-

Titolo

-

Nightmares to order-for Hitler. The History of Ten Production Heroes whose "Brain Children" Have Become Headaches for the Axis.

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Nightmares to order-for Hitler. The History of Ten Production Heroes whose "Brain Children" Have Become Headaches for the Axis.

-

extracted text

-

IT REQUIRES no great imagination to re-

| construct the scene at Hitler's headquar-

ters on the night that the British Eighth

Army blew the lid off at El Alamein. Rom-

mel had just sent a wire to his boss, saying

he had that mouthy little squirt, Mont-

gomery, backed up against Alexandria and

was about to blast him with those invincible

German 88-millimeter tank guns and then

sweep all North Africa bare of British re-

sistance with a thousand tanks flying the

black swastika. Heil Hitler!

So the little house painter who had painted

whole cities red with human blood crawled

into bed to dream of his coming triumph on

the morrow. Before dozing off, he had a few

little details to decide. . . . No, he wouldn't

head the triumphal parade through the

streets of Alexandria. That might interfere

with a previous date to stand in Red Square

in Moscow and watch the Kremlin go up in

flames. Let the little fathead Mussolini play

stooge for him at Alexandria. Now for a

good night's sleep.

But shortly after dawn the arch murderer

of all time was wakened by an apologetic

aide bearing a dispatch from Rommel.

It read: "Two-thirds of my tanks de-

stroyed by new secret weapon of the enemy.

Making strategic withdrawal to Halfaya

Pass, where I propose to ambush and de-

stroy the British Eighth Army. Heil Hitler!"

That morning Hitler's breakfast consisted

solely of the fringe of his bedroom rug,

which he tore off in great mouthfuls in frus-

trated rage. They can't do this to me—me,

The Fuehrer!

Just the same, the British Eighth Army

had done it. But not entirely on its own. Six

thousand or more miles away, in the buzzing

war factories of the United States, ten

Yankee mechanics and engineers had each

furnished an idea which put an end for all

time to Hitler's nights of dreamless sleep.

Which one of these ten Yanks deserves the

title of chief sleep buster to Hitler is neither

here nor there. It was the combination of

their ideas, skillfully employed by their

tough fighting comrades of the British

Eighth Army, that robbed Hitler of a vic-

tory already counted in the bag and even-

tually made second-hand merchandise out of

every gun and plane and tank with which

Rommel had started out to tour Africa.

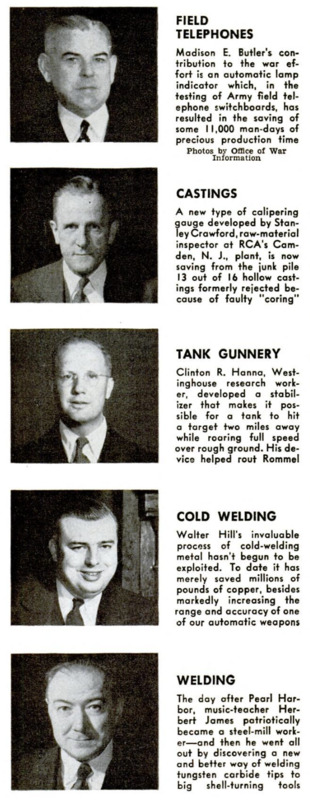

Perhaps the most spectacular of these |

Yank ideas was the one contributed by Clin-

ton R. Hanna, of the vast Westinghouse

arsenal at East Pittsburgh. A hair-raisingly |

short time—as the Army measures such

events—before the Battle of El Alamein, re-

search worker Hanna left the East Pitts-

burgh plant for one of the ordnance proving |

grounds with a new device almost as com-

plicated as the now famous Norden bomb-

sight. |

The device was transferred to a waiting

tank. Hanna pulled on a suit of coveralls,

fitted on a tanker's helmet, and crawled

aboard.

The big tank lurched into motion, rum-

bling toward the crest of a low ridge. Beyond

that ridge, about two miles away, was the

target, a board shack about the size and |

shape of a German tank, built low to the

ground and no easy mark to hit. Up the

back slope raced the tank, with Hanna |

strapped in the gunner's seat, the ponderous

war machine roaring and grinding and

lurching erratically. Then over the top! |

Suddenly, Hanna's finger closed on the

trigger. The tank's heavy gun dived back

on the recoil slide. The tank commander

stopped his machine and peered down below

at Hanna.

“What's the matter, mister? Your finger

slip?”

“No, Captain. We were on the target. So

I let go.”

Just then a walkie-talkie observer, sta-

tioned in a bombproof shelter close to the

target, piped up: “Direct hit. Target de-

stroyed. Proceed to next firing problem.”

How can the new Hanna-equipped Ameri-

can tank make direct hits on enemy tanks

two miles away while on the gallop?

The answer lies in a robot known as a gyro-

stabilizer, which keeps the gun barrel at

a fixed elevation and the target in focus

of the gunner’s telescopic sight despite the

pitch of the tank. The gunner can fire

quickly and effectively, making only slight

manual adjustments when necessary.

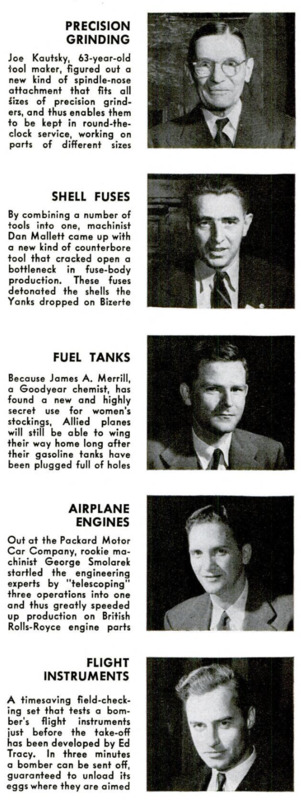

Without knowing at the time what a wow

of an idea bit him, Dan Mallett, a machinist

in the Borg-Warner Mechanics Universal

Joint plant at Rockford, Ill, pitched another

Yankee strike over the pan in that

same battle. After the British Eighth

Army had retreated for the last time,

back from Tobruk to El Alamein, it

was short of tanks, short of guns,

and desperately short of shells. Every

resource of the United States was

strained to the utmost to re-equip the

British Eighth Army before it was

too late.

Dan Mallett’s contribution was an

idea for a new counterbore tool that

opened wide a bottleneck in fuse-

body production. Dan's idea was

simple—just combining several dif-

ferent tools into one. But nobody, in-

cluding the company’s high-salaried

production engineers, had thought of

it before. Yes, Dan Mallett, hard-

fisted Yank mechanic, pitched one

down the groove that helped blast

Rommel out of El Alamein and kept

him back-pedaling for 1,600 miles.

More shells, with Dan Mallett’ per-

sonal sentiments attached, drove the

German tanks back at Kasserine

Pass; they kept on coming in in-

creasing quantities until the Yank

Second Army had to race like hell to

beat the British Tommies—also

pitching fuse bodies a la Mallett—

into Bizerte.

Bad news 1s supposed to come in |

threes. Yes, and then some, maybe.

Joe Kautsky, a 63-year-old toolmaker

for the Link Belt Company, of In-

dianapolis, Ind., is entitled to claim a |

little credit for giving Hitler at least

one bad night.

Joe's company was making small

hardened and ground precision parts

for any of the big prime contractors

who wanted them made “close” and

made right. The only trouble was

that contractors for both tanks and

airplane engines, for instance, wanted

at the same time all the production

available from the same size grind-

ing machines in Joe's plant. That

meant that some days a number of

the larger grinding machines would

stand idle while the smaller machines

were smoking hot from overloading.

Joe devised an entirely new type of

spindle-nose attachment that would |

fit all sizes of machines, so that they

could all be thrown into production

of any size part. Joe's spindle-nose

attachment is now being used all

through the war-production program.

Heil Hitler! |

Coming in on a wing and a pray-

er—! The Yank Flying Forts are

able to do that, even with bullet holes

through every gas tank, because

James A. Merrill, research chemist

for the Goodyear Tire and Rubber

Company, found another use for

ladies’ stockings. That is all censor-

ship will permit. One of Hitler's

worst nightmares.

And just as though it weren't a

dirty enough trick to play on Hitler,

keeping the Flying Forts flying after

they were shot full of holes, along

comes another Yank with an idea

hotter than a depot stove for keeping

their bombs dropping smack on their

targets. Edwin C. Tracy, field service

man for the RCA Manufacturing

Company, Camden, N. J., plant, has

developed a field-checking set that

can be lugged right into a bomber

Just before taking off, so that its

flight instruments can be calibrated

to frog-hair accuracy. Now, in three

minutes’ time, instead of the many

days required to dismantle a plane's

flight instruments and put them

through elaborate laboratory tests,

Ed Tracy's checking instrument can

send a bomber roaring off the run-

way with every bomb guaranteed to

1and where the bombardier points his

Norden bombsight. The only one left

guessing is Hitler.

Walter P. Hill, a former turret-

lathe operator and automobile-repair

mechanic, and now a development

engineer for the Wolverine Tube Di-

vision of Calumet and Hecla Con-

solidated Copper Company, of De-

troit, has staged a one-man blitz all

his own and there would be dancing

along Unter den Linden tonight if

Walter would only develop a perma-

nent case of amnesia and forget all

he knows about how to make cold

metal weld itself to cold metal.

Reduced to its simplest elements,

Hill hit upon the idea of taking a

brass tube and, with a small tool that

costs about two dollars or less to

make, closing the end of the tube

without the use of any externally ap-

plied heat, such as from a weider's

torch or a brazing flame. He starts

with a cold plece of metal and finish-

es with one end of the tube closed in

a perfect metallurgical weld. After

he had worked the bugs out of his

process on brass tubing, he discov-

ered the same process worked on

steel tubing!

There is no limit in sight, yet, for

applications of the Hill process for

cold-welding metal. At least a half

dozen appli-

cations of it to war matériel are hush-hush

subjects of test at the Army and Navy prov-

ing grounds.

Another of the Unholy Ten—Berlin pa-

pers, please copy—who have been giving

Hitler frightful nightmares is a former

music teacher. The day after Pearl Harbor,

Herbert Rudolph James turned over his class

of music pupils to another teacher and took

a job as a steel-mill worker at the National

Tube Company, McKeesport, Pa. His boss

tried to teach Herbert James how to weld

tungsten carbide tips on big shell-turning

tools. But, frankly, Herb thought his boss

turned out a lousy job, for a little while

after the expensive tip had been welded to

the tool shank, the shell-lathe hand came

back with it—broken at the weld.

At that point Herb took off on his first

solo flight as a war-production idea man.

He rigged up an iron-pipe frame and

clamped three acetylene torches to it so that

the flame from each would play directly on

the tool. Then with all three torches going,

he thrust a tool shank and tungsten carbide

tip into this atmosphere of incandescent gas

—and out came a perfectly welded tool that

outlasted the single-torch-welded tool sev-

eral times. The same result could have been

obtained from an atmosphere-controlled

electric furnace, sure. But such furnaces

were not available. So, another spook under

the bed at Berchtesgaden.

Out at the Packard Motor Car Company,

27-year-old George Smolarek one day took a

series of operations laid out by the Packard

professional engineers and telescoped three

of those operations on a British Rolls-Royce

airplane-engine part into one operation. It's

a crime how many times since George

Smolarek pulled that idea out of his cap

those Packard-built Rolls-Royce engines

have plastered the daylights out of the

German Luftwaffe.

Yes, an idea can kill farther than a bullet.

Stanley Crawford, a sharpshooting raw-ma-

terial inspector at the RCA Camden, N. J.,

plant, saw entirely too many castings being

junked because the cored interior was not

in proper relation to the outside surfaces.

This trouble was caused by the cores float-

ing after the hot metal was poured into the

molds at the foundry. Such castings failed

to clean up in subsequent machining opera-

tions, at a great loss in both material and

priceless man-hours. Crawford designed a

special type of calipering gauge which de-

termines the relationship between the in-

side and outside surfaces of a casting, ena-

bling the machine operator to “favor” any

shifting of the core. By the use of this

caliper, 13 out of the 16 castings formerly

rejected in raw-material inspection, or

junked on the machine line, are now saved.

Just that much more Yankee hardware

headed Hitler's way.

The man who has probably caused more

“talk” than any other Yankee mechanic in

this war is Madison E. Butler, an assistant

chief inspector of Stromberg-Carlson Tele-

phone Manufacturing Company, Rochester,

N. Y. He was assigned to the job of testing

field-telephone switchboards. When the first

board came off the line, it took Butler and

an assistant five whole days, with plenty

of overtime, to check its maze of circuits.

And there were 1,100 more following closely

on its heels!

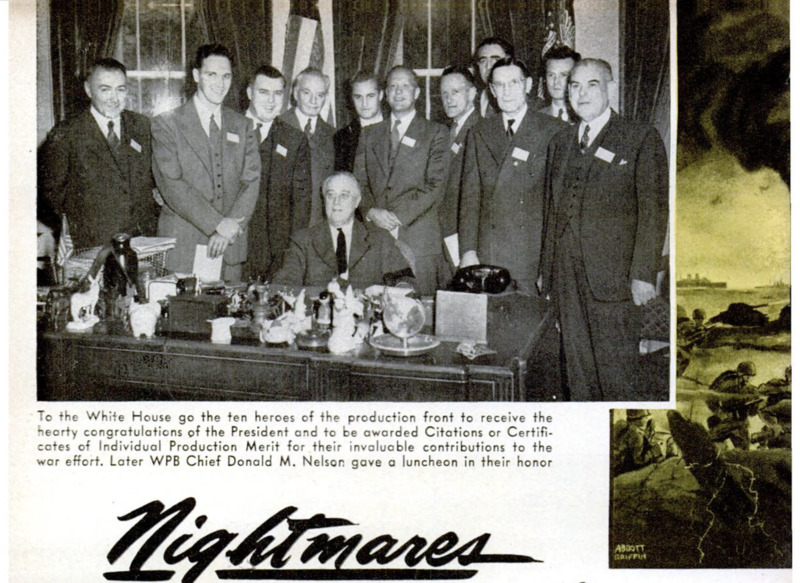

When Butler joined the Unholy Ten who

were called to the White House and con-

| gratulated for their individual contributions

to the hell-for-leather drive to manufacture

more nightmares for the Nazis, this is how

his citation read: “You have earned this

high honor by developing an automatic

lamp-indicator for testing Army field-tele-

phone switchboards, thereby saving 11,000

man-days.” Figure that out and it amounts

| to almost enough men to form a streamlined

mechanized division for one day of battle.

In other words, Butler came to bat with a

foxy test rig with which one man could do a

Detter Job of testing a switchboard in less

than two hours, compared to the original

| testing time of two men sweating out over-

time for two days.

Meanwhile, the great American pastime of

manufacturing nightmares to order for Hit-

ler and his chums goes on. The records of

the Production Idea Exchange Branch of

War Production Drive Headquarters, the of-

ficial agency of the War Production Board

charged with the job of digging out these

unsung heroes of the Production Front and

plowing their ideas back into all possible

war production channels, shows that well

over 100,000 smart Yankee production ideas

have been pulled out of the hats of American

war workers. An impressive percentage of

these ideas have been outstanding, such as

the ten described in this article. More are

turning up every day.

Is it any wonder that the man who could

sleep like a baby with the murders of mil-

lions of innocent victims on his conscience

now is having the heebie-jeebies every night

when he pulls the covers over his ears?

-

Autore secondario

-

Ray Millholland (writer)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1943-10

-

pagine

-

74-77, 202, 204

-

Diritti

-

Public Domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by

-

Matteo Ridolfi

-

Alberto Bordignon (Supervisor)