Il sommergibile ebbe un impatto significativo sulle due guerre mondiali.

I tedeschi furono i primi a comprenderne il potenziale, utilizzandolo già dal 1915 per attaccare non solo le navi da guerra nemiche, ma anche le imbarcazioni mercantili che trasportavano rifornimenti agli Alleati. La guerra sottomarina permise inoltre, per un certo periodo, alle Potenze Centrali di contrastare il blocco navale imposto dalla Marina britannica [Halpern, 1994].

Tuttavia, durante il primo conflitto non vi furono battaglie navali decisive e il principale teatro di guerra rimase sempre la terraferma. La guerra navale riuscì comunque a stimolare l’immaginazione tecnologica dell’epoca. Questo interesse fu particolarmente sentito negli Stati Uniti anche a causa dei fatti legati al Lusitania, un transatlantico britannico affondato da un sottomarino tedesco nel 1915 mentre trasportava più di mille passeggeri, molti dei quali cittadini americani.

Sfogliando alcune riviste scientifiche americane pubblicate negli anni del conflitto, noteremo quindi che numerosi articoli trattano di tecnologie legate alla guerra navale e ai sottomarini. Troviamo inoltre non solo la descrizione di equipaggiamenti e armi realmente impiegati nei mari europei, ma anche dispositivi immaginari, molti dei quali concepiti dai lettori stessi. Ci concentreremo ora su questi ultimi, prendendo in considerazione alcuni esempi tratti da numeri di Popular Mechanics e The Electrical Experimenter, che possono essere utili anche per comprendere come la Grande Guerra veniva raccontata al pubblico di queste riviste.

I sommergibili dei primi del Novecento navigavano per lo più in superficie, immergendosi solo quando avvistavano un nemico da attaccare. Erano infatti spinti sott’acqua da batterie caricate dai motori diesel mentre si trovavano in superficie. I motori non erano progettati per funzionare nelle profondità marine e ciò costringeva i sommergibili a rimanere sostanzialmente immobili durante l’immersione [Friedman, 2014]. Questi mezzi erano quindi destinati ad agire con furtività e silenzio, se volevano cogliere le occasioni per affondare le navi nemiche.

Risolvere il problema del sommergibile

Tuttavia, vi erano due elementi che rischiavano di compromettere i sommergibili rivelandone la posizione. Avevano idrofoni, ma non erano in grado di attaccare basandosi solo sul rilevamento acustico: per questo il periscopio era essenziale. L’altro problema riguardava i siluri. Quelli impiegati durante la Prima guerra mondiale erano spinti da aria compressa, il che lasciava sempre una scia visibile [Friedman, 2014]. Se un transatlantico si accorgeva in tempo di essere nel mirino di un sommergibile, poteva quindi tentare la fuga…

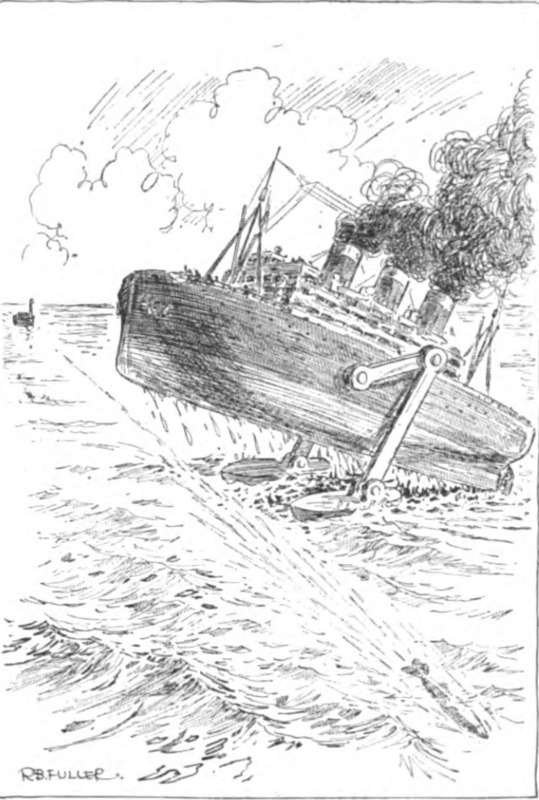

Magari evitando un siluro nemico con un balzo, grazie a gambe meccaniche montate sullo scafo. Si sperava che questo dispositivo, descritto in un’illustrazione pubblicata su Popular Mechanics nel 1918, potesse così risolvere il problema dei sommergibili.

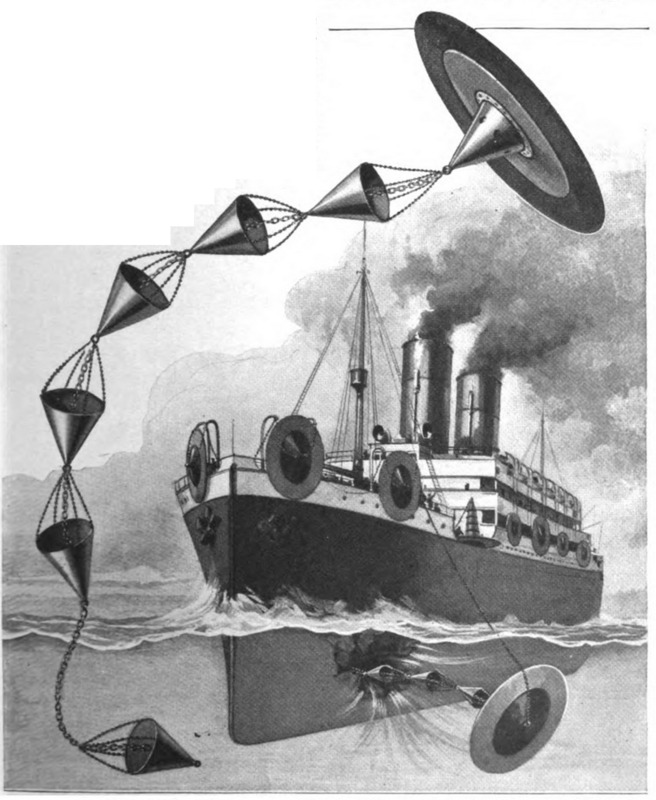

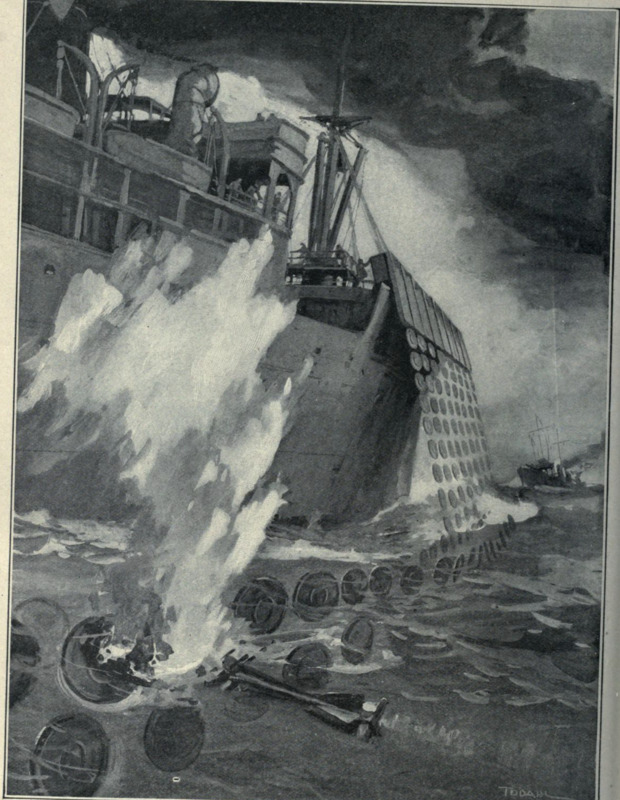

Se la nave non fosse riuscita a spostarsi prontamente e fosse stata colpita da un missile, avrebbe potuto ricorrere a un’altra invenzione immaginata: un disco metallico con una guarnizione in gomma in grado di bloccare la falla nello scafo. Secondo il progetto, illustrato in un altro numero della stessa rivista, la parte interna del disco doveva essere collegata a una serie di secchi di gomma a forma conica che, una volta collocati in mare nei pressi dell’apertura, si sarebbero riempiti e sarebbero stati spinti dal flusso dell’acqua verso il foro, trascinando con sé il disco metallico. Quest’ultimo sarebbe stato mantenuto in posizione dalla pressione dell’acqua contro lo scafo, chiudendo ermeticamente la perdita e permettendo alla nave di restare a galla e rientrare in porto in sicurezza.

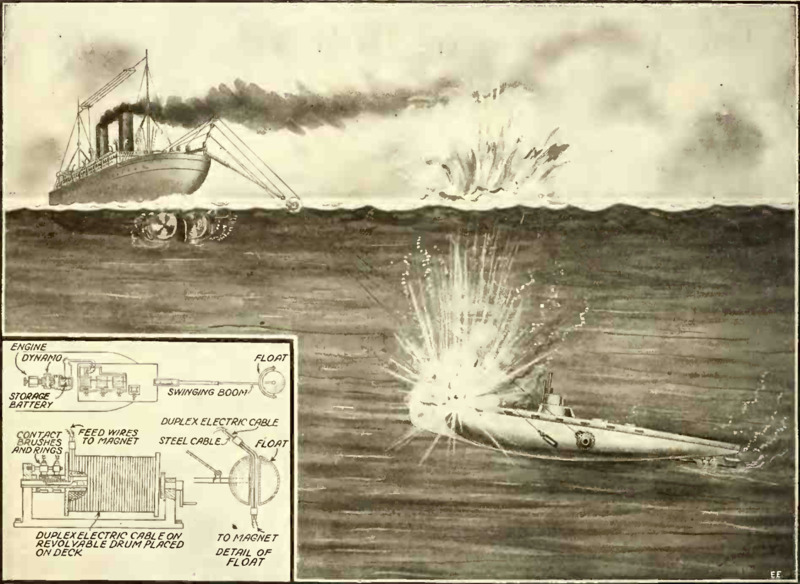

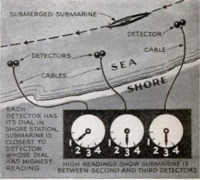

E se una nave, avvistato un sottomarino nemico, avesse voluto attaccarlo e distruggerlo? Una possibile risposta venne presentata su «The Electrical Experimenter». Il piano prevedeva l’uso di un elettromagnete trainato dalla nave mediante un cavo e alimentato da un generatore. Una volta in prossimità immediata di un oggetto metallico, come un sottomarino o una mina di profondità, l’elettromagnete vi sarebbe stato attratto, consentendo così all’equipaggio della nave di localizzarlo. A quel punto non sarebbe rimasto altro da fare che sganciare una bomba per eliminare definitivamente la minaccia.

Un metodo frequentemente suggerito da inventori e divulgatori per la protezione dai sommergibili fu quello di circondare le navi con reti metalliche, montate di modo che navigassero a distanza dallo scafo. I siluri in arrivo sarebbero così esplosi sulla rete, limitando i danni al vascello. Una versione futuristica e mai realizzata di questa tecnologia prevedeva che, alla vista del siluro in avvicinamento, dovessero essere sparati in acqua dei dischi di acciaio rotanti. La rotazione avrebbe fatto sì che i dischi si mantenessero in posizione verticale, e così nell’acqua si sarebbe formata “una grande distesa di dischi rotanti, formidabile come una parete d’acciaio. Colpendo uno dei dischi, il siluro esploderà. Questo è tutto. I venticinque piedi di oceano tra il siluro e la nave fungeranno da cuscinetto, in modo che la nave non subisca danni” (“Popular Science”, 1917).

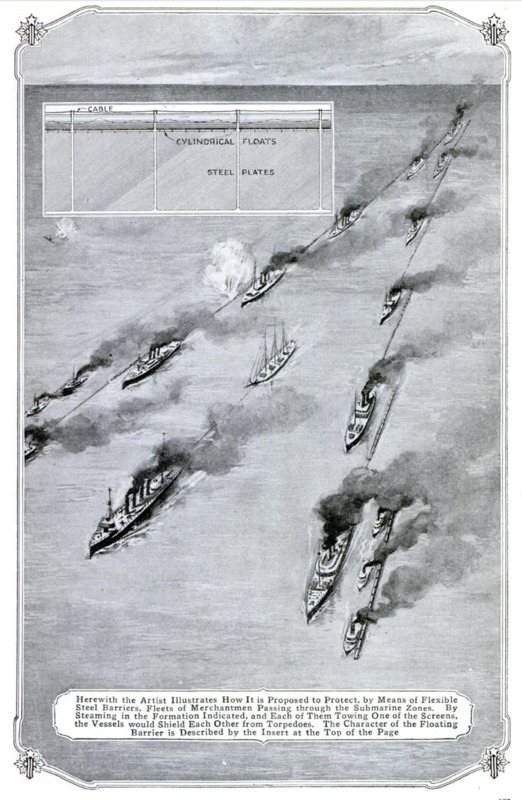

Per difendere i convogli si arrivò anche a proporre l’utilizzo di particolari barriere metalliche flessibili che avrebbero protetto la flotta dai siluri nemici. Le navi avrebbero potuto viaggiare in una formazione sfalsata che avrebbe permesso all’imbarcazione precedente di trainare la barriera di quella successiva e così via, mentre la barriera della prima sarebbe stata trasportata da appositi rimorchiatori. “Nelle attuali condizioni – veniva riportato su “Popular Mechanics” (1917) – il piano verrebbe utilizzato solo nelle zone sottomarine ma, se necessario, le navi potrebbero essere trasportate lungo tutto il tragitto dal porto di partenza a quello di destinazione”.

Inoltre, se un’imbarcazione fosse stata colpita era sempre possibile chiudere la falla. Nello specifico, il dispositivo consisteva in un disco in acciaio laminato, al cui centro sarebbe stata fissata una serie di “secchi conici” in tela gommata. Sarebbe bastato calare in mare il primo di questi “secchi conici”, che – spinto dall’acqua dentro al vascello portandosi dietro tutta la catena fino al disco – si sarebbe posto a copertura della falla e sarebbe rimasto lì fermo sullo scafo grazie alla pressione dell’acqua. “Così rattoppata – veniva riportato nel relativo articolo di “Popular Mechanics” (1918) – una nave avrebbe potuto rimanere a galla indefinitamente e in molti casi raggiungere il porto senza aiuti”.

Queste tecnologie avrebbero dovuto difendere le navi, ma furono proposte anche soluzioni più offensive, volte a permettere di localizzare i sottomarini e procedere alla loro distruzione.

Si pensi, per esempio, all’idea - riportata su “Electrical Experimenter” (1918) - di emettere dei fasci di luce dalla carena della nave che permettessero all’equipaggio di vedere il passaggio di un sommergibile sotto di essa e di rilasciare mine di profondità magnetiche, per attaccarsi al bersaglio, e a tempo, per permettere alla nave di allontanarsi prima dell’esplosione. Ma anche alla possibilità – che nella stessa rivista (1917) si riportava avesse “fatto un’impressione favorevole sugli esperti della Marina” – di diffondere un forte raggio di luce rossa dalla parte sommersa dello scafo, che sarebbe stato monitorato da un osservatore pronto a segnalare eventuali discontinuità nel fascio luminoso dovute alla presenza di sottomarini. I cannoni avrebbero avuto quindi il compito di finire il lavoro. Un’ulteriore soluzione proposta ancora una volta su “Electrical Experimenter” (1918) fu quella di rimorchiare un magnete legato a un cavo, nell’attesa che l’aumento della tensione di quest’ultimo rivelasse che la sua estremità si era attaccata a un sottomarino. L’utilizzo di esplosivi avrebbe poi neutralizzato la minaccia.

Nel contesto della Seconda guerra mondiale un’altra soluzione legata al magnetismo, riportata su “Scientific American” (1940), prevedeva l’impiego combinato di imbarcazioni in ferro – che avrebbero rinforzato il campo magnetico terrestre, rendendo così più visibili eventuali distorsioni dovute alla presenza di sottomarini – e barche in legno dotate di un magnetometro ultrasensibile in grado di individuare tali anomalie e rendere evidente che vi era un mezzo nemico nascosto sottacqua.

Inoltre, si propose un metodo “così semplice [per fermare un sommergibile] che non è ancora stato provato”: puntare una potente luce sul periscopio, accecando il comandante e impedendogli di calcolare la distanza e la velocità della nave che avrebbe dovuto colpire (“Electrical Experimenter”, 1917). L’autore dell’articolo invitava il lettore a diversi esperimenti che provano l’efficacia dell’invenzione, ma mancava di menzionare che l’individuazione di un periscopio nella distesa marina era pressochè impossibile.

Note bibliografiche

-

Friedman, Norman, Fighting the Great war at sea. Strategy, tactics and technology. Barnsley, Pen and Sword Book Ltd, 2014.

-

Halpern, Paul G., A naval history of World War I, Annapolis, United States Naval Institute Press, 1994.

- Mazzini Federico, “Mechanical Vaudeville”. Divulgazione della scienza e trivializzazione della guerra in Popular Science Monthly, in Scienza, tecnica e Grande Guerra. Realtà ed immaginari, ed. by Federico Mazzini, Pisa, Pacini Editore, 2018, pp. 123-151.

- Mazzini, Federico, Una guerra di meraviglie? Realtà ed immaginario tecnologico nelle riviste illustrate della Prima guerra mondiale, Salerno, Orthotes, 2017.

Altre misure immaginarie contro i sommergibili e sottomarini

-

A Submarine DetectorA Submarine Detector

A Submarine DetectorA Submarine Detector -

The Gun-Buoy for Repelling SubmarinesThe Gun-Buoy for Repelling Submarines. It has living quarters for four, telephone connections, periscopes and a rapid-fire gun -all the modern marine conveniences

The Gun-Buoy for Repelling SubmarinesThe Gun-Buoy for Repelling Submarines. It has living quarters for four, telephone connections, periscopes and a rapid-fire gun -all the modern marine conveniences -

Fighting at Night with Searchlight TorpedoesFighting at Night with Searchlight Torpedoes. The torpedoes carry searchlights which are lighted by means of a time fuse when the enemy ships are almost reached

Fighting at Night with Searchlight TorpedoesFighting at Night with Searchlight Torpedoes. The torpedoes carry searchlights which are lighted by means of a time fuse when the enemy ships are almost reached -

Throwing a Torpedo-Proof Wall of Steel Around a ShipThrowing a Torpedo-Proof Wall of Steel Around a Ship. Hundreds of disks, rapidly rotated, are dropped into the water to act as an impenetrable steel wall

Throwing a Torpedo-Proof Wall of Steel Around a ShipThrowing a Torpedo-Proof Wall of Steel Around a Ship. Hundreds of disks, rapidly rotated, are dropped into the water to act as an impenetrable steel wall -

Blinding the SubmarineBlinding the Submarine

Blinding the SubmarineBlinding the Submarine

Sommergibili e sottomarini nel nostro database

-

Que vaut la flotte des soviéts?Que vaut la flotte des soviéts?

Que vaut la flotte des soviéts?Que vaut la flotte des soviéts? -

Un sottomarrino tedesco nido di bagnantiUn sottomarrino tedesco nido di bagnanti

Un sottomarrino tedesco nido di bagnantiUn sottomarrino tedesco nido di bagnanti -

Commemorazione del "Lusitania"Una commovente cerimonia in pieno Oceano. Nel quarto anniversario dell'indimenticabile delitto, dal ponte del sommergibile tedesco "UC97", ora americano, una ghirlanda viene lanciata nel punto in cui fu affondato il "Lusitania"

Commemorazione del "Lusitania"Una commovente cerimonia in pieno Oceano. Nel quarto anniversario dell'indimenticabile delitto, dal ponte del sommergibile tedesco "UC97", ora americano, una ghirlanda viene lanciata nel punto in cui fu affondato il "Lusitania" -

Un auto-torpilleur dirigé par les ondes hertziennesUn auto-torpilleur dirigé par les ondes hertziennes

Un auto-torpilleur dirigé par les ondes hertziennesUn auto-torpilleur dirigé par les ondes hertziennes -

Une torpille sous-marine pilotée au butUne torpille sous-marine pilotée au but

Une torpille sous-marine pilotée au butUne torpille sous-marine pilotée au but