-

Titolo

-

Dropping Death from the Skies

-

Article Title and/or Image Caption

-

Dropping Death from the Skies. The bomb dropper and his murderous winged weapons which deal quick and ghastly death

-

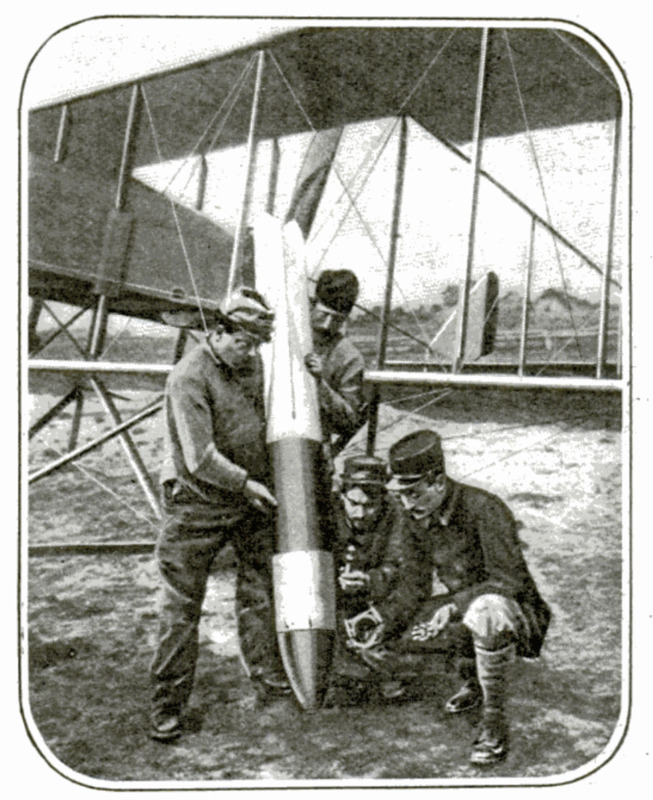

Caption 1: Modern "fletched" airplane bomb. Note streamline form, size, and weight, as shown

-

Caption 2: A wonderful photograph taken from a French airplane while bombing a German factory in Lorraine. Seven bombs may be seen in the air, all released together by the same machine

-

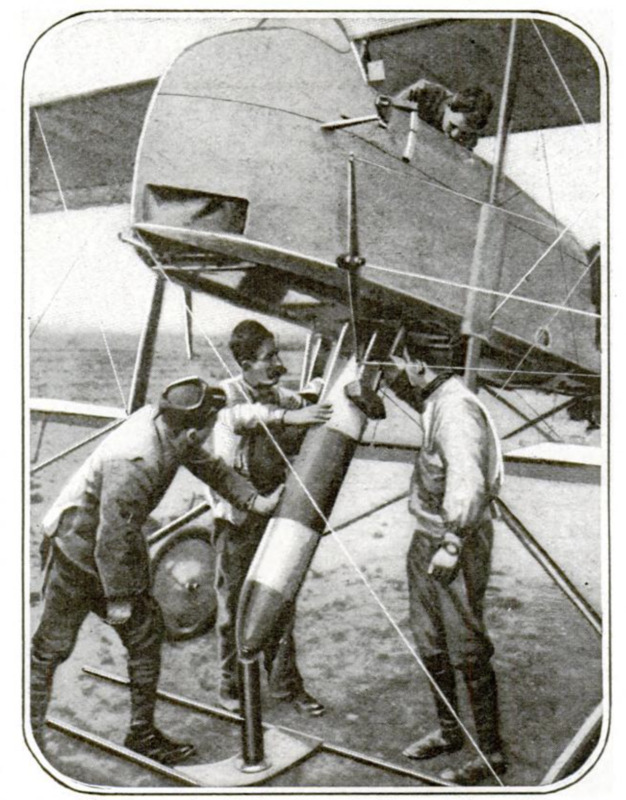

Caption 3: Slipping a bomb into an airplane. The tail is

being inserted smoothly into the discharge tube

-

extracted text

-

HARDLY had the airplane been

adopted asa military weapon some

four years before the outbreak of

the great European war, when the pos-

sibilities of bomb dropping began to be

considered. To the general public at

least, it seemed easy to wipe out a fort,

to demolish a bridge, or to blow up a

battleship by the simple expedient of

dropping on it a hundred pounds of high

explosive. Engineers knew better. Long

before the first

Zeppelin flew over

London, it was

pointed out that

it was hard to hit

a target on the

ground from an

elevated platform

moving at fifty

miles an hour and

more, because al-

lowances had to

be made for

deflecting winds

for the horizontal

motion acquired

by the bomb from

the airplane. To

hit a target the

plane's height

and speed over

ground had to be

known with almost

impossible ac-

curacy, and even

if known, an in-

finitesimal hesita-

tion in releasing the bomb would spoil the

aim. A truly super-human sense of time

was demanded. The difficulty, only

vastly exaggerated, is the same as that

which a hunter experiences in hitting

running or flying game by aiming ahead

of the target. Whether the target moves

swiftly or the gun and the missile have a

fast motion of their own, aiming ahead

causes all the trouble.

On the whole, the public has been more

far-seeing than military engineers. It

reckoned with moral effects in its own

unreasoning way rather than with phy-

sical principles. Bomb-dropping has be-

come an indispensable mode of attack.

‘The civilians of all the warring powers

protest against it in vain. Germans de-

nounce the “baby killing” tactics of the

Allied aviators as hotly as England de-

nounces the German slaughter of defense-

less woman and children. Whether or

not fortified places

are bombed, civil-

iansinvariably suf-

fer. A dozen

bombs may be

aimed at a muni-

tions factory.

One, perhaps, finds

its mark. The

rest are scattered

over a residential

quarter with an

effect too ghastly

to be described.

Aim at a powder

mill and you hit a

hospital.

As the war pro-

gressed, bombing

became ‘more ac-

curate, although

the misses still far

outnumbered the

hits. The reason

for this increased

accuracy is re-

vealed in the truly

remarkable photographs of French bombs

which we publish herewith and which

have been permitted to reach this coun-

try by a lenient censor.

The bombs pictured have been called

“aerial torpedoes.” They do bear an

outward resemblance to the naval tor-

pedo. For all that, the designation is

incorrect. The internal construction

bears little resemblance to that of a naval

torpedo. The bomb shown is provided

with tail planes to make it fly straight—

a tail which has the same effect on the

bomb as the tail feathers have on an

arrow. In addition there is a ‘pro-

peller” to sensitize the percussion fuse

during the bomb’s fall.

Particular attention is directed to the

extraordinary photograph which shows

seven bombs flying through the air after

having been released nearly simultane-

ously. They do not drop. They liter-

ally rush through the air like naval

torpedoes, thereby to a certain extent

justifying their alias. Released from a

machine which is traveling at a speed of

ninety miles an hour, they necessarily

have, for a time, the forward motion of

that machine and actually travel hori-

zontally. Realizing all this, their dc-

signers gave them an ideal streamline

form. In the picture only the lowest

bombs have begun to turn downward

visibly and to drop vertically. The up-

permost one is seen gliding like an air-

plane itself in spite of its great weight,

in spite of its comparatively small surface

and in spite of the fact that it has only a

belly in place of wings. The moment

bombs drop from their tubes (one-third as

slowly as they are swept ahead by the

plane) they are swung by momentum and

air pressure on |

their tail planes

into a nearly |

horizontal po-

sition. In that |

position their

shape encoun- |

ters practically

no resistance

from ahead

but a great re-

sistance in the

direction of

gravity, not

only because in

trying to fall

they must

cleave the air |

with their big

broad sides,

but chiefly be-

cause in drop-

ping they are

nowopposedby

the inertia of

the air encoun- |

tered in falling,

and, in addi-

tion, the much |

greateramount

of air encoun-

tered in mov-

ing ahead. As |

long as momentum continues, falling is

greatly retarded, and, with practically no

head resistance, it is bound to continue

indefinitely. But as soon as actual falling

begins, the head dips a little, aided by the

tail planes. In this position the fall itself

will preserve and increase the horizontal

speed, just as in coasting down hill in a

sleigh. If the total surface of a correctly

designed bomb were not so extremely

small in proportion to its weight, it

would seemingly never reach the ground.

Balloonists sometimes threw empty

bottles from their baskets. They mar-

velled at the crazy antics performed by

the bottles and the long time they took

in reaching the ground. It was the ap-

proximation of streamline form that de-

layed the bottles.

Bombing is like torpedoing. Bombs

have assumed the shape of torpedoes

not to prolong their fall, a thing in it-

self ratlier unfavorable, but because the

lower winds have practically no influence

over a torpedo.

Guided by its

tail, the tor-

pedo-shaped

bomb simply

turns its sharp

nose against

the wind and

cleaves it

without deflec-

tion.

That is why

bomb-drop-

ping is more

accurate than

it was at the

outbreak of the

war. More-

over,bombsare

dropped on the

shotgun or

blunderbuss

principle. In

other words,

they are re-

leased a half a

dozen or more

at atime. One

at least will

find its mark.

By releasing

bombs in quick

succession,

errors in judging altitude and speed are

readily corrected, because the bombs

scatter principally along a line parallel

with the path of the machine.

-

Autore secondario

-

Carl Dientsbach (writer)

-

Kadel and Herbert (photos)

-

Lingua

-

eng

-

Data di rilascio

-

1918-04

-

pagine

-

518-520

-

Diritti

-

Public Domain (Google digitized)

-

Archived by

-

Filippo Valle

-

Alberto Bordignon (Supervisor)