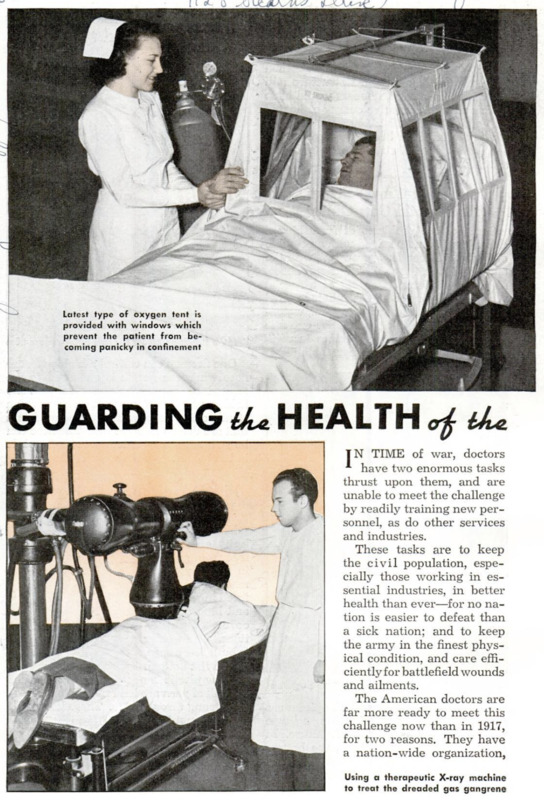

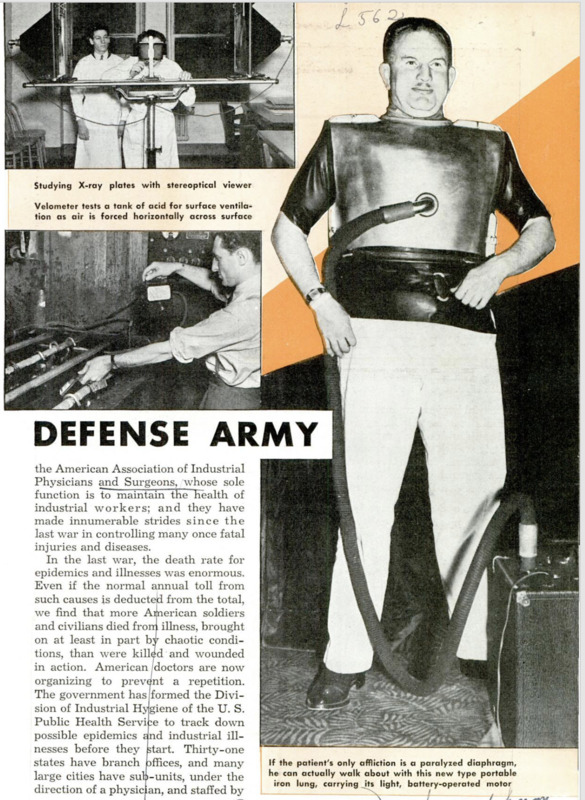

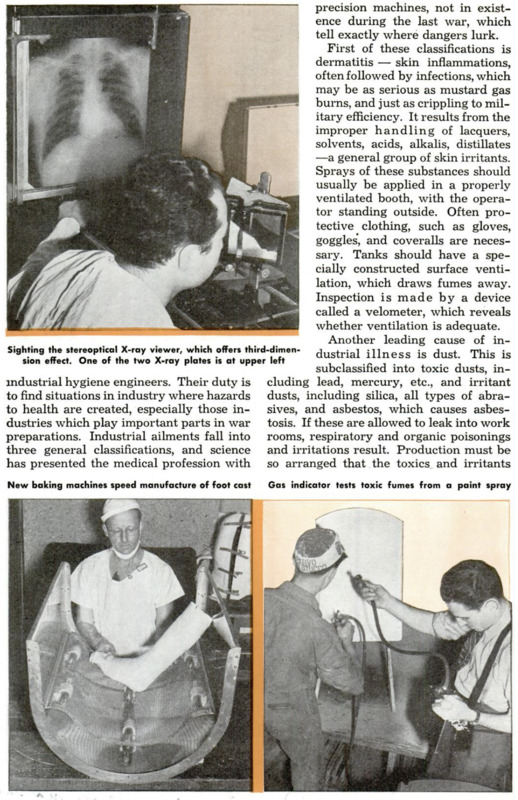

IN TIME of war, doctors have two enormous tasks thrust upon them, and are unable to meet the challenge by readily training new personnel, as do other services and industries. These tasks are to keep the civil population, especially those working in essential industries, in better health than ever - for no nation is easier to defeat than a sick nation; and to keep the army in the finest physical condition, and care efficiently for battlefield wounds and ailments. The American doctors are far more ready to meet this challenge now than in 1917, for two reasons. They have a nation-wide organization, the American Association of Industrial Physicians and Surgeons, whose sole function is to maintain the health of industrial workers; and they have made innumerable strides since the last war in controlling many once fatal injuries and diseases. In the last war, the death rate for epidemics and illnesses was enormous. Even if the normal annual toll from such causes is deducted from the total, we find that more American soldiers and civilians died fronf illness, brought on at least in part by chaotic conditions, than were killed and wounded in action. American [doctors are now organizing to prevént a repetition. The government has|formed the Division of Industrial Hygiene of the U. S. Public Health Servife to track down possible epidemics dnd industrial illnesses before they gtart. Thirty-one states have branch pffices, and many large cities have sub-units, under the direction of a physician, and staffed by industrial hygiene engineers. Their duty is to find situations in industry where hazards to health are created, especially those industries which play important parts in war preparations. Industrial ailments fall into three general classifications, and science has presented the medical profession with precision machines, not in existence during the last war, which tell exactly where dangers lurk. First of these classifications is dermatitis - skin inflammations, often followed by infections, which may be as serious as mustard gas burns, and just as crippling to military efficiency. It results from the improper handling of lacquers, solvents, acids, alkalis, distillates - a general group of skin irritants. Sprays of these substances should usually be applied in a properly ventilated booth, with the operator standing outside. Often protective clothing, such as gloves, goggles, and coveralls are necessary. Tanks should have a specially constructed surface ventilation, which draws fumes away. Inspection is made by a device called a velometer, which reveals whether ventilation is adequate. Another leading cause of industrial illness is dust. This is subclassified into toxic dusts, including lead, mercury, etc., and irritant dusts, including silica, all types of abrasives, and asbestos, which causes asbestosis. If these are allowed to leak into work rooms, respiratory and organic poisonings and irritations result. Production must be so arranged that the toxics and irritants are blocked off from the workers, or otherwise carried away. Some are trapped or carried off by ventilation, others can be controlled by masks, still others by wetting down. Careful dust counts, taken with devices called impingers, will always reveal the presence of these substances in danger zones. A measured sample of air is taken, and the volume of dust is captured in solution. Analysis reveals the kind of dust, and the amount of it in breathable air. If it is excessive, correction of the working conditions must be made as recommended by the industrial hygiene engineers, Third general classification of industrial illness is the toxic solvent, including such substances as benzol, toluol, chlorinated compounds, ete. These are as lethal as military gases, more so, due to their use in enclosed places. Control is effected by methods similar to dust controls - exhaust ventilation, plus periodic check-ups with combustible gas indicators (though the gas in question is not always combustible). War would find the soldiers themselves receiving the finest medical care in history. Countless inventions and great medical progress will take much terror out of battlefield wounds and illnesses contracted through hard living. Today’s knowledge and technique might have done much for the 14,000 who died of wounds in the last war, the 23,000 who died of sickness, and the countless who suffered physical disability. Gas, for instance, was the supreme terror of the World War. Masks have reduced its deadliness, but it is still bad enough. However, doctors are now able to give: prompt, efficient treatment which will save the lives and health of many gas casualties. Principal tool for this job is a new iron lung, that can readily be carried anywhere. Since paralysis of the diaphragm caused many a gas death, this lung is expected to be a mighty boon. It consists of two iron shells, made to fit around the torso, and rendered airtight by large rubber bands around the openings. A hose attaches, and runs to an electric motor, which forces air in and out of the shell at regular intervals, producing artificial respiration. The motor is so light that it can readily be carried by the patient, and is adjustable so that breathing may be fast or slow as exertion requires. Electrically operated, it can obtain power from any light socket, wet or dry batteries, and in an emergency, even from flashlight cells. Another boon to gas casualties is the oxygen tent. Some experiments were made with administering oxygen in high concentrations to gassed soldiers late in the last war, and results were astonishing, but lack of experience and equipment stood in the way. No such lacks exist now. Oxygen tents are plentiful, and so simple is their operation that it can be entrusted to nurses and internes. Other important advances have been made in the X-ray. Barely in its infancy when the last war closed, it no longer is a cumbersome array of sputtering tubes, but a sleek, streamline machine that varies in size from the compactness of a suit case to the bulk of a grand piano. It can reveal every organ in the body simultaneously to the eye or to a photographic plate, or it can confine its inspection to the smallest tissue. An extremely important X-ray development from a military standpoint is the stereoptical viewer for examining negatives. Like the stereoscope granddad used to have, it observes two images simultaneously, permitting three dimensional study of internal organs and the exact location of embedded bullets or shrapnel. Probing for a hidden bullet is no longer necessary. The X-ray has also proved useful in treating many wound complications, especially gas bacillus, called gangrene, which once necessitated so many amputations. But in the Spanish Civil War, another and apparently better method of treating this infection was evolved. Dr. J. Trueta, faced with thousands of casualties, dug up an old medical journal with an article by an American, Dr. Hiram W. Orr, which outlined a technique that had never had sufficient trial to prove its worth. It consisted of cleaning any flesh suspected of infection completely out of a wound, and perhaps a little more to be doubly sure. Then the wound was thoroughly cleansed with soapy water and antiseptic, after which it was packed with sterile gauze, soaked in vaseline. Then a cast was applied, and allowed to remain untouched, even for re-dressing, until the wound was healed. Dr. Trueta treated over 1,000 patients by this method which was practically the reverse of old procedure in every respect. He lost only six, all very advanced cases. Gas bacillus is also responding to the miraculous “sulfa” compounds, so it seems that a still further advance has been made. Indeed, had these drugs - sulfanilimide, sulfapyridine, and sulfathiazol – been known during the World War, dead and crippled lists would have been but a fraction of what they were. Pneumonia alone claimed 83.6 percent of all the 23,000 who died of illness, and eminent doctors, using the sulfas to treat pneumonia, have gone on record with statements that they have the dread disease definitely beaten. Streptococcic infections, dreaded perhaps as much by soldiers as gas bacillus, is also in full retreat before the sulfas. One of the most important things in treating the wounded is promptness; then gangrene, “strep,” and other complications have no chance to start. The airplane is causing many wounds, but it is also rendering them less deadly by providing prompt hospitalization. Germans have been quick to adopt ambulance planes, using great transports with stretchers for eight. In the World War, a wounded soldier went first to the regimental first aid station, then to the first aid station, then to the casualty clearing station, before he could be transferred to a base hospital. Hours elapsed, sometimes days. Ambulance planes cut hours to minutes, days to hours. Recent experiments in nutrition indicate that doctors may be about to banish an ancient army tradition - the lazy private, about whose broad shoulders the sergeant was forever threatening to wrap a gun barrel. Gun barrels could never cure laziness, but hypodermic needles often can, for it seems only a mild case of pellagra - that is, hunger. This seems strange, for American soldiers have always been well fed, but amount of food has little to do with pellagra. It is caused by the lack of certain vitamins and chemicals in the diet. Pellagra specialists, known to the medical profession as “famine fighters”, have taken countless weak, tired, listless persons, and changed them almost overnight into bright, happy, sparkling individuals who wanted nothing more than to tackle a good job.Their techniques, barely in the beginning stage as yet, are being carried into the army. A more vigorous and tireless personnel will surely result. The dental profession, too, has made important advances that will benefit soldiers. Examining physicians are not so insistent upon perfect teeth as they were in 1917. One reason is the improvement of amalgam fillings. Although easier, cheaper, and quicker to install than inlays of gold or porcelain, amalgam tended to shrink and permit additional decay. New materials are said to overcome this difficulty. Another extremely useful dental innovation is the mass production of artificial teeth. An unknown process in 1917, many potentially good soldiers were rejected because they could not readily chew food without expensive artificial dentures. Now, after long and careful study, all teeth have been classified into several groups, and it has been found that a tooth of a certain classification in one person’s mouth is strikingly similar in size and shape to all other teeth of the same classification. Standardized molds can be made, and artificial dentures turned out with mass production economies. Every soldier will have teeth with which to chew his food. Rejections decrease; our reservoir of man power grows. If war does come to us, our soldiers will have the best health and muscles of any soldiers in history. Their morale will not be weakened by poor health. Their wounded will receive prompt, efficient attention, far better than any army has ever received. This is the American doctor’s guarantee.