-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

Road Maps of the Sea Guide our Fighting Ships

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Road Maps of the Sea Guide our Fighting Ships

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

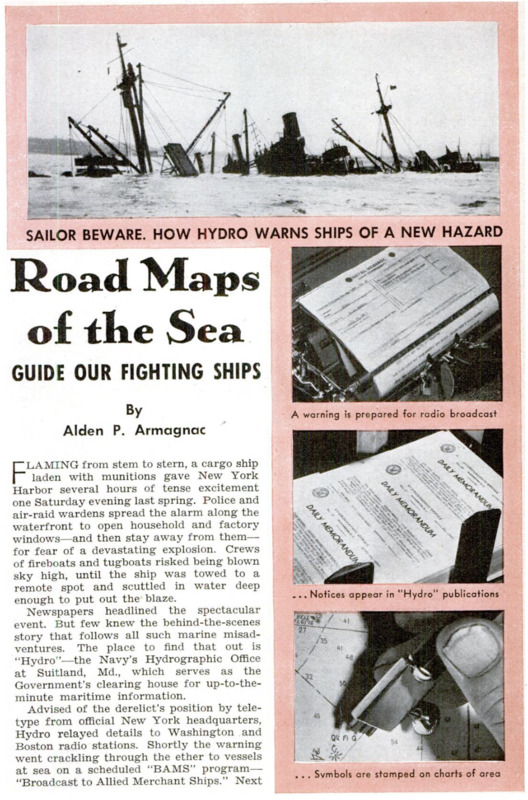

FLAMING from stem to stern, a cargo ship |

laden with munitions gave New York |

Harbor several hours of tense excitement

one Saturday evening last spring. Police and

air-raid wardens spread the alarm along the |

waterfront to open household and factory

windows—and then stay away from them—

for fear of a devastating explosion. Crews

of fireboats and tugboats risked being blown

sky high, until the ship was towed to a

remote spot and scuttled in water deep

enough to put out the blaze.

Newspapers headlined the spectacular

event. But few knew the behind-the-scenes

story that follows all such marine misad-

ventures. The place to find that out is

“Hydro"—the Navy's Hydrographic Office

at Suitland, Md. which serves as the

Government's clearing house for up-to-the-

minute maritime information.

Advised of the derelict’s position by tele-

type from official New York headquarters,

Hydro relayed details to Washington and

Boston radio stations. Shortly the warning

went crackling through the ether to vessels

at sea on a scheduled “BAMS” program—

“Broadcast to Allied Merchant Ships.” Next

day, substantially the same message ap-

peared in the Hydrographic Office's “Daily

Memorandum.” It read:

“NEW YORK HARBOR, SUNKEN

WRECK, BUOY ESTABLISHED.—Wreck

Lighted Buoy 29A, colored black and show-

ing a quick-flashing light of 20 candlepower,

was established on April 25, 1943, in 45 feet

of water, 1,225 yards 56° from Robbins Reef

Light. The buoy is located about 225 feet

east of a wreck which lies approximately

northwest and southeast with superstructure

showing above water.” For good measure,

the warning also appeared in Hydro's week-

ly “Notice to Mariners,” another of its in-

valuable publications for seafaring men.

Finally, in case there is no immediate

prospect of removal of such a hazard to

navigation, official charts of the area are

stamped with the necessary correction—

which may be a pictorial symbol for a

derelict, a lozenge and a sunburst for a

lighted buoy, and the letters “Qk F1 G” for

quick-flashing green. Newly established

lights and other aids to navigation are in-

serted in similar fashion.

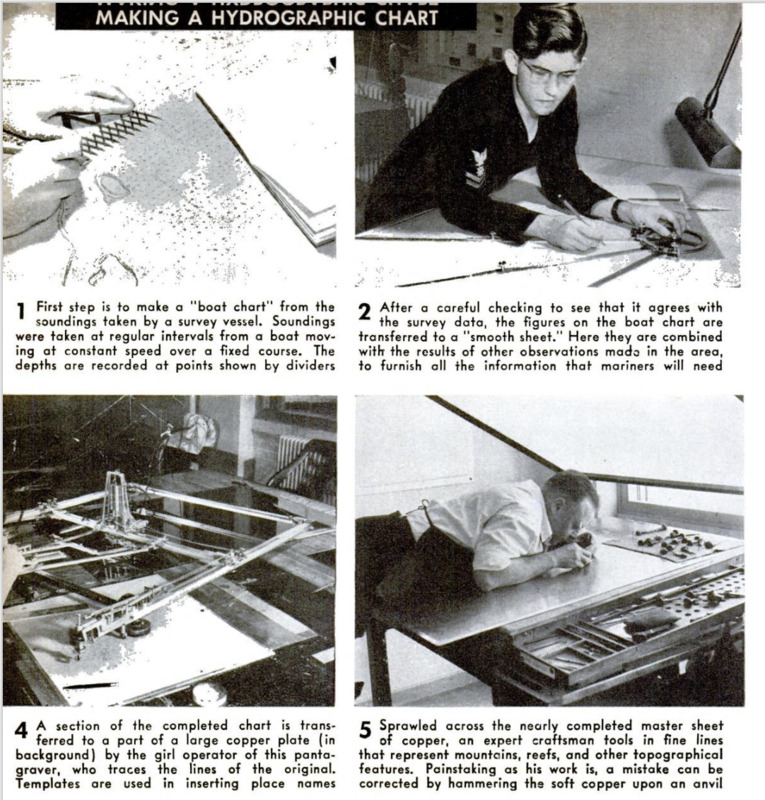

Perhaps this may be getting ahead of

the story. Preparing the original charts

themselves constitutes one of the most re-

sponsible duties of Rear Admiral G. S. Bryan,

Hydrographer of the Navy, and of the

Hydrographic Office which he heads. For

victory in battle and safety in little-known

waters, warships and cargo vessels alike

depend upon the accuracy of these “road

maps of the sea.”

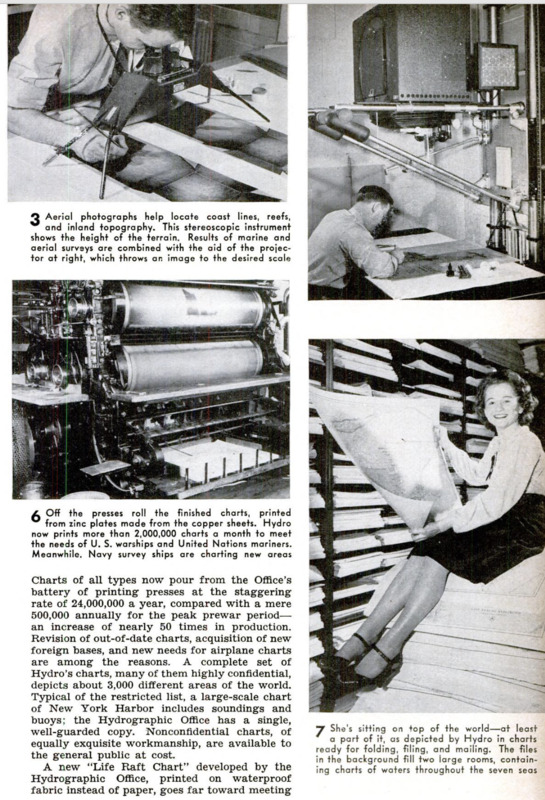

Some idea of war demands upon Hydro

may be taken from newly available figures.

Charts of all types now pour from the Office's

battery of printing presses at the staggering

rate of 24,000,000 a year, compared with a mere

500,000 annually for the peak prewar period—

an increase of nearly 50 times in production.

Revision of out-of-date charts, acquisition of new

foreign bases, and new needs for airplane charts

are among the reasons. A complete set of

Hydro’s charts, many of them highly confidential,

depicts about 3,000 different areas of the world.

Typical of the restricted list, a large-scale chart

of New York Harbor includes soundings and

buoys; the Hydrographic Office has a single,

well-guarded copy. Nonconfidential charts, of

equally exquisite workmanship, are available to

the general public at cost.

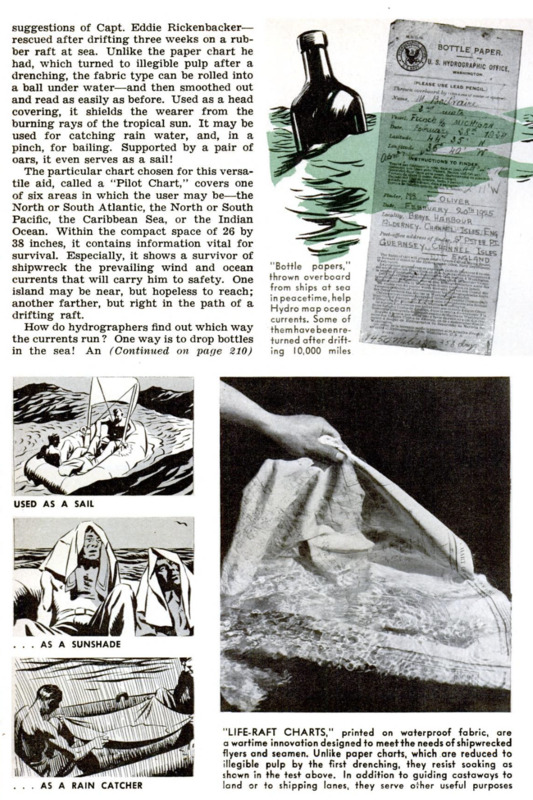

A new “Life Raft Chart” developed by the

Hydrographic Office, printed on waterproof

fabric instead of paper, goes far toward meeting

suggestions of Capt. Eddie Rickenbacker—

rescued after drifting three weeks on a rub-

ber raft at sea. Unlike the paper chart he

had, which turned to illegible pulp after a

drenching, the fabric type can be rolled into

a ball under water—and then smoothed out

and read as easily as before. Used as a head

covering, it shields the wearer from the

burning rays of the tropical sun. It may be

used for catching rain water, and, in a

pinch, for bailing. Supported by a pair of

oars, it even serves as a sail!

The particular chart chosen for this versa-

tile aid, called a “Pilot Chart,” covers one

of six areas in which the user may be—the

North or South Atlantic, the North or South

Pacific, the Caribbean Sea, or the Indian

Ocean. Within the compact space of 26 by

38 inches, it contains information vital for

survival. Especially, it shows a survivor of

shipwreck the prevailing wind and ocean

currents that will carry him to safety. One

island may be near, but hopeless to reach;

another farther, but right in the path of a

drifting raft.

How do hydrographers find out which way

the currents run? One way is to drop bottles

in the sea! An

imaginative youngster, recovering a corked

and message-holding bottle from the surf,

may anticipate finding a romantic message

of shipwreck. But the slip of paper he reads

is headed “BOTTLE PAPER. U. S. Hydro-

graphic Office.” Then follows the name of

the officer who tossed the bottle overboard,

his ship, the date, the latitude, and the

longitude. In eight languages there follows

a request to the finder to add his own name

and address, plus the date and place where

he picked up the bottle, and to return the

slip to the Hydrographic Office or to the

nearest American consul in his country.

Because ships do not care to reveal their

positions in wartime, distribution of “bottle

papers” has ceased for the duration. But

returns are still coming in. Some of the

bottles travel far and long. One bobbed

about in the Pacific until it was more than

10,000 miles from its starting point—and

this is not a record.

In one office, you meet an expert in the

Japanese language. Surrounded by flower-

ornamented dictionaries, he is diligently

“translating” Japanese charts that may be

of service to American warships.

Moonlight charts, showing the brightness

of the moon at various times and locations,

are another reminder of war. They indicate

when darkness will cover a raid on enemy-

held territories.

By the time that the United States en-

tered the war, American pilots were well

acquainted with “Approach and Landing

Charts,” newly developed by Hydro, which

enabled flyers of average skill to make safe

landings in totally unfamiliar and obscure

places.

An improved star finder and identifier,

developed by the Hydrographic Office, eases

the task of aerial navigators, especially when

clouds obscure a part of the night sky. This

outfit includes a star map and a series of

interchangeable scales, each corresponding

to a certain latitude. When the proper scale

is mounted on the map and set according to

the observer's local meridian, the altitude

and azimuth of any visible stars may be

read from the scale markings.

As an indication of the variety of Hydro's

publications, one of the most recent bears

the title, “Eskimo Place Names and Aids to

Conversation.” Standard “Pilots,” supple-

menting nautical charts, give detailed direc-

tions for reaching desired destinations, much

after the fashion of automobile guide books

—except that lighthouses and buoys replace

road forks and railway bridges.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Alden P. Armagnac (writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1943-10

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

97-100, 210

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public Domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Matteo Ridolfi

-

Alberto Bordignon (Supervisor)

Popular Science Monthly, v. 143, n. 4, 1943

Popular Science Monthly, v. 143, n. 4, 1943