-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

U.S. Dive Bombers and its pilots

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Title: Diving Artillery

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

MOST of us probably have wondered,

as we follow the war news, what it

is like to be a dive bomber. Only a

hero can know, of course, how it feels to

hurl one’s self into the cannon’s mouth. But

I recently undertook to find out what a dive

bomber’s job involves, during the training

period, and I ran into a number of surprises.

A dive bomber, for instance, is a keen

young fellow who eats his greens even more

religiously than Popeye the Sailor. He keeps

close tab on his weight, but he eats butter

in big chunks. Not only is he a perfect

physical and mental specimen, but a doctor

lives with him in his squadron, as alert to

his least symptom as is a mother watching

her first baby for a sign of sniffles.

The “blacking out,” the violent pull of

gravity, and most of the other melodra-

matic terrors we have been told about diving,

do not concern the dive pilot very much as

he hurtles toward the ground. He is too

intent on various wayward faults his plane

can develop in its falconlike course. And

until he meets a German or a Jap, his great-

est enemy is the common cold.

‘When I arrived at the air field and pre-

sented my credentials, Lieut. R. E. Strick-

land was hurrying out of his tent, buttoning

his flying jacket.

“You're just in time, come on,” he said.

“We've got a mission to bomb a motorized

column.”

Five minutes later, trussed into a para-

chute and strapped tightly into the machine-

gunner’s seat behind Bob Strickland, I was

flying at the head of the first dive-bombing

squadron to be activated by the United

States Army. We were six ships, low-wing

Douglas monoplanes from the Sth Squadron,

3rd Bombardment Group (Light). It had

taken up its new specialty last summer. As

its squadron commander, I suppose Lieuten-

ant Strickland might be called our Army's

first dive bomber.

‘We had flown for a half hour, high over

a jigsaw, contour-plowed landscape, when

an abrupt lurch of the airplane brought me

up sharply to attention. Strickland was

looking back at me over his shoulder. He

made a quick overhand, downward motion

with his hand. Now we were going to dive.

Ever since the Battle of France I had been

‘wondering a lot of things about dive bomb-

ing. Now at last I was going to find out the

answers. Hurriedly I looked over the side,

trying to see our target, but my inexperi-

enced eye was quite unable to identify it in

the finely etched panorama 9,000 feet below.

The plane's lurch had been a wobbling

signal for the squadron to move into string

formation. They were swinging over behind

us now, into echelon right.

Suddenly our plane seemed to stop in mid-

air. It felt as though a speeding driver had

slammed on his brakes. Indeed, that was

what had happened. Our diving flaps had

opened, pulled us up abruptly almost to

stalling speed.

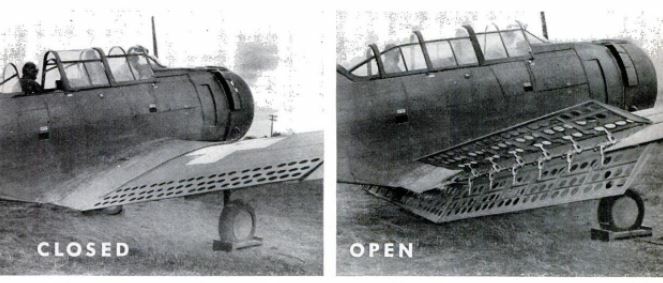

This dive-bombing plane, known as the

A-24, has one point which especially dis-

tinguishes it from other military ships, and

that is the trailing edge of its wings. The

inner half comprises two hinged metal sur-

faces, about a foot and a half wide, which

in normal flight are clamped close together.

Now some tremendous inner leverage had

swung them out, to a sharp angle from the

faces of the wing, one above and one below,

presenting firm resistance to the slip stream.

They acted as brakes, to cut our diving

speed to the point of human tolerance and

control. The flaps were perforated, col-

ander-fashion, with three rows of holes

about three inches in diameter, through

which the crowded air could rush. The in-

ner surfaces were painted red and against

the black-green of the plane's back they had

a living look, as though they might be the

distended gills of a hammerhead shark lash-

ing in for the kill.

I got ready to hang on. I rested my fore-

arms on a convenient metal hoop in front

of me and leaned forward. I planted my feet

wide apart, well away from the dual-control

pedals which moved between them. Back-

seat driving would hardly be appreciated

now.

We nosed over, then pulled up sharply and

ran forward again for an instant. Now we

nosed over again, straight downward, like

a canoe going over a waterfall.

There was a confused sensation of not

weighing anything. Pressure pounded in my

ears, and I swallowed hard to relieve it. I

was surprised not to feel that yawning un-

pleasantness in the abdomen which always

comes when an elevator drops too fast. I

glanced at the racing needle of my altimeter,

and we had dived 3,000 feet before the glance

was finished.

Looking ahead to see the target, I found

myself staring merely at a bulkhead and

Strickland’s head and shoulders. We had

dropped a mile before I realized the place |

to look was over his head, out through the

top canopy, where the sky should be. The

solid earth was close looming, rushing up

upon us. !

Our nose began to pull up. Now every-

thing was pushing upward against my sag-

ging muscles. My pillowed parachute be- |

came hard. Arms and feet were straining

under a suddenly terrific load. Some in-

exorable force was pushing my head down,

downward, chin into chest. My radio head- |

set fell off heavily, and a rushing roar en- |

gulfed me. It was about a four-G pull-out,

they told me later. That is, centrifugal

force and momentum had multiplied the

usual pull of gravity by four times. For an

instant I had weighed 660 pounds.

It was over quickly. The plane was slant-

ing downward gently and back over the side

our target could be seen. It was a train of

personnel carriers, armored cars parked

along a roadside. Soldiers were standing up

in them, unprotected, rubber-necking at the

planes. Theoretically the carnage was

terrific.

But it was a sight worth staring at. The

second plane was just pulling out at 1,500

feet, the third was half way down, while a

fourth was poised to strike. Down they came

like rockets in reverse.

Just how fast they were coming I don’t

know. Maybe it had taken 20 seconds to

dive a mile and a half. That would be about

250 miles an hour. It had seemed a lot

quicker.

Flaps closed and speeding, our planes

were skimming the tree tops now, pulling

into formation. Hedge-hopping, grass-cut- |

ting, skipping through the dew, hardly 20

feet above the foliage. Down close to the

ground was the safest place to be for an

escape. |

Dive bombing was invented by the U. S.

Navy, back in the 1920's, and was developed

secretly for some years. In 1932 somebody

let the cat out of the bag, and the idea was

seized by the German Luftwaffe, to be used |

with devastating effect in the land offensive |

of May, 1940.

‘To most of us dive bombing was then a

new and terrifying thought, but it was noth-

ing new to our Army airmen and they re-

mained convinced that for ground strafing

against troops their own method of light

bombardment was better. They had de-

veloped a low-flying, twin-engine ship, now

known as the A-20A (called the Boston by

the R.A.F.), especially adapted to appear

surprisingly over a clump of trees or a ridge

of land, sprinkle a large load of cream-puffs

from an altitude as low as 75 feet, and dis-

appear while the enemy was still surprised.

In another heavily armed form, known as

the Havoc, this same ship has become the

most effective night interceptor the British

have.

Developments supported this American

judgment to a great extent. While low fly-

ing soon demonstrated its value, the Ger-

man Stukas proved relatively ineffective

‘where local air superiority had not been ob-

tained. They had been so successful in

France because no strong pursuit forces

were against them. Also they were vulner-

able to antiaircraft fire.

But still diving had its definite usefulness,

against moving targets, and especially for

carrier-based craft against warships. Our

Navy developed it to the utmost. Meanwhile

the Stukas continued to prove their value

in attacks on British vessels in the Mediter-

ranean. Last year our Army began using

dive-bombing squadrons, borrowed from the

Navy, in all its maneuvers. A part of that

development was this pioneer squadron,

equipped with Navy-type planes, with which

I had now been flying.

Those few seconds of diving had demon-

strated a lot. For instance, without our own

fighters to protect us, we would have been

easy prey for enemy pursuit ships as we

came in and poised for the

dive. And a cool machine-

gunner directly below would

have had a very good

chance to knock us off. The

Stukas have found that out.

But of course if there had

been more of us, diving

from various directions, the

odds on our side would have

been improved.

Certainly there is no need

to minimize the velocity and

tension of such a dive as

this, but a good many melo-

dramatic notions had fallen by the wayside

too. For instance there was the matter

of centrifugal force. From what I had heard

of this kind of flying I had half expected to

black out as we pulled up from the dive, but

that proved to be an exaggerated notion.

The black-out is a common thing in some

types of aviation. When a plane makes a

sharp turn at high speed, the centrifugal

force is such that the blood is drawn away

from the pilot's brain and everything goes

black. He becomes blind for the moment

and if the strain continues he goes uncon-

scious temporarily. A pursuit pilot expects

to black out several times in an ordinary

day's rat race, but a dive-bombing pilot

doesn't black out unless he is in bad physical

condition. It is not so bad to go unconscious

in a bank at 15,000 feet, but it's a different

matter altogether if you are at less than

1,500 and roaring straight for the ground.

Probably the greatest prob-

lem of flying nowadays is

that machines have developed

beyond the ability of human

beings to endure them. This

is typified by the ability of en-

gines to operate efficiently at

an altitude where humans al-

most instantly die without an

oxygen mask and are oxygen-

starved even when breathing

the gas in pure form. So also

an airplane’s wings can stand

more G's of centrifugal force

than can its pilot. A healthy young man can

generally stand up to about five G's for two

or three seconds without blacking out. The

braking flaps of the diving plane have slowed

it down so that, at four G's, the black-out

danger is averted and also the ship can be

precisely controlled by a young man so well

in tune that his reactions are almost in-

stantaneous.

At luncheon after our bombing expedition

the pilots told some of the things they had

been doing during those tense seconds of the

dive. :

The most difficult thing was to trim ship.

The whirling propeller, driving an airplane,

develops torque, a twisting reaction which

tends to turn the ship to the left. For normal

flight the stabilizer is set permanently at an

angle to counteract this. But in a dive the

propeller no longer is driving the plane and

the torque is abated. So the off-center

stabilizer throws the ship into a skid. That

is, the tail slips off to one side.

Now, the whole principle of dive bombing

is that the plane itself is aimed at the tar-

get, with a telescope sight which runs paral-

lel to the longitudinal axis of the ship. If the

ship is moving in one direction and pointing

in another, aim is thrown completely off.

“In a dive you're practically standing on

your left rudder,” said the youngster sit-

ting next to me. “That corrects the stabi-

lizer and stops the skid. You've got to keep

the ball centered. You see, the bank indi-

cator on your instrument board has a ball

in a curved tube, and if the plane is skidding

that ball rolls off center.”

‘While thus trimming ship to avoid a skid,

the pilot must also select the proper angle

of dive. The sight is set to work with reason-

able accuracy at an angle between 70 and 80

degrees. Remember this is degrees and not

a percentage. An 80-degree dive is about 89

percent of a true vertical angle. Coming on

his target, the flyer picks his moment and

noses downward. Probably his angle is now

a bit shallow, so he pulls up and runs for-

ward a bit. He may perform this trial-and-

error process several times in the first 1,000

feet of descent, before he attains the proper

steepness and lets loose the

all-out plunge.

The dive is likely to begin

around 70 degrees and wind

up at 80. But if his angle gets

much steeper the pilot is in

trouble. The wings lose their

hold on the atmosphere and

the ship begins to rotate.

Corkscrewing, they call it.

The whole earth seems to

whirl, and in a crazy eccen-

tric fashion, for the pilot's

sight is of course not at the

axis of his rotation. Aim is lost, and in pull-

ing out of the dive the pilot has also lost his

sense of direction, which may be embarrass-

ing in a battle.

Diving is easier into the wind than with it,

because a tail wind may carry the plane

into too steep an angle. It may even carry

the ship beyond the target, so the wing load

is reversed. But a good pilot has to learn

to dive from any direction.

Having trimmed ship and got the proper

angle, the pilot's next job is to look through

his sight and hold his cross hairs right on

the target until, at about 1,500 feet, he is

ready to release the three bombs suspended

under his wings and fuselage. One hazard

developing at this moment, sometimes called

target fascination, is that the pilot finds

himself glued so fast to the target he can

hardly force himself to pull off. Those re-

porting this difficulty, however, have always

been able to master it.

In lunching with these pilots, I noticed

how much colorful foud there was on the

table. Servings of butter were several times

the usual size, and it was very yellow butter.

There were raw carrots, green vegetables,

lots of salad.

“TI don't like

this stuff worth a hoot, but Doc says eat it,

and so I do,” said the flyer across the table,

attacking a large plate of salad greens.

“We call it duty food.”

“Doc” was the squadron flight surgeon,

one of the most important men in this or any

other military-aviation outfit. He was filling

his flyers full of vitamins, especially vitamin

A, which is found in the carotene of butter-

fat, carrots, and greens. Carotene has some

mysterious chemical connection with the

adaptation of the eyes for night vision; and

these pilots were flying by night as well

as by day.

Dive bombing, as military flying goes, is a

simple operation; but, even more than some

other types of piloting, it requires split-

second reaction. The dietary care was but

one example of the strict regimen which it

was necessary for the pilots to follow in

order to maintain efficient operation.

‘The flight surgeon's job, as applied to this

or any other squadron, is another story.

But with the diving outfit there is one aspect

of his work which has to have special

emphasis. That is the watch he must keep

on the upper respiratory organs of the fly-

ers. The change of atmospheric pressure in

an 8,000-foot dive is so violent and sudden

that anything wrong with the nose or throat

is likely to give the pilot great trouble with

his ears.

I had an example of this myself, the

second time I tried a dive, forgetting that

I had a slight nasal irritation. Watching

the ground rushing up at us, I also forgot

to swallow and thus ventilate my middle

ear. Half way down, there came a sudden

sharp jab of pain in my left ear, which

increased with each foot of dive until by

the time we reached the ground the pressure

on the eardrum was agonizing. It was a

half hour before the pain was relieved, three

weeks before that ear felt normal again.

They explained to me what had happened.

The eardrum separates the outer and inner

ears. The outer ear is connected directly to

the atmosphere, but the inner ear is thus

connected only by the small Eustachian

tube, which runs into the throat at the nasal

pharynx. The pressure in these two cham-

bers should be equal. When we climb in an

airplane, atmospheric pressure decreases,

and the compressed air in the inner ear

easily escapes through the Eustachian tube.

But when the process is reversed, the air

has a much harder time getting back. Swal-

lowing helps it. That's the reason for the

chewing gum they give you in an airliner.

When descent is gradual, there is usually

no special problem.

But in a diving descent, the pressure in-

creases very suddenly, by more than one

third within a few seconds. At 9,000 feet the

barometric pressure is 21.38 inches of mer-

cury, while at 1,000 feet it is up to 28.86

inches. Under this sudden change the soft

mouth of the Eustachian tube is likely to

collapse, like a rubber tube which is sucked.

Then the increasing pressure seals it against

the entrance of air and the eardrum has to

absorb the pressure by bulging inward.

The least cold in the head or sore throat,

by swelling the opening of the tube or

clogging it, exaggerates these difficulties.

In addition, any throat infection is likely to

be carried into the ear by the inrush of air.

At the least sign of such trouble, the flight

surgeon puts the dive bomber down for duty

not involving flying.

This Sth Bombardment Squadron is a

venerable outfit, with traditions going back

to World War days. It had a great deal to

do with developing the Army's technique

of low-level attack bombing. But except for

the commander, its veterans were trans-

ferred when it took up its new specialty.

These dive bombers were youngsters fresh

out of flying school, hot With enthusiasm

for the development of what was for the

Army a new type of flying.

They had learned it quickly, for as

military flying goes it is a very simple thing.

It involves none of the intricate teamwork

between pilot and bombardier in using a

bomb sight, none of the elaborate correc-

tions required by level-flight marksmanship.

Dive bombing is basically just another

maneuver in the flying of an airplane, and

after a few principles are explained to the

fiyer, the rest is practice. Of course there

are tricks to it, just as there are tricks

about making a basketball go through the

hoop, but those are within the realm of

military secrecy.

Up to now we have heard of dive bombing

mainly during the German offensives in

Europe. The next time it breaks into the

news may well be when the American Fleet

engages the Japanese. All our naval pilots

are dive bombers, along with their other

skills, and the art is one of our main naval

weapons. With our war now centering in

the Malay Archipelago, a combination of

sea and air campaigning, dive bombing may

well assume an importance greater than

has ever been anticipated.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Hickman Powell (Article Writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1942-04

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

90-96, 220, 222

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public Domain (Google Digitized)

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Roberto Meneghetti

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Popular Science Monthly, v. 140, n. 4, 1942

Popular Science Monthly, v. 140, n. 4, 1942