-

Title (Dublin Core)

-

British military aeroplane

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption (Dublin Core)

-

War Progress in Flying

-

extracted text (Extract Text)

-

THE way aeroplanes were flown

before the war seems almost

ridiculous now, after men have

really learned how to fly as the result of

war's -exigencies. The old way made

them an easy prey for anti-aircraft guns

and for attack-

ing machines.

When it be-

came necessary °

to dart out of

the range of a

high-angle bat-

tery, which

had suddenly

revealed its

presence with

bursting shrap-

nel, or when

only a quick

maneuver

could prevent

a hostile

machine from

blocking the

way home, the

old-fashioned,

steady, level

flyer and slow

climber

proved a very

death-trap.

Looping-the-

loop, caper-cutting, all the acrobatic

performances that attend exhibition

flying became normal evolutions. Only

excess power for a sudden burst of speed

and climbing would avail in a perilous

moment.

A fast-climbing machine, which also

has the virtue of exhibiting great lifting

power in the thin air of high altitudes,

naturally vaults into the air easily in a

difficult start on rough ground. In a

critical landing—when, for instance, the

ground, which, from above seems invit-

ingly smooth, turns out to be alarmingly

rough—the fast-climbing machine can

easily stop its swift descent and leap

lightly over an obstacle. By reducing

his power while the machine is flying at

a steep angle, the pilot may even touch

the ground at a very low speed.

Salvation Lies in High Power

A machine thus able to deal with rough

ground is most stable in rough air. An

aviator fears

what he calls a

“hole in the

air—a pocket

formed by a

downwardly-

twisting cur-

rent. Into such

a hole he drops

in a sickening

way because

his wings no

longer have an

upward blast

to support

them. Hesaves

himself, not by

trying to climb

out—a useless

proceeding —

but by steering

downward,

thus increasing

his speed and

likewise the

pressure be-

neath his

wings. ‘“To go up, one must sometimes

steer up, at other times steer down,”

Wilbur Wright told me in his little

insignificant bicycle shop in Dayton,

Ohio, in 1905, in discussing the 16w-

powered Witeht machine.

Evidently the aviator needed power

to combat these difficulties. This he

obtained by resorting to surplus-powered

and reserve-powered machines. There

would seem to be no distinction between

the two terms, but the difference is this:

the surplus-powered machine has a

motor which is more than able to make

it fly and the excess power of which is

constantly used for normal flight; the

reserve-powered machine uses its excess

only in an emergency.

In the surplus-powered acroplane,

“steering down to keep up” is not a

praiseworthy maneuver. A pilot cannot

possibly know how far the “hole” or

local descending current extends and

whether he will not plunge into the

ground before he gets out of it. But

with the reserve-powered machine, it is

otherwise. When it steers up, it goes

up—always; and what is still more

important, it goes up instantly. The

words “goes up” do not apply literally.

They should read, “keeps up.” A

heavy machine cannot go up instantly

on account of its inertia, but it can as

instantly increase its lift as it can turn

on full power and put its surfaces at a

steeper angle. To steer down in order

to keep up was relatively a slow proceed-

ing, because even with the aid of gravity

inertia cannot instantly be overcome.

But with reserve power there is no need

to overcome inertia, and the remedy

can be applied at once.

With these explanations in mind, we

understand why Europeans speak as

they do of some dead officer who “lost

his life because he attempted to imitate

champions on high-powered machines

with a weak machine.”

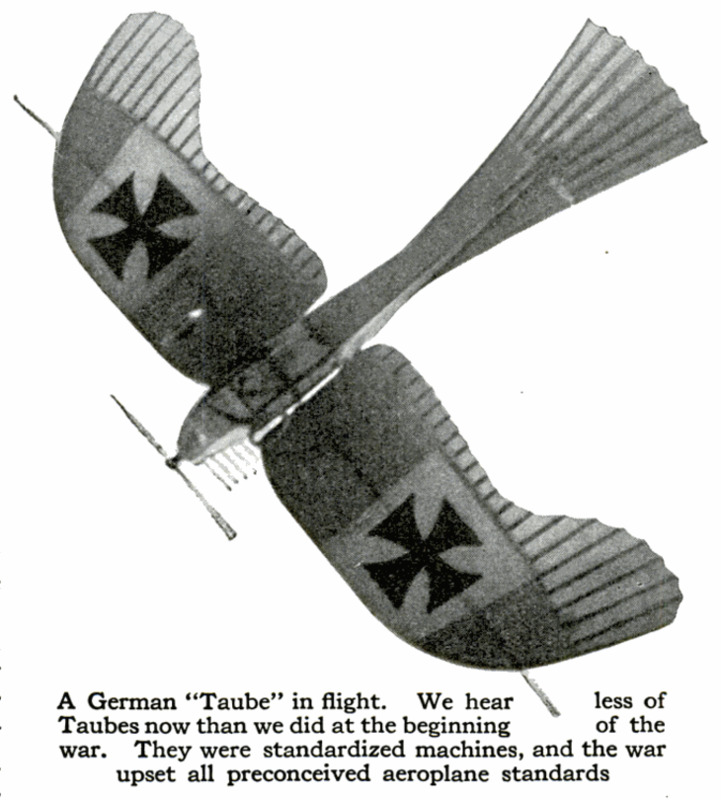

The Germans had drawn somewhat

too hasty conclusions as to the best type

of a military aeroplane and had standard-

ized it. The French simply enlisted all

their current sporting types for army

use, types which were 5 0 in long-

range scouting, demanding, as it does,

only reliability and sturdiness in normal

flight, for which the Germans had

provided at. the war's beginning. But

the French machines were better for

aerial fighting, which has about as much

to do with steady, normal flying as a

free-for-all fight with walking in a

procession. The new art of flying had

to be learned in aerial duels, just as a

boy is taught to swim by the simple

process of throwing him overboard.

Daily encounters in the sky prove

conclusively enough that flying has been

as thoroughly mastered as horseback

riding. In neither can any attention be

paid to handling the machine. There

are too many other very important

matters to think about. The machine

must respond to any subconscious action

of its rider as obediently as a cavalry

horse, so that its guidance becomes as

much a matter of subconscious action

as that of a warhorse. Accounts of air-

duels read, in fact, as though fighting

acroplanes were under better control

than cavalry horses. To place a shot at

close range in these wild swoops, with-

out being hit, can be compared only

with fighting a saber-duel while jumping

hurdles. The fastest French and British

machines were found to be the most

formidable fighters. Hence they were

imitated (and fatally bettered) by the

Germans and Austrians.

And Yel, the Aeroplane Is

Unchanged

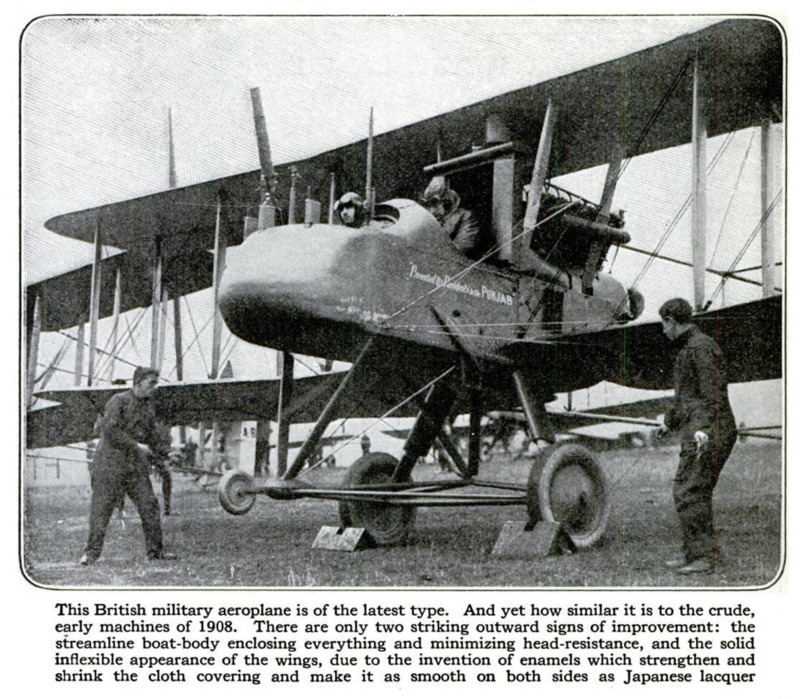

It is surprising how little the general

appearance of the aeroplane has changed

during its entire history, in spite of its

marvelous development. Only the

automatically stable types, distinguished

by their backwardly-turned wings and

upturned tips are an exception. But the

aeroplane is such a simple device (and

has been found best in its simplest forms)

that the phenomenon is easily explained.

There are only two striking outward

signs of improvement: the streamline

boat-body, enclosing everything and

minimizing head-resistance, and the

solid, inflexible appearance of the wings,

due to the invention of enamels which

strengthen and shrink the cloth covering

and make it as smooth on both sides as

Japanese lacquer.

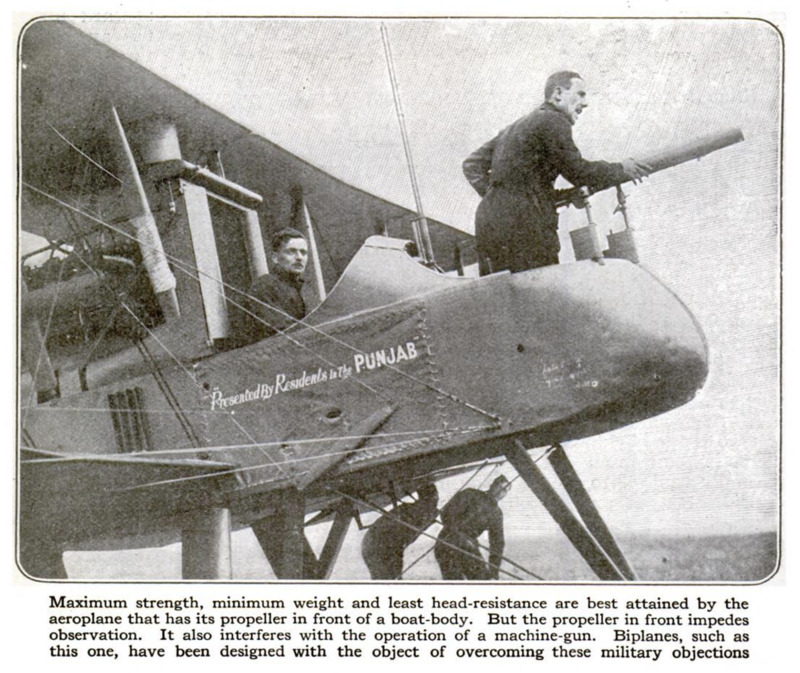

Maximum strength, minimum weight

and least head-resistance are best

attained by the aeroplane that has its

propeller in front of a boat-body.

‘Thanks to the tractor-screw the biplane

has developed as much speed as the

monoplane. Itis even preferred, since its

greater surface gives more lift in emer-

gencies. Unobstructed vision in front is

often so desirable that the propeller is

sometimes placed behind the surfaces

and the boat-body shortened, in spite

of the increased head-resistance and

decreased strength of the design with

the rudders carried by poles. A beautiful

solution of the problem of free vision is

obtained in large passenger-carrying

machines, with the long bodies of which

rudders are integrally combined, two

tractor-screws and two separate motors

being mounted on both sides of the main

body. It is then essential to enclose the

motors in separate bodies. In the big

German battleplanes, the motor bodies

are long and carry the rudders. Even

such’ designs waste-a-certain amount of

power, because a catamaran has always

less speed than a single hoat. But

multiple bodies and division of load

across the span of the planes is the only

method by which large aeroplanes are

enabled to carry many passengers and

to exhibit that strength which it has

taxed all the ingenuity of the scientific

engineer to obtain even in the smaller

machine.

Has the Big Aeroplane Come

to Stay?

Mammoth aeroplanes are at present a

spectacular development, especially in

America. But it would be premature to

include them in a seriously critical

review of the acroplane of to-day. In

the main, they have not yet justified

themselves, although some of the big

water machines of Curtiss, are said to be

in frequent use. But there are no

accounts of their performances under

very critical air conditions, when their

relative lack of strength would be a very

serious matter, judging from the ex-

periences of similar smaller machines.

‘What recommended them is not economy

of performance (because they carry

relatively less per square foot of surface

than smaller water machines) but the

improved facilities offered for navigation,

comfort for long trips, and the advantage

that one pilot can transport many

passengers. They are also required,

whenever a great radius of action is

demanded, which can be obtained with

aeroplanes only by cutting down the

passenger list and carrying more fuel

instead. In a small machine, this would

mean amputating the alighting gear. |

The difficulty of starting and alighting |

with a mammoth plane is serious. - The

impact of the heavy mass is too much

for its strength, especially for the landing

wheels, which have to be made very

bulky and clumsy, consequently wasting

power in air-resistance. Transformed

into a flying boat the mammoth machine |

becomes more practical, because the hull |

partakes of all the naval advantages

that follow with increased size. Strains

to which they are subject from gusts

must be formidable. But no technical

accounts of their behavior in the air have

been published.

Air-fighting is fully as romantic

as ever were the deeds of Homer's

heroes or Cooper's Indians; for this is

the day of personal prowess in air-fight-

ing. We need not dwell solely. on the

exploits of such German supermen as

Immelmann and Boeke (each with

a record of at least fifteen victories).

Neither superiority of numbers nor of

machines cuts much of a figure if it is

matched against a certain mysterious

personal equation, which cannot as yet

be completely analyzed. It may be

safe to say that rapid, masterful marks-

manship plays in it no small part. It

would be indeed a rare coincidence if

this ability were likewise found combined

with exceptional talents (like Pégoud's)

for managing an aeroplane. If that be

the case it is obvious that a fighter and

flyer in one person must be more formid-

able than the co-operation of a mere

flyer and a mere fighter. We need only

imagine two cavalrymen on the same

horse (assuming that they could be

accommodated together as perfectly as

two flyers on a machine) of whom one

wields only the lance and the other

manipulates the bridle. How should

they communicate their respective inten-

tions in fractions of a second?

But this holds good only in regard to

small powerful racing machines which

fight wasp-like at close range.

-

Contributor (Dublin Core)

-

Carl Diestbach (writer)

-

Language (Dublin Core)

-

eng

-

Date Issued (Dublin Core)

-

1916-10

-

pages (Bibliographic Ontology)

-

523-527

-

Rights (Dublin Core)

-

Public Domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by (Dublin Core)

-

Filippo Valle

-

Alberto Bordignon (Supervisor)

Popular Science Monthly, v. 89, n. 4, 1916

Popular Science Monthly, v. 89, n. 4, 1916