-

Titolo

-

Planes Back Up Ground Forces in Our New Theory of Air Power

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Planes Back Up Ground Forces in Our New Theory of Air Power

-

extracted text

-

ALLIED victory in Africa and again in

Sicily—first steppingstone to the inva-

sion of Europe—was prepared and consum-

mated under the protective web of air power,

superbly co-ordinated with the attacks of

the decisive ground forces and the mainte-

nance of the essential sea lanes.

On one field of battle after another, the

Story was told: Allied heavy bombers plas-

%ering the enemy's rear-area air bases and

supply ports; Allied medium bombers blast-

ing his advanced fighter bases, tank columns,

and infaritry reserves on the roads; Allied

dive and glide and fighter bombers slashing

and strafing at his forward lines and strong

points.

This expert collaboration between air and

ground forces is the fruit of a new theory

and technique in the use of air power. Devel-

oped by both the British and American air

forces, this theory recognizes two basic kinds

of support that air power can give to ground

power. In Africa it found expression in the

division of our air strength into Strategic

and Tactical Air Forces. Its success marks

it as the pattern for the future employment

of the air arm and as one of the most impor-

tant recent developments in the art of war.

Strategic air power, in this technical

sense, is represented mainly by large bomb-

ers, flying relatively long distances to strike

the enemy in his home areas—war indus- |

tries, communications, ammunition depots,

barracks, port facilities, This can be a form |

of air support, as when Maj. Gen. Jimmy

Doolittle’s heavy bombers crippled the Axis |

African air force by bombing out the sup-

port fields in Sicily and Southern Italy. But

it also may function independently, as in |

the strategic bombing of Germany by the |

RAF and the U.S. Eighth Air Force. |

Air support in its purest, most direct

form, is the job of tactical air power. No |

fixed limit is applied on space, although air-

men have a rule of thumb that tactical

operations will not usually penetrate farther |

than 150 miles into the enemy's territory. |

The British called this type of air power

“close support,” although no one has yet

been able to give a satisfactory answer to the |

inevitable question, “How close is close?”

Its main work is the bombing and strafing |

of the enemy at the precise time and place

that will assist infantry or armored troops

to overcome local resistance.

The old notion that air-ground support

was entirely confined to light and dive

bombardment has been completely over-

thrown. Any bomber, up to the giant B-17's |

and B-24's, may be used on a support mis-

sion. As a matter of military economy, how- |

ever, light or medium bombers usually can |

perform an air-support assignment with

greater speed and efficiency. |

Air support can use a fighter plane to

strafe the enemy, a glide or low-level bomb-

er to drop delayed-action bombs on his

columns, a dive bomber to plunk a load of

high explosive on a strong point, a medium

bomber to lay a stick or a salvo of ruin |

across a fortified position, or let down a

string of delayed-action parachute bombs |

in a low-altitude sweep across a troop or

truck concentration. |

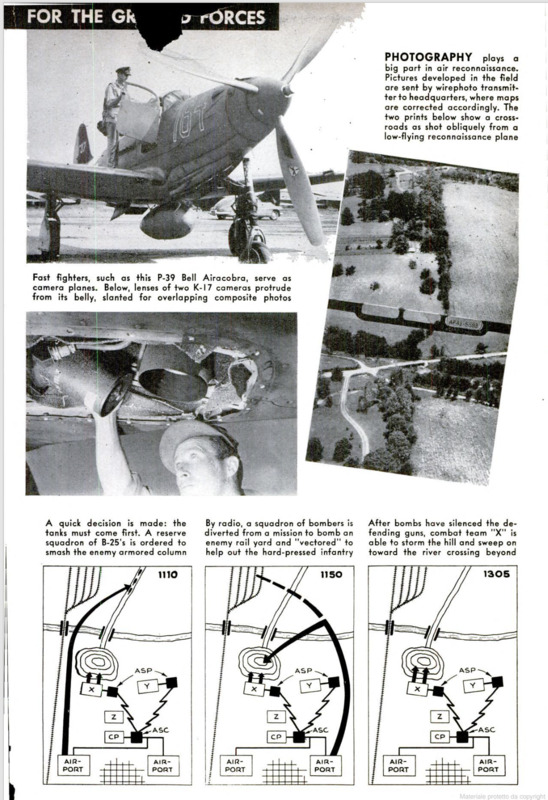

Liaison and reconnaissance planes com- |

plete the list of air equipment used, with all |

types represented from tiny “grasshopper”

planes that can land and take off in open

fields, to converted twin-engined Lightning

fighters that can outpace or outclimb any-

thing the enemy could put in the air. |

Men and planes do the fighting, but the |

lifeblood of their work is communications,

and here again every method is put to use,

from the simple act of waggling a plane's

wings or dropping a message, to the most

highly developed radio and wire equipment. |

Basic communications from headquarters |

to air bases are carried out by teletype

wherever possible. Teletype is unique in

providing both ends with an instantaneous,

permanent copy of the order or message, |

thus cutting the chance of error or mis-

understanding down close to zero. The tele-

phone and radio circuits supplement this,

and radio naturally is invaluable for com-

munication with planes in flight, when plans |

must be altered at the last moment.

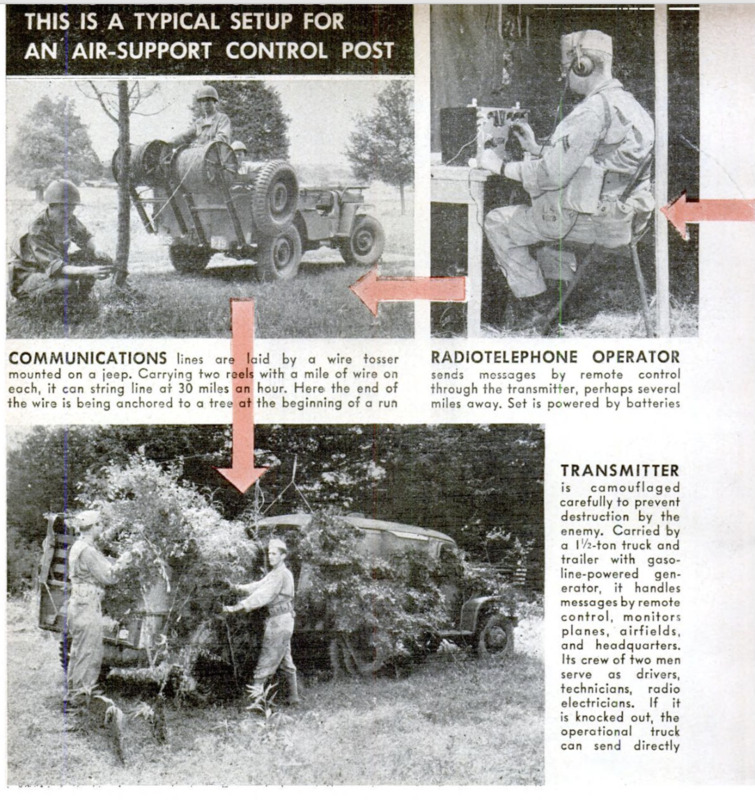

Wire-tossing jeeps that lay phone and

teletype wires at 30 miles an hour help keep

the communications system functioning even |

during periods of rapid movement. Radio |

communication in the field is carried on

mainly through a series of highly ingenious

trailer trucks evolved by the Air Forces.

The trailers carry their own generators, but

tap into power lines where they are avail-

able. If the enemy air force is operating in

strength, wire can be laid and the entire

trailer operation carried on by remote con-

trol, with as much as seven miles between

the broadcasting unit (which might be

spotted by enemy radio direction finders)

and the operational unit which is originating

the messages. If the remote-control truck is

knocked out by enemy bombing or artillery

fire, the operational truck has duplicate send-

ing and receiving equipment to continue

work.

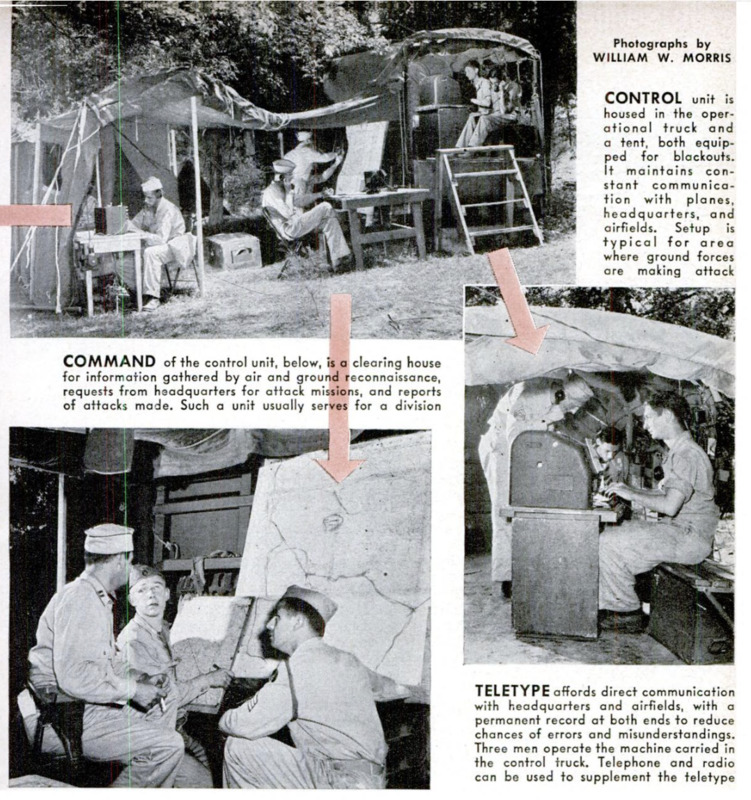

Into these communications centers pours

the endless flood of battle information—re-

quests from headquarters for attack mis-

sions, reports of attacks carried out, and

disposition of enemy units observed by

reconnaissance aircraft.

Liaison between air and ground forces is

effected by the assignment of air officers to

work in co-operation with the g ound com-

manders. An Air Support Command normal-

ly is set up to function with an army or

corps in the field. An Air Support Control

works with a smaller unit, usually a divi-

sion; a typical Control would include three

officers and ten enlisted men with their

communications

equipment. An Air Support party —some-

times a single liaison officer—is attached to

a field unit, such as a regimental combat

team.

These men funnel the inflowing mass of

information, strain out what is important,

pass on what the ground commander should

know, and expedite requests for air support

at specific places and times. Their work

must be cool, unhurried, yet rapid and

precise. The plans they draw up and the

orders they give tell the story.

The complexity of air support, the fluid

brilliance with which it functions in battle,

is almost impossible to visualize without

seeing it in action—and few civilians ever

can have the chance to see it. Even the war

correspondents who get behind the scenes

of military operations are barred by security

regulations from describing the technical

workings of the machine.

To give a clear, dramatic picture of air

support, POPULAR SCIENCE, with the co-

operation of Army Intelligence sources, has

arranged an account of one day's air-ground

operations on a divisional front. It is ac-

curate in every detail, although the descrip-

tion is sufficiently generalized that mo in-

formation can be revealed to the enemy.

The opposing forces are facing each other

along a line lying roughly between the town

of X and Unknown River. Our forces are

attacking to the north, while the enemy,

giving ground slowly, is attempting to hold

south of the river. At dark our troops have

been stalled by stubborn resistance. The

division commander has decided that he

must lean heavily on air support in the

next day's fighting. |

The battle plan is set up at a conference

in the tent of the chief of staff. Attack is to

be resumed in the morning, with Combat

Team X making the main effort on the left.

Team Y will hold the right flank and Team

Z will be held in reserve. The first need is

for thorough air reconnaissance far behind

the enemy line. The second is for heavy air

support, as most of the artillery will have to

be concentrated on a relatively narrow front

in support of Combat Team X.

Air Commander recommends continued

pressure to keep the enemy air force pinned

down, plus a heavy bombardment of key

rail lines. As for the direct support of the

attack, that is a matter of careful timing.

The infantry push is scheduled for 0615,

preceded by a 10-minute artillery barrage

of maximum violence, beginning at 0600.

Air support is to strike at precisely the

interval, hitting at 0610 with a low-level at-

tack by six A-36 Mustang fighter-bombers.

Two minutes later the pounding will be

taken up by another flight of six A-24 dive

bombers.

As an indication of the precision with

which air and ground operations are inte-

grated, the artillery barrage will end with

the firing of smoke shells to mark the ob-

jective for the diving planes; the last dive

bomber gives the infantry the signal to go

ahead by waggling its wings. Our own

front lines will be marked with colored

smoke to obviate any danger of an error in

bombing objectives.

The chief of staff okays these arrange-

ments and orders the necessary reconnais-

sance and photographic air missions to be

worked out with the G-2 (intelligence) of-

ficer. Next comes a conference in the Air

Support Control office, usually located near

the divisional command post. The G-3 (op-

erations) officer explains the plans for

ground operations, while the Air Command-

er outlines his operations to the liaison of-

ficers of the various air groups — recon-

naissance, dive bombers, medium bombers,

and fighter planes.

The complex process of mounting a co-

ordinated air-ground operation moves along

as the air support and divisional signal offi-

cers go into a huddle of their own, check

over their wire and radio communications,

shift some of the radio frequency bands

which are jamming up against powerful

enemy transmitters, and arrange a code of

visual smoke and panel signals. Finally, the

Air Commander is ready to issue his attack

and operations orders, which are teletyped

to the airdromes over the A-2 wire net.

At dawn the attack begins, with a thun-

dering artillery barrage pouring down on

the hill which is the enemy's chief point of

resistance. With split-second timing, at

0610, the artillery fires its smoke shells, the

infantrymen set off red smoke to mark our

advanced lines, and out of the low-hanging

mists roar the A-36 Mustangs, to strike with

their bombs, then vanish. Immediately the

Douglas Dauntless A-24 dive bombers ar-

rive, peel off one by one, and smash at the

target. As the last plane gives the signal

by rocking its wings, the infantry attack is

launched.

While the ground fighting grows in inten-

sity, the planned air operations go ahead

with attacks on enemy air fields and supply

lines. About 10 am. full reconnaissance

reports and air photographs from 30,000 feet

reveal an alarming development. A heavy

enemy striking force, including 100 tanks

and additional armored and supply vehicles,

is moving up on the rear roads, clearly head-

ing for the point of our main attack.

Meanwhile the infantry advance has run

into terrific opposition at the contested hill,

and has been stopped dead in the woods at

the foot of the slope by heavy fire from mor-

tars, machine guns, and 77-mm. field guns.

The infantry commander has learned that

he cannot get any additional artillery sup-

port, and has sent a hurry call for help to

his accompanying Air Support Party of-

ficer, who radios Air Control to ask what

missions might be assigned or diverted to

help pull the situation out.

Here air command has two new and press-

ing problems. The enemy-held hill needs

our attention; so do the approaching tanks.

But ground-force headquarters must deter-

mine the relative priorities involved, and the

division chief of staff unhesitatingly puts

the tank column first. A reserve squadron

of B-25's (North American Mitchell medium

bombers) is ready, and is ordered into ac-

tion through the flexible system of control.

Photo maps and latest reconnaissance

data are hastily assembled, and the crews

file into their field headquarters for brief-

ing—an informal but deadly serious process.

The youthful squadron leader explains cas-

ually that “our doughfoots are in a jam,

and it’s up to us to deliver a low-level at-

tack that will stop a column of enemy

tanks. They're getting too close to a spot

that's already too hot.”

He shows them the map point where they

will take formation, echeloned to the right.

The attack will be pressed home at extreme

low altitude, with intervals of 2,000 feet.

“Give 'em your forward guns on the way

in, and release all bombs in train.” Fighter

escort is arranged with a near-by field. The

combat crews pile into jeeps and trucks

and roll out to their planes, scattered around

the dispersal area.

The tank column, rolling south at 20

miles an hour, is attacked at “zero-plus al-

titude.” The first B-25 sweeps in over the

trees, its guns blazing, and cuts loose with

its bombs, which have delayed-action fuses

set for the planned attacking interval so

that they will explode just after the plane

is out of the way and before the next at-

tacker slashes by.

The formidable armored column disinte-

grates into a wild, scrambling mass of ve-

hicles and men. Within 10 minutes the road

is strewn with burned and blackened equip-

ment, and the pummeled remnants of the

enemy force are withdrawing in total con-

fusion.

Meanwhile, air support is working on the

problem of the enemy hill. No other re-

serve flight is available, so bombers must

be diverted from a planned operation to

take up this emergency job. By means of

radio equipment and a secret technique, the

air support command “vectors” a squadron

of bombers on their way to blast enemy

railroad yards behind the battle, and steers

them to the new target. They wing in,

drop a blanket of destruction on the enemy

strong points and artillery emplacements,

and clear the way for the combat team to

push ahead, carry its objective, and then

drive on to the river crossing against stead-

ily deteriorating resistance in the late after:

noon.

For air operations the day ends with the

return of the planes and systematic inter-

rogation of the crews to determine the re-

sults of their attacks. This is done at the

air fields, where the airmen gather at the

squadron intelligence officer's office, make

themselves comfortable with coffee and

cigarettes, and then answer the long routine

of questions on what targets they hit, what

effect the bombs had, what air opposition

or ground fire they encountered, what the

weather was like, and so on and on.

But the day ends only in the sense that

this information is summarized and re-

ported on to the higher command, which

starts at once to plan the air support for

the next operation—only a few hours away.

This, in capsule form, is how air support

works. And what it means to the ground

forces was best summed up by the Allied

field commander in Tunisia, General Sir

Harold Alexander, in this message to the

African Tactical Air Command:

“Without your support this drive would

just not have been possible.”

-

Autore secondario

-

John H. Walker (writer)

-

William W. Morris (photographer)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1943-11

-

pagine

-

49-52, 202, 204, 208, 210

-

Diritti

-

Public Domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by

-

Matteo Ridolfi

-

Alberto Bordignon (Supervisor)