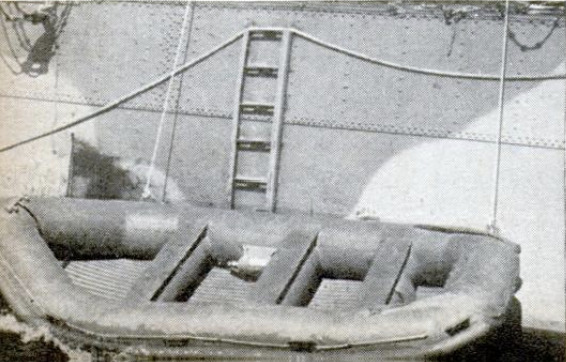

Inflated rubber boats sometimes are used

by the Marines, especially when they “shove

off” on landing missions from small auxiliary

vessels. LCR(L)—Landing Craft, Rubber

(Large)—is the standard type. Made of

heavy rubberized fabric, it weighs about 450

pounds, is 16 feet long and about four feet

wide, and carries 10 men. Most of the boats

of this type are propelled by paddles, but

some of them have extension-shaft outboard

motors hung from wooden brackets strapped

to their sterns.

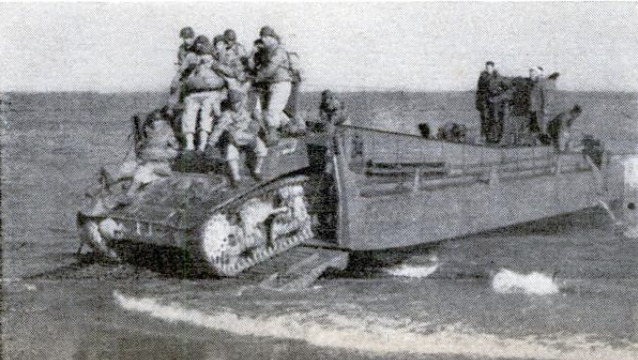

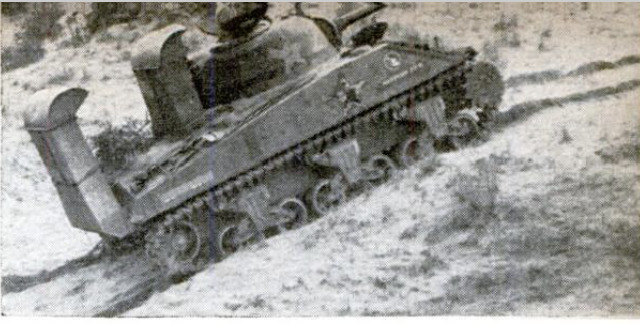

In 1936 the Navy started the develop-

‘ment of tank-landing lighters for the Marine

Corps. After several years of experimenta-

tion the Higgins-designed 45-foot LCM-2—

Landing Craft, Mechanized, Model 2—was

accepted. The first craft of this type was

built in the street back of the Higgins plant

early in 1941, and still is in service in the

Pacific. When it became evident that medium

tanks were going to be vitally important

weapons in this war, the LCM-2 type was

enlarged into the now standard LCM-3,

which is 50 feet long and 14 feet wide.

Built of steel and powered by two Diesel

engines, it carries a medium tank or a

heavy gun or truck, and is so fast and

easily handled that it can be used with the

“beach climbers” in the first assault wave.

Higgins has produced well over 1,000 LCM’s,

and they also are being built under the

Higgins patents by 22 other manu-

facturers.

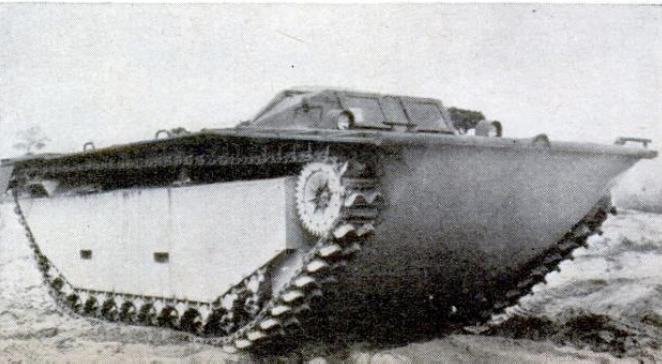

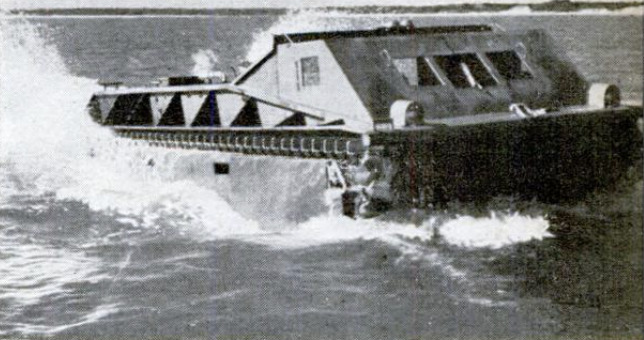

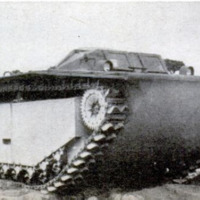

Supplementing the landing boats

are two land-water vehicles which

have proved their value under fire

—the Army’s “duck truck” and a

new amphibious tracked vehicle de-

veloped from the Marines’ Alligator

tank,

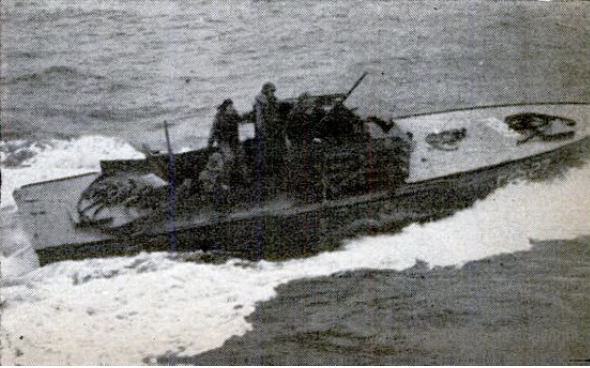

To protect and support the land-

ing-boat flotillas on their perilous

missions the Navy has developed

fighting craft. The LCS—Landing

Craft, Support—has been nick-

named “the seagoing bazooka.” Of

the same spoon-bowed hull design

as the original Higgins LCP(L), it

is formidably armed with rocket

projectors and machine guns, and

has smoke-screen apparatus,

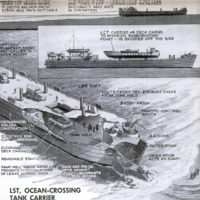

Shortly after the Dunkirk evacuation in

1940, the British, determined some day to

get their army back on the Continent, began

to build landing craft. They developed

several satisfactory types of medium-sized

tank-landing lighters, but experience in

mechanized warfare convinced them that

+ for large-scale invasion operations they also

would need tank carriers of an entirely new

type—powerful and seaworthy ships which

could transport large numbers of medium

or heavy tanks on long ocean voyages, but

which could also be beached so that their

tanks could be landed quickly under their

own power. The original conception of this

unheard-of sort of ship is said to have been

a product of the fertile mind of Winston

Churchill.

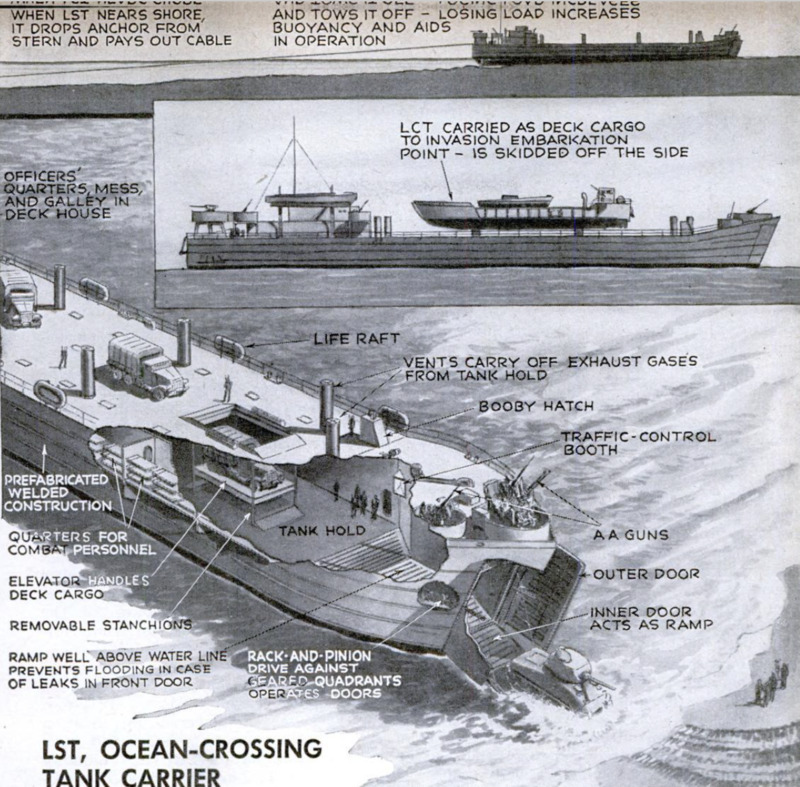

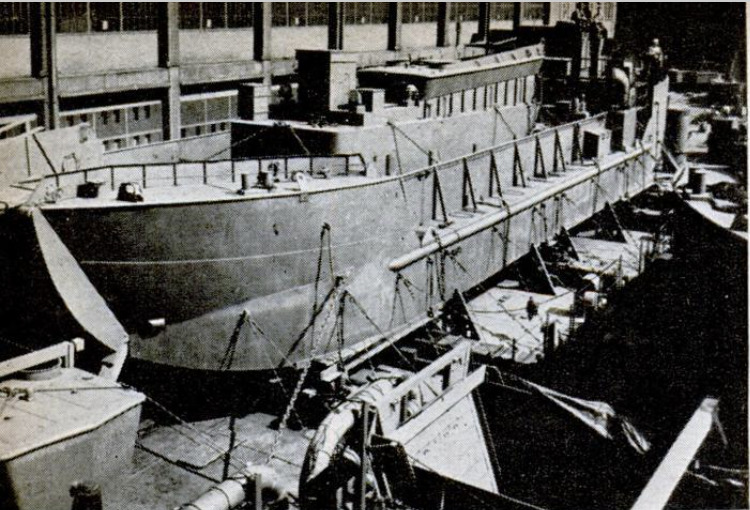

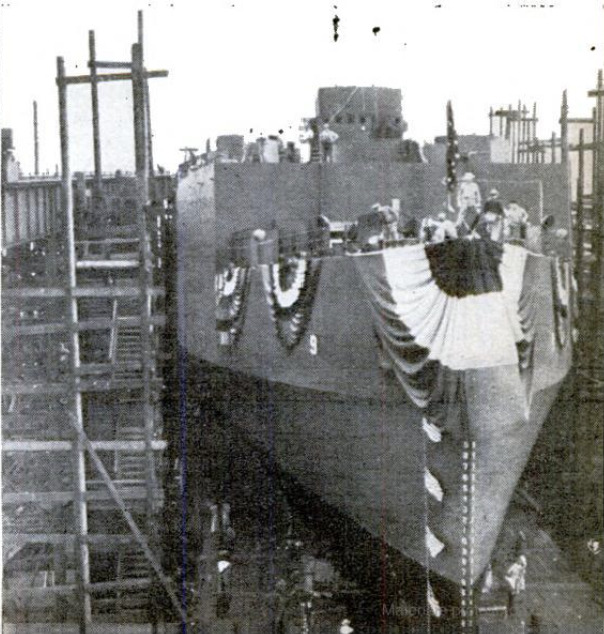

‘When our Lend-Lease law was enacted in

1941, we were asked to undertake the build-

ing of all the larger types of landing craft.

British Navy officers came to Washington

in November and conferred with officers of

our Navy's Bureau of Ships. The result of

their talks was the LST—Landing Ship,

Tank. Twenty months after the design was

sketched, ships of this type had disgorged

their tanks on the beaches of Sicily, Italy,

and various Pacific islands.

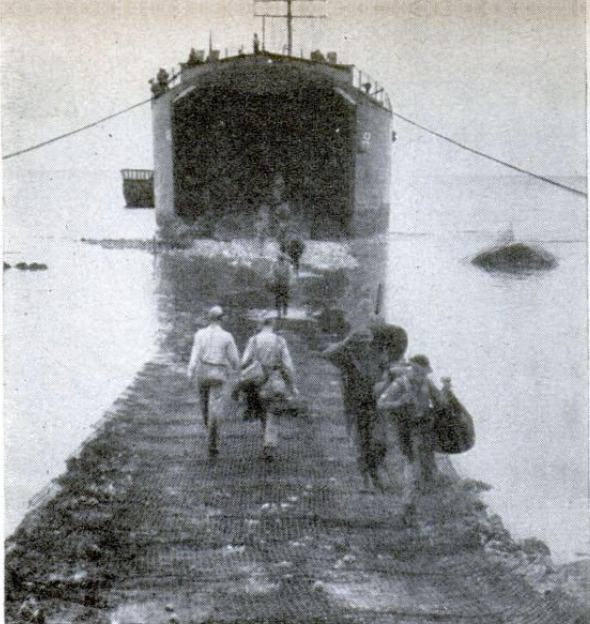

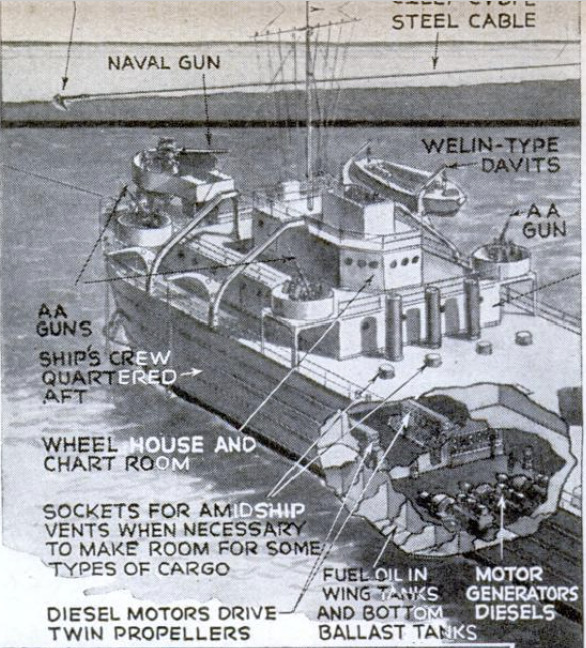

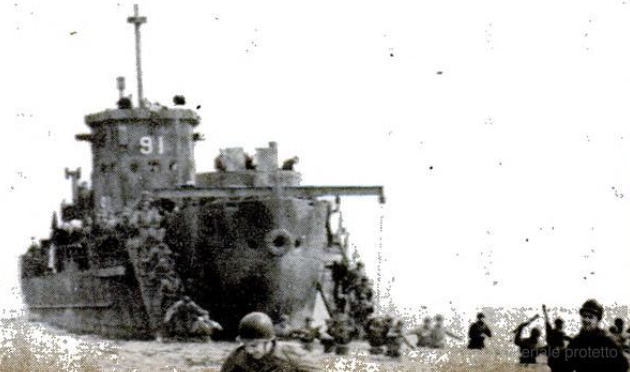

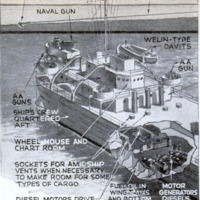

LST’s are husky steel ships well over 300

feet long. Most noticeable of their many

novel features are the ponderous bow doors

which are swung open when the ships are

beached to discharge their tanks. The large

open space in the hull resulting from the

two-deck-high tank deck, which runs far

aft and is kept free from fumes by venti-

lators opening on the upper deck, posed a

difficult structural-design problem which

was solved by extensive compartmentation

of the lower hull. Except that LST’s draw

more water aft than they do forward, nothing

may be said about the underwater hull design

that makes them both seaworthy and capable

of being beached.

Two powerful Diesel engines drive twin

screws; there also are three auxiliary Diesels

which provide power for operating the bow

doors, ramp, and ventilating fans. LST’s

carry a heavy armament of antiaircraft and

dual-purpose guns, and are manned by crews

of eight officers and 85 enlisted men. They

carry large numbers of tanks or other

mechanized weapons, and heavy deck loads

of trucks, smaller landing craft, or other

cargo.

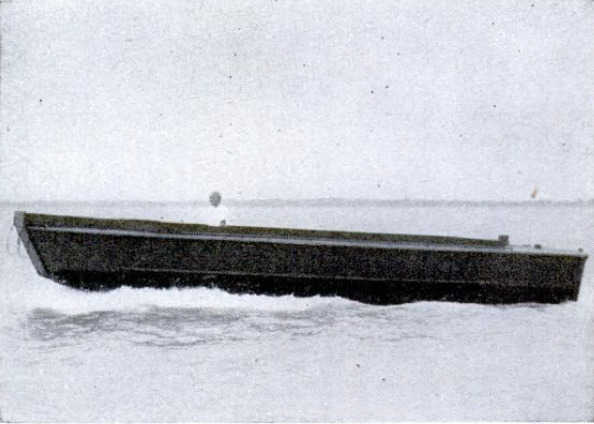

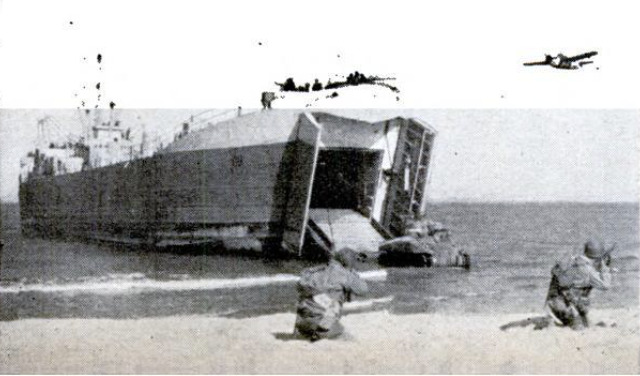

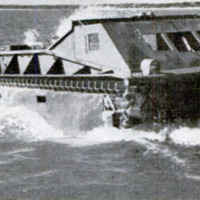

LCT's—Landing Craft, Tank—are Diesel-

powered steel landing lighters developed

. from similar British craft. They are a little

over 100 feet long, are armed with anti-

aircraft guns, and are of such shallow draft

that they can drop their bow ramps and

land their loads of medium tanks or guns,

trucks, or jeeps on even gently sloping

Jbeaches. They are built in three sections, so

that they may be taken apart for long-

distance transportation on LST's or cargo

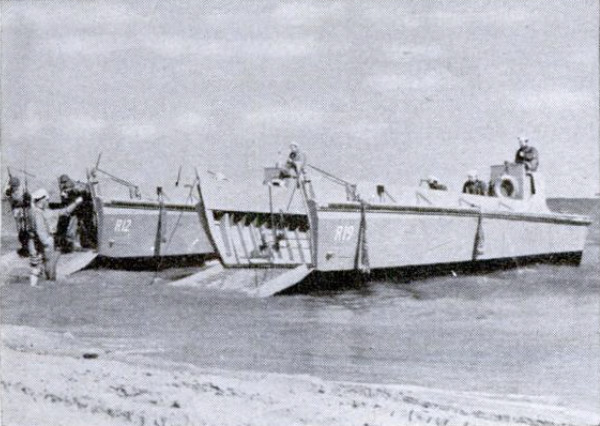

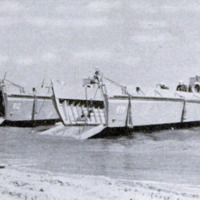

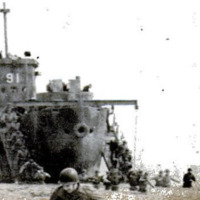

ships.Originally designed by our Navy to meet

British needs, the LCI—Landing Craft, In-

fantry—has become an important vessel of

our invasion armada. It played an important

part in our Sicilian and Kiska operations.

LCI's are over 150 feet long, are as smart-

looking as destroyers, and are seaworthy,

powerful, and heavily armed. Although they

are capable of crossing the Atlantic, they

also can be beached in shallow water, and

land about 200 doughboys by means of twin

ramps which are lowered at either side of

their bows.

‘When the building of the first billion-

dollar section of our invasion armada was

undertaken, all shipyards and most boat-

building plants were working at full ca-

pacity. New sources of production had to

be found, and numerous contracts were

awarded to industrial concerns, located

along inland waterways, which had ex-

perience in steel fabrication but knew

nothing about ship or boat building. Work-

ers had to be trained. But all who had a

part in the big job, down to the newest girl

working for a subcontractor turning out

the smallest part, were told that they were

helping to build “invasion boats.” That was

enough. They got thousands of landing

craft finished in time to make possible our

first land offensives against the Nazis and

the Japs.

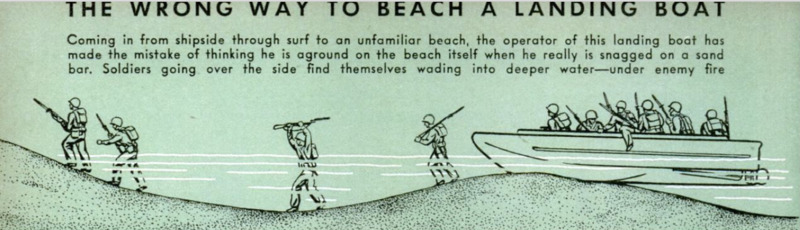

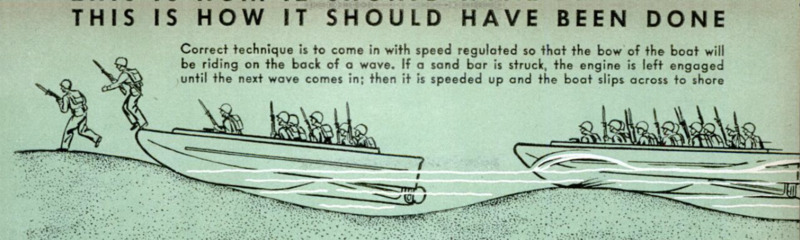

While the boats were being built, the Navy

was training crews to man them. Handling

landing craft, no matter what their size, in

all conditions of weather and surf and

against determined opposition from the

shore, is a job which takes plenty of know-

how and as much courage and physical en-

durance. Many of the sailors now manning

landing boats in active service—a number

of them already have won decorations for

bravery—received their training at the Am-

phibious Training Base near Norfolk, Va.,

or at one of the several other landing-craft

training bases in the Chesapeake Bay area.

These training establishments all are part

of the Atlantic Fleet Amphibious Training

Command of Commodore Lee P. Johnson.

So is Camp Bradford, also near Norfolk,

where troops ready for overseas service are

given a brief and strenuous course in in-

vasion techniques.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Arthur Grahame (article writer)

-

Hunter Wood (illustrator)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1944-04

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

72-79, 200

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public Domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Lorenzo Chinellato

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Popular Science Monthly, v. 144, n. 4, 1944

Popular Science Monthly, v. 144, n. 4, 1944

Immagine 2022-05-02 203845.png

Immagine 2022-05-02 203845.png Immagine 2022-05-02 203828.png

Immagine 2022-05-02 203828.png Immagine 2022-05-02 203859.png

Immagine 2022-05-02 203859.png Immagine 2022-05-02 203911.png

Immagine 2022-05-02 203911.png Immagine 2022-05-02 203926.png

Immagine 2022-05-02 203926.png Immagine 2022-05-02 203939.png

Immagine 2022-05-02 203939.png Immagine 2022-05-02 203950.png

Immagine 2022-05-02 203950.png Immagine 2022-05-02 204004.png

Immagine 2022-05-02 204004.png Immagine 2022-05-02 204017.png

Immagine 2022-05-02 204017.png Immagine 2022-05-02 204026.png

Immagine 2022-05-02 204026.png Immagine 2022-05-02 204042.png

Immagine 2022-05-02 204042.png Immagine 2022-05-02 204057.png

Immagine 2022-05-02 204057.png Immagine 2022-05-02 204106.png

Immagine 2022-05-02 204106.png Immagine 2022-05-02 204118.png

Immagine 2022-05-02 204118.png Immagine 2022-05-02 204132.png

Immagine 2022-05-02 204132.png Immagine 2022-05-02 204142.png

Immagine 2022-05-02 204142.png Immagine 2022-05-02 204153.png

Immagine 2022-05-02 204153.png Immagine 2022-05-02 204204.png

Immagine 2022-05-02 204204.png Immagine 2022-05-02 204220.png

Immagine 2022-05-02 204220.png Immagine 2022-05-02 204231.png

Immagine 2022-05-02 204231.png Immagine 2022-05-02 204243.png

Immagine 2022-05-02 204243.png Immagine 2022-05-02 204257.png

Immagine 2022-05-02 204257.png Immagine 2022-05-02 204306.png

Immagine 2022-05-02 204306.png Immagine 2022-05-02 204317.png

Immagine 2022-05-02 204317.png Immagine 2022-05-02 204331.png

Immagine 2022-05-02 204331.png Immagine 2022-05-02 204345.png

Immagine 2022-05-02 204345.png