-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

Jap air force puts new planes in the air

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Title: Jap air force puts new planes in the air

-

Subtitle: Is the enemy preparing secret weapons for a last battle?

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

OUT of three years of air warfare rang-

ing over much of the 63,000,000 square

miles of the Pacific, a new pattern of Japa-

nese defensive tactics is developing. They

bode harder going for the United Nations as

they approach the core of Jap resistance.

For six months after Pearl Harbor, the

Jap airman had things his own way. Then

he began slipping. By mid-1944 his losing

battle on the entire perimeter of his defense

line was assuming the proportions of a

rout. Obviously his air establishment had to

be refurbished if he was to ake a stand.

Today, entering the fourth year of Ameri-

ca's participation in the Asiatic war, we

are encountering bigger, faster, more heavily

armed Japanese aircraft. We are encounter-

ing ingenious devices designed to throw air-

borne broadsides at our heavy bombing

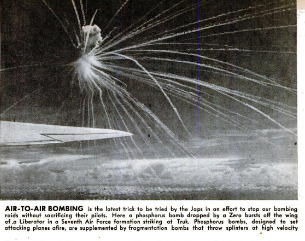

squadrons. Air-to-air bombing, as it is

called, is the newest of the war's anti-

aircraft techniques.

The Jap has only now begun to exhibit the

length and breadth of his resourcefulness as

a last-ditch fighter.

His attempts at air-to-air bombing were

inevitable. His losses in direct fighter as-

saults on our heavily gunned bomber squad-

rons were becoming prohibitive. Interest-

ingly enough, the Japanese atslong last have

begun to conserve their pilot reserve for

the bitter battles to come in China and over

the Japanese homeland.

Unlike the Germans, who experimented

with putting fighter planes in line abreast

and lobbing salvos of rockets at our bomber

formations, the Japs are employing phos-

phorus projectiles in efforts to burn off the

clouds of demolition-laden enemy planes

striking at their industries. These are sup-

plemented with airborne fragmentation

bombs, in clusters, that burst to throw

fragments in all directions at unbelievably

high velocity.

On one mission, a U.S. heavy bombard-

ment group was intercepted by Jap fighters

at about 20,000 feet shortly after the planes

had made their bomb run on the target. A

half dozen passes were made from. nose

and quartering positions. The attacker

came in high, leveled off for his run at 300

feet higher than the bomber, and let go at a

range of 3,300 feet with one or more of ten

66-pound bombs carried under the wing.

The bomb had a three-second time delay.

If the Jap's aim was correct the bomb

detonated at about 800 feet ahead of and

200 feet above his target, since the rate of

closure between bomb and target was 800

feet a second.

The attack was a fair sample of the new

Japanese tactics.

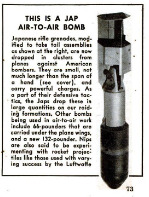

The Japs also are using a new 132-pound

air-to-air bomb and experimenting with

rocket projectiles. Stories are current that

they employ curtains of canisters hung

from wire ribbons attached to parachutes.

The ribbons are of different lengths to

saturate both vertically and horizontally the

portion of the sky that is occupied by an

enemy bomber fleet.

There is little question that the

Japanese are hoarding new types of

extremely fast, heavily armed planes

for the battles to come. Some of

them have been glimpsed briefly on

the outer edge of their air-defense-

in-depth. At least two, perhaps

three, of their fighters are in the

400-mile-an-hour class. For the first

time they have introduced a four-

engine land-based bomber, ostensibly

for assaults on newly won United

Nations bases.

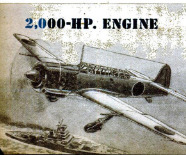

One of their new fighters has an

in-line, liquid-cooled engine, a good

approach to such U. S. types as the

Mustang, the world's fastest. A

long-range Jap reconnaissance plane

has a 2,000-horsepower engine in its

nose. That is only 200 horsepower

less than the highest the United States now uses operationally in a plane.

It is a foregone conclusion that we shall

meet Jap jet-propelled aircraft, inspired by

the German technicians who since Pearl

Harbor have stood behind the Japanese

designer and helped guide his pencil.

Japanese aircraft have gone through a

complete reversal in design trend in the

last few months. In the beginning they

were small, light, lightly armed and with-

out armor plate. They were beautifully

fashioned. They were finished, in fact, much

better than American aircraft. They could

outclimb and outspeed our planes. They

had higher ceilings.

“There T was,” recalled a Wildcat fighter

pilot of the Solomons campaign, “hanging

at 30,000 feet at 90 knots (a bit more than

100 miles an hour) in a ship that was likely

to fall off into a spin at any moment, while

Jap Zeros were doing loops all around me.”

It was simple. The famous Zero, now re-

designed as the Zeke, models 32 and 52,

weighed but 5,500 pounds as against 12,000

10 15,000 for its adversaries. The aluminum-

alloy skin of those early fighters was so

thin that it could be bent between the

fingers.

But Jap design had its weaknesses, and

American fighter pilots took advantage of

them. The moment an American got on a

Jap's tail with a good burst, that thin skin

peeled off like the rind of an orange, or the

fuel tanks, unprotected by self-sealing com-

positions, exploded. Because their planes

were so lightly constructed, most Jap pilots

did not attempt to outdive their foes. They

knew that at high speeds the outsize

ailerons, built into their aircraft to give

high maneuverability, would “freeze

Jap armament was inadequate. Fighter

pilots and the crewmen of bombers were

given the equivalent of our .303 caliber deer

rifle in machine guns, plus 20-millimeter

cannon. Both were of low velocity. Jap

gunners found their targets with .303's

liberally laced with tracers and then opened

up with the cannon.

U.S. planes had nothing less than .50

calibers. One of our fighters mounted a

37-mm. cannon and the rifles on our medium

bombers ran up to 75 mm.

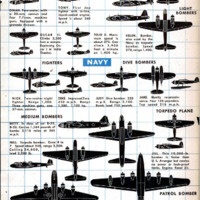

Most of those early Jap planes have dis-

appeared. Here is a gallery of new Jap air

developments:

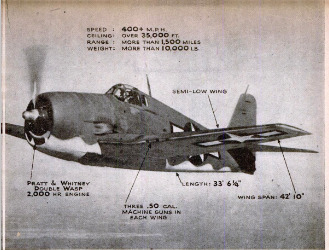

The army fighter Tojo, like all the other

late-day Jap fighters, is

armed with four guns of a

caliber approximating our

.50’s. It carries armor plate

to protect its pilot. It is

less maneuverable, but a

good deal sturdier, than its

forebears. Resembling our

P-47 Republic Thunderbolt,

it has a top speed of 380

miles an hour.

Judy, replacement for the

aging dive bomber Val that

wrought part of the destruc-

tion at Pearl Harbor, has a

top speed well in excess of

that of our standard Navy

dive bomber.

The Dinah Mark II, twin-

engine fighter, performs

spectacularly. It can carry

its crew of two to 10,000

feet in a fraction more thaw

three minutes.

Betty, navy twin-engine

bomber workhorse, incor-

porates a new power-op-

erated gun turret. For |

months, by the way, the

Japs were ahead of us with

bomber nose and tail tur-

rets that could be rotated

360 degrees to permit gun-

ners to cover any angle of

attack, front or rear. |

© The Jap Mitsubishi Kin-

sel radial aircraft engine

has been boosted in horse-

power from a meager 900

to 2,000. As beautifully ma-

chined as anything turned

out in the United States, it

has machine-cut cooling

fins on its cylinder barrels,

a process that succeeded

sand-casting only a short

time ago in this country. |

In engines we have an edge on the Japs.

They are able to draw only a half horse-

power out of each cubic inch of cylinder as

against three quarters of a horsepower ob-

tained by American manufacturers.

Jap adaptations of foreign equipment are.

endless. The U.S.-manufactured Fairchild

aerial camera has been copied, even to the.

model number and the U. S. Navy's inspec-

tion insignia. But in fitting it to their own

uses the Japs improved it by borrowing

a multislot focal-plane shutter curtain |

from the French Gaumont camera, giving

it a wider speed range. They installed a

German cut-film magazine, superior to

American magazines.

The Japs have new radio detection de-

vices, something compare

able to our radar.

Jap tricks, Jap deceits,

are almost innumerable.

, Lately, when a Japanese

reconnaissance plane is at-

tacked and the pilot has to

bail out, he will toss over-

board a parachute-borne

automatic radio sending set

to give his home base a

“fix” on the location of the

attack. :

Japs use U. S. Army Air

“Forces signals and tactics

to confuse their adversaries.

In night assaults they will

switch their lights on and

off in one quarter to dis-

tract attention from a foray

from another quarter. They

use air decoys. On the

ground their camouflage is

nearly perfect. They dis-

pense with tracers in their

antiaircraft fire to hide

their gun positions. They

set traps, such as oil drums

left in the open to invite

strafing.

Up against major-league

opposition for the first time

in his modern military his-

tory, the Jap has learned

quickly. He copied the U.S.

Navy “Thach weave,” a to-

and-fro flying maneuver by

two-plane elements that

protects each pilot from a

surprise attack.

But the Jap is notorious

for mediocrity in pilot ma-

terial and in tactics, and

on those shortcomings we

are capitalizing. The Jap

cannot think when he gets

in a tight situation, for all

his undeniable skill as a pilot.

“I got boxed by a brace of floatplanes,”

related the pilot of an Avenger torpedo

bomber, “but I made a cloud. I stooged

around for a while, and when I came out

the Japs were gone. U. S. Navy pilots

wouldn't do that. They would have hung

around that cloud the rest of the day.”

The Jap's evasive action consists of fitful

turns or diving. The one makes him lose

air speed and frames him for a perfect

target. The other renders him a sitting

duck for the one-two attacks by teams of

American airmen who have learned that

collaboration enables them to live to fight

another day.

Jap pilots have a predilection for sense-

less acrobatics. They cannot make a de-

flection shot—one in which they must com-

pensate for the difference in the angular

courses of their own planes and thir tar-

gets, relative speeds, range and the velocity

and trajectory of their bullets. They waste

an appalling amount of steel trying for

high stern runs, and a direct burst, on

enemy planes. Inexplicable things happen.

A Jap fighter will stand off out of range

and empty its guns and then wheel about

and scoot for home. It bewilders the op-

position but it doesn't help win the war

for Hirohito.

Japs live by the samurai code, which does

not allow them to be captured. Only death

is honorable. Some of the results are weird.

One Jap pilot, told that he must never

leave his plane's operations manual off his

person, bailed out with it and courteously

presented it to his captors. Because he

theoretically could not be captured, he

could not be told what to do if he was.

‘There is little question that we have

killed off or captured the best of the Jap

airmen—apart from those assigned to the

defense of China and the homeland. Jap

air squadrons used to contain four enlisted

pilots to one officer. Now the ratio is six

to one. Only the officers are briefed before

a mission. When a majority of the officers

are shot down, the flight begins to disin-

tegrate.

The Jap mind, architect of a quick war

and a hard peace, has begun to exhibit con-

tradictions in impulse and duty. Often the

Jap airman is anxious to save his own

skin. His interpretation of honorable con-

duct is becoming elastic.

But he is being urged at the same time

to make suicide dives into our bomber

formations,

Col. Kingoro Hashimoto, fiery head of the

central headquarters of the Imperial Rule

Assistance Association, the totalitarian

party, outlined the pattern of attack in a

radio address: “By carrying out a suicidal

crash against our objective, shall we not

sink a battleship with a single plane, and ,

shall we not force down a plane carrying

ten men with a single plane?”

Radio Tokyo reports the use by the Jap-

anese air force of a new suicide plane—

“a V-1 with a pilot.” With its weakness for

embroidering, Tokyo said the planes were

in the hands of a “special attack corps,”

composed of youths of 18 to 20 who were

supplied with only enough fuel to reach

their targets.

The Japs aren't whistling in the dark.

They know that they equal us in many re-

spects, and excel us in some.

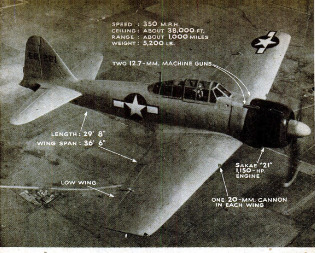

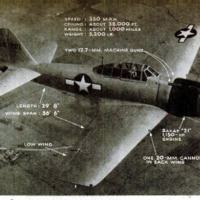

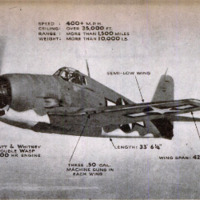

The Zeke 52 and the U.S. Navy Hellcat

are equal in range—about 1,500 miles—but

the Zeke remains more maneuverable, if less

speedy. Jap medium bombers are not to be

sniffed at. The Betty can fly 3,200 miles

without refueling. Emily, four-engine fly-

ing boat, has a top speed of almost 100

miles greater than our Consolidated Coro-

nado, despite the fact that it weighs more

and has a nine-foot-greater wing span.

The Jill torpedo bomber has a speed of

310 miles an hour, as against our Avengers

250 plus. Frank I, a fighter, can do more

than 400 miles an hour and has a range of

1,700 miles. Jack II, another fighter, is

rated at about 400 m.p.h. and has a range

of about 1,100 miles. Frances, medium

bomber, has a top speed of about 350 miles

an hour and a maximum range of 2,800

miles.

The Dinah II, army reconnaissance and

light bomber manufactured by Mitsubishi,

has a modern two-speed engine supercharg-

er, can fly at a top speed of 360 miles an

hour, and has a range of about 1,700 miles.

The Japs’ flush riveting, designed to

create cleaner wing surfaces, compares

favorably with ours. The skin on the first

Zekes was found to be better than anything

we had produced up to that time. It enabled

the enemy to use lighter supporting struc-

tures in the fuselage and wings.

Japanese aircraft designs are suited to

quantity production. Tail sections are built

in separate plants and joined to the fuselage

at final-assembly stations. The quality of

their aircraft instruments is good. In some,

it is superlative.

While the Japanese copied freely from us

in the development of hydraulically oper-

ated “variable-pitch propellers, they have

supplemented them with electric propellers

borrowed from the French and improved.

Japanese aeronautical research is good.

It probably is a fair statement to say that

it is not as good as ours. Their inability

to produce a good self-sealing fuel tank is

proof of it. They enclose their tanks with

layers of rubber, and in some cases with

layers of kapok, but a solid burst’ will still

make sieves of them.

Jap aircraft manufacture of Jate has

emphasized the production of high-perform-

ance interceptor fighters. The enemy knows

what is coming. The vulnerability of their

cities to incendiaries has been established.

Nagasaki burned quite satisfactorily when

incendiary clusters fell on it from the

capacious bellies of our Superfortresses.

Fires set in Tokyo rage for hours after

the B-20's turn for home. The Jap home-

defense command is moving millions of

residents front 11 big population centers in

anticipation of the expansion of the Ameri-

can air assaults.

On the evening of the day of Pearl Har-

bor, a too-glib American radio commentator

asked: “What are the Japs trying to do,

commit national suicide?"

He was four or five years too early, but

he was right. Barring extraordinary po-

litical developments, Japan will die fighting.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

B. G. Seielstad (article writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1945-01

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

67-73,234,238

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public Domain (Google Digitized)

-

References (Dublin Core)

-

B17

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Sami Akbiyik

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Popular Science Monthly, v. 146, n. 1, 1945

Popular Science Monthly, v. 146, n. 1, 1945

Ekran Resmi 2022-07-19 12.08.35.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-07-19 12.08.35.png Ekran Resmi 2022-07-19 12.36.38.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-07-19 12.36.38.png Ekran Resmi 2022-07-19 12.36.46.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-07-19 12.36.46.png Ekran Resmi 2022-07-19 12.36.55.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-07-19 12.36.55.png Ekran Resmi 2022-07-19 12.37.03.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-07-19 12.37.03.png Ekran Resmi 2022-07-19 12.37.12.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-07-19 12.37.12.png Ekran Resmi 2022-07-19 12.37.20.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-07-19 12.37.20.png Ekran Resmi 2022-07-19 12.37.28.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-07-19 12.37.28.png Ekran Resmi 2022-07-19 12.37.34.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-07-19 12.37.34.png Ekran Resmi 2022-07-19 12.37.41.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-07-19 12.37.41.png Ekran Resmi 2022-07-19 12.37.50.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-07-19 12.37.50.png Ekran Resmi 2022-07-19 12.37.59.png

Ekran Resmi 2022-07-19 12.37.59.png