-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

"Ghost Planes" Fights On

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

"Ghost Planes" Fights On

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

THE normal life expectancy of an air-

plane design is about four years. Under

normal military operation, a fighting plane

is superseded by types that can outperform

it, as design science strides past yesterday's

milestones. New engines, better propellers,

improved wing sections, and superior ma-

terials make yesterday's winged miracle to-

morrow’s crate. Even in commercial air-

transport design, a four-year-old airplane

type is about ready for the freight runs in

the backwoods.

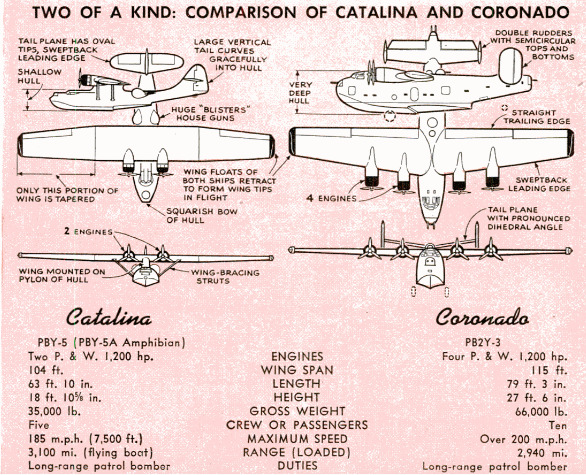

There is one holdout in airplane design: a

Navy-type flying boat that has managed to

survive a full decade and is now ready to

be reordered—the Consolidated PBY-5, the

tough, indestructible Catalina. The latest

dope on the “Cat” comes in an unobtrusive

release from the financial department of

Brewster Aeronautical Corp. Some weeks

ago, this company’s Newark division, which

had been engaged in building wings and tip

floats for the Cat, completed

what was believed to be the

last order for Navy PBY

boats. A new, slick twin-

engined ship with a deep

hull and a swift, high-

aspect-ratio wing was going to take its

place. The old Cat was, at last, going to die.

The idea evoked sighs of mingled nos-

talgia and relief in certain Navy flying

circles. The Cat was a slow, ungainly fly-

ing boat with apparently little to recom-

mend it in a modern war. Before the Sude-

ten occupation, the Navy had released it for

commercial purchase, and even allowed

Consolidated to sell license rights to Soviet

Russia. Now, for all practical purposes, the

Cat was to be allowed to die. Then, with

dramatic suddenness, Brewster announced

that a new contract for Catalina wings and

tip floats had been signed. The Cat had a

new lease on life.

The Catalina’s record in this war is a

glorious one. It began with another re-

prieve, this one by the British. The R.A.F.’s

Coastal Patrol needed a good production-type

flying boat, and needed it quickly. Consoli-

dated Aircraft had a splendid flying boat in

the prototype stage, with primary tooling

already under way. The British, however,

needed immediate deliveries on seaplanes—

needed them desperately, to patrol the sea-

ways around the embattled island. They

decided to forego the airplane of tomorrow

for one they could fly immediately, so the

Cat, which was scheduled for the limbo of

Jennies and Liberty DH's, was put back into

production as a stopgap. She has been fill-

ing the gap ever since.

Despite her lack of speed,

the Cat is among the best

seaboats ever built. Her

hull can stay in the water

for weeks on end, requiring

only cursory service. She waddles through

heavy weather, ever prowling in search of

German and Japanese warcraft. One found

the German battleship Bismarck and hung

on grimly, riddled by gunfire but not

downed, until British forces could be dis-

patched to destroy the Nazi battleship.

Others have torpedoed Japanese war ves-

sels, bombed Kiska hundreds of times, and

helped hold the Nazi submarine menace in

check from bases in Great Britain.

Now, confounding enemy and American

airmen alike, the Cat engages in dive-

bombing sorties, screaming down at the

unheard-of speed of 250 knots. Pilots drop

bombs by the “seaman’s eye” method, then

apply the strength of four arms to pull her

out into level flight.

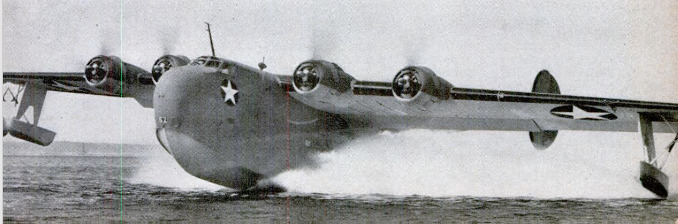

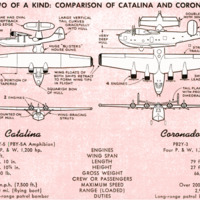

Resting on the beach or in the water, the

Catalina, known by the Navy as the PBY-5

(flying-boat version) ‘and the PBY-5A (am-

phibian) reminds you of those other prewar

oats which have been outmoded by the

sleek craft of 1943. Unlike those other

relics of the past, she can fly over enemy-

infested waters for a total distance of 2,520

miles, starting with 1,463 gallons of gas in

her tanks and loaded with bombs or tor-

pedoes and ammunition for her 50 caliber

guns.

But she can’t reach enemy targets and

escape the withering fire of Zeros and

Heinkels with the sureness of a much faster

and more modern land

bomber. In fact, she

can’t escape at all, ex-

cept by hiding in the

clouds and mist. Her

gunners must man their

weapons and try to out-

shoot enemy attackers,

for a top speed of 185

m.p.h. gives them no

other choice.

Yes, the Cat must

fight to survive. And

somehow, miraculously,

as a breed she continues

to live, snooping through

the Aleutians’ perpetual

mists, night-hawking

over the Southern Pa-

cific to smell out Jap

concentrations, blasting

subs in the Mediter-

ranean and Atlantic, and

bringing back alive many

Yankee pilots, who, shot

into the sea, would oth-

erwise perish.

There were few Cats

in the Aleutians when

the battle for their oc-

cupancy began early in

June, 1942. Losses were heavy as the Navy

brought in more PBY's and threw their

crews into the fight to protect Alaska.

Many winged westward into the murk and

never came back. But their crews per-

formed miracles of bravery. On June 10, a

Cat found the first Japanese ships in Kiska

Harbor. The very next day, another, poking

its blunt snout through snow and rain, re-

ported Japanese landings at Attu.

How many Cats were lost in the Aleu-

tians may not be known for many months,

but the crews never wavered. Pilots of Pa-

trol Wing 4, shortly after Dutch Harbor

was first attacked, began bombing Kiska

as regularly as a clock ticks. For three

days they pasted Kiska through rains of

antiaircraft fire, destroying 65,000 tons of

shipping. One pilot beached his Cat after

reporting briefly, “Ship now land plane.

Hull no longer waterproof.”

The Navy's high command looks upon

these outmoded crates as offensive weapons,

no matter what their limitations. Pilots

and crews know that their very slowness

makes them excellent targets for both anti-

aircraft fire and enemy aerial gunfire. One

fiyer in the South Pacific radioed his com-

mander, “Am shadowing (the enemy).

Notify next of kin.” Ten minutes later he

was dead.

Shortly before dawn on June 3, 1942, En-

sign Jewell Reid, of Paducah, Ky., left Mid-

way on a routine patrol. By midmorning,

his Cat had covered several hundred miles

in a westerly direction, when he sighted on

the horizon several objects he did not im-

mediately identify. Reid swung the ship

about, moved in for a look-see, identified

them as a Jap fleet, reversed his course to

check their direction and speed. Then his

voice spoke into the radio, warning of the

intended attack on Midway. That night a

squadron of other Cats commanded by

Lieut. Gaylord D. Propst, partly protected

by darkness, launched torpedo attacks

against Japanese transports—the first time

these boats ever had been employed as tor-

pedo planes.

I. M. Laddon, vice president of Consoli-

dated Vultee Aircraft Corporation, scarcely

dreamed that these long-range boats would

play major roles in war when he designed

the first of the long line in 1933. He wove

into their metal and fabric qualities of long

range, durability, and comfort, plus capac-

ity for bomb-carrying. Two 800-horsepow-

er engines powered the first boat. Today's

Cats duplicate the prototype, with the ex-

ception of three major changes. A pair of

1,200-horsepower Pratt and Whitneys fitted

with hydromatic propellers haul them sky-

ward now, and two blisters on the sides of

the fuselage give the gunners a chance to

protect themselves against enemy gunfire.

Laddon built well. In 1937 the Navy, of-

ficially recognizing the worth of patrol

planes for scouting purposes, transferred all

scouting-force destroyers to the battle force,

and all patrol-plane squadrons to the scout-

ing force.

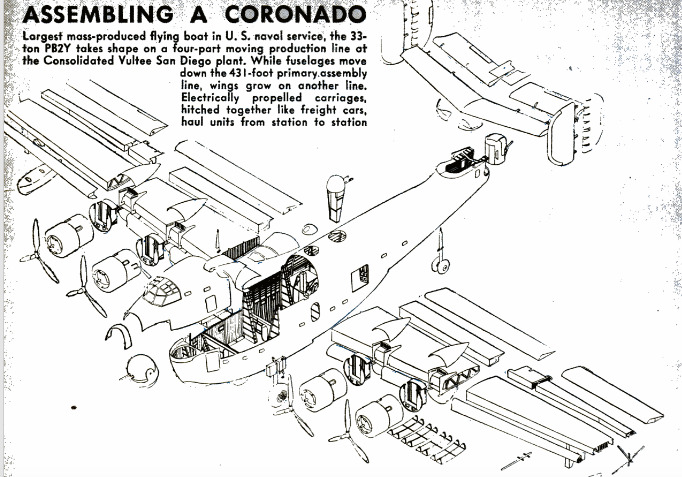

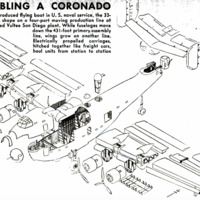

Ten years is a mighty long time in the

life of a plane, and while the Cats promise

to give added years of service, their “big

sister,” the 33-fon Coronado long-range pa-

trol boat, is now in production. These com-

bination aerial battleships and cargo-per-

sonnel carriers take shape on a four-part

moving production line, making them the

largest mass-produced flying boats now in

the U. S. naval service.

Known in the combat version as the

PB2Y-8 and the cargo carrier as PB2Y-3R,

the Coronado can fly long distances on pa-

trol or to carry needed goods to distant

battle areas. Under and in the wings of the

PB2Y-3 may be tucked several bombs andtorpedoes, or a six to eight-ton bomb load.

Up to 5,000 pounds of cargo may be carried

long distances with a heavy gasoline load.

The Coronado is a complex mechanism.

Her crew of ten, living and working in

seven main compartments on three decks,

operate 50 caliber machine guns mounted

in turrets placed in the nose, tail, and amid-

ships; drop their loads of bombs and tor-

pedoes, and prepare their reports while over

the sea. To facilitate take-offs and increase

her speed during flight, the hull has two

steps and a semicircular top, and the all-

metal after step terminates in a vertical

knife edge, which aids the boat in breaking

away from the water and holds it on course

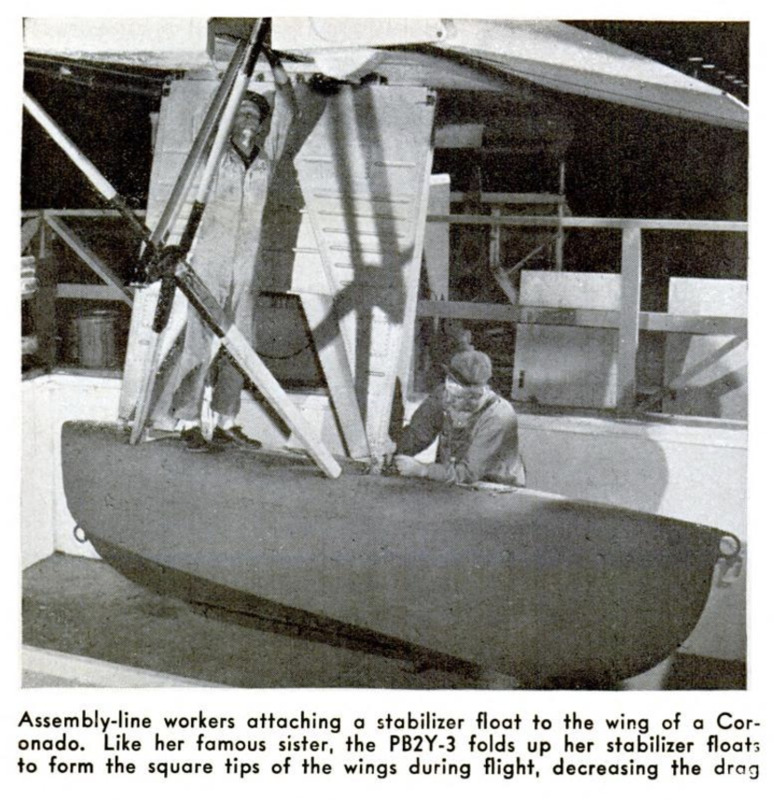

before take-off. As on the Cat, stabilizing

floats retract during flight to form the

square-tipped wings. Twin fins and rudders,

large and set high, and a stub nose make

the boat easily recognizable. The wing

sweeps backward along the leading edge

and carries a ruler-straight trailing edge.

You haven't heard much about these big

boats, because they have been assigned pri-

marily to look and listen and carry big

loads without being trapped by the enemy.

Their names will appear more frequently

in the future, though, for new jobs are con-

stantly being found for the big sisters.

Right now the Navy Department is expand-

ing its Naval Air Transport Service from

three to 10 squadrons. Seven already have

been commissioned. This means more Coro-

nados will join the network which last year

covered. 50,000 miles of routes. A recent

$40,000,000 Congressional appropriation

promises the network will be tripled, with

personnel and cargoes destined for battle

being transported all over the world, from

Australia to Africa, from Iceland to Rio.

Recently another sister boat was an-

nounced. This is the Model 31, to be known

as the P4Y—a twin-engine, long range pa-

trol boat which the Navy considers the fast-

est flying boat ever built in America. Fitted

with the famed Davis wing, which helps

give the B-24 Liberator greater speed and

lift than most bombers her size, the newest

of the Cat family has been designed for

both combat and patrol duty. Carrying a

crew of seven, she is powered by two 2,000-

horsepower engines, measures 74 feet long,

stands 25 feet high, and weighs some

50,000 pounds. When she arrives, the Cats

will take a new lease on life.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Andrew R. Boone (writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1943-10

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

120-124

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public Domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Matteo Ridolfi

-

Alberto Bordignon (Supervisor)

Popular Science Monthly, v. 143, n. 4, 1943

Popular Science Monthly, v. 143, n. 4, 1943