-

Titolo

-

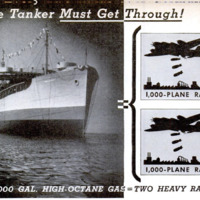

Floating Fuel Tanks Keep the Bomber Flying

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Floating Fuel Tanks Keep the Bomber Flying. How shipyards turn out the vessels that feed our air armadas

-

extracted text

-

WITH men and steel and imagination,

U. S. shipbuilders fight to overcome

our No. 1 war handicap—two wide oceans

to cross. They've already given us a mer-

chant fleet nearly three times its prewar

size. But that’s not big enough. They must

build faster and faster, lest front lines over-

seas falter and fail for want of food, fuel,

and reinforcements.

In the surging drama of our shipbuilding

program, all vessels assume importance.

Each one has her role in literally carrying

the battle to the Axis. Every new ship, from

the great gray troop carrier to the lowliest

seagoing craft, adds to our combat strength.

We dare not underestimate the contribution

of a single one. But a thick slice of glory

must go to the tanker—that world-girdling

fuel packer—without which our thunder-

ing air armadas would sputter and die.

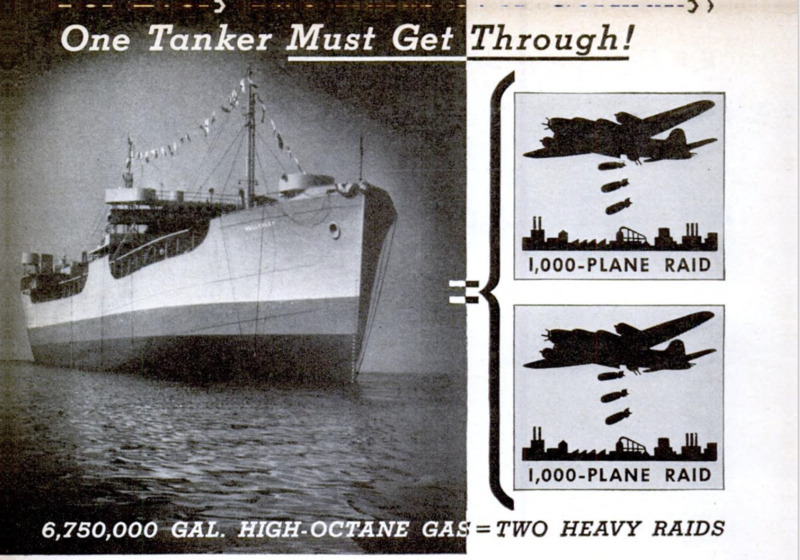

When our Flying Fortresses and Liber-

ators zoom off on one of their devastating

1,000-plane raids on the Reich, they lug

enough gasoline to keep the average Amer-

ican motor car running for 1,000 years.

Each plane has to carry around 3,000 gal-

lons to get to the target and back to Britain.

But—you've guessed it! Some unsung tank-

er has braved an Atlantic crossing to supply

that fuel. And one big raid uses up half its

entire load.

‘With an air force of tens of thousands of

fighters, in addition to giant bombers, de-

livery of fuel to keep 'em flying moves to

the front rank of war problems. Add to

that the healthy thirst of an even greater

number of motor vehicles in our mechanized

columns, which also must strike at the

enemy from foreign soil, and you begin to

realize why the U. S. Maritime Commission

and our War Shipping Administration place

such warm bless-

ings on every new tanker that is launched.

It was on a blustering, rain-drenched day

that a writer and photographer of POPULAR

SCIENCE MONTHLY received admission to

the Bethlehem Steel Company's Sparrows

Point shipyard. Cold wind whistled through

towering works surrounding tankers under

construction on the waterfront near Balti-

more, Md. Rain beat in our faces. It was a

fine day to sit at home by the fire. But that

thought didn't seem to occur to Manager

Frank A. Hodge and his thousands of busy

workers. Their chief concern, we learned,

had nothing to do with meteorology. It cen-

tered on their unfinished ships—ships des-

tined to be completed on or before schedule

~regardless.

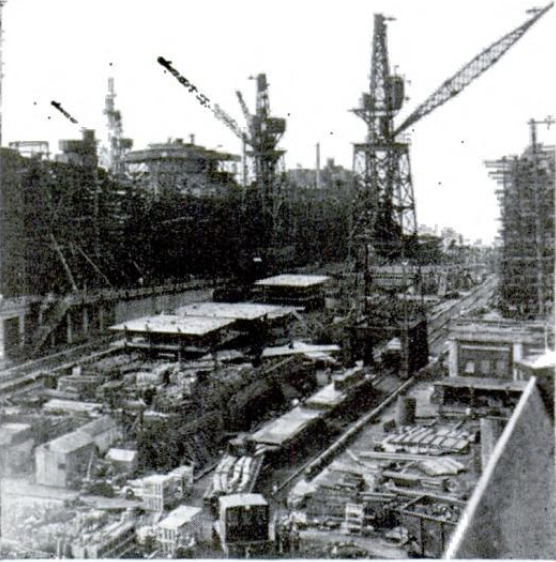

Sparrows Point, we learned, has heen

keeping shipbuilding schedules since 1889.

It built craft used in our last two wars,

and it's well represented in this one. From

its sloping ways on the sprawling Patapsco

River has come as wide a variety of ships

as you can imagine—sidewheel and packet

steamers, coastal liners, tugs, colliers, tor-

pedo boats, and tankers. Unlike yards build-

ing the Liberty ships and other one-design

craft, “the Point” turns out “tailor-made”

ships— vessels of special design to fill the

special needs of a nation whose battle fronts

thrust onward across the seas. It's prepared

to construct as many as six different types

of ships at the same time.

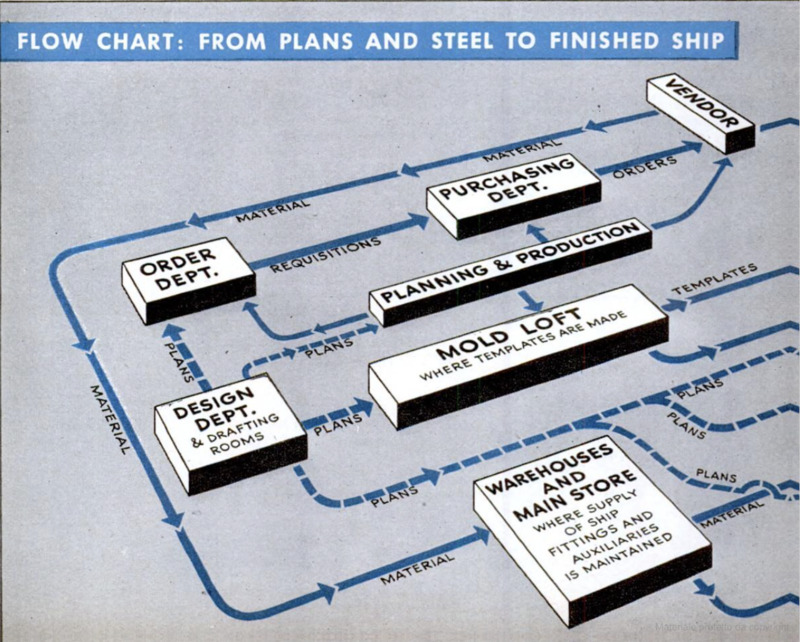

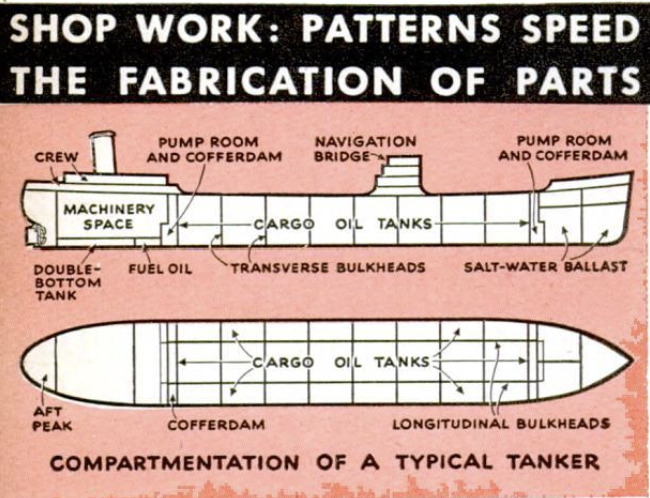

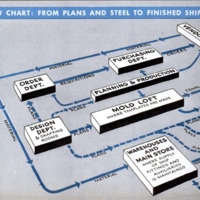

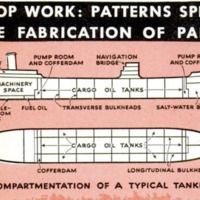

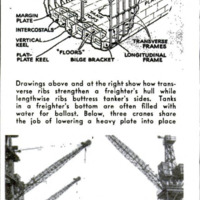

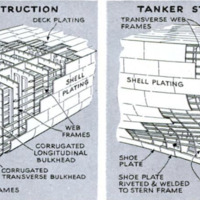

In building tankers, you have to have this

kind of shipyard. For it's a fallacy to be-

lieve that because most tankers look alike,

they're from the same blueprint. One may

have to be built for long hauls, another for

coastal service. A third may be designed to

carry airplane gas, while her sister will

pack cargo of crude or light oil. Still others

must vary in draft to solve the problems of

depth in foreign ports. In terms of con-

struction, that means installing power,

pumping systems, armament, and other

equipment that has been made to order.

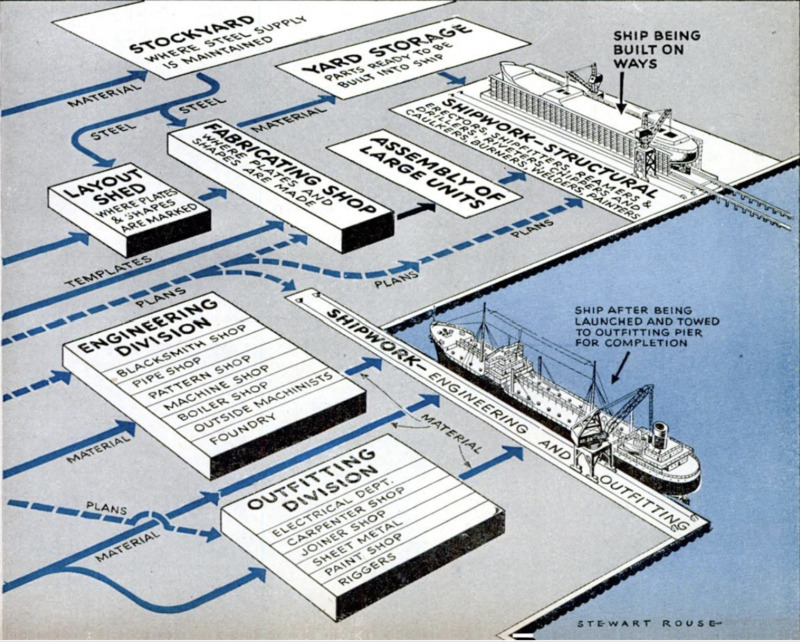

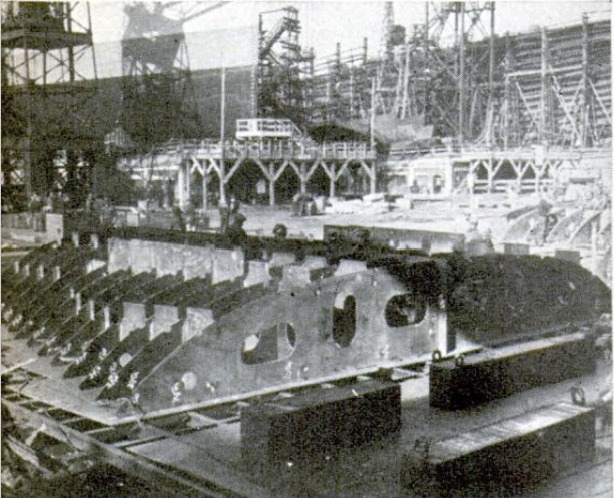

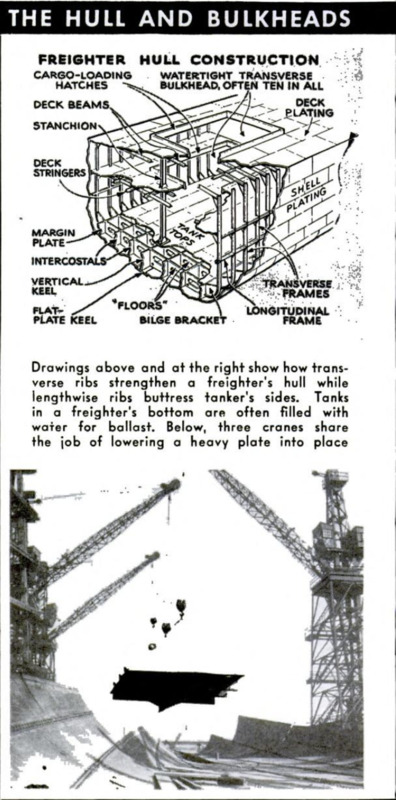

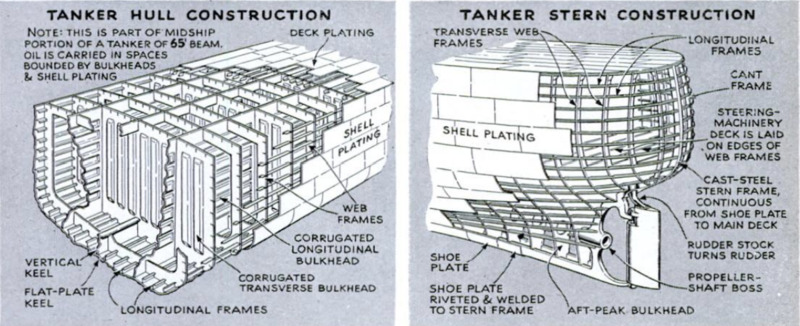

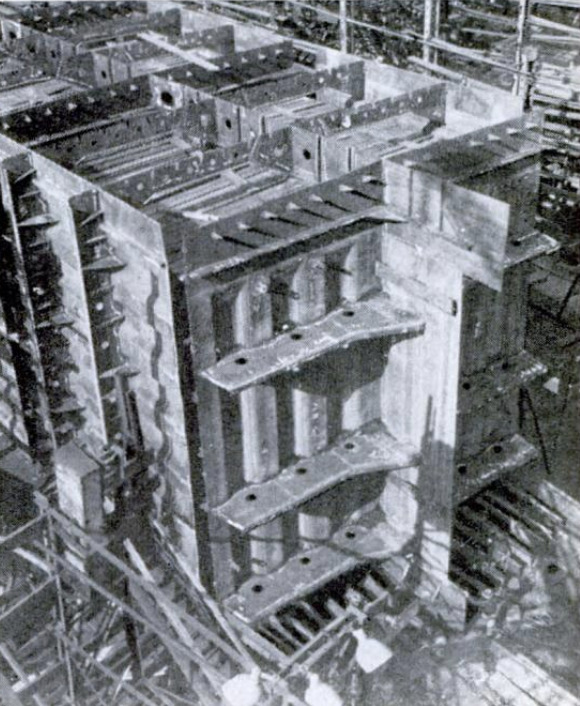

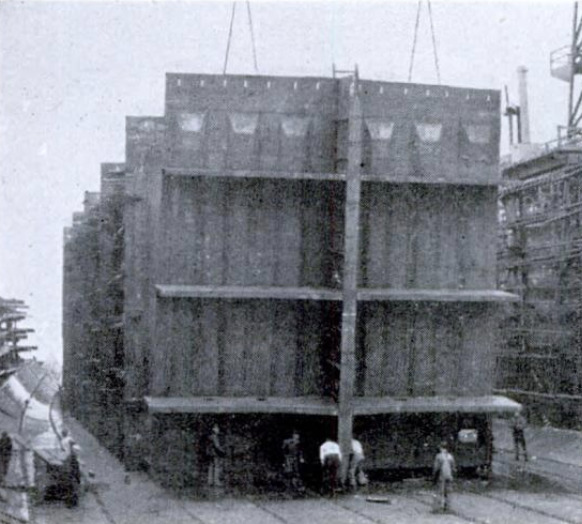

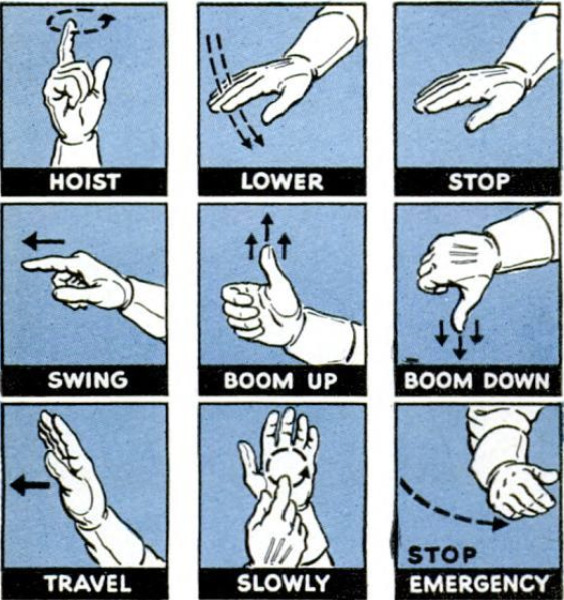

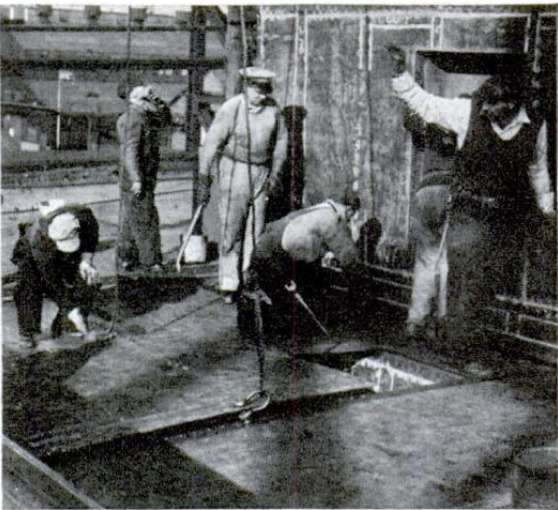

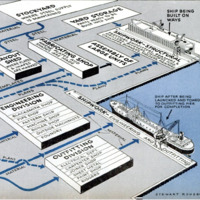

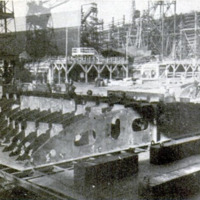

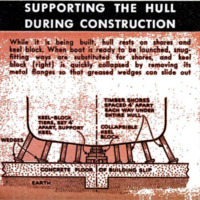

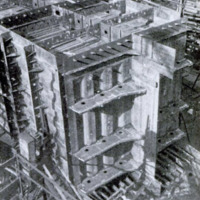

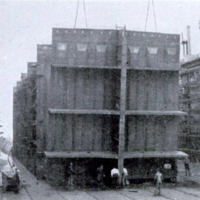

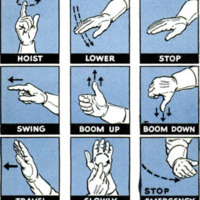

Tn making the 16,000-ton tankers that can

haul as much as 6,750,000 gallons of high-

octane gasoline on one trip across the At-

lantic or Pacific, the shipyard works are

necessarily of huge proportions. Scaffolding

that lines the ways towers into the air. The

tower cranes that stalk back and forth be-

tween the slips have a leg spread of 30 feet,

and from the revolving penthouse atop

them, their derricks can peek into a twelfth-

story window. They lift big preassembled

sections and lower them gently into place on

the growing ships. Sometimes, when a piece

is too heavy for a single crane, two or three

of them, working together like well-trained

giants from Mars, will share the load.

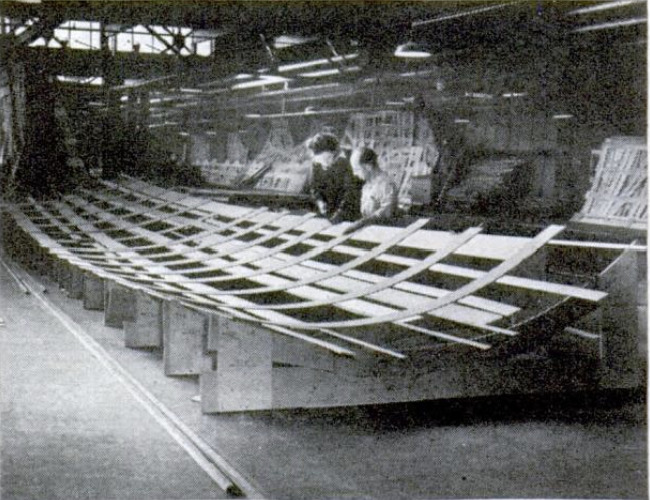

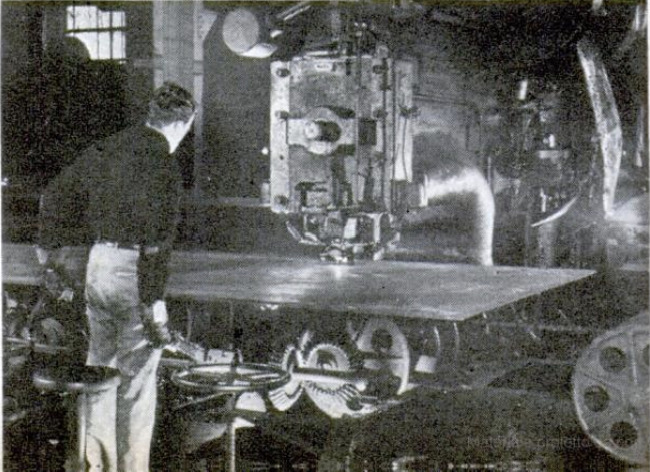

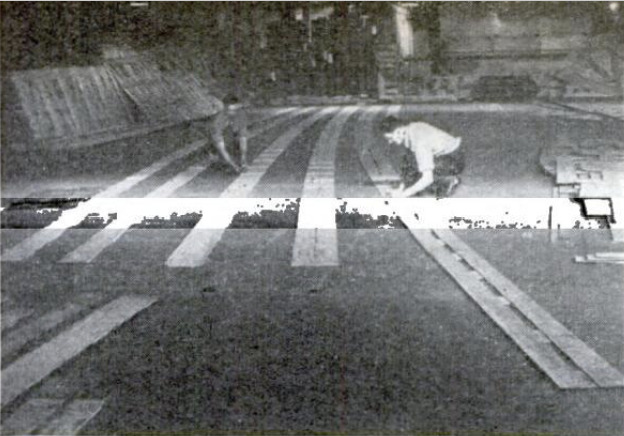

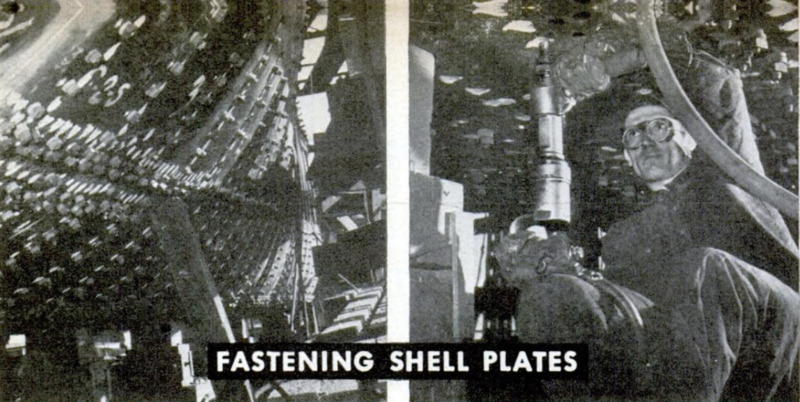

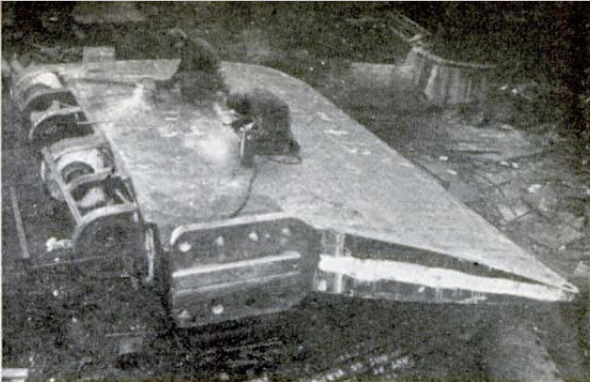

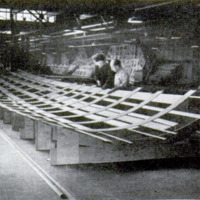

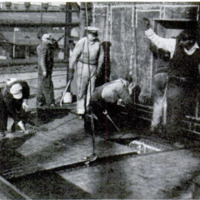

In striking contrast to the noisy ways is

the cathedral-like quietness of the great

formed cold; others, emerging hot from

near-by furnaces, are hammered into

shape; some, which have to be bent, are

twisted and held down with strong metal

“dogs” on the flanger’s slab—a large steel

platform having squares which are some-

what similar to those on a waffle iron.

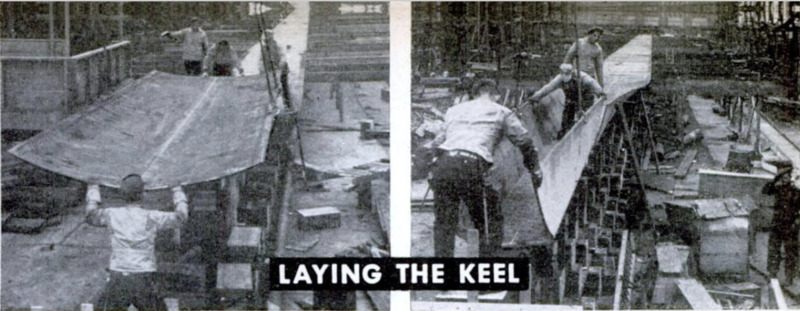

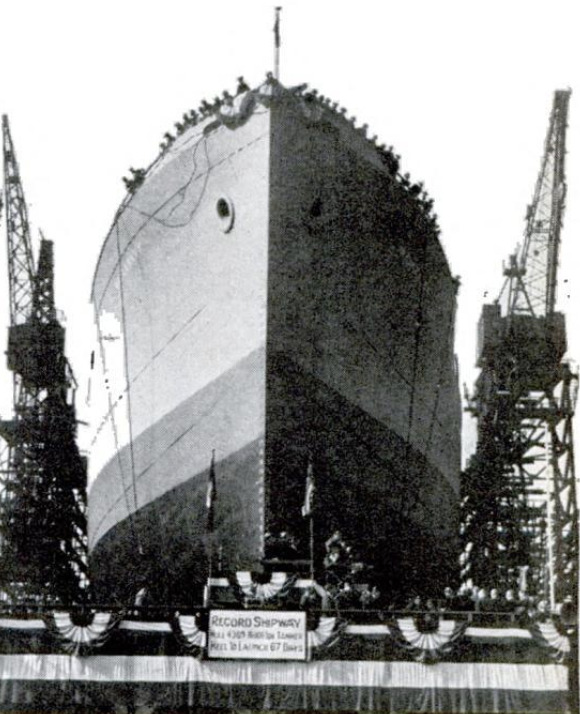

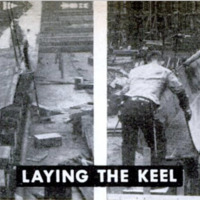

Construction time on the ways for tank-

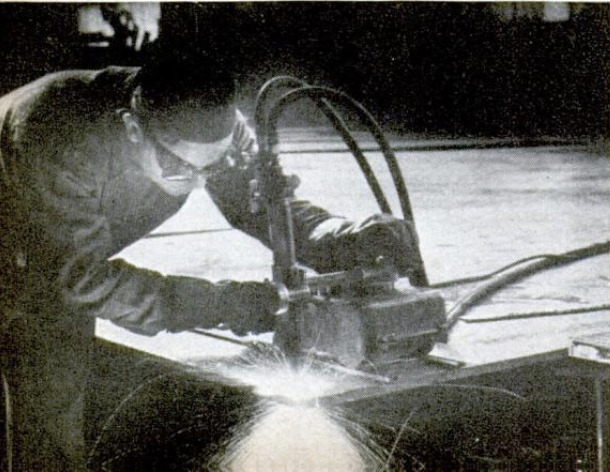

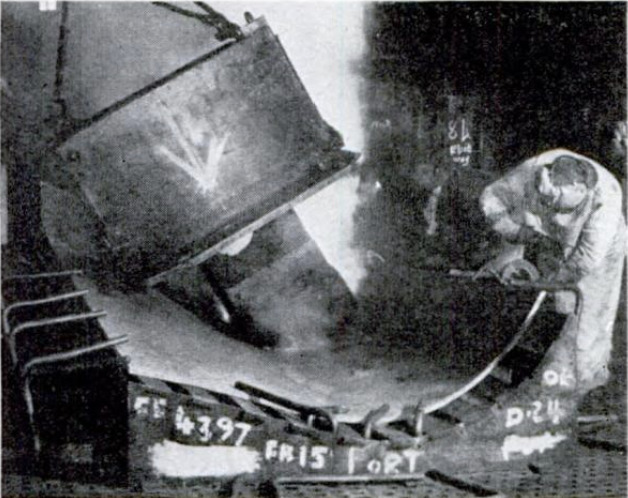

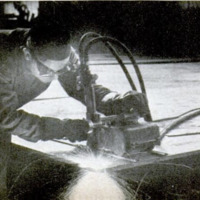

ers of 16,000 tons has been cut down from

41 months to 67 days, an Fast Coast

record which Sparrows Point shipyard

has recently set. This has been made

possible by new methods of handling steel

with flame —burning and welding. Using

a flame, a steel man can work with metal

as a tailor 17orks with cloth. With modern

torches and welding equipment, steel can

be taken apart and put together more

easily than wood.

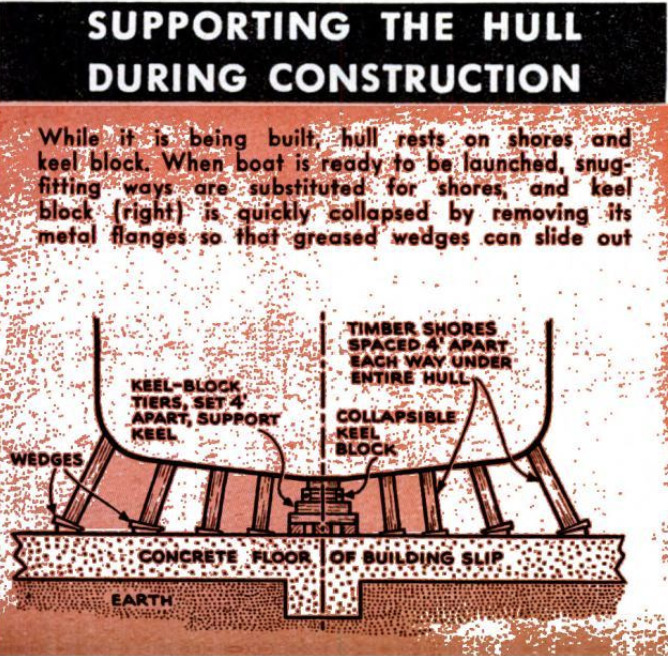

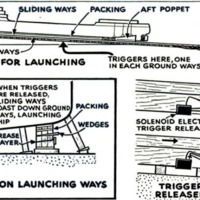

When a tanker is from 60 to 80 per-

cent completed, she is launched. That's

the big day for the yard, but it doesn't

mean that the craft is ready for service.

Many things have to be done before she

can carry her cargo on the high seas.

She's towed from the launching ways to

the near-by outfitting pier—or wet docks

—for finishing. There engineers, outfit-

ters, painters, and electricians give her

life. By man’s genius, she gets power to

swim around the world, power to see with

searchlight eyes and to hear and speak

through radio. Then off she goes to join

her sister tankers in supplying fuel to

keep the Allied motors of war roaring on

every battle front.

-

Autore secondario

-

Jack O'Brine (writer)

-

William W. Morris (photographer)

-

Stewart Rouse (illustrator)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1944-05

-

pagine

-

114-121

-

Diritti

-

Public Domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by

-

Lorenzo Chinellato

-

Alberto Bordignon (Supervisor)

Immagine 2022-05-03 213703.png

Immagine 2022-05-03 213703.png Immagine 2022-05-03 213723.png

Immagine 2022-05-03 213723.png Immagine 2022-05-03 213745.png

Immagine 2022-05-03 213745.png Immagine 2022-05-03 213759.png

Immagine 2022-05-03 213759.png Immagine 2022-05-03 213810.png

Immagine 2022-05-03 213810.png Immagine 2022-05-03 213820.png

Immagine 2022-05-03 213820.png Immagine 2022-05-03 213830.png

Immagine 2022-05-03 213830.png Immagine 2022-05-03 213843.png

Immagine 2022-05-03 213843.png Immagine 2022-05-03 213855.png

Immagine 2022-05-03 213855.png Immagine 2022-05-03 213905.png

Immagine 2022-05-03 213905.png Immagine 2022-05-03 213915.png

Immagine 2022-05-03 213915.png Immagine 2022-05-03 214145.png

Immagine 2022-05-03 214145.png Immagine 2022-05-03 214154.png

Immagine 2022-05-03 214154.png Immagine 2022-05-03 214206.png

Immagine 2022-05-03 214206.png Immagine 2022-05-03 214217.png

Immagine 2022-05-03 214217.png Immagine 2022-05-03 214239.png

Immagine 2022-05-03 214239.png Immagine 2022-05-03 214253.png

Immagine 2022-05-03 214253.png Immagine 2022-05-03 214321.png

Immagine 2022-05-03 214321.png Immagine 2022-05-03 214330.png

Immagine 2022-05-03 214330.png Immagine 2022-05-03 214341.png

Immagine 2022-05-03 214341.png Immagine 2022-05-03 214553.png

Immagine 2022-05-03 214553.png Immagine 2022-05-03 214603.png

Immagine 2022-05-03 214603.png Immagine 2022-05-03 214616.png

Immagine 2022-05-03 214616.png Immagine 2022-05-03 214627.png

Immagine 2022-05-03 214627.png Immagine 2022-05-03 214641.png

Immagine 2022-05-03 214641.png Immagine 2022-05-03 214654.png

Immagine 2022-05-03 214654.png Immagine 2022-05-03 214713.png

Immagine 2022-05-03 214713.png