-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

Death for tops filies at fifty feet

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

Death for tops filies at fifty feet

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

AT THE end of its sector, a lone Navy

search plane turned away from home.

For six hours the pilot had flown his Lib-

erator over a huge, empty, and beautifully

‘monotonous pie-slice of ocean trying to find

any Japanese movement by submarine, sur-

face craft, or plane. With Eniwetok, then

the most forward American base in the cen-

tral Pacific, as the apex, the pilot was near

Truk at the end of the pie slice. Instead of

searching the short leg and returning to

base, he flew on toward the great Japanese

bastion.

A hundred miles out, the pilot shoved the

big Liberator down to 50 feet altitude. At

50 miles out, he took it on down to 20 feet.

(The tail gunner said flying fish were going

over his head.). Ini the moonlit darkness the

reef surrounding Truk's lagoon flashed

briefly and the plane was inside the lagoon.

Bow gunner, top-turret gunner, belly gun-

ner, tail gunner, and

the two waist gun-

ners were at battle

stations. The radio-

man on the catwalk

in the bomb bay was

ready to hold the

bomb-bay doors open

in case anything failed

to function. Ahead

and to the south the

hump of Moen, the

largest of Truk's

islands, loomed up,

while directly ahead

little Fanuela Island

rushed at them, swept

below. A mile past

Fanuela, a Japanese

destroyer lay at an-

chor.

‘There were no signs

of the Japs having

been alerted. The

pilot, Comdr. Norman

M. Miller, USN, came

up to 200 feet altitude

and increased his

manifold pressure un-

til he was making

200 miles per hour,

indicated. But the

Japs began to wake.

Searchlights probed

the sky, and the Lib-

erator's crew could

see the yellow-and-

white flashes of the

AA on the shores of

the islands.

Commander Miller

settled into a bomb-

ing run as the de-

stroyer blazed with

antiaircraft fire. The

glare of the guns and

the glare of the bursts

blinded him a little,

ruining his night vi-

sion, and he lowered

his head, watching

his altimeter (200

feet) and his air-

speed meter (200

miles per hour). At

the last second he

looked out again at

the destroyer, now

clearly silhouetted by

its own gunfire, Hold-

ing the bomb-release

button—the “pickle”

—in his right hand,

he waited to squeeze

it until his improvised bombsight told him

he couldn't miss.

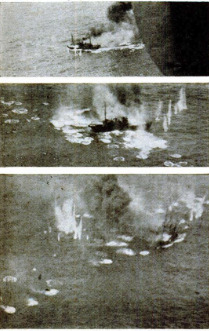

The radioman in the bomb bay saw two

1,000-pounders go down, a fraction of a

second apart. The port quarter of the de-

stroyer flashed under, then the long stretch

of the deck, then the starboard bow. The

first bomb hit with a mushroom on the

quarter, the next close on the bow. The

tail gunner watched the mushrooms blos-

som, watched the destroyer lift itself from

the water and fall back. That was all he

saw, for the night suddenly turned to a

hard glare as two searchlights caught full

on the Plexiglas dome in which he sat.

Commander Miller was fighting the jolt-

ing blows of the flak explosions. Two

searchlights on Moen Island held his plane

like a fly impaled on a pin. The altitude

was still 200 feet, for the pilot could not

make any radical maneuvers without fly-

ing the plane into the water. To pull her

up would kill his speed and throw the whole

belly of the plane into the lights for the

guns which were hammering away from

all the positions in range. He eased the big

plane in a gentle turn to the left, away

from the guns. The lights followed him

and the yellow flashes crept to the left.

‘Then he jammed it hard around to the right,

the long wing tipping steeply toward the

water. The Liberator broke out of the grip

of the searchlights and into the welcome

security of darkness.

The searchlights seemed confused and

circled far to the right of the plane. In-

stead of streaking for home, Commander

Miller turned and headed back toward the

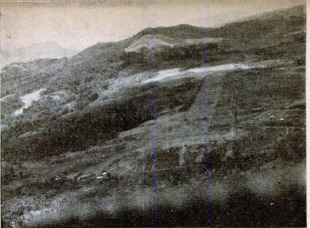

airfield on Eten Island. “I'm going down

the runway,” he said to his crew. “Let ‘em

have it!” They went down the runway at

50 feet. Everything that could shoot in his

plane was going full blast and the plane

felt like the inside of a riveting gun. From

the end of the runway they turned again

and flew over the seaplane base, listening

to the tail gunner tallying the damage to

small ships and tenders going up in flames

as the .50 calibers chewed into them. Com-

mander Miller turned again and crossed the

narrow water to Moen Island, racing down

is airstrip with all his guns spraying

everything in sight.

The bombs were all gone and the gun

barrels burned out. The navigator told him

he had been inside Truk’s lagoon for 18

minutes. Commander Miller had one depth

charge left for use against anything he

might find on the way home, and, down at

20 feet again, he gunned the plane over the

white line of the barrier reef and headed

back to complete the outer leg of his search

sector. The Japanese Navy was minus one

destroyer —and that at the very time

when it couldn't afford to lose a rowboat.

Comdr. Norman M. (Bus) Miller, USN,

was commanding officer and pacesetter of

Bombing Squadron 109—a squadron famous

throughout the Pacific for its succession of

daring low-level attacks and its unheard-of

- record of destruction of enemy shipping and

shore installations. This attack could have

been made by any one of his 20 patrol-

plane commanders at any Japanese base in

the central Pacific, for, in 7% months, the

great planes of VB-100, flying singly and

alone, cut a path ahead of our forces

through the Gilberts and Marshalls, the

Carolines, the Marianas, to -the Bonins,

Kazans, and Volcanos within 500 miles of

Japan itself. .

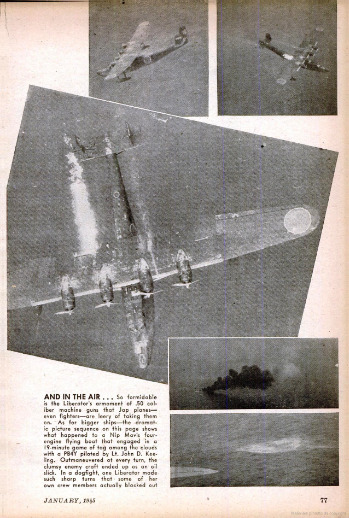

VB-109 was a Liberator squadron. The

Liberator, of course, was designed as a

high-altitude bomber for the Army, and for

best operation at altitudes above 20,000 feet.

At 200 feet it is clumsy, slow, and fairly

unmaneuverable, well meriting its half-de-

risive nickname “boxcar,” but the Navy

needed its range. Known as the PB4Y to

the Navy, the Liberator may carry up to

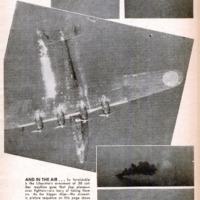

three-ton bomb loads, and it is armed with

enough .50 caliber machine guns to make

‘Jap fighters very cautious about coming

in. At low altitudes the PB4Y's have no

blind spots, and VB-109 never flew them

high.

With the Mariners and Coronados and

Catalinas, the Navy Liberators are the

Navy's “1,000-mile eyes” and their jéb is

search, patrol, and armed reconnaissance.

They fiy a lonely course for hundreds of

miles out from their Pacific base and then

back again, covering every wave in a great

watery triangle of ocean. Every day eight

of the. big planes go out, each manned by

a pilot and copilot, navigator, two radio-

men, and six gunners. A thousand miles

ahead of our forces, they have a look for

Jap shipping and keep an eye on what's

golng on.

Their orders are to attack submarines

and small enemy vessels in their area, to

track and report the movements of larger

enemy shipping, and occasionally to recon-

noiter enemy-held islands and find out what

the Japs are up to. Anything beyond fol-

lowing these orders is extra duty and can

be undertaken on the individual pilot's

initiative only if it doesn't interfere with

the main job of search and patrol.

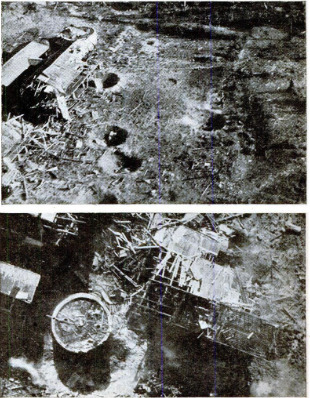

VB-109 flew more than its full share of

the routin patrols, and, in addition to its

regular duty, flew out of its assigned areas

to make 352 attacks on enemy-held islands

and bases. And, rather than track and re-

port, it attacked every enemy ship it could

find on these forays, One hundred and thirty-

four Japanese

naval and merchant ships were sunk or

crippled in masthead-height attacks, includ-

ing a light cruiser, three destroyers, two

DE's and a 10,000-ton tanker. The squadron

never kept track of the barges, sampans,

landing ships, and sailing vessels it sent to

the bottom as the pilots ranged far beyond

their sectors to attack and destroy, sinking

ships in the best-protected harbors.

‘These attacks were made by single planes

flying alone, and all these attacks were

made at low level—50 to 200 feet altitude.

A very large number of them were made

at night. Commander Miller and his pilots

believe thoroughly in the lethal effectiveness

of low-level bombing, and the squadron

trained from the start largely in masthead-

bombing tactics alone. Two hundred feet

was the standard bombing altitude and 200

miles per hour indicated the speed. With

a_delayed-action bomb the plane is clear

of the bomb blast when it explodes and

ready to get back down on the water and

streak for home. And, at masthead height,

it is almost impossible to miss with your

bombs. What is missed can be pretty com-

pletely demolished by the plane's machine

guns. The pilot of a PB4Y does his own

bombing and the pilots of VB-109 devised

a bombsight that worked better than all

tie mechanisms so far invented.

‘There is such a long nose on the Liberator

that the pilot can't see anything below.

The target is under the nose when the

bombs go. But, by constant practice against

land and water targets with real bombs,

the boys learned to drop their bombs When

a two-inch-long piece of masking tape stuck

to the windshield, the “V” made by the port

pilot tube and the nose of the plane, and

the waterline of a ship were all lined up.

With experience, the bombs just don't miss.

Low bombing has been generally con-

sidered the toughest of assignments, but

these boys preferred it. They felt safer

doing it and actually came to fear the few

times when they were required to bomb

from higher altitudes. In all their single-

plane, low-level attacks, not a plane of the

squadron was lost and only one man was

killed by flak in 7 1/2 months.

Much of the success and safety of these

low attacks is explained by the fact that

they nearly always caught the Japs off

guard. The Japs never detected the attack-

ing plane coming in so low until it was in

plain sight—much too late to deflect the

AA guns and bracket the plane. The boys

came in to a target right on the deck—20

to 50 feet off the water—and stayed on the

deck until the last possible second before

pulling up to 200 feet to bomb.

On some occasions, there was time for

a second run before the enemy caught his

breath. The Japs do not sleep by their guns,

and, although they'd be firing on the second

run, their guns would not yet be directly

trained on the plane. Third runs were

never made; by then the Japs were ready.

Of course, the planes were sometimes

hit by flak. Engines were hit and planes

were holed, but they always came back—

and with the crew safe. Even with no time

to train guns on a low-flying plane, the

enemy pumps a curtain of fire straight up,

and, flying through such a hail of bullets

and explosive projectiles in your big target,

you are bound to be hit. Lt. Joseph H. Jobe,

USNR, of Goldendale, Wash., came back

750 miles from the Bonins to Saipan on

three engines one night with his bow and

belly turrets shot away and a fire in his

waist hatch from rupturing ammunition

and exploding oxygen bottles, and landed

safely in the rain on an unlighted field de-

spite a blown tire. And Lt. Comdr. John F.

Bundy, USN, of Sioux City, Towa, brought

his riddled plane from the Kazans safely

back to Saipan after an engine was shot out

at 50 feet altitude on a night-bombing run

across Iwo Jima. But flak in such a sur-

prise attack is never the terror it is for

bombers at altitude when the enemy can

detect their approach from afar and merely

walt for the range to close.

Antiaircraft fire from ships was more ac-

curate and intense than that from shore

bases, the Japs needing so desperately to

preserve their ships and with them the thin

line of supply to what remains of their far-

flung empire. But the aggressiveness en-

couraged in the squadron, and the pilots’

confidence in their own low-level tactics, led

them in against the most overpowering

naval antiaircraft fire. Commander Miller

entered Truk lagoon nine times alone at

night searching for shipping, sinking a de-

stroyer and a 10,000-ton tanker on separate

trips, and one night kicking a light cruiser

around 90 degrees and laying it on its side,

its keel exposed. Lieutenant Jobe blew the

stern off a destroyer at Chichi Jima. Lt.

Comdr. George L. Hicks, USNR, of Three

Rivers, Calif., executive officer of the squad-

ron, jumped an 11-ship convoy between

Guam and Truk—away off the beaten path

—at night shortly before the Marinas nva-

sion, There were three large merchant

ships, seven gunboats, and a destroyer. Bor-

ing in at masthead height through a deadly

screen of protective AA. fire, he blew up

precious 7000-ton merchant ship with his

bombs and set. the other two aire. Before.

Heading for base he managed to damage

three of the gunboats and silence the AA

fire on the destroyer. The next night in

the same area Li Thomas R. Wheaton,

USNR, of Independence, Mo, took on 8

nine-ship convoy. single-handed, sinking a

gunboat, crippling a second, and damaging

a third. Lt. Wiliam B. Bridgeman, USNR,

of Pasadena, Clif, nearly blew himself |

out of the air when he laid his bombs across

the deck of a medium-sized merchant ship

off Ponape, Instead of Felting the usual |

lite" from the bombs ‘bursting behind,

Licutenant Bridgeman's plane was violently

catapaulted forward and nearly somer.

sulted. Flames towered high above the

plane. He had hit an ammunition ship.

Enemy planes were not often willing to

mix it up with the low-fiying Liberators,

although Japanese pilots varied greatly in

degree of aggressiveness. Occasionally sev.

eral Zekes and Tonys made concerted at-

tacks, but the boys simply sat down on

the water and jinked toward home. No |

squadron plane was damaged by enemy

planes, bul several Nips who came in too

close were knocked down or sent smoking

back to base. Li. Comar, William Janeabek, |

USN, of Port Washington, Wis, shot down

a jap torpedo bomber, Kate, one afternoon

ten miles off Truk in an encounter lasting

a minute and & half. On two occasions

pilots deliberately attacked enemy fighters.

Lt. Oden E. Sheppard, USNR, of Bozeman,

Mont, jumped a new twin-engine fighter

and reconnaissance plane, Irving, and sent

it limping home, and Lt. Harold E. Belew,

USNR, of Fresno, Calif, boldly attacked

second one a few days later. |

Bombing Squadron 109 came back to the

States in September for reorganization and

rest, with the best record of destruction

against the enemy of any land-based Navy

search unit in the Pacific. Soon they will

head back for another tour of combat duty,

and they will continue to do just what they

did before—fly day and night and far in

excess of their assigned missions hunting

for the enemy. They will come in on him

singly at treetop and masthead height,

where they can see what they hit and what

happens to it. They like it low.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Ted Steele (Article Writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1945-01

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

74-77,212,216,218

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public Domain (Google Digitized)

-

References (Dublin Core)

-

B-24

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Sami Akbiyik

-

Marco Bortolami (editor)

Popular Science Monthly, v. 146, n. 1, 1945

Popular Science Monthly, v. 146, n. 1, 1945