-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

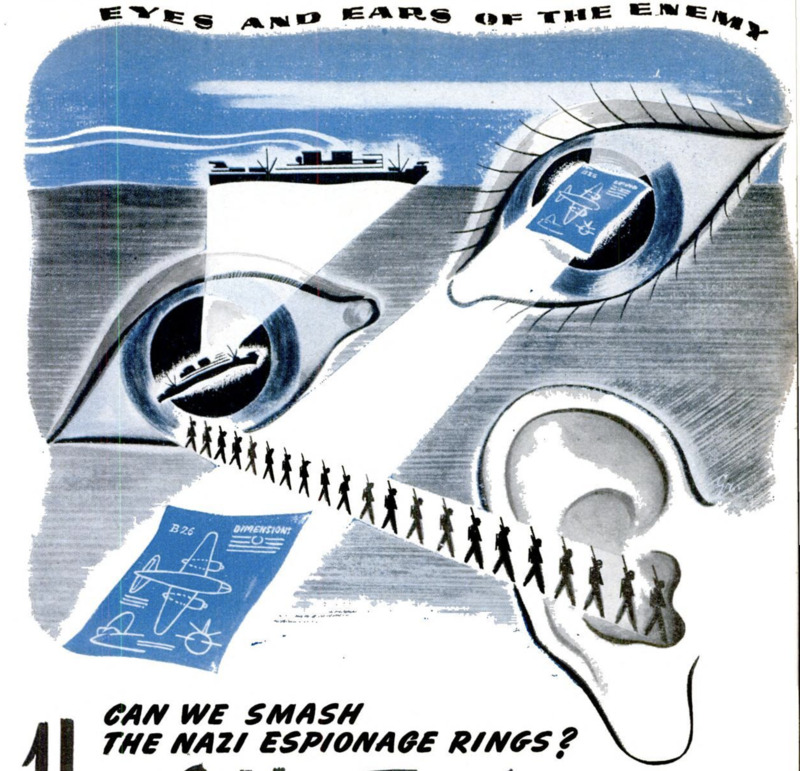

Can We Smash the Nazi Espionage Rings? How G-Men trap Axis Spies

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Can We Smash the Nazi Espionage Rings? How G-Men trap Axis Spies. Using Every Means of Scientific Detection, the FBI Is Outwitting Gestapo's Best Secret Agents.

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

IN A little waterfront tavern at Port Rich-

mond, N. Y., few patrons even noticed the

stoop-shouldered, 57-year-old porter, busy

with mop and pail. Anyone taking the

trouble to inquire would have learned that

he operated his pleasant brick home in

near-by Tompkinsville as a boarding house

for service men, and that he was one of the

most zealous air-raid wardens to be found

in the vicinity.

Yet, at this writing, he faces a long

prison term or the electric chair, as a self-

confessed Nazi spy. And a United States

Attorney declares, “This is one of the most

important arrests made in an espionage

case in this country since the declaration

of war. The FBI is entitled to full credit

for its surveillance and eventual capture of

this man.”

His house, Federal Bureau of Investiga-

tion agents pointed out, topped the highest

point on all of Staten Island. From his attic

windows he had a perfect view of Allied

ships bound out of New York Harbor, and

could relay information of the highest value

to U-boats ready to intercept them. What

he did not see for himself, he could pick up

from careless conversation at the tavern

where he worked—and at others that he

made it his business to visit in off hours.

His roomers, too, may have unwittingly

furnished him with information of great

importance to the Nazis.

Through underground channels, G-men

say, he was able to enlist the aid of a

most helpful accomplice. Well trained in

engineering, this man was employed in an

Eastern airplane factory. The engineer

could supply just what the Nazis particu-

larly wanted—production figures for Ameri-

can planes, and diagrams of the latest mod-

els. Among other things, he turned over to

his_fellow-conspirator a complete set of

highly confidential plans for a new bomber.

Delighted with what he could now forward

t0 his superiors in Germany, the Tompkins-

ville spy pressed $100 into the engineer's

none-too-reluctant hands. It was a hand-

some sum among Hitler's underpaid spies,

even for the risk taken by the engineer. (He

was to find out about that later, when FBI

men caught up with him; he, too, has been

arrested and has confessed.)

More industrious than imaginative, the

Tompkinsville agent followed a familiar

method—the “mail drop” system—to get

his information to the Fatherland. He typed

innocent-looking letters to “friends” in neu-

tral foreign countries. Victory gardens,

‘Washington's Birthday, and California wine

came in for mention, and there were expres-

sions of pleasure at American victories over

the Japanese. But the letters also bore, in

invisible ink, information on arms ship-

ments, troop movements, convoy sailing

dates, and industrial production figures. To

make the ink, the writer dissolved in water

a white powder, which he had been told to

call an eye wash if questioned. Traveling

by Clipper mail planes, the letters were in-

tended to reach foreign Nazi sympathizers

who would speed them to their destination.

‘The invisible ink, of a kind well known to

expert searchers for hidden messages, was

the one weak spot in an otherwise flawless

sctup. When the authorities examined the

Clipper mail, they quickly detected it. In-

stead of going abroad, the letters went to

the FBI, which took over the months-long.

task of tracing them back to the sender.

Of course, he had not been obliging

cnough to give a return address. The Tomp-

kinsville postmark was the only clue. Ques-

tioning postmen, the G-men patiently ran

down one false lead after another, until

their search narrowed to the street where

the suspect lived. When they finally nabbed

him, his nearest neighbors were amazed to

learn of his clandestine activities.

In the first World War our organization

for combatting spies and saboteurs— of

which this writer was a member—was a

hastily improvised hodgepodge of several

Government agencies and an amateur outfit

whose well-meaning members had a discon-

certing habit of getting under the profes-

sionals’ feet at crucial moments. President

Roosevelt averted a repetition of that mis-

take when, in 1039, he designated the

Federal Bureau of Investigation and our

military and naval intelligence services to

handle all espionage and sabotage matters,

with the FBI as the co-ordinating agency.

Since then, the G-men have investigated

thousands of cases involving reported es-

plonage and sabotage. These range from

honestly mistaken “scares” to life-and-death

battles of wits with master spy rings.

No less than 174 “parachute landings” in

this country were reported by anxious citi- |

zens between June, 1942, and last March,

according to J. Edgar Hoover, director of |

the FBI Every report was investigated and |

proved unfounded. What the observer usual-

ly saw was a bird or kite.

Similarly, at a time when “U-boats” were

being sighted along the coasts in fantastic |

numbers, a high Navy official remarked,

“They'll be sceing flying submarines next.”

He was right. A woman air-raid warden in

an eastern coastal area agitatedly reported

that a submarine was flying overhead. She |

had never before seen a U.S. Navy blimp. |

Of the many fanatics and crackpots who |

have fancied themselves as “lone wolf” Nazi

saboteurs, perhaps the boldest was a Ger- |

man who attempted to sell the formula of

an antifreeze compound for airplane motors

to the United States Government. FBI

agents spoiled the deal when they overheard

the German's private comment that a few

drops of picric acid, added to the compound

by a saboteur, would wreck each engine.

But these are small fry, compared with

organized spy rings that the FBI has

smashed. Headed by top-notch espionage

men trained in a special German school,

they work something like this: |

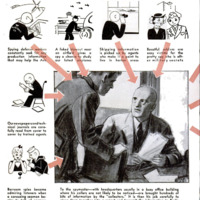

In charge is a director—the spymaster.

Usially he has his headquarters im a reper

table and busy office building in which call-

ers are not likely to be especially noticed,

and conducts his affairs behind doors let.

tered with the name of a real or—more

often—phony business concern. Reporting

to him are a varying number of “collectors”

who do the routine spying. All of them are

inconspicuous people and most of them hold

down inconspicuous jobs. They are wait-

resses in military-area. lunchroom who re.

port that last night Private Smith was

Erouching because wearing the tin hat Just

fasued to him gave him a headache; factory

workers who tell the director how they

overheard the super telling the foreman

that the front office had got an order for

20,000 more of those machine-gun mounts:

shabby men who ait all day in hail bed-

Toms, fine-combing newspapers and tech.

Bical Magazines for pertinent news ftems.

Pieced together by a highly trained spy.

master, dozens and even hundreds of these

bits and pieces of information make up

most model-1043 espionage reports.

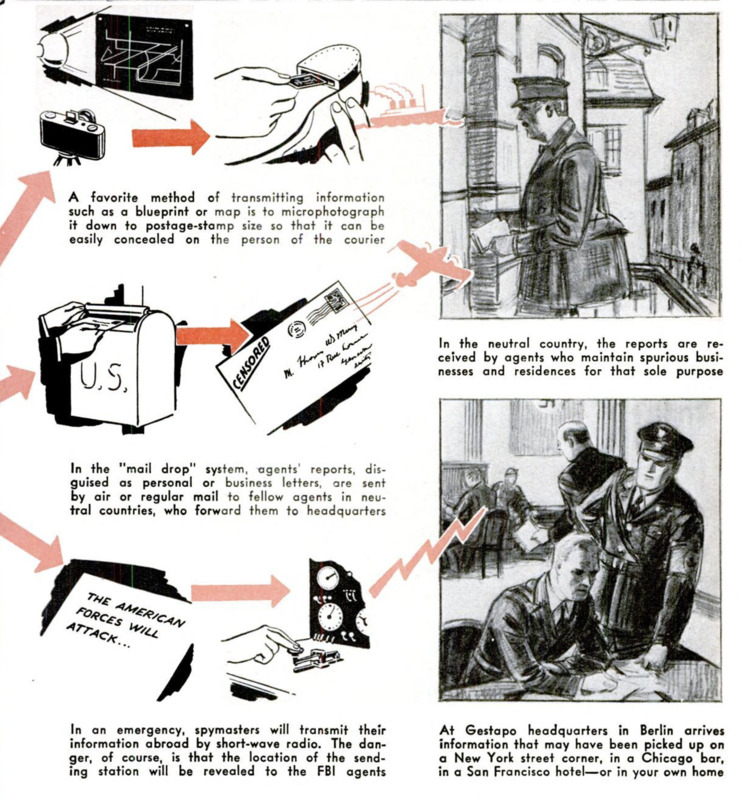

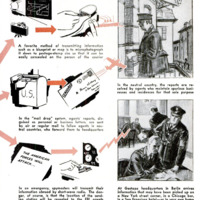

“Transmission by short-wave radio is of

course the quickest means of overseas com.-

munication, and It is used by spies for send.

ing news of ship sailings and large-scale

troop movements—i/ (and in these war

days it is a mighty big if) they dare use

their transmitters. When speed in delivery

is not essential, espionage reports usually

are sent by air or regular mail, addressed

to'a “mail drop” In some neutral country

sy, a spurious business ofice maintained

for the sole purpose of receiving mail from

spies operating in enemy or untriendly coun.

tries and forwarding it to Germany or

Japan. As in wartime all foreign-addressed

mail ls subject to censorship, espionage

communications sent by post Tust be cam:

ouflaged to avert suspicion. Usually the

camouflage is a natural-sounding business

letter typed on one side of the sheet. This

may be a coded message, or may serve as a

blind for another in invisible ink.

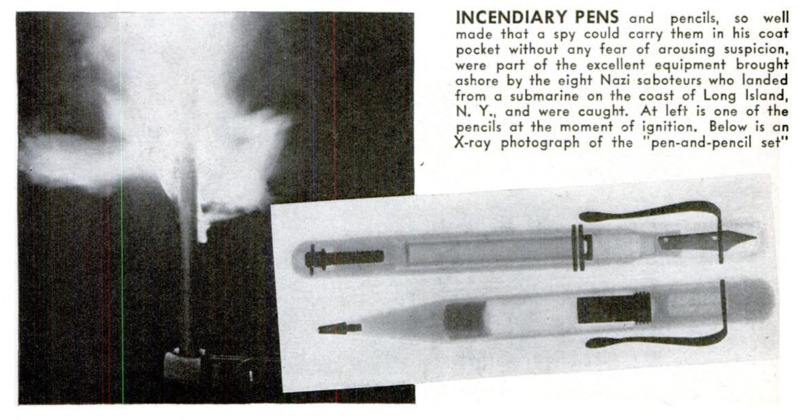

Blueprints, maps, sneaked tracings of de-

signs and plans, and important documents

which must be sent abroad in unabridged

form usually are microphotographed, in the

manner of a V-mail letter, by an expert as-

signed to the ring. The microfilm, little

larger than a postage stamp, is carried con-

cealed on the person of a courier.

Illicit radio transmitting stations are lo-

cated so quickly and accurately by the many

scores of Federal Communications Commis-

sion listening posts scattered all over the

country that spies seldom risk using them

unless they can be moved in a hurry.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Arthur Grahame (writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1943-10

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

49-53

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public Domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Matteo Ridolfi

-

Alberto Bordignon (Supervisor)

Popular Science Monthly, v. 143, n. 4, 1943

Popular Science Monthly, v. 143, n. 4, 1943